Racial segregation in the United States Armed Forces facts for kids

Racial segregation in the U.S. Armed Forces meant separating white and non-white American troops. It also included banning people of color from serving or limiting them to support jobs. Since the American Revolution, different parts of the Armed Forces had different rules about segregation.

Even though Executive Order 9981 officially ended segregation in 1948, some forms of it continued. This lasted until after the Korean War. For example, the U.S. government stopped black soldiers from being stationed at the U.S. base in Keflavík, Iceland. This was due to a request from the Icelandic government and continued into the 1970s and 1980s.

Contents

- Early Days: The American Revolution

- United States Army: A Long Road to Equality

- War of 1812: Needing More Soldiers

- Civil War: Fighting for Freedom

- Buffalo Soldiers: Guardians of the West

- Spanish-American War: Breaking Barriers

- Philippine Scouts: Skilled Soldiers

- World War I: Segregation and Bravery

- World War II: Continued Segregation and Change

- 1950s Desegregation: A Slow Process

- The Vietnam War: A New Kind of Fight

- United States Air Force: Taking to the Skies

- United States Navy: Life at Sea

- United States Marine Corps: A Long History of Exclusion

Early Days: The American Revolution

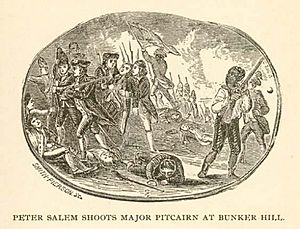

During the American Revolution, people had different ideas about black soldiers joining the Continental Army. Some black soldiers had already fought in colonial militias. But many white people worried that armed black soldiers could be a threat.

Even though black soldiers like Crispus Attucks were famous for their bravery, some white people still thought black people were not good enough to serve. Because of fears about slave rebellions, George Washington first ordered that no black person could join the army.

However, this rule didn't last long. The army needed more soldiers. Also, the British enemies were allowing black soldiers to fight. So, Washington changed his mind. Enslaved people were promised freedom if they joined the army. This promise was sometimes kept by their owners.

For example, enslaved black soldiers in the 1st Rhode Island Regiment were freed after the war. This was the first military unit made entirely of non-white soldiers. In other units, black and white soldiers fought together. One historian even said the military back then was more integrated than it would be for many years, until the Korean War.

United States Army: A Long Road to Equality

After 1792, the Army generally did not allow black men to join. This rule mostly stayed in place until the American Civil War.

War of 1812: Needing More Soldiers

About one million black people lived in the U.S. when the War of 1812 started. At first, black people were not widely recruited. But when America faced big threats from British soldiers, things changed. In 1814, 2,000 free black soldiers were trained in New York. They were paid the same as white soldiers.

However, most black soldiers joined the U.S. Navy or even the British Royal Navy to gain their freedom.

Civil War: Fighting for Freedom

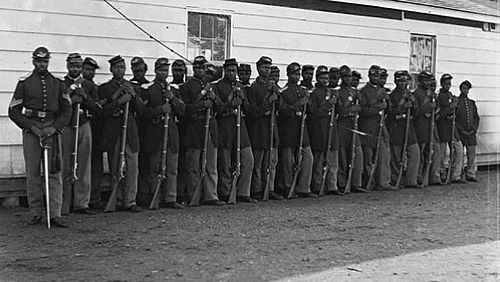

The American Civil War saw many African American men join the Union Army. About 186,000 African American men formed 163 units. Both free African Americans and those who had escaped slavery also joined the Union Navy.

On the Confederate side, black people, both free and enslaved, were mostly used for labor. There was a big debate among Southerners about whether to arm them. A Confederate militia unit of free black soldiers from New Orleans was formed, but the Confederacy refused their service. In 1865, a law was passed to allow black soldiers, but few were recruited.

Asian and Pacific Islander troops also served with African Americans in the United States Colored Troops. Some even served with white troops. Native Americans fought in their own tribal groups on both sides of the war.

Buffalo Soldiers: Guardians of the West

The Buffalo Soldiers were created in 1866. They were the first all-black regiments in the regular U.S. Army during peacetime. Their job was to protect settlements in the western frontier. This meant fighting native people and bandits. Buffalo Soldiers were paid $13 a month and had very low rates of soldiers leaving the army without permission.

Spanish-American War: Breaking Barriers

During the Spanish–American War (1898), the Illinois 8th Infantry National Guard made history. This all-African-American unit was led by black officers in combat.

Philippine Scouts: Skilled Soldiers

In 1901, a law allowed the recruitment of Filipino people into the Army. Fifty-two companies, all from the same regions, were formed. The Philippine Scouts were known as very skilled soldiers with low desertion rates. Their regiment lasted until the end of World War II.

World War I: Segregation and Bravery

African-American Soldiers

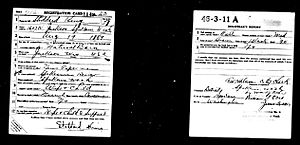

The American military was completely segregated for African Americans during World War I. Despite opposition from some politicians, the Selective Service Act of 1917 was passed. This law required all male citizens over 21 to register for the draft.

About 290,527 black Americans registered. Black soldiers were drafted at a much higher rate than white soldiers, especially in the South. Even though black people were only 10% of the U.S. population, they made up about 13% of those drafted. Draft officials were told to tear off the bottom left corner of forms filled out by black registrants. This marked them for segregated units.

At the start of World War I, there were four all-black regiments. Two combat units were formed: the 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions. However, after the Houston Riot in 1917, most black soldiers were given jobs like building roads or unloading ships.

About 350,000 African Americans served in Europe. One combat unit, the 369th Infantry "Hell Fighters from Harlem," was awarded the Croix de Guerre by the French for their bravery. The 370th Infantry was called "The Black Devils" by the Germans. It was the only American unit with black officers.

Hispanic-American Soldiers

The 65th Infantry Regiment, formed during World War I, was the last segregated U.S. military unit. It was mainly made up of soldiers from Puerto Rico, Latin America, and Spain.

Asian-American Soldiers

Asian Americans fought in integrated units during World War I. Non-citizens were even offered citizenship after the war because of their service.

World War II: Continued Segregation and Change

During World War II, the United States Army created new segregated units and kept old ones.

African-American Soldiers

When the U.S. entered World War II, the Army was still segregated. Even though African American soldiers had served in every previous American war, they faced exclusion and discrimination. In 1939, only 3,640 black soldiers were in the army, led by white officers.

Groups like the NAACP pushed for more black participation and an end to discrimination. This led to changes in the Selective Service Act of 1940. Military leaders started to address the issue in 1943, but segregation remained official policy until 1948.

President Roosevelt set a limit that black soldiers should make up 9% of the military. However, the Army never even reached this number. Most black soldiers were not sent overseas because foreign governments often requested their exclusion.

The United States Army Nurse Corps was mostly white until 1941. After pressure from black nurse groups and Eleanor Roosevelt, black nurses were allowed to join. A limit of 48 black nurses was set, and they were segregated from white nurses and soldiers. More black nurses joined over time. They cared for black soldiers and served in various parts of the world.

Japanese-American Soldiers

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, men of Japanese descent were seen as enemy aliens. They were not allowed in the U.S. draft. Also, the government forced most Japanese Americans on the West Coast to move to internment camps inland.

It wasn't until 1944 that a fighting unit of Japanese-American Nisei (American-born) men was formed. Japanese Americans could only join the Army, not the Navy, Marines, or Air Corps. The 442nd Infantry Regiment, mostly made of Japanese Americans, fought bravely in Europe.

Chinese-American Soldiers

Unlike Japanese Americans, 75% of Chinese American soldiers served in non-segregated units. About 13,000 Chinese Americans served in World War II. Two units, the 407th Air Service Squadron and the 987th Signal Company, were all Chinese American and based in the China Burma India Theater.

1950s Desegregation: A Slow Process

In 1948, President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981. This order aimed to end segregation in the armed forces. The Army was very resistant to this. They only fully cooperated when a shortage of troops in the Korean War forced black soldiers to serve alongside white soldiers.

Even though military units were officially desegregated after the Korean War in 1954, racial tensions continued. This caused problems within units, especially during the Vietnam War. These internal conflicts made military leaders want to improve racial relationships in the Army.

The Vietnam War: A New Kind of Fight

During the Vietnam War, black soldiers faced two battles. One was against discrimination within the army and in civilian life. The other was on the battlefield. African American soldiers were more likely to be drafted and had higher casualty rates. They were also often not recognized in popular culture.

However, despite some discrimination, the Vietnam War was the first American war where the U.S. military was fully integrated. At one point, African Americans made up 23% of combat troops, even though they were only 16.3% of the draft population. This increase in combat roles was a big change from earlier wars, where black men were often seen as unfit for combat.

United States Air Force: Taking to the Skies

When the United States Army Air Service, which later became the Air Force, was formed in 1918, only white soldiers were allowed.

During World War II, the Army Air Service needed more people. They started recruiting black men to train as pilots in the Tuskegee Airmen program. Black men and women also worked in administrative and support jobs. Asian-American men and women (except Japanese-Americans) were recruited into integrated units during World War II.

Tuskegee Airmen: Breaking Barriers in the Air

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African American military pilots in the U.S. armed forces. During World War II, African Americans in southern states still lived under Jim Crow laws. The American military was racially segregated.

Despite strong opposition from many politicians and the public, the Tuskegee Airmen began their training in October 1940. They faced racial discrimination both inside and outside the army. But they trained and flew with great skill and courage. All black military pilots in the U.S. trained at Tuskegee.

The Tuskegee Airmen, also known as the 99th Fighter Squadron, started preparing to go overseas in April 1943. White pilots were sent overseas after less training, sometimes as little as five weeks. But African American pilots received much more training in things like radio communication, radar, and combat.

The Tuskegee 332nd Fighter Group was the only unit that saw combat. They were sent overseas as part of Operation Torch. They later fought in Sicily and Italy. They were very successful as bomber escorts in Europe.

War of 1812: A Need for Sailors

At the start of the War of 1812, official U.S. policy did not allow black sailors. However, the Navy needed more people, so they had to accept any able-bodied man. About 15-20% of naval manpower during the War of 1812 was black. On some privateer ships, more than half the crew was black.

Life on crowded ships often created a sense of teamwork and respect based on how well someone performed. Many enslaved black Americans joined the British Royal Navy because the British promised them freedom.

Commodore Isaac Chauncey wrote that he had fifty black sailors on his ship and called them "excellent seamen." He said, "I have yet to learn that the color of skin... can affect a man's qualifications and usefulness." Black Americans like Charles Ball and Harry Jones played important roles in the war effort, despite prejudice.

1839: Limiting Black Sailors

From the end of the War of 1812 until the Civil War, there isn't much information about the number of black men in the Navy. However, a letter from Commodore Lewis Warrington in 1839 shows that about 12% of new recruits were black.

Because of complaints, the Navy decided to limit the number of black sailors to no more than 5% of the total. No enslaved person was allowed to join.

Unlike the U.S. Army, the U.S. Navy was integrated during the Civil War. While earlier rules limited black sailors to 5% of the force, during the American Civil War, black participation grew to 20% of the Union Navy's total force. Almost 18,000 men of African descent and 11 women served in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War. Their rank and pay depended on whether they were free or formerly enslaved.

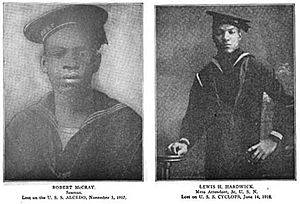

World War I: Specific Roles

On Navy ships, black sailors often worked as mess attendants (serving food), firemen, or coal passers (moving coal to fuel the ships). They could also be promoted to petty officers. Navy ships continued to be integrated.

Between Wars: Restrictions and Stewards

The Navy's segregation policies limited African Americans in World War I. After the war, black enlistments were banned from 1919 to 1932. The only black sailors in uniform during that time were those who had joined before 1919 and were allowed to stay until retirement.

In 1932, black people were allowed to serve on U.S. Navy ships again, but only as stewards and mess attendants.

World War II: Pushing for Change

African-American Sailors

In June 1940, only 2.3% of the Navy's personnel were African American. Most of them were steward's mates, often called "seagoing bellhops" by the black press. After Pearl Harbor, the number of African Americans in the Navy increased, but they were still mostly restricted to steward's mate jobs.

The destroyer-escort USS Mason was the only Navy ship in World War II with an all-black crew who were not cooks or waiters. In 1995, the surviving crew members were recognized for their bravery.

The Navy did not allow women of color until January 25, 1945. Phyllis Mae Dailey was the first African-American woman sworn into the Navy. She was one of only four African American women to serve in the Navy during World War II.

The Port Chicago disaster in 1944, where 50 black sailors were convicted of mutiny, highlighted racism in the Navy. This event helped lead to a new order in 1946 that desegregated the Navy.

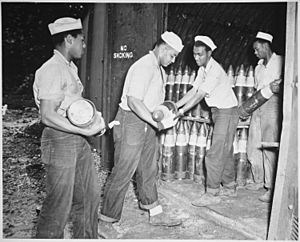

African American Seabees

In 1942, the Navy started enlisting African Americans into segregated construction battalions (or "CBs"). There were two regular CBs, the 34th and 80th NCBs, that were entirely segregated. They had white officers and black sailors.

The Navy also needed many cargo handlers. They created "Special" CBs for this job. Over 14,000 African American military personnel joined these units during World War II. By the end of the war, 15 of these Special Construction Battalions were still segregated. Later, the Special CBs became the first fully integrated units in the U.S. Navy.

The Seabees did important construction work overseas, building roads, housing, airfields, and bridges. They also fought alongside Army troops. The 17th Special Seabees were especially noted for their actions at Peleliu in September 1944. They helped the 7th Marines, who were outnumbered, by bringing ammunition and even fighting as infantrymen. Their bravery was recognized with a "Well Done" letter from the Marine Corps.

Asian-American Sailors

Before World War II, the U.S. Navy recruited Chinese Americans, but they could only serve as stewards. This changed in May 1942, when they were allowed to serve in other roles. The Korean-American Susan Ahn Cuddy was the first Asian-American woman to join the Navy in 1942. The Navy did not accept Japanese-American recruits throughout World War II.

United States Marine Corps: A Long History of Exclusion

In 1776 and 1777, a few Black American Marines served in the American Revolutionary War. But from 1798 to 1942, the U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) had a rule against African Americans serving as Marines. For 144 years, the Marines mainly recruited European Americans and Hispanic Americans, with a few Asian Americans.

The USMC started allowing African Americans in June 1942. They were accepted into segregated all-black units. Other races were accepted more easily and joined white Marine units. It took many years for black troops to be fully accepted and for segregation to end in the Corps.

New orders in 1941 and 1948 led to the integration of non-white USMC personnel. This happened in stages: segregated battalions in 1942, unified training in 1949, and finally full integration in 1960.

Background: Early Rules

The first black American to fight as a Marine was John Martin in 1776. He served for a year and a half in ship-to-ship fighting. At least 12 other black men served with American Marine units in 1776–1777.

However, when the Marine Corps was officially re-established in 1798, the rules said: "No Negro, Mulatto or Indian to be enlisted." Marine Commandant William Ward Burrows told recruiters, "You can make use of Blacks and Mulattoes while you recruit, but you cannot enlist them." This rule was meant to keep the Marines loyal and disciplined.

The Marine Corps did not recruit black soldiers. Instead, black laborers from the U.S. Navy helped with supply jobs. After World War I, the number of black people in both the Navy and Army was greatly reduced.

Franklin Roosevelt's Administration: A Push for Equality

During Franklin Delano Roosevelt's time as president, African Americans gained more political power. Civil rights groups like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) called for more equality. They argued that if America was fighting for democracy abroad, it should have democracy at home.

In April 1941, Major General Thomas Holcomb, Commandant of the Marines, said that African Americans had no right to serve as Marines. He even said he would rather have 5,000 white Marines than 250,000 black Marines.

Civil rights activists like Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph pushed Roosevelt to order fair employment for black people in the government. Many African Americans who moved to Northern and Western cities for defense jobs faced discrimination.

After activists threatened a march on Washington D.C. in July 1941, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 on June 25, 1941. This order stopped racial discrimination in federal departments, agencies, the military, and private defense companies. The planned march was then canceled.

Roosevelt and U.S. Navy Secretary Frank Knox told Holcomb to accept black recruits. Holcomb proposed a separate battalion of African Americans. This battalion would be a seacoast defense unit with anti-aircraft and anti-shipping artillery.

World War II: Black Marines and Code Talkers

In early 1942, Philip Johnston suggested that the USMC use native speakers of the Navajo language as code talkers. These code talkers would pass secret messages by radio. The first group of 29 Navajo recruits was accepted in May 1942. About 540 Navajo Marines served as code talkers during World War II. All of these soldiers served in desegregated units alongside Marines of different races.

The USMC did not form battalions of Asian Americans. Instead, they integrated Asian American recruits with European American soldiers. The first Chinese American USMC officer was commissioned in December 1943.

On June 1, 1942, the first black USMC recruits were accepted. They began basic training in August at Montford Point in North Carolina. The first black enlisted Marine was Alfred Masters. These recruits were put into the 51st Defense Battalion, a unit meant to hold land.

The black recruits were not allowed in Camp Lejeune unless a white Marine was with them. Their service papers were stamped "Colored." Their units were segregated, with all black enlisted men and white officers and drill instructors. By early 1943, black sergeants and corporals began replacing white drill instructors.

The USMC formed the 52nd Defense Battalion with more black recruits. Both the 51st and 52nd fought in the Pacific War. They were defense units behind the front lines and did not see much direct combat. In total, 19,168 African Americans joined the Marines, about 4% of the USMC's strength. About 75% of them served overseas.

About 8,000 black USMC stevedores (who load and unload ships) and ammunition handlers worked under enemy fire during operations in the Pacific. After the Battle of Saipan in June 1944, USMC General Alexander Vandegrift said of the all-black 3d Marine Ammunition Company: "The Negro Marines are no longer on trial. They are Marines, period."

At Peleliu in September 1944, the 7th Marines needed help. Two segregated companies, the 16th Marine Field Depot and the 17th Special Seabees, came to their aid. They carried ammunition to the front lines and even fought as infantrymen. Their actions were crucial in repelling a Japanese counter-attack.

1946 to 1960: Steps Towards Full Integration

After World War II, the USMC became smaller. The number of African-American Marines dropped significantly. In 1947, black Marines were forced to choose between leaving the service or becoming a steward (a food service job).

On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981. This order aimed to create equal treatment and opportunity in the U.S. military regardless of race. Both the Army and Marine Corps leaders initially defended their segregation practices. However, the Navy and the new United States Air Force announced they would follow the order.

In late 1949, all-black USMC units still existed, but black and white recruits began training together. The few black USMC officers were only assigned to black units. In 1952, during the Korean War, the Marines slowly started integrating black soldiers into combat units. By 1960, the USMC had fully integrated the races. However, racial tensions continued to appear through the next decade, a time of civil rights activism in society.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |