Code talker facts for kids

A code talker was a special person in the military during wartime. Their job was to use a language that very few people knew to send secret messages. This term is most often used for American soldiers during the World Wars. They used their knowledge of Native American languages to send coded messages.

About 400 to 500 Native Americans in the United States Marine Corps worked as code talkers. Their main job was to send secret military messages. They sent these messages over military phones or radios. They used codes they made up based on their own languages. Code talkers made sending and receiving messages much faster during World War II. They are given credit for helping win many important battles. Their secret code was never broken by the enemy.

Two main types of codes were used during World War II. The first type was a formal code. It was based on the languages of the Comanche, Hopi, Meskwaki, and Navajo peoples. They used words from their languages for each letter of the English alphabet. This was like a simple substitution cipher. The second type of code was more informal. It was a direct translation from English into the Native language. If there was no word for a military term, they used short, descriptive phrases. For example, the Navajo did not have a word for submarine. So, they called it iron fish.

The name Code Talker was first used by the United States Marine Corps. It was for people who finished special training. Today, the term is strongly linked to the Navajo speakers. They were trained in the Navajo Code during World War II by the US Marine Corps. They served in all six Marine Corps divisions and the Marine Raiders in the Pacific theater. However, Native American communicators were used even before WWII. The Cherokee, Choctaw, and Lakota peoples used their languages during World War I. Today, the term Code Talker includes military people from all Native American groups. They all used their language skills to help the United States.

Other Native American code talkers served in the United States Army during World War II. These included Lakota, Meskwaki, Mohawk, Comanche, Tlingit, Hopi, Cree, and Crow soldiers. They served in different parts of the world, like the Pacific, North Africa, and Europe.

Contents

- Languages Used by Code Talkers

- Assiniboine Code Talkers

- Basque Code Talkers (Disputed)

- Cherokee Code Talkers

- Choctaw Code Talkers

- Comanche Code Talkers

- Cree Code Talkers

- Hungarian Code Talkers

- Meskwaki Code Talkers

- Mohawk Code Talkers

- Muscogee (Seminole and Creek) Code Talkers

- Navajo Code Talkers

- Nubian Code Talkers

- Tlingit Code Talkers

- Welsh Code Talkers

- Wenzhounese Code Talkers

- Recognizing Code Talkers After the War

- See also

- Further reading

Languages Used by Code Talkers

Assiniboine Code Talkers

People who spoke the Assiniboine language worked as code talkers during World War II. They helped encrypt secret messages. One of these code talkers was Gilbert Horn Sr.. He grew up on the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in Montana. He later became a tribal judge and politician.

Basque Code Talkers (Disputed)

In 1952, a magazine called Euzko Deya reported something interesting. It said that in 1942, Captain Frank D. Carranza thought about using the Basque language for codes. He met many US Marines of Basque background in San Francisco. However, his leaders were worried. There were Basque communities in the Pacific region. This included Basque priests in Hiroshima and players in China and the Philippines. So, US Basque code talkers were not sent to these areas. They were first used for tests and to send supply information for Hawaii and Australia.

The magazine claimed that on August 1, 1942, Basque-coded messages were sent. These messages warned Admiral Chester Nimitz about a plan to remove the Japanese from the Solomon Islands. They also shared the start date, August 7, for the attack on Guadalcanal. As the war continued, there were not enough Basque speakers. So, the US military preferred using Navajo speakers instead.

However, in 2017, two researchers, Pedro Oiarzabal and Guillermo Tabernilla, disagreed with this story. They said they could not find Carranza or the other Basque lieutenants in US military records. They found a few Marines with Basque last names, but none worked in sending messages. They think Carranza's story might have been a trick by the Office of Strategic Services. It might have been to get support from Basque people for US intelligence.

Cherokee Code Talkers

The first known use of code talkers in the US military was during World War I. Cherokee soldiers in the US 30th Infantry Division spoke the Cherokee language fluently. They were given the job of sending messages while under attack. This happened in September 1918 during the Second Battle of the Somme. Their unit was working with British forces at the time.

Choctaw Code Talkers

During World War I, Captain Lawrence of the US Army heard Solomon Louis and Mitchell Bobb talking. They were speaking in Choctaw. He found out that eight Choctaw men were in his battalion. These Choctaw men in the Army's 36th Infantry Division were trained to use their language as a code. They helped the American Expeditionary Forces in several battles. This included the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. On October 26, 1918, the code talkers began their work. The "tide of battle turned within 24 hours," and the Allies were attacking within 72 hours.

Comanche Code Talkers

German leaders knew about code talkers from World War I. Before World War II, Germans sent a team of thirty scientists who study human cultures to the United States. Their goal was to learn Native American languages. But it was too hard because there were so many different Indigenous languages and dialects. Still, after learning about the German effort, the US Army decided not to use a large code talker program in Europe.

Initially, 17 Comanche code talkers joined the army. But three could not travel to Europe. So, 14 code talkers using the Comanche language took part in the Invasion of Normandy. They served in the 4th Infantry Division in Europe. These Comanche soldiers made a list of 250 code terms. They used words and phrases from their own language. Like the Navajo, they used descriptive words for things that had no direct translation. For example, the Comanche code word for tank was turtle. Bomber was pregnant bird, machine gun was sewing machine, and Adolf Hitler was crazy white man.

Two Comanche code talkers were sent to each regiment. The rest were at the 4th Infantry Division headquarters. They started sending messages shortly after landing on Utah Beach on June 6, 1944. Some were hurt, but none were killed.

In 1989, the French government gave the Comanche code talkers a special award. It was called the Chevalier of the National Order of Merit. On November 30, 1999, the United States Department of Defense gave Charles Chibitty the Knowlton Award. This was for his excellent intelligence work.

Cree Code Talkers

In World War II, the Canadian Armed Forces also used First Nations soldiers. These soldiers spoke the Cree language as code talkers. Their role was kept secret until 1963. So, their stories were not as well-known as the US code talkers. A 2016 movie called Cree Code Talkers tells the story of one such Métis person, Charles "Checker" Tomkins. Tomkins died in 2003, but he was interviewed before his death. He shared some names of other Cree code talkers. He might have been the last of his group to know about this secret operation.

Hungarian Code Talkers

In 2022, during the Russo-Ukrainian War, the Hungarian language was reportedly used by the Ukrainian army. They used it to send military information and orders. This helped them avoid being understood by the invading Russian army. It meant they did not need to encrypt and decipher messages.

Ukraine has a large Hungarian population of over 150,000 people. They mainly live in the Zakarpatska Oblast region, next to Hungary. As Ukrainian citizens, men of military age can join the army. So, the Ukrainian army has Hungarian-speaking soldiers. Hungarian is one of the most spoken languages in this region. The Hungarian language is not an Indo-European language like Ukrainian or Russian. It is a Uralic language. This makes it very different and hard for Russian speakers to understand.

Meskwaki Code Talkers

A group of 27 Meskwaki men joined the US Army together in January 1941. This was 16 percent of Iowa's Meskwaki population. During World War II, the US Army trained eight Meskwaki men. They used their native Fox language as code talkers. They were sent to North Africa. In 2013, these eight men were given the Congressional Gold Medal after their deaths. The government gave the awards to representatives of the Meskwaki community.

Mohawk Code Talkers

Mohawk language code talkers were used during World War II by the United States Army in the Pacific. Levi Oakes, a Mohawk code talker born in Canada, helped protect messages. He used Kanien'kéha, a Mohawk language. Oakes died in May 2019. He was the last of the Mohawk code talkers.

Muscogee (Seminole and Creek) Code Talkers

The Muscogee language was used as an informal code during World War II. It was used by Seminole and Creek people soldiers in the US Army. Tony Palmer, Leslie Richard, Edmund Harjo, and Thomas MacIntosh were from the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and Muscogee (Creek) Nation. They were recognized under the Code Talkers Recognition Act of 2008. The last of these code talkers, Edmond Harjo, died on March 31, 2014, at age 96. His life story was shared at the Congressional Gold Medal ceremony in 2013.

Philip Johnston, a civil engineer, suggested using the Navajo language to the United States Marine Corps. This was at the start of World War II. Johnston was a World War I veteran. He grew up on the Navajo reservation because his parents were missionaries there. He could speak a basic form of Navajo. Few non-Navajo people knew the language well. Many Navajo men joined the military after the attack on Pearl Harbor. They wanted to help with the war.

Navajo has a very complex grammar. It is not easily understood by speakers of even similar languages. At that time, it was also an unwritten language. Johnston believed Navajo could be a code that no one could break. Its complex sounds and grammar, plus its many dialects, made it very hard to understand. Only about 30 non-Navajo people could understand the language when World War II began.

In early 1942, Johnston met with Major General Clayton B. Vogel. Johnston showed how Navajo men could send and decode a three-line message in 20 seconds. This was much faster than the 30 minutes it took machines. The idea of using Navajo speakers was accepted. Vogel suggested the Marines recruit 200 Navajo. But this was cut to one small group for a test project. On May 4, 1942, twenty-nine Navajo men joined the service. They were at an old US Army Fort that was now a school. They formed platoon 382. This first group created the Navajo code at Camp Pendleton.

The First Twenty-Nine and the Code

A key part of the Navajo Code Talkers' work was that they used a coded version of their language. Other Navajo people who were not trained in the code could not understand the messages.

Platoon 382 was the Marine Corps' first all-Navajo group. Its members became known as The First Twenty-Nine. Most were from near Fort Wingate, New Mexico. The youngest was William Dean Yazzie (also known as Dean Wilson), who was only 15. The oldest was Carl N. Gorman, who was 35. Carl Gorman later became a famous artist and designed the Code Talkers' logo.

The Navajo code was formally created. It was based on the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet. This alphabet uses agreed-upon English words for letters. Spelling out every military term letter by letter would take too long in combat. So, some military terms and ideas were given unique Navajo names. For example, the word for shark meant a destroyer ship. Silver oak leaf meant the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Code Use and Post-War Talkers

A codebook was made to teach new code talkers the words and ideas. This book was only for training and was never taken into battle. Code talkers memorized all the code words. They practiced using them quickly under pressure. Navajo speakers who were not trained in the code would not understand the messages. They would only hear broken and mixed-up words.

The Navajo code talkers were praised for their skill, speed, and accuracy. At the Battle of Iwo Jima, Major Howard Connor had six Navajo code talkers working non-stop. This was during the first two days of the battle. These six sent and received over 800 messages without any mistakes. Connor later said, "If it weren't for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima."

Sometimes, other American soldiers mistook Navajo code talkers for Japanese soldiers. So, some code talkers were given a personal bodyguard. This bodyguard's main job was to protect them from their own side. According to Bill Toledo, a code talker, they had a secret second duty. If their code talker was about to be captured, they were supposed to shoot him to protect the code. Luckily, this never happened.

To make sure the code was used the same way everywhere, code talkers from different Marine divisions met in Hawaii. They talked about ways to improve the code. They added new terms and updated their codebooks. These representatives then trained other code talkers. As the war went on, more code words were added. Sometimes, informal shortcut words were made for a specific battle. These were not shared beyond that area. For example, the Navajo word for buzzard, jeeshóóʼ, was used for bomber. The code word for submarine, béésh łóóʼ, meant iron fish in Navajo. The last of the original 29 Navajo code talkers who created the code, Chester Nez, died on June 4, 2014.

Four of the last nine Navajo code talkers died in 2019 and 2020. Alfred K. Newman died in January 2019 at 94. Fleming Begaye Sr. died in May 2019 at 97. New Mexico State Senator John Pinto died in May 2019. William Tully Brown died in June 2019 at 96. Joe Vandever Sr. died in January 2020 at 96. Samuel Sandoval died in July 2022 at 98. As of 2024, only three members are still living: John Kinsel Sr., Thomas H. Begay, and Peter MacDonald.

Some Code Talkers, like Chester Nez and William Dean Yazzie, continued to serve in the Marine Corps through the Korean War. It is not confirmed if the Navajo Code was used in the Korean War or later. The Code remained secret until 1968. The Navajo code is the only spoken military code that was never broken.

Nubian Code Talkers

In the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, Egypt used Nubian-speaking Nubian people as code talkers.

Tlingit Code Talkers

During World War II, American soldiers used their native Tlingit as a code against Japanese forces. Their actions were not known for a long time. This was even after the Navajo code talkers' story became public. In March 2019, the Alaska legislature honored five Tlingit code talkers who had passed away.

Welsh Code Talkers

A system using the Welsh language was used by British forces in World War II. However, it was not used very much. In 1942, the Royal Air Force planned to use Welsh for secret messages, but it was never put into action. Welsh was used more recently in the Yugoslav Wars for less important messages.

Wenzhounese Code Talkers

China used people who spoke Wenzhounese as code talkers. This was during the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War.

Recognizing Code Talkers After the War

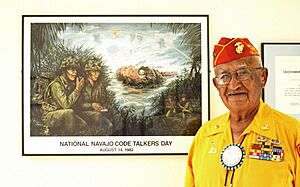

The Navajo code talkers received no public recognition until 1968. That's when their secret operation was finally revealed. In 1982, US President Ronald Reagan gave the code talkers a Certificate of Recognition. He also named August 14, 1982, as Navajo Code Talkers Day.

On December 21, 2000, President Bill Clinton signed a law. This law gave the Congressional Gold Medal to the original 29 World War II Navajo code talkers. It also gave Silver Medals to about 300 other Navajo code talkers. In July 2001, President George W. Bush honored the code talkers. He presented the medals to four surviving original code talkers. The families of the 24 original code talkers who had passed away received gold medals.

Journalist Patty Talahongva made a movie in 2006 called The Power of Words: Native Languages as Weapons of War. This movie shared the story of Hopi code talkers. In 2011, Arizona made April 23 an annual day to honor the Hopi code talkers. The Texas Medal of Valor was given to 18 Choctaw code talkers after their deaths. This was for their service in World War II.

The Code Talkers Recognition Act of 2008 was signed into law by President George W. Bush on November 15, 2008. This law recognized every Native American code talker who served in World War I or World War II. This was for all tribes except the Navajo, who had already been honored. Each tribe received a Congressional Gold Medal. Individual code talkers or their families received silver copies. As of 2013, 33 tribes have been identified and honored. One surviving code talker, Edmond Harjo, was present at a ceremony in Washington, D.C.

On November 27, 2017, three Navajo code talkers met with President Donald Trump at the White House. They were there to honor the young Native Americans who created secret coded messages during World War II. The executive director of the National Congress of American Indians, Jacqueline Pata, noted that Native Americans have a very high rate of military service.

See also

In Spanish: Locutor de claves para niños

In Spanish: Locutor de claves para niños

- Native Americans and World War II

- United States Army Indian Scouts

- Windtalkers, a 2002 American war film about Navajo radio operators in World War II

Further reading

- Aaseng, Nathan. Navajo Code Talkers: America's Secret Weapon in World War II. New York: Walker & Company, 1992.

- Connole, Joseph. "A Nation Whose Language You Will Not Understand: The Comanche Code Talkers of WWII". Whispering Wind Magazine, March, 2012, Vol. 40, No. 5, Issue #279. pp. 21–26

- Durrett, Deanne. Unsung Heroes of World War II: The Story of the Navajo Code Talkers. Library of American Indian History, Facts on File, Inc., 1998.

- Gawne, Jonathan. Spearheading D-Day. Paris: Histoire et Collections, 1999.

- Holm, Tom. Code Talkers and Warriors: Native Americans and World War II. New York: Infobase Publishing, 2007.

- Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing. 1967.

- McClain, Salley. Navajo Weapon: The Navajo Code Talkers. Tucson, Arizona: Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001.

- Meadows, William C. The Comanche Code Talkers of World War II. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002.

- Singh, Simon, The Code Book: The Science of Secrecy from Ancient Egypt to Quantum Cryptography. 2000.