Racial segregation in Atlanta facts for kids

Racial segregation in Atlanta means separating people based on their race. After slavery ended in 1865, Atlanta went through many changes. At first, people of different races lived and worked closer together. But then, Jim Crow laws and the Atlanta Race Riot in 1906 led to strict separation. This meant black and white people had to live in different areas and often use different businesses.

Later, in the 1950s, a process called "blockbusting" caused more changes in neighborhoods. From the late 1960s, Atlanta slowly started to become more integrated, meaning people of all races could live and work together more freely. Even today, some studies show Atlanta is still one of the most segregated cities in the U.S.

Life After the Civil War

After the Civil War ended, many people moved to Atlanta, including formerly enslaved people looking for work. The number of black residents in Fulton County grew a lot. Many new arrivals didn't have much, and groups like the American Missionary Association helped them.

Housing Challenges and Segregation

The war destroyed many homes in Atlanta, and with so many new people arriving, there weren't enough places to live. Rent was very expensive. Because of this, many black families ended up living in areas on the edge of the city. These places, like Jenningstown and Summerhill, often had poor housing that was still expensive. These areas were also low-lying and sometimes flooded, leading to health problems.

The Fifth Ward, which had many black residents before the war, became less populated by black families. New black neighborhoods like Mechanicsville also started to grow in the 1870s.

Jim Crow Laws and Their Impact

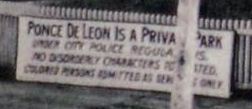

After the Atlanta Race Riot in 1906, many Jim Crow laws were quickly put in place. These laws forced black and white people to be separate and treated black people unfairly. Often, facilities for black people were much worse, or there were no facilities for them at all. For example, all public parks became "whites-only." A private park called Joyland opened in 1921 for black residents.

In 1910, a city rule said that restaurants had to serve only one race. This hurt black restaurant owners who used to serve both black and white customers. Also in 1910, Atlanta's streetcars were segregated. Black riders had to sit in the back. If there weren't enough seats for white riders, black riders in the front had to give up their seats.

In 1913, the city even created official boundaries for where white and black people could live. By 1920, black-owned hair salons were not allowed to serve white women or children.

Beyond these laws, black people had to follow strict racial rules. This meant they had to show respect to all white people, even those with less social standing. While black people had to call white people "sir," they rarely received the same respect. Breaking these rules could lead to serious trouble, making daily life a constant reminder of unfairness.

Gone with the Wind Premiere

On December 15, 1939, Atlanta hosted the big premiere of Gone with the Wind. This famous movie was based on a book by Atlanta writer Margaret Mitchell. Movie stars like Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh were there. The premiere was at Loew's Grand Theatre, and a huge crowd of 300,000 people filled the streets, even though it was a very cold night.

Black Stars Excluded from Premiere

Two black actresses from the movie, Hattie McDaniel (who played Mammy) and Butterfly McQueen (who played Prissy), were not allowed to attend the premiere. They were also left out of the souvenir program and movie ads in the South. The movie's director tried to get Hattie McDaniel to come, but the studio told him not to. Clark Gable was so angry he threatened not to go, but McDaniel convinced him to attend. She did get to attend the Hollywood premiere a few weeks later.

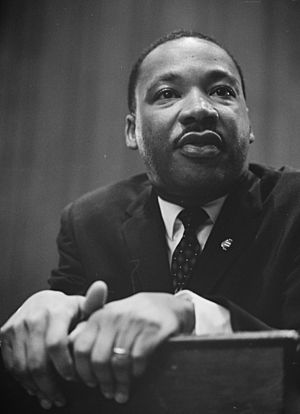

Martin Luther King Jr.'s Controversial Role

Martin Luther King Jr. sang at the gala as part of a children's choir from his father's church. The children wore outfits that many black people found humiliating. Some leaders in the black community tried to stop Rev. King Sr. from participating in the whites-only event, and he faced strong criticism.

Neighborhood Changes and "Blockbusting"

In the late 1950s, laws that forced people to live in certain areas were removed. However, some white neighborhoods used threats and pressure to stop black families from buying homes there. But by the late 1950s, these efforts didn't work. A practice called blockbusting began. This is when real estate agents would scare white homeowners into selling their homes cheaply by telling them black families were moving into the neighborhood. Then, these agents would sell the homes to black families at higher prices.

This led many white families to sell their homes in neighborhoods like Adamsville and Edgewood. In 1962, the city tried to stop this by putting up road barriers in Cascade Heights. This event became known as "Atlanta's Berlin Wall."

However, these efforts to stop neighborhood changes also failed. New neighborhoods with black homeowners grew, which helped with the housing shortage for African Americans. Many western and southern Atlanta neighborhoods became mostly black. Between 1950 and 1970, the number of areas that were at least 90 percent black tripled. Neighborhoods like East Lake and Cascade Heights changed almost completely from white to black. From 1960 to 1970, the percentage of black people in the city grew from 38 to 51 percent. At the same time, 60,000 white residents left the city.

This movement of white residents to the suburbs, known as "White flight", and the building of suburban malls, caused downtown Atlanta to slowly lose its role as a main shopping area. However, it continued to be a center for government, hotels, and conventions.

1956 Sugar Bowl

In January 1956, Bobby Grier became the first black player to play in the Sugar Bowl. He was also the first black player to compete in a bowl game in the Deep South. Grier's team, the Pittsburgh Panthers, was scheduled to play against the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets.

Georgia's Governor Marvin Griffin asked Georgia Tech not to play in this racially mixed game. However, news media criticized Griffin, and Georgia Tech students protested at his home. Despite the governor's objections, Georgia Tech played the game. Grier said he mostly had good memories of the experience, including support from his teammates and letters from around the world.

Civil Rights Movement in Atlanta

After the important U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education, which said that separate schools were not equal, racial tensions in Atlanta sometimes led to violence. For example, in 1958, a Jewish temple on Peachtree Street was bombed. Many believed that Jewish people supported the Civil Rights Movement.

In the 1960s, Atlanta was a key center for the Civil Rights Movement. Martin Luther King Jr. and students from Atlanta's historically black colleges played big roles. On October 19, 1960, a sit-in at lunch counters in several Atlanta department stores led to the arrest of Dr. King and several students. This event got attention from national news and from presidential candidate John F. Kennedy.

Even with this incident, Atlanta's leaders tried to present the city as "the city too busy to hate." While Atlanta mostly avoided major conflicts, some smaller race riots did happen in 1965 and 1968.

Ending Segregation

Ending segregation in public places happened step by step. Buses and trolleybuses were desegregated in 1959. Restaurants at Rich's department store followed in 1961. Movie theaters became desegregated in 1962-63.

In 1961, Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. was one of the few white Southern mayors to support desegregating his city's public schools. At first, only a few schools were integrated, but real desegregation happened in stages from 1961 to 1973.

Segregation Today

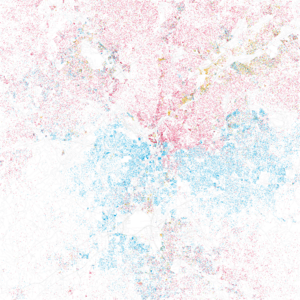

Measuring how much segregation still exists can be tricky. Generally, the wider Atlanta metro area is more integrated than the city of Atlanta itself. However, among cities with many black residents, Atlanta ranks low in terms of how many people live in truly mixed neighborhoods.

Within metro Atlanta, segregation is often more noticeable in the older, more urban counties like DeKalb and Fulton. Atlanta's black population is still mainly in older city neighborhoods. This can make it harder to reach new job opportunities that are growing in the suburbs.

Racial stereotypes and fears can also affect where people choose to live. Some studies show that white residents might resist integration due to negative stereotypes, while black residents might resist due to past experiences of discrimination. Also, segregation is often linked to economic differences. In some areas, where most residents are black, poverty rates are much higher than in areas where most residents are white.

However, metro Atlanta has become more integrated over time. The way we measure segregation for black residents has shown a decrease from 1980 to 2000, meaning more mixing. On the other hand, segregation for Hispanic residents has increased in Atlanta, which had one of the largest increases among U.S. cities.

Even with these changes, some parts of the city are still mostly black or white:

- About 60 percent of the city's area is made up of mostly black neighborhoods. For example, Northwest, Southwest, and Southeast Atlanta are 92 percent black.

- Some areas are mostly white, like Buckhead and Northeast Atlanta neighborhoods such as Virginia-Highland and Morningside/Lenox Park. These areas are, on average, 80% white.

Recently, a complaint was filed with the Department of Education. A mother learned that her child's principal was separating children based on their skin color.

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |