23 Wall Street facts for kids

|

23 Wall Street

|

|

|

U.S. Historic district

Contributing property |

|

23 Wall Street in 2007

|

|

| Location | 23 Wall Street Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Built | 1913 |

| Architect | Trowbridge & Livingston |

| Architectural style | Neoclassical |

| Part of | Wall Street Historic District (ID07000063) |

| NRHP reference No. | 72000874 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | June 19, 1972 |

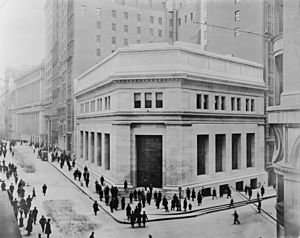

23 Wall Street is an important office building in the Financial District of Manhattan, New York City. It stands at the corner of Wall Street and Broad Street. Designed by Trowbridge & Livingston, this four-story building was built between 1913 and 1914. It was originally the main office for J.P. Morgan & Co., a very powerful bank.

The building has a simple, classical look with plain limestone walls and simple windows. Its ground floor is very tall, with two more stories above it. Even though it never had the Morgan name on its outside, everyone knew it as the "House of Morgan." Inside, the main banking room had a high, decorated ceiling and later, a huge crystal chandelier. The basement held vaults and equipment, while upper floors had offices.

23 Wall Street replaced an older building, the Drexel Building. It was damaged in the Wall Street bombing in 1920. However, J.P. Morgan & Co. chose to leave the shrapnel marks on the building as a sign of defiance. In 1957, it was connected to the building next door, 15 Broad Street. They served as the bank's headquarters until 1988. Since 2008, 23 Wall Street has mostly been empty. It is a protected landmark in New York City and is part of the Wall Street Historic District.

Contents

Location and Surroundings

23 Wall Street is located in the busy Financial District of Manhattan. It sits at the southeast corner of Broad Street and Wall Street. The building's plot of land is about 113 feet long on Broad Street and 157 feet long on Wall Street. It is right next to 15 Broad Street.

Other famous buildings nearby include the New York Stock Exchange Building and Federal Hall National Memorial (an old government building). The Broad Street subway station has entrances right outside 23 Wall Street.

Before 23 Wall Street, the site held the Drexel Building. This was the headquarters for Drexel, Morgan & Co., the bank that later became J.P. Morgan & Co. The Drexel Building was built in 1873 and was known for being one of New York City's first fireproof buildings.

Building Design

23 Wall Street was designed by the architects Trowbridge & Livingston. It was built in a classical style. Many parts of the building's design were chosen by J. P. Morgan himself, who led the bank. Unlike the tall skyscrapers around it, 23 Wall Street was built with only four main floors above ground.

The building has an unusual, irregular shape. It has a special angled corner at its main entrance, where Wall Street and Broad Street meet. This corner was designed to make the intersection look like a public square. The building's facade (its front and sides) rises about 85 feet from the street.

Outside Look

The outside of 23 Wall Street is made of pink Tennessee marble. J. P. Morgan wanted the marble to be the same as the marble in his home library. The walls are plain, with simple windows that are set deep into the stone. You can still see marks on the facade from the Wall Street bombing in 1920.

The first floor looks very tall, like a grand main floor. Above it is a shorter second floor, and then a third floor without windows. The fourth floor is set back, so you can't see it from the street. A decorative ledge, called a cornice, runs between the second and third stories.

The main entrance is at the angled corner of Wall and Broad Streets. A few steps lead up to a large, recessed doorway. The door is made of bronze and glass. J. P. Morgan wanted sculptures on the sides of the entrance, but he passed away before they were added. No company name was ever placed on the outside, but the building became famous anyway. The stone above the doorway was one of the largest ever brought to New York City at the time.

The rest of the Wall Street and Broad Street sides look similar. They have tall rectangular windows on the ground floor.

Inside Features

Basement and Foundations

The building's foundations go deep into the ground, about 65 feet. They were built strong enough to support a much taller building, even one with 30 stories.

The basement held a large, three-story vault. This vault was described as one of the biggest of its kind when the building was finished. Its walls were very thick, made of steel and concrete. The vault door was a huge, round steel door that weighed 50 tons. The rest of the basement was used for the building's heating and cooling systems, and for storage.

Main Floor

The entire ground floor was a huge, open space with very high ceilings. It was designed to use every bit of space. Just inside the main entrance was a small waiting area with stairs and an elevator to the upper floors.

The main banking room was about 15,000 square feet and had a 30-foot-high ceiling with a pattern of gold hexagons and circles. In the middle of the ceiling was a shallow dome. In the 1960s, a huge crystal chandelier with 1,900 pieces was added under the dome.

In the center of the room was a main lobby. It had a mosaic floor and was surrounded by a screen made of pink marble and bronze. This screen had carvings inspired by Greek myths and the story of Hiawatha. Zodiac symbols were placed in the center of the floor, as they were a symbol for J. P. Morgan's club.

The outer walls of the ground floor had tall marble panels. Along the lobby's sides were conference rooms and offices for the bank's partners. The foreign exchange department and waiting rooms were also on this floor. A painting of J. P. Morgan hung on one wall.

Upper Floors

The building's structure is made of a steel frame, but the steel beams are hidden inside the walls. J. P. Morgan wanted them out of sight. The upper floors are actually hung from large steel supports.

The second floor held the private offices of the bank's partners and their assistants. J. P. Morgan's own office was right above the main entrance. Each office was designed to the partner's liking and often had fireplaces and oak wood decorations.

The third floor had private dining rooms, a kitchen, and bedrooms for executives. The fourth floor contained rooms for staff and a roof garden that looked out over the New York Stock Exchange. This roof garden could be covered by an awning and used for meetings in winter. It also had a small barber shop. When the building next door, 15 Broad Street, was turned into apartments, the roof of 23 Wall Street became a large garden and pool for the residents.

Building History

J.P. Morgan and Company became a very important bank in the United States in the late 1800s. By the early 1900s, their old building, the Drexel Building, was too small. J.P. Morgan wanted a bigger, grander headquarters. The land at Wall and Broad Streets was considered one of the most valuable spots in New York City.

Construction of the New Building

In 1912, J.P. Morgan & Co. bought the Drexel Building. They also bought the Mechanics and Metals National Bank building next door. They decided to tear down both old buildings and build a new headquarters.

In early 1913, Trowbridge & Livingston were chosen as the architects. J. P. Morgan passed away shortly after the plans were submitted. Demolition of the old buildings began in May 1913. The site was cleared by July, and foundation work started. The new building's facade was mostly finished by June 1914.

23 Wall Street officially opened on November 11, 1914. The total cost to build it was over $5 million. Even though the building had no name on its outside, everyone quickly recognized it as the home of J.P. Morgan & Co.

Early 1900s Events

After J.P. Morgan Jr. helped fund the Allies in World War I, he received threats. Detectives were placed around 23 Wall Street for protection. The building was designed with thick walls and a wire net over the roof to protect against attacks.

On September 16, 1920, the Wall Street bombing happened right outside the building. Thirty-eight people died, and hundreds were hurt. Most of the damage was outside, but shrapnel from the bomb entered the building, causing significant damage inside. The outside of the building only got small marks from the shrapnel. J.P. Morgan & Company decided not to repair these marks. They wanted to show defiance to those who committed the crime. These marks were later called "a badge of honor."

In the late 1920s, a new skyscraper, 15 Broad Street, was built around 23 Wall Street. J.P. Morgan & Co. leased some space in this new building because 23 Wall Street was still not big enough.

Mid to Late 1900s

J.P. Morgan & Co. continued to grow and needed even more space. In 1955, they bought 15 Broad Street. The two buildings were connected in 1957.

In 1959, J.P. Morgan & Co. merged with another company to become Morgan Guaranty Trust. They wanted to have their main office in one place. A big renovation started in 1962 to combine 23 Wall Street and 15 Broad Street into one headquarters. Morgan Guaranty officially moved into both buildings in February 1964.

In 1985, Morgan Guaranty announced they would move to a new, larger building at 60 Wall Street. They moved out of 23 Wall Street in 1988. In the 1990s, 23 Wall Street was updated to be used for training and conferences.

In the late 1990s, the New York Stock Exchange thought about building a new trading floor next to or inside 23 Wall Street. This plan would have kept 23 Wall Street as a visitor center. After the September 11 attacks in 2001, the NYSE still wanted to build there, but they eventually decided against it.

21st Century Changes

In 2003, 23 Wall Street and 15 Broad Street were sold. The new owners planned to turn them into apartments. The roof of 23 Wall Street was made into a garden and pool for the residents of 15 Broad Street. The inside of 23 Wall Street was meant to be used for shops.

In 2008, 23 Wall Street was sold again to a group of companies. The building has been mostly empty since then, even though brokers tried to find a luxury store to rent the space. In 2015, there was a plan for an entertainment center, but local residents did not like the idea.

In 2016, an artist planned a temporary art show in the empty building, but it was canceled. Later that year, a real estate company tried to buy 23 Wall Street, but the sale was not completed. In 2020, the real estate company decided to lease the building for 99 years instead of buying it.

Building's Impact

Landmark Status

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission named the outside of 23 Wall Street a city landmark on December 21, 1965. It was one of the first buildings in Manhattan to receive this protection. Later, in 1972, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 2007, it was also recognized as an important part of the Wall Street Historic District.

In Media

23 Wall Street has appeared in many movies and photographs. Soon after it was built, it was featured in the famous photograph Wall Street (1915) by Paul Strand. This photo was taken from Federal Hall.

The building has also been used for filming movies. For example, it was used in the 2012 film The Dark Knight Rises, where it was shown as the fictional Gotham City Stock Exchange. Part of the 2014 film Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles was also filmed at 23 Wall Street.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: 23 Wall Street para niños

In Spanish: 23 Wall Street para niños