Red Scare facts for kids

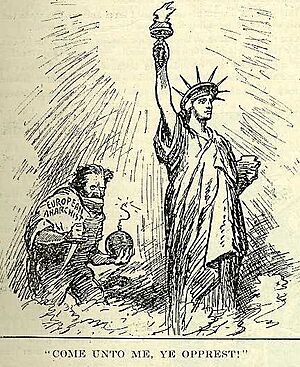

A Red Scare is when many people in a country become very afraid that communism, anarchism, or other left-leaning ideas might take over. This fear is often spread through propaganda, which is information used to influence how people think.

The term "Red Scare" is most often used for two times in United States history. The First Red Scare happened right after World War I. People were worried about American workers, anarchist ideas, and other radical political changes. The Second Red Scare happened after World War II. During this time, many worried that communists from inside or outside the U.S. were secretly trying to spy on or overthrow the government and society. The name "Red Scare" comes from the red flag, which is a common symbol for communism.

Contents

First Red Scare (1917–1920)

The first Red Scare started after the Russian Revolution of 1917. This revolution led to a wave of communist movements in Europe and other parts of the world. In the U.S., these were very patriotic years because of World War I. However, there was also a lot of unrest from anarchists and other left-wing groups.

Political expert Murray B. Levin said the Red Scare was "a nationwide anti-radical hysteria." People were very afraid that a communist revolution like the one in Russia would happen in America. They worried it would change everything about American life. Newspapers made these fears worse, especially against immigrants. Many new ideas, like anarchism, were becoming popular among recent European immigrants as ways to solve poverty.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), also called the Wobblies, supported many worker strikes in 1916 and 1917. These strikes happened in important industries like steel, shipbuilding, and coal mining, which were vital for the war. After World War I ended, the number of strikes grew even more in 1919. There were over 3,600 strikes, including steel workers, railroad workers, and even the Boston police.

The news often said these strikes were "radical threats to American society." They claimed "left-wing, foreign agents" were behind them. Supporters of the IWW said the news unfairly called their fair labor strikes "crimes against society" or "plots to establish communism." But opponents saw these strikes as part of the IWW's radical goals to unite all workers and end capitalism.

In 1917, during World War I, Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917. This law aimed to stop any information about national defense from harming the U.S. or helping its enemies. The government used this act to stop anything that "urged treason" from being mailed. Because of this, 74 newspapers were not allowed to be sent through the mail.

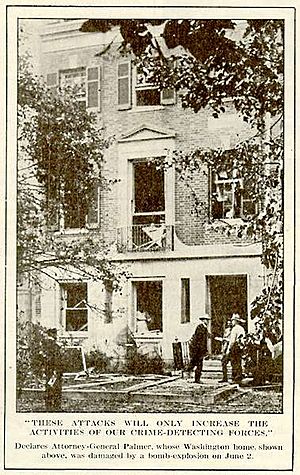

In April 1919, authorities found a plan to mail 36 bombs to important people in U.S. politics and business. These included J. P. Morgan Jr., John D. Rockefeller, and U.S. Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer. On June 2, 1919, eight bombs exploded at the same time in eight different cities. One bomb badly damaged Attorney General Palmer's home in Washington, D.C.. The explosion killed the bomber, who was likely an Italian-American radical from Philadelphia.

After these bombings, Palmer ordered the U.S. Justice Department to start the Palmer Raids (1919–21). During these raids, 249 Russian immigrants were deported on a ship called the "Soviet Ark." Palmer also helped create the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Federal agents arrested over 5,000 citizens and searched homes without respecting their constitutional rights.

Even before the bombings, in 1918, President Woodrow Wilson had pushed Congress to pass the Sedition Act of 1918. This law aimed to protect wartime spirit by deporting people thought to be politically undesirable. Law professor David D. Cole said that President Wilson's government often targeted foreign radicals. They deported them for their speech or groups they belonged to, without really telling the difference between terrorists and people who just had different ideas. President Wilson used the Sedition Act to limit free speech by making it a crime to say things that seemed disloyal to the U.S. government.

At first, newspapers praised the raids. The Washington Post said there was "no time to waste on hairsplitting over [the] infringement of liberty." The New York Times said the injuries to those arrested were "souvenirs of the new attitude of aggressiveness." However, twelve well-known lawyers, including future Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, criticized the Palmer Raids. They published a report showing that Palmer's actions broke several parts of the U.S. Constitution.

Palmer then warned that a left-wing revolution would start on May 1, 1920, which is May Day. When it did not happen, he was made fun of and lost a lot of trust. Also, out of thousands of immigrants arrested and deported, fewer than 600 deportations had real evidence to support them. In July 1920, Palmer's chance to become president failed.

On September 2, 1920, Wall Street was bombed near Federal Hall National Memorial and the JP Morgan Bank. Even though anarchists and communists were suspected, no one was ever charged for the bombing. It killed 38 people and injured 141.

In 1919–20, several states passed "criminal syndicalism" laws. These laws made it illegal to support violence to make social changes. They also limited free speech. These laws led to aggressive police investigations, jailing, and deportation of people suspected of being communist or left-wing. The Red Scare did not really tell the difference between communism, anarchism, socialism, or social democracy. This harsh crackdown on certain ideas led to many Supreme Court cases about free speech. In the case of Schenk v. United States, the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 were found to be constitutional.

Second Red Scare (1947–1957)

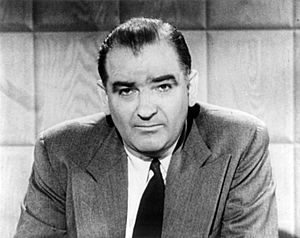

The second Red Scare happened after World War II (1939–1945). It is often called "McCarthyism" after Senator Joseph McCarthy, who was its most famous supporter. McCarthyism happened at the same time as a growing fear of communist spying. This fear grew because of rising tensions in the Cold War. Events like the Soviet control of Eastern Europe, the Berlin Blockade (1948–49), the end of the Chinese Civil War, and the start of the Korean War all added to this fear. Also, some high-ranking U.S. government officials admitted to spying for the Soviet Union.

Why people feared communism

Events in the late 1940s and early 1950s made Americans very worried. These included the trial of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg (1953), the trial of Alger Hiss, the "Iron Curtain" separating Eastern Europe, and the Soviet Union's first nuclear weapon test in 1949. These events made people afraid that the Soviet Union would drop nuclear bombs on the United States. They also feared the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA).

In Canada, a 1946 investigation looked into spying after secret documents about weapons were given to the Soviets by a spy group.

At the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), former CPUSA members and Soviet spies, Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers, said that Soviet spies and communist supporters had secretly entered the U.S. government. Other U.S. citizens also admitted to spying, even if they could no longer be charged. In 1949, the fear of communism and American traitors grew when the Chinese Communists won the Chinese Civil War. They created Communist China, and later helped North Korea in the Korean War against the U.S. ally South Korea.

Some events during the Red Scare were also due to a power struggle. This was between FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Hoover helped investigate CIA members who had "leftist" backgrounds.

Historian Richard Powers points out two main types of anti-communism then. One was "liberal anti-communism," which believed that open debate would show communists were disloyal. The other was "countersubversive anti-communism," which thought communists needed to be exposed and punished. Sometimes, countersubversives even accused liberals of being as bad as communists.

Much evidence of Soviet spying existed, according to Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan. He said the Venona project had "overwhelming proof of the activities of Soviet spy networks in America." However, Moynihan argued that because these sources were kept secret for so long, people fought without knowing the full truth. He believed McCarthy's extreme views turned the discussion about communist spies into a civil rights issue instead of a security one.

History of the Second Red Scare

Early years

By the 1930s, communism seemed like an appealing economic ideology, especially to labor leaders and thinkers. By 1939, the CPUSA had about 50,000 members. In 1940, after World War II began in Europe, the U.S. Congress passed the Alien Registration Act (also called the Smith Act). This law made it a crime to support or teach the idea of overthrowing the U.S. government by force. It also required all foreign nationals to register with the government. While mainly used against communists, the Smith Act was also used against other groups, like the German-American Bund.

After Hitler and Stalin signed a non-aggression pact in 1939, the communist party in the U.S. became anti-war. People saw them as working with the Nazis, so they were treated with more hostility. However, in 1941, when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, the CPUSA changed its stance to pro-war. They opposed labor strikes in weapons factories and supported the U.S. war effort against the Axis Powers. The chairman, Earl Browder, even used the slogan "Communism is Twentieth-Century Americanism." In contrast, the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party opposed U.S. involvement in the war and supported labor strikes. Because of this, their leaders were convicted under the Smith Act.

Increasing tension

In March 1947, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9835. This order created the "Federal Employees Loyalty Program." It set up review boards to check the "Americanism" of government workers. All federal employees had to take an oath of loyalty. This led to over 2,700 firings and 12,000 resignations between 1947 and 1956. It also inspired similar loyalty laws in several states.

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was created during Truman's time as president. Republicans had accused Truman's government of disloyalty. HUAC and Senator Joseph McCarthy's committees investigated "American communists" (real and suspected). They looked into their roles in spying, propaganda, and efforts to help the Soviet Union. These investigations showed how much the Soviet spy network had entered the federal government. They also helped launch the political careers of Richard Nixon, Robert F. Kennedy, and Joseph McCarthy. HUAC was very interested in investigating people in the Hollywood entertainment industry. They questioned actors, writers, and producers. Those who cooperated could keep working, but those who refused were blacklisted.

Senator Joseph McCarthy made the fear of communists in the U.S. even worse. He claimed communist spies were everywhere and that he was America's only hope. He used this fear to gain more power. In 1950, McCarthy spoke to the Senate, naming 81 separate cases and making accusations against suspected communists. He gave little or no proof, but this led the Senate to call for a full investigation.

Senator McCarran introduced the McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950. This law changed many things to limit civil liberties in the name of security. President Truman called the act a "mockery of the Bill of Rights" and a "long step toward totalitarianism." He believed it limited freedom of opinion. He vetoed the act, but Congress overrode his veto. Much of the bill was later removed.

The creation of the People's Republic of China in 1949 and the start of the Korean War in 1950 led to more suspicion of Asian Americans. Especially those of Chinese or Korean descent were suspected of supporting communism. Some American politicians worried that Chinese students educated in America would take their knowledge back to "Red China." Laws like the China Aid Act of 1950 and the Refugee Relief Act of 1953 helped Chinese students who wanted to stay in the U.S. However, even naturalized Chinese immigrants continued to face doubts about their loyalty. This meant that Chinese (and other Asian) students were expected to support the American government but avoid getting involved in politics.

The Second Red Scare deeply changed American society. It led to movies like My Son John (1952), about parents suspecting their son is a spy. Many stories had themes of American society being secretly taken over or destroyed by "un-American" ideas. Even a baseball team, the Cincinnati Reds, temporarily changed their name to the "Cincinnati Redlegs." They wanted to avoid the bad meaning of being called "Reds" (communists).

In 1954, Congress passed the Communist Control Act of 1954. This law stopped members of the communist party in America from holding positions in labor unions and other worker organizations.

Wind down

Historian John Earl Haynes, who studied the Venona project decryptions, said that Joseph McCarthy's efforts to use anti-communism as a political weapon actually hurt anti-communist efforts. He argued that it threatened the unity against communism that existed after the war. By 1950, the "shockingly high level" of Soviet spies during WWII had mostly gone away. Liberal anti-communists like Edward Shils and Daniel Patrick Moynihan disliked McCarthyism. Moynihan argued that McCarthy's extreme actions distracted from the "real (but limited) extent of Soviet espionage in America." In 1950, President Harry S. Truman called Joseph McCarthy "the greatest asset the Kremlin has."

In 1954, Senator Joseph McCarthy accused the army, including war heroes. This made him lose trust with the American public. The Army–McCarthy hearings were held in the summer of 1954. McCarthy was officially criticized by his fellow members of Congress, and the hearings he led came to an end. After the Senate officially criticized McCarthy, his political power greatly decreased. Much of the tension about a possible communist takeover then died down.

From 1955 to 1959, the Supreme Court made several decisions that limited how the government could enforce its anti-communist policies. These included limiting the federal loyalty program to only those with access to sensitive information. They also allowed people accused of crimes to face those who accused them. The court reduced the power of congressional investigation committees and weakened the Smith Act.

In the 1957 case Yates v. United States and the 1961 case Scales v. United States, the Supreme Court limited Congress's ability to get around the First Amendment (freedom of speech). In 1967, in the case United States v. Robel, the Supreme Court ruled that banning communists from working in the defense industry was unconstitutional.

In 1995, the U.S. government released details of the Venona Project. This, along with the opening of Soviet archives, showed strong proof of Soviet spying and influence in the U.S. from 1940 to 1980. Over 300 American communists, including government officials and scientists who helped develop the atom bomb, were found to have been involved in spying.

New Red Scare

According to The New York Times, China's growing military and economic power has led to a "New Red Scare" in the United States. Both Democrats and Republicans have shown "Anti-China sentiment." The Economist says this new Red Scare has caused the American and Chinese governments to "increasingly view Chinese students with suspicion" on American college campuses.

A group called the "Committee on the Present Danger: China" (CPDC) was formed on March 25, 2019. This group has been criticized for trying to bring back Red Scare politics in the U.S. David Skidmore, writing for The Diplomat, called it another example of "adolescent hysteria" in U.S. diplomacy. He said such "fevered crusades" have led to some of the most costly mistakes in American foreign policy.

|

See also

In Spanish: Temor rojo para niños

In Spanish: Temor rojo para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |