1906 Atlanta race riot facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1906 Atlanta race riot |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Nadir of American race relations | |

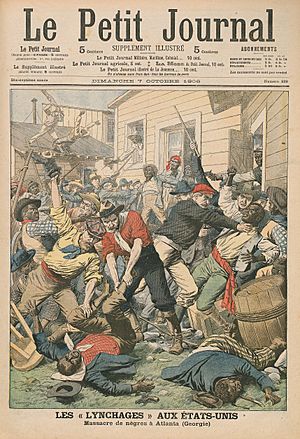

The cover of French magazine Le Petit Journal in October, 1906, depicting the Atlanta race riot

|

|

| Location | Atlanta, Georgia |

| Date | September 22–24, 1906 |

| Target | African Americans |

| Deaths | 25+ African Americans, 2 white Americans |

|

Non-fatal injuries

|

90+ African Americans, 10 white Americans |

| Perpetrators | White mobs, and Fulton county police. |

The Atlanta Race Riot of 1906 was a series of violent attacks. White mobs attacked African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia. These attacks started on the evening of September 22, 1906. They continued through September 24.

Newspapers around the world reported on these events. For example, the French Le Petit Journal wrote about the "massacre of Negroes in Atlanta." The Scottish Aberdeen Press & Journal used the headline "Race Riots in Georgia." The London Evening Standard reported on "Anti-Negro Riots."

The exact number of people who died is not fully known. Officially, at least 25 African Americans and two white people died. Some unofficial reports said that 10 to 100 black Americans were killed.

The main reason for the violence was newspaper stories. These stories claimed that black men had attacked four white women. However, deeper reasons included growing racial tension. Atlanta was changing fast, and people were competing for jobs, homes, and political power.

The violence stopped only after Governor Joseph M. Terrell called in the Georgia National Guard. Some African Americans said that the Atlanta Police Department and some Guardsmen also took part in the attacks. For many years, local histories written by white people did not mention this event. It was not until 2006, on its 100th anniversary, that the event was publicly recognized. The next year, the Atlanta riot became part of Georgia's public school history lessons.

Contents

Understanding the Atlanta Race Riot

Atlanta's Growth and Changes

After the American Civil War ended, during the Reconstruction era, there was much violence against black people in the South. White people reacted strongly to black people being freed from slavery. They also reacted to black people gaining the right to vote and hold political power. The idea of former slaves becoming equals was a threat to some white people.

Atlanta grew very quickly after the war. Many people moved there for work, especially from the 1880s onward. It became a major "rail hub" (a central point for trains) in the South. This led to a huge increase in Atlanta's population. The African-American population grew from 9,000 in 1880 to 35,000 in 1900. The city's total population jumped from 89,000 in 1900 to 150,000 in 1910.

With more people, there was more demand for homes and jobs. This made race relations in Atlanta very tense. White people made Jim Crow segregation stricter. This meant black and white people were kept separate in neighborhoods and on public transportation.

African-American Progress

During Reconstruction, freed slaves and their children gained the right to vote. White people became more fearful and angry about black people using their political power. African Americans also started successful businesses. Some even became part of an elite group, different from working-class black people. Some white people did not like this success.

One successful black businessman was Alonzo Herndon. He owned a large, fancy barber shop that served important white men. This new success led to more competition for jobs between black and white people. It also highlighted differences between social classes. The police and fire departments were only white. Most city and county government jobs were also only for white people.

In 1877, state laws made it harder for black people to vote. They used things like poll taxes (money paid to vote) and special record-keeping rules. Still, many black people could vote. In the 1906 election for governor, both main candidates, M. Hoke Smith and Clark Howell, used racial tensions in their campaigns. Smith openly promised to take away black people's right to vote in Georgia. Howell also wanted to keep black people out of politics.

Smith used to publish the Atlanta Journal. Howell was the editor of the Atlanta Constitution. Both candidates used their newspapers to stir up white voters. They spread fears that white people might lose control of society. These papers also attacked bars and saloons run by or visited by black citizens.

Key Events of the Riot

The Clansman and Rising Tensions

The play The Clansman by Thomas Dixon, Jr. was performed in Atlanta. Historians believe this play helped cause the 1906 race riot. The play showed white mobs attacking African-American communities. When the play opened in Savannah, police and soldiers were on high alert. They were present on every streetcar going to the theater. In Macon, authorities asked for the play to be banned, and it was.

Newspaper Reports and Attacks

On Saturday afternoon, September 22, 1906, Atlanta newspapers reported four attacks on white women. They claimed black men were responsible. After these reports, groups of white men and boys gathered. They started to beat, stab, and shoot black people. They pulled black people off streetcars or attacked them on the street. This began in the Five Points area downtown.

Newspaper extra editions were printed. By midnight, an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 white men and boys were in the downtown streets. They roamed around, looking for black people to attack. By 10 PM, three black people had been killed. Many more were in the hospital, and at least five of them later died. Three of the injured were women.

Governor Joseph M. Terrell called out eight companies of soldiers and one artillery unit. By 2:30 AM, about 25 to 30 black people were reported dead. Many more were injured. The trolley lines were closed before midnight to stop people from moving around. This was hoped to discourage the mobs and protect African-American neighborhoods. However, white people were still going into these neighborhoods. They attacked people in their homes or forced them outside.

Alonzo Herndon's barbershop was one of the first places the white mob attacked. Its valuable furnishings were destroyed. Black men were killed on the steps of the US Post Office. One man was chased and killed inside the Marion Hotel. That night, a large mob attacked Decatur Street. This street was a center for black restaurants and saloons. The mob destroyed businesses and attacked any black people they saw. Mobs then moved to Peters Street and nearby areas, causing more damage. Heavy rain from 3 AM to 5 AM helped calm the rioting.

The next day, Sunday, the events were widely reported. Violence against black people continued. Le Petit Journal in Paris reported, "Black men and women were thrown from trolley-cars, assaulted with clubs and pelted with stones." By Monday, The New York Times reported that at least 25 to 30 black men and women were killed. About 90 were injured. One white man was reported killed, and about 10 were injured.

Many black people were killed or injured on the streets and in their shops. The militia (soldiers) arrived in the city center by 1 AM. But most were not armed or organized until 6 AM. More soldiers were then placed in the business district. Small gangs continued sporadic violence in other parts of the city late into the night. On Sunday, hundreds of black people left Atlanta by train and other ways. They sought safety elsewhere.

Attempts at Defense

On Sunday, a group of African Americans met in the Brownsville community. This area was south of downtown and near Clark University. They had armed themselves for defense. Fulton County police found out about the meeting and raided it. An officer was killed in a shootout that followed. Three militia companies were sent to Brownsville. They arrested and disarmed about 250 black people, including university professors.

The New York Times asked Mayor James G. Woodward about what was done to prevent the riot. He replied that the best way to prevent a riot depends on its cause. He said, "As long as the black brutes assault our white women, just so long will they be unceremoniously dealt with." He had tried to calm the mobs on Saturday night but was mostly ignored.

Aftermath of the Riot

Grand Jury Findings

On September 28, The New York Times reported on the findings of the Fulton County Grand Jury. The Grand Jury believed that the way Atlanta's afternoon newspapers reported crime news had greatly influenced the mob. They also thought that the newspaper The Atlanta News had encouraged people to act outside the law. The Grand Jury strongly condemned the sensational reporting of the afternoon papers.

Final Number of Deaths

The exact number of African Americans killed in the riot is still debated. At least two dozen African Americans were believed to have died. Two white people were confirmed dead. One was a woman who died from a heart attack after seeing mobs outside her home.

Discussions and Changes

On the Monday and Tuesday after the riot, important white citizens met. The mayor was among them. They discussed the events and how to prevent more violence. Leaders from the black community also joined these meetings. This helped start a tradition of communication between the groups. However, for many decades, the massacre was ignored in the white community. It was left out of official city histories.

The riot had a big impact on the African-American economy. Businesses suffered from property losses, damage, and disruption. Some businesses had to close. The black community made big social changes. Businesses moved away from mixed areas. Black people settled in neighborhoods that were mostly black. This was partly due to unfair housing practices that lasted until the 1960s. Many black businesses moved from the city center to the east. There, the successful black business district known as "Sweet Auburn" soon grew.

Many African Americans disagreed with Booker T. Washington's approach. He taught at Tuskegee Institute and believed in working with white society. Instead, many black Americans felt they needed to be stronger in protecting their communities. They also wanted to advance their race. Some black Americans changed their minds about needing to defend themselves with weapons.

W. E. B. Du Bois, a Harvard-educated scholar, taught at Atlanta University. He supported leadership by the "Talented Tenth" (a term for educated black leaders). After the riot, he bought a shotgun. He said that if a white mob had come onto his campus, he would have used it to defend himself. Later, Du Bois argued that organized political violence by black Americans was not wise. However, he always believed in the right and duty of self-defense when black people faced real threats.

In 1906, Hoke Smith was elected governor. He kept his campaign promise by suggesting a new law in August 1907. This law required a literacy test for voting. This test was used unfairly by white officials. It took away the right to vote from most black people and many poor white people. The law also included "grandfather clauses." These clauses made sure white people could still vote, even if they couldn't read or didn't own enough property. The Democratic Party also created a "white primary." This was another way to keep black people from voting. These changes became part of the state's constitution in 1908. They effectively stopped most black people from voting. Racial segregation was already law. Both these systems, under Jim Crow, largely continued until the late 1960s.

After World War I, Atlanta tried to improve race relations. In 1919, the Commission on Interracial Cooperation was created. This group later became the Southern Regional Council. However, most city institutions still did not allow African Americans. For example, no African-American police officers were hired until 1948, after World War II.

Remembering the Riot

The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot was not included in local histories for many decades. It was largely forgotten. In 2006, on its 100th anniversary, the city and citizen groups remembered the event. They held discussions, forums, and other events. These included walking tours, public art, and memorial services. Many articles and three new books were also published. The next year, the riot became part of Georgia's social studies curriculum for public schools.

The Riot in Other Media

- The film When Blacks Succeed: The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot (2006) was made by Norman and Clarissa Myrick Harris. It won awards.

- Thornwell Jacobs wrote a novel called The Law of the White Circle. It is set during the 1906 massacre. It includes a foreword by historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage. It also has extra materials by Paul Stephen Hudson and Walter White, who was a long-time president of the NAACP.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Disturbios raciales de Atlanta de 1906 para niños

In Spanish: Disturbios raciales de Atlanta de 1906 para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |