Guadalcanal Campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Guadalcanal Campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||

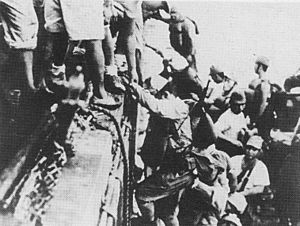

United States Marines rest in the field during the Guadalcanal campaign |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

• • |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

Robert L. Ghormley William F. Halsey, Jr. Richmond K. Turner Frank J. Fletcher Alexander A. Vandegrift Merritt A. Edson Alexander M. Patch Russell R. Waesche |

Isoroku Yamamoto Hiroaki Abe Nobutake Kondō Nishizo Tsukahara Takeo Kurita Jinichi Kusaka Shōji Nishimura Gunichi Mikawa Raizō Tanaka Hitoshi Imamura Harukichi Hyakutake |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 60,000+ men (ground forces) | 36,200 men (ground forces) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7,100 dead 7,789+ wounded 4 captured 29 ships lost 615 aircraft lost |

19,200 dead

38 ships lost 683–880 aircraft lost |

||||||

The Guadalcanal Campaign was a major battle during World War II in the Pacific. It happened between August 7, 1942, and February 9, 1943. This important fight took place on land, at sea, and in the air. Allied forces, mainly from the United States, fought against Imperial Japanese forces. The main fighting was on and around the island of Guadalcanal in the southern Solomon Islands. This was the first big attack by the Allies against Japan in the war.

On August 7, 1942, Allied forces landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida islands. Their goal was to make supply routes between the U.S., Australia, and New Zealand safer. The Battle of Guadalcanal became one of the longest campaigns in the Pacific.

Contents

Why was Guadalcanal Important?

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. This started a war between the two countries. Japan wanted to destroy the U.S. Navy and take over lands rich in natural resources. They also wanted to set up military bases to protect their empire. Japan quickly captured many places like the Philippines, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies.

The Battle of the Coral Sea stopped Japan from quickly taking over Australia. Then, the Battle of Midway greatly weakened Japan's aircraft carrier fleet.

The Allies decided to attack the southern Solomon Islands, including Guadalcanal. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) had taken over Tulagi in May 1942. They built a seaplane base there. In July 1942, the IJN started building a large airfield at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal. This airfield would let Japanese bombers threaten Australia's east coast. By August 1942, Japan had about 900 naval troops on Tulagi and 2,800 on Guadalcanal. These bases would protect Japan's main base at Rabaul. They also threatened Allied supply lines and could be used to attack Fiji, New Caledonia, and Samoa.

The Allies planned to invade the southern Solomons. U.S. Admiral Ernest King wanted to take these islands from Japan. He also wanted to invade Guadalcanal. The U.S. was also fighting Germany in Europe. So, the war in the Pacific had to share soldiers and supplies.

U.S. Army General George Marshall was against King's plan. But King insisted that the Navy and Marines would do it themselves. He told Admiral Chester W. Nimitz to plan the attacks. King won the argument, and the invasion went ahead.

The Guadalcanal attack would happen at the same time as an Allied attack in New Guinea. The goal was to capture the Admiralty Islands and the Bismarck Archipelago, including the big Japanese base at Rabaul. Eventually, they hoped to take the Philippines. U.S. Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley was put in charge of the attack in the Solomons. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz was the overall Allied commander for Pacific forces.

Preparing for Battle

In May 1942, the U.S. 1st Marine Division moved from the U.S. to New Zealand. Other Allied forces were sent to other Pacific islands. The attack was called Operation Watchtower. It was set for August 7, 1942.

At first, the plan was only for Tulagi and the Santa Cruz Islands. But when the Allies found the Japanese airfield on Guadalcanal, capturing it was added to the plan. The Japanese knew Allied forces were moving. But they thought the Allies were going to Australia or Port Moresby in New Guinea.

The Watchtower force had 75 warships and transport ships from the U.S. and Australia. They met near Fiji on July 26, 1942. They practiced landing once before heading to Guadalcanal on July 31. U.S. Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher commanded the Allied force. U.S. Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner commanded the sea and land forces. General Alexander Vandegrift led the 16,000 Allied (mostly U.S. Marine) soldiers for the landings.

The troops sent to Guadalcanal were new to battle. They had M1903 Springfield rifles and only a 10-day supply of ammunition. To get them into battle quickly, their supplies were cut to only 60 days. The Marines called this "Operation Shoestring."

First Landings and Fights

Bad weather helped the Allied force arrive near Guadalcanal unseen on the night of August 6 and morning of August 7. This surprised the Japanese defenders. The landing force split into two groups. One group attacked Guadalcanal, and the other attacked Tulagi, Florida, and nearby islands.

Allied warships bombed the beaches. U.S. aircraft from carriers bombed Japanese forces and destroyed 15 Japanese seaplanes near Tulagi.

About 3,000 U.S. Marines attacked Tulagi and two small islands nearby, Gavutu and Tanambogo. The 886 Japanese naval forces fought back fiercely. The Marines captured all three islands: Tulagi on August 8, and Gavutu and Tanambogo by August 9. Almost all the Japanese defenders were killed. The Marines lost 122 men.

The landings on Guadalcanal faced much less resistance. On August 7, 11,000 U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal without a fight. They stopped for the night about 1,000 meters from the Lunga Point airfield. The next day, the Marines advanced and captured the airfield by 4:00 PM on August 8.

The Japanese construction workers and soldiers had left the airfield area. They fled about 3 miles west to the Matanikau River and Point Cruz area. They left behind food, supplies, equipment, and 13 dead.

On August 7 and 8, Japanese aircraft from Rabaul attacked the Allied forces several times. They set fire to the transport ship USS George F. Elliot (which sank two days later). They also heavily damaged the destroyer USS Jarvis. In these air attacks, Japan lost 36 aircraft, while the U.S. lost 19.

After these fights, Admiral Fletcher was worried about his carrier aircraft losses. He was also concerned about Japanese air attacks and his ships' fuel levels. Fletcher pulled his carrier forces back from the Solomon Islands on the evening of August 8. Because of this loss of air cover, Admiral Turner pulled his ships back from Guadalcanal. This happened even though less than half of the supplies and heavy equipment for the troops had been unloaded. Turner planned to unload as much as possible on the night of August 8 and then leave early on August 9.

Battle of Savo Island

That night, as the transport ships unloaded, two groups of Allied cruisers and destroyers were defeated. British Rear Admiral Victor Crutchley led them. A Japanese force of seven cruisers and one destroyer, led by Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, attacked them.

In the Battle of Savo Island, one Australian and three American cruisers were sunk. One American cruiser and two destroyers were damaged. The Japanese had only minor damage to one cruiser. Mikawa did not know Fletcher was leaving with the U.S. carriers. He immediately went back to Rabaul without attacking the transport ships. Mikawa was worried about U.S. carrier air attacks in daylight. Without carrier air cover, Turner decided to pull back his remaining naval forces by the evening of August 9. This left the Marines on shore without much heavy equipment, supplies, and troops still on the transport ships. Mikawa's choice not to destroy the Allied transport ships was a big mistake.

Early Ground Fights

The 11,000 Marines on Guadalcanal first set up defenses around Lunga Point and the airfield. They also moved supplies ashore and finished the airfield. By August 18, the airfield was ready. They had five days of food from the ships, plus captured Japanese food, giving them 14 days total. To save supplies, troops ate only two meals a day.

Many Allied troops got sick with dysentery by mid-August. Tropical diseases affected both sides. Most Japanese and Korean workers gathered to the west and ate coconuts. A Japanese naval outpost was also at Taivu Point, about 35 kilometers (22 miles) east of the Lunga perimeter. On August 8, a Japanese destroyer brought 113 troops to the Matanikau area.

On August 19, General Vandegrift sent three companies of the U.S. 5th Marine Regiment to attack Japanese troops west of the Matanikau. They killed about 65 Japanese soldiers and lost four Marines. This was the first of many fights around the Matanikau River.

On August 20, the escort carrier USS Long Island brought Marine aircraft to Henderson Field. These planes became known as the "Cactus Air Force" (CAF). Japanese bombers attacked almost every day. On August 22, five U.S. Army P-400 Airacobra planes arrived.

Battle of the Tenaru River

In response to the Allied landings, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters ordered the 17th Army at Rabaul to retake Guadalcanal. This army was led by Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake. Japanese naval units, including the Combined Fleet under Isoroku Yamamoto, would support them.

Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki's unit, with about 917 soldiers, landed from destroyers at Taivu Point after midnight on August 19. They marched 9 miles west towards the Marines. Ichiki thought there were not many Allied soldiers.

Ichiki's soldiers attacked Marine positions at Alligator Creek early on August 21. This attack was defeated with heavy Japanese losses in what became known as the Battle of the Tenaru. The Marines then attacked Ichiki's remaining troops, killing many more. Ichiki was among the dead. Only 128 of the original 917 soldiers survived. The survivors went back to Taivu Point to wait for new orders.

Battle of the Eastern Solomons

As the Tenaru battle ended, more Japanese troops were on their way. Three transport ships left Truk on August 16. They carried 1,400 soldiers from Ichiki's regiment and 500 naval marines. Thirteen warships, led by Japanese Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka, protected the transports. Tanaka planned to land the troops on Guadalcanal on August 24.

To cover the landings and retake Henderson Field, Yamamoto sent a carrier force from Truk. This force, led by Chūichi Nagumo, included three carriers and 30 other warships.

Three U.S. carrier forces, led by Admiral Fletcher, approached Guadalcanal to attack the Japanese. On August 24 and 25, the two carrier forces fought the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. Both fleets pulled back after taking damage. Japan lost one light aircraft carrier. Tanaka's convoy was heavily damaged by air attacks from Henderson Field. One transport ship sank. The convoy then turned back to the Shortland Islands to transfer troops to destroyers for delivery to Guadalcanal.

Air Battles and Defenses

Throughout August, more U.S. aircraft arrived at Guadalcanal. By the end of August, 64 aircraft were at Henderson Field. Air battles between the CAF and Japanese planes from Rabaul happened almost daily. Between August 26 and September 5, the U.S. lost about 15 aircraft, and Japan lost about 19. Most downed U.S. aircrews were rescued, but most Japanese aircrews were not. The eight-hour round trip from Rabaul to Guadalcanal (about 1,120 miles) made it hard for the Japanese to attack Henderson Field.

Australians on Bougainville and New Georgia islands often warned of Japanese air strikes. This gave U.S. fighters time to take off and attack.

Between August 21 and September 3, three Marine battalions, including Merritt A. Edson's 1st Raider Battalion, moved to Guadalcanal. These units added about 1,500 troops to the 11,000 men defending Henderson Field.

Small Allied naval convoys arrived at Guadalcanal on August 23, August 29, September 1, and September 8. They brought more food, ammunition, fuel, and technicians for the Marines. The September 1 convoy also brought 392 construction engineers to work on Henderson Field.

The Tokyo Express

By August 23, Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi's 35th Infantry Brigade reached Truk. They were loaded onto slow transport ships for Guadalcanal. But the damage to Tanaka's convoy during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons made Japan change its plan. They decided not to send more troops by slow transports. Instead, Kawaguchi's soldiers were sent to Rabaul.

From Rabaul, the Japanese planned to deliver Kawaguchi's men to Guadalcanal using destroyers. These destroyers could usually make a round trip to Guadalcanal and back in one night. This reduced their risk of Allied air attack.

Allied Forces called these runs the "Tokyo Express".

Using destroyers made it hard to bring heavy equipment and supplies like artillery, vehicles, and much food and ammunition. Also, this used destroyers that the Japanese Navy needed for other tasks. Allied naval commanders did not fight Japanese naval forces at night. But any Japanese ship within 200 miles of Henderson Field during daylight was in great danger from air attacks. This situation lasted for several months.

Between August 29 and September 4, Japanese ships landed almost 5,000 troops at Taivu Point. This included most of the 35th Infantry Brigade and other units. General Kawaguchi, who landed on August 31, took command of all Japanese forces on Guadalcanal. Another 1,000 soldiers landed at Kamimbo, west of the Lunga perimeter.

Major Battles Continue

Battle of Edson's Ridge

On September 7, Kawaguchi planned to attack the airfield on Guadalcanal. His plan was a surprise night attack. His main force of 3,000 men would attack from the south. By September 7, most of Kawaguchi's troops marched towards Lunga Point. About 250 Japanese troops stayed behind to guard supplies at Taivu.

Meanwhile, U.S. Marine scouts reported Japanese troops at Taivu. General Edson planned a raid. On September 8, Edson's men landed near Taivu and captured Tasimboko. The Japanese retreated into the jungle.

In Tasimboko, Edson's troops found Kawaguchi's main supply depot. It had lots of food, ammunition, medical supplies, and a powerful shortwave radio. After destroying everything, the Marines returned to the Lunga perimeter. The captured documents showed that at least 3,000 Japanese troops were on the island and planning an attack.

Edson and Colonel Gerald C. Thomas believed the Japanese attack would come at a narrow, grassy, 1,000-yard-long coral ridge south of Henderson Field. This ridge, called Lunga Ridge, was a good way to reach the airfield and was undefended. On September 11, Edson's 840 men were sent to defend the ridge.

On the night of September 12, Kawaguchi's 1st Battalion attacked the Raiders between the Lunga River and the ridge. One Marine company had to fall back to the ridge before the Japanese stopped their attack. The next night, Kawaguchi attacked Edson's 830 Raiders with 3,000 troops and artillery. The Japanese attack began after dark. After breaking through some Marine defenses, the attack was stopped by Marines guarding the northern part of the ridge.

Two companies from Kawaguchi's 2nd Battalion moved up the southern edge of the ridge. They pushed Edson's troops back to Hill 123 in the center of the ridge. Throughout the night, the Marines fought against Japanese attacks, sometimes hand-to-hand. The Marines also had artillery. Japanese groups that got past the ridge towards the airfield were also pushed back.

Other Japanese attacks in different places were also stopped. On September 14, Kawaguchi led the survivors on a five-day march west to the Matanikau Valley to join other Japanese units. Kawaguchi's forces lost about 850 men, and the Marines lost 104.

On September 15, Hyakutake learned of Kawaguchi's loss. Japanese leaders decided that Guadalcanal might become the most important battle of the war. This loss affected Japanese operations elsewhere. Hyakutake realized he could not send enough troops to Guadalcanal and also support the Japanese attacks in New Guinea.

Hyakutake ordered his troops in New Guinea to pull back until the Guadalcanal battle was over. He sent more troops to Guadalcanal for another try to recapture Henderson Field.

Reinforcements Arrive

As Japanese troops gathered west of the Matanikau, U.S. forces strengthened their Lunga defenses. On September 14, Vandegrift moved another battalion from Tulagi to Guadalcanal. On September 18, an Allied naval convoy brought 4,157 more men, 137 vehicles, tents, fuel, ammunition, and equipment to Guadalcanal. These new soldiers helped Vandegrift create a strong defense around the Lunga perimeter. While protecting this convoy, the aircraft carrier USS Wasp was sunk by the Japanese submarine I-19. For a while, only one Allied aircraft carrier (USS Hornet) was left in the South Pacific.

Vandegrift also replaced officers who were not performing well and promoted junior officers who had done well. Colonel Merritt Edson was given command of the 5th Marine Regiment.

The air war over Guadalcanal paused due to bad weather. Both sides reinforced their air units. The Japanese brought 85 fighters and bombers to Rabaul, while the U.S. brought 23 fighters and attack aircraft to Henderson Field. On September 20, Japan had 117 aircraft at Rabaul, and the Allies had 71 at Henderson Field. The air war started again with a Japanese air raid on September 27.

The Japanese began preparing for their next attack on Henderson Field. More Japanese troops and supplies arrived by destroyers. The Japanese 2nd and 38th Infantry Divisions were moved from the Dutch East Indies to Rabaul starting September 13. The Japanese planned to send 17,500 troops from these two divisions to Guadalcanal for a major attack on the Lunga Perimeter around October 20, 1942.

Fights Along the Matanikau River

Vandegrift knew that Kawaguchi's troops had gone back to the area west of the Matanikau River. He also knew that many Japanese groups were between the Lunga Perimeter and the river. Vandegrift decided to attack the scattered Japanese groups east of the Matanikau. He also wanted to stop the main Japanese force from getting stronger so close to the Marine defenses.

The first U.S. Marine attack between September 23 and 27 was defeated by Kawaguchi's troops. Three Marine companies were surrounded and suffered many dead and wounded. They escaped with help from the destroyer USS Monssen (DD-436) and boats from the U.S. Coast Guard.

In the second attack, between October 6 and 9, a larger Marine force crossed the Matanikau River. They attacked newly landed Japanese forces. The Marines caused many deaths and injuries for the Japanese. This attack forced the Japanese to retreat from their positions east of the Matanikau. This caused problems for Japanese plans for a major attack on the U.S. defenses.

Battle of Cape Esperance

Throughout late September and early October, Japanese destroyers brought troops from the Japanese 2nd Infantry Division to Guadalcanal. The Japanese Navy promised to support the Army's attack by delivering troops, equipment, and supplies. They also planned more air attacks on Henderson Field and warship bombings of the airfield.

Millard Harmon, commander of United States Army forces in the South Pacific, believed U.S. Marine forces on Guadalcanal needed new soldiers. On October 8, 2,837 men from the 164th Infantry Regiment boarded ships for Guadalcanal. To protect these transports, Task Force 64, with four cruisers and five destroyers under U.S. Rear Admiral Norman Scott, was sent to attack any Japanese ships approaching Guadalcanal.

The Japanese were not expecting any U.S. Navy ships to stop their supply missions. Just before midnight on October 11, Scott's warships detected a Japanese force on radar. Scott's force was in a good position to fire. They opened fire, sinking one Japanese cruiser and one destroyer. They heavily damaged another cruiser, seriously wounded the Japanese commander, and forced the rest of the Japanese warships to leave without bombing the airfield.

One of Scott's destroyers was sunk, and one cruiser and another destroyer were heavily damaged. The Japanese supply convoy unloaded at Guadalcanal and left without being found by Scott's force. Later, on October 12, four Japanese destroyers from the supply convoy turned back to help the damaged Japanese warships. Air attacks from Henderson Field sank two of these destroyers later that day. The U.S. Army troops reached Guadalcanal as planned the next day.

Battleship Bombing of Henderson Field

Even after the U.S. victory at Cape Esperance, the Japanese continued planning a large attack for later in October. They decided to risk using slow warships to deliver their men and supplies.

On October 13, a convoy of six cargo ships with eight destroyers left the Shortland Islands for Guadalcanal. The convoy carried 4,500 troops, naval marines, heavy artillery, and tanks.

To protect the convoy from air attacks, Yamamoto sent two battleships from Truk to bomb Henderson Field. At 1:33 AM on October 14, Kongō and Haruna, protected by other ships, reached Guadalcanal. They fired at Henderson Field from about 16,000 meters away. For over an hour, the two battleships fired 973 large shells into the Lunga perimeter, mostly on the airfield. Many shells were designed to destroy land targets. The bombing heavily damaged both runways, burned almost all the airplane fuel, destroyed 48 of the CAF's 90 aircraft, and killed 41 men. The battleships then returned to Truk.

Despite the heavy damage, soldiers at Henderson were able to fix one runway within a few hours. Seventeen SBDs and 20 Wildcats were flown to Henderson from Espiritu Santo. U.S. Army and Marine transport aircraft began bringing airplane fuel to Guadalcanal.

The U.S. knew about the large Japanese convoy approaching. They tried to attack it before it reached Guadalcanal. Using fuel from destroyed aircraft and a hidden tank, the CAF attacked the convoy twice on the 14th, but caused no damage.

The Japanese convoy reached Guadalcanal at midnight on October 14 and began unloading. Throughout October 15, CAF aircraft from Henderson bombed and machine-gunned the convoy, destroying three cargo ships. The rest of the convoy left that night, having unloaded all troops and about two-thirds of the supplies.

Several Japanese heavy cruisers also bombed Henderson on the nights of October 14 and 15. They destroyed a few more CAF aircraft but did not damage the airfield.

Battle for Henderson Field

Between October 1 and 17, the Japanese delivered 15,000 troops to Guadalcanal. This gave Hyakutake 20,000 troops for his planned attack. Since they had lost their positions east of the Matanikau, the Japanese decided that an attack along the coast would be too hard. Hyakutake decided to attack from south of Henderson Field.

His 2nd Division, with 7,000 soldiers, was ordered to attack the American defenses from the south, near the east bank of the Lunga River. The attack date was set for October 22, then changed to October 23. To trick the Americans, Hyakutake's heavy artillery and five infantry battalions attacked the American defenses from the west.

The Japanese thought there were 10,000 American troops on the island, but there were actually 23,000.

On October 12, Japanese engineers began cutting a trail, called the "Maruyama Road." This 15-kilometer trail went from the Matanikau towards the southern part of the U.S. Lunga perimeter. It crossed rivers, ravines, ridges, and thick jungle. Between October 16 and 18, the 2nd Division began their march along the Maruyama Road.

By October 23, Maruyama's forces were struggling to get through the jungle to reach the American forces. Hyakutake delayed the attack to 7:00 PM on October 24. The Americans did not know Maruyama's forces were coming.

Sumiyoshi was told about the delay, but he could not contact his troops. So, at dusk on October 23, two battalions and nine tanks attacked the U.S. Marine defenses at the Matanikau. U.S. Marine artillery, cannons, and rifle fire defeated the attacks. All the tanks were destroyed, and many Japanese soldiers were killed. Only a few Marines were killed or wounded.

Finally, late on October 24, Maruyama's forces reached the U.S. Lunga perimeter. For two nights, Maruyama's troops attacked positions defended by U.S. Marines and Army soldiers. The American units, with rifles, machine guns, mortars, and anti-tank guns, caused terrible damage to the Japanese. A few small Japanese groups broke through but were all killed over the next few days.

More than 1,500 of Maruyama's troops were killed in the attacks, while the Americans lost about 60. Over the same two days, American aircraft from Henderson Field destroyed 14 Japanese aircraft and sank a light cruiser.

Further Japanese attacks near the Matanikau on October 26 were also defeated with heavy losses for the Japanese. By 8:00 AM on October 26, Hyakutake stopped the attacks and ordered his forces to retreat. About half of Maruyama's survivors were ordered back to the Matanikau Valley. Another unit was told to go to Koli Point, east of the Lunga perimeter.

Soldiers from the 2nd Division reached the 17th Army headquarters at Kokumbona on November 4. The 2nd Division had many battle deaths, injuries, and illnesses. It was too weak to attack again. It fought as a defensive force for the rest of the battle.

The Japanese lost 2,200–3,000 troops in the battle, while the Americans lost around 80.

Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands

At the same time Hyakutake's troops were attacking, Japanese aircraft carriers and other warships, led by Isoroku Yamamoto, moved near the southern Solomon Islands. They hoped to defeat any Allied naval forces, especially carriers. Allied naval carrier forces, now led by William Halsey, Jr., also hoped to fight the Japanese.

Nimitz had replaced Ghormley with Halsey on October 18. He felt Ghormley was too negative to lead Allied forces in the South Pacific.

The two opposing carrier forces fought on the morning of October 26 in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. Both sides launched air attacks. Allied ships had to retreat after one carrier was sunk (Hornet) and another (Enterprise) was heavily damaged. The Japanese carrier forces also pulled back because of high aircraft and aircrew losses and major damage to two carriers.

The Japanese won in terms of ships sunk and damaged. However, the Japanese lost many experienced aircrews, which helped the Allies, who did not lose many aircrews. The Japanese carriers did not play any more important roles in the battle.

November Land Actions

To build on his victory, Vandegrift sent six Marine battalions, joined by one U.S. Army battalion, to attack west of the Matanikau. This attack, led by Merritt Edson, aimed to capture Kokumbona, the 17th Army headquarters.

Japanese army troops defended the Point Cruz area. These troops were in poor condition from battle, disease, and lack of food.

The American attack began on November 1. It destroyed Japanese forces in the Point Cruz area by November 3. The Americans seemed close to capturing Kokumbona. Then, American forces found newly landed Japanese troops near Koli Point, east of the Lunga perimeter.

To deal with these new Japanese troops, Vandegrift stopped the Matanikau attack on November 4. The Americans had 71 deaths, and the Japanese had around 400 killed.

At Koli Point early on November 3, five Japanese destroyers landed 300 army troops. They were sent to help Colonel Toshinari Shōji and his troops, who were going to Koli Point after the Battle for Henderson Field.

When Vandegrift learned of the Japanese landing, he sent a Marine battalion to attack them. The Japanese soldiers pushed the Marine battalion back towards the Lunga perimeter.

Vandegrift then ordered more Marine and Army battalions to attack the Japanese there. As the American troops moved, Shōji and his soldiers began to arrive at Koli Point. Starting November 8, the American troops tried to surround Shōji's forces.

Hyakutake ordered Shōji to leave Koli and rejoin Japanese forces at Kokumbona. Between November 9 and 11, Shōji and between 2,000 and 3,000 of his men escaped into the jungle to the south. On November 12, the Americans killed all remaining Japanese soldiers. The American forces had 40 killed and 120 wounded.

On November 4, two companies from the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion, led by Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson, landed by boat at Aola Bay, 40 miles east of Lunga Point. Carlson's raiders and U.S. Army troops were told to protect 500 Seabees building an airfield there.

The Aola airfield construction stopped in late November because the land was not good for an airfield.

On November 5, Vandegrift ordered Carlson to attack any of Shōji's forces that had escaped from Koli Point. Carlson and his troops went on a 29-day patrol. During the patrol, Carlson's soldiers fought several battles with Shōji's retreating forces, killing almost 500 of them.

Besides battle deaths, tropical diseases and lack of food caused more of Shōji's men to die. By the time Shōji's forces reached the Lunga River in mid-November, only about 1,300 men remained. When Shōji reached the 17th Army positions, only 700 to 800 survivors were still with him. Most survivors joined other Japanese units defending the Mount Austen and upper Matanikau River area.

Japanese destroyer trips on November 5, 7, and 9 brought more troops from the Japanese 38th Infantry Division to Guadalcanal. These fresh troops were placed in the Point Cruz and Matanikau area. They stopped American attacks on November 10 and 18. The Americans and Japanese faced each other along a line west of Point Cruz for the next six weeks.

After losing the Battle for Henderson Field, the Japanese Army planned to try again to capture the airfield in November 1942. They needed new soldiers before the attack. The Army asked Yamamoto for help to deliver the new troops and support the next attack.

Yamamoto provided 11 large transport ships to carry 7,000 troops from the 38th Infantry Division, their ammunition, food, and heavy equipment from Rabaul to Guadalcanal. He also provided warships, including two battleships. These battleships, Hiei and Kirishima, would bomb Henderson Field on the night of November 12–13. This would destroy the airfield and aircraft, allowing the slow transports to unload safely the next day. Vice Admiral Hiroaki Abe commanded the warship force.

In early November, Allied forces learned that the Japanese were preparing to try to capture Henderson Field again. So, the U.S. sent a convoy carrying Marines, two U.S. Army battalions, and supplies to Guadalcanal on November 11. Two task groups, led by Rear Admirals Daniel J. Callaghan and Norman Scott, and aircraft from Henderson Field protected the supply ships. The ships were attacked several times on November 11 and 12, but most were unloaded without serious damage.

U.S. aircraft spotted Abe's bombing force approaching and warned the Allied command. Turner sent all usable combat ships under Callaghan to protect the troops from the expected Japanese naval attack and landing. He also ordered the supply ships at Guadalcanal to leave by early evening November 12. Callaghan's force had two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and eight destroyers.

Around 1:30 AM on November 13, Callaghan's force met Abe's bombing group between Guadalcanal and Savo Island. Abe's force included two battleships, one light cruiser, and 11 destroyers. In the darkness, the two forces opened fire. Abe's warships sank or badly damaged all but one cruiser and one destroyer in Callaghan's force. Both Callaghan and Scott were killed.

Two Japanese destroyers were sunk, and another destroyer and Hiei were heavily damaged. Despite defeating Callaghan's force, Abe ordered his warships to pull back without bombing Henderson Field. Hiei sank later that day after air attacks. Because Abe failed to destroy Henderson Field, Yamamoto ordered the troop transport convoy to wait an extra day.

Yamamoto ordered Nobutake Kondō to gather another bombing force from Truk and Abe's force to attack Henderson Field on November 15.

At 2:00 AM on November 14, a cruiser and destroyer force bombed Henderson Field. The bombing caused some damage but did not destroy the airfield or most of its aircraft. As this force went back to Rabaul, Tanaka's transport convoy, thinking Henderson Field was destroyed, began its trip towards Guadalcanal.

Throughout November 14, aircraft from Henderson Field and Enterprise attacked Tanaka's ships, sinking one heavy cruiser and seven transports. Most of the troops were rescued by Tanaka's escorting destroyers and returned to the Shortlands. After dark, Tanaka and the remaining four transports continued towards Guadalcanal as Kondo's force approached to bomb Henderson Field.

To attack Kondo's force, Halsey, who had few undamaged ships, sent two battleships, Washington and South Dakota, and four destroyers. The U.S. force, led by Willis Augustus Lee aboard Washington, reached Guadalcanal and Savo Island just before midnight on November 14. Kondo's force had Kirishima plus two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and nine destroyers. After the two forces met, Kondo's force quickly sank three U.S. destroyers and heavily damaged the fourth. The Japanese warships then damaged South Dakota. As Kondo's warships focused on South Dakota, Washington approached and fired on Kirishima, causing serious damage. After chasing Washington, Kondo ordered his warships to pull back without bombing Henderson Field. One of Kondo's destroyers was also sunk.

As Kondo's ships pulled back, the four Japanese transports landed near Tassafaronga on Guadalcanal at 4:00 AM and began unloading. At 5:55 AM, U.S. aircraft and artillery attacked the transports, destroying all four ships and most of their supplies.

Only 2,000–3,000 of the army troops made it ashore. Because most troops and supplies could not be delivered, the Japanese had to cancel their planned November attack on Henderson Field.

On November 26, Japanese Lieutenant General Hitoshi Imamura took command of the new Japanese Eighth Area Army at Rabaul. This command included Hyakutake's 17th Army and the 18th Army in New Guinea.

One of Imamura's first goals was to retake Henderson Field and Guadalcanal. However, the Allied attack at Buna in New Guinea changed Imamura's plans.

Because the Allied attempt to take Buna was a bigger threat to Rabaul, Imamura delayed sending new troops to Guadalcanal. He focused on New Guinea instead.

Battle of Tassafaronga

The Japanese continued to have trouble delivering enough supplies to their troops on Guadalcanal. Attempts to use only submarines in late November did not provide enough food for Hyakutake's forces.

Another attempt to set up bases in the central Solomons to send barges to Guadalcanal also failed due to Allied air attacks. On November 26, the 17th Army told Imamura they lacked food. Some front-line units had not been supplied for six days. This forced the Japanese to go back to using destroyers to deliver supplies.

Eighth Fleet sailors came up with a plan to reduce the time destroyers were exposed to Allied attack. They would fill large oil or gas drums with medical supplies and food and tie them together with rope. When destroyers arrived at Guadalcanal, they would cut the drums loose, and a boat from shore would pick up the rope.

The Eighth Fleet's Guadalcanal Reinforcement Unit (the Tokyo Express) was told to make five deliveries to Tassafaronga on the night of November 30 using this method. Tanaka's unit had eight destroyers, with six carrying 200 to 240 drums of supplies each.

When Halsey learned about the Japanese supply attempt, he ordered the new Task Force 67, with four cruisers and four destroyers under U.S. Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright, to attack Tanaka's force. Two more destroyers joined Wright's force on November 30.

At 10:40 PM on November 30, Tanaka's force arrived off Guadalcanal and prepared to unload the drums. Meanwhile, Wright's warships were approaching. Wright's destroyers detected Tanaka's force on radar and asked to attack with torpedoes. Wright waited four minutes before giving permission.

This allowed Tanaka's force to escape being torpedoed. All American torpedoes missed. At the same time, Wright's cruisers opened fire, hitting and destroying one Japanese destroyer. The rest of Tanaka's warships stopped the supply mission, turned, and launched 44 torpedoes towards Wright's cruisers.

The Japanese torpedoes hit and sank the U.S. cruiser Northampton. They also heavily damaged the cruisers Minneapolis, New Orleans, and Pensacola. The rest of Tanaka's destroyers escaped without damage, but they failed to deliver any supplies to Guadalcanal.

By December 7, 1942, Hyakutake's forces were losing about 50 men each day from lack of food, disease, and Allied attacks. Further attempts by Tanaka's destroyers to deliver supplies on December 3, 7, and 11 did not solve the problem. One of Tanaka's destroyers was sunk by a U.S. PT boat torpedo.

Japan Decides to Leave

On December 12, the Japanese Navy considered leaving Guadalcanal. At the same time, some army officers at the Imperial General Headquarters (IGH) said retaking Guadalcanal would be impossible. A group visited Rabaul on December 19 and talked to Imamura.

When this group returned to Tokyo, they recommended that Guadalcanal be abandoned. The IGH's top leaders agreed on December 26. They ordered plans for a withdrawal from Guadalcanal. A new defense line would be set up in the central Solomons, and soldiers and weapons would be sent to New Guinea.

On December 28, General Hajime Sugiyama and Admiral Osami Nagano told Emperor Hirohito about the decision to leave Guadalcanal. On December 31, the Emperor agreed. The Japanese secretly began preparing for the evacuation, called Operation Ke, set to begin in January 1943.

Battles for Mount Austen and the Ridges

By December, the tired 1st Marine Division was pulled back for rest. Over the next month, the U.S. XIV Corps took over operations. This corps included the 2nd Marine Division and the U.S. Army's 25th Infantry and Americal Divisions. U.S. Army Major General Alexander Patch replaced Vandegrift as commander of Allied forces on Guadalcanal. By January, there were over 50,000 men.

On December 18, Allied forces (mainly U.S. Army) began attacking Japanese soldiers on Mount Austen. A strong Japanese fort, called the Gifu, made the attacks hard. The Americans had to stop their attacks on January 4.

The Allies attacked the Japanese again on January 10 on Mount Austen. They also attacked two nearby ridges called the Seahorse and the Galloping Horse. The Allies captured all three by January 23. At the same time, U.S. Marines advanced along the north coast. The Americans lost about 250 killed, while the Japanese lost around 3,000.

The Ke Evacuation

On January 14, destroyers brought troops to guard the Ke evacuation. Japanese warships and aircraft moved around Rabaul and Bougainville to prepare to withdraw their troops. Allied forces saw the Japanese movements but thought they were another attempt to retake Henderson Field and Guadalcanal.

Patch, worried about another Japanese attack, sent only a small part of his troops to continue attacking Hyakutake's forces. On January 29, Halsey sent a supply convoy to Guadalcanal, protected by a cruiser task force. Japanese torpedo bombers attacked the task force and heavily damaged the U.S. cruiser Chicago. The next day, more torpedo aircraft attacked and sank Chicago.

Halsey ordered the rest of the task force to return to base. He directed his other naval forces to wait in the Coral Sea, south of Guadalcanal, ready to respond to a Japanese attack.

The Japanese 17th Army pulled back to the west coast of Guadalcanal. Rear guard groups stopped the American attacks. On the night of February 1, 20 destroyers removed 4,935 soldiers, mainly from the 38th Division, from the island. The Japanese and Americans each lost a destroyer from air and naval attacks.

On the nights of February 4 and 7, the destroyers completed removing most of the remaining Japanese forces from Guadalcanal. Allied forces did not try to stop these efforts, except for some air attacks. In total, the Japanese removed 10,652 men from Guadalcanal. On February 9, Patch realized the Japanese were gone and declared Guadalcanal secure for Allied forces, ending the battle.

What Happened After?

After the Japanese left, Guadalcanal and Tulagi became major Allied bases. These bases helped the Allies advance further up the Solomon Islands. Besides Henderson Field, two more fighter runways were built at Lunga Point, and a bomber airfield was built at Koli Point.

Naval ports were built at Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida. The area around Tulagi became an important base for Allied warships and transport ships. Major ground units stayed in camps on Guadalcanal before being sent further up the Solomons.

After Guadalcanal, the Japanese had to defend themselves in the Pacific. The effort to send new troops to Guadalcanal had weakened Japanese efforts elsewhere. This helped the Australian and American attack in New Guinea succeed. This led to the capture of the bases of Buna and Gona in early 1943.

In June, the Allies launched Operation Cartwheel. This aimed to cut off Rabaul and the forces there. This helped the South West Pacific campaign under General Douglas MacArthur. It also helped the Central Pacific island hopping campaign under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz. Both efforts brought the Allies closer to Japan. The remaining Japanese defenses in the South Pacific were destroyed or bypassed.

Why was Guadalcanal So Important?

Resources and Losses

The Battle of Guadalcanal was one of the first long battles in the Pacific. Both sides found it very hard to organize. For the U.S., it was a learning experience in how to move troops and supplies by air. Japan could not get enough supplies because they did not control the air. This forced them to use barges, destroyers, and submarines, which did not work well.

Early in the battle, the Americans lacked resources. They lost cruisers and carriers. It took months for new ships to be built.

The U.S. Navy lost so many ships and men that it did not release total casualty numbers for years. However, as the American public learned about the bravery of the forces on Guadalcanal, more resources were sent to the area.

This was a big problem for Japan. Their factories could not produce as much as the Americans. So, as the battles continued, the Japanese lost equipment they could not replace. The Americans, however, replaced and even added to their forces.

The Guadalcanal battles caused Japan to lose a lot of equipment and soldiers. About 25,000 experienced troops were killed. These losses meant Japan could not achieve its goals in the New Guinea campaign. Japan also lost control of the southern Solomons and could no longer stop Allied shipping to Australia.

Japan's main base at Rabaul was threatened by Allied air power. Japanese land, air, and naval forces were lost. The Japanese could not replace the aircraft and ships destroyed. They also could not replace their highly trained crews, especially naval aircrews, as quickly as the Allies.

Strategic Importance

After the victory at the Battle of Midway, America had naval strength in the Pacific equal to Japan's. But it was only after the Allied victories in Guadalcanal and New Guinea that Japanese attacks stopped. The Guadalcanal Campaign ended all Japanese expansion attempts. It put the Allies in a position of power. This Allied victory was the first step in winning other battles that eventually led to the surrender of Japan and the occupation of the Japanese home islands.

The "Europe first" policy of the United States meant they first focused on defending against Japan to defeat Germany. However, Admiral King's argument for the Guadalcanal invasion convinced President Franklin D. Roosevelt that the Pacific War could also be won. By the end of 1942, it was clear that Japan had lost the Guadalcanal campaign. This was very bad for Japan's plans to defend their empire.

The military victory for the Allies was important. The psychological victory was also important. The Allies had beaten Japan's best land, air, and warship forces. After Guadalcanal, Allied personnel feared the Japanese military much less. Also, the Allies began to believe they could win the Pacific War.

Interesting Facts About The Battle of Guadalcanal

- The battle was fought on land, in the sea, and in the air.

- Guadalcanal was called the "island of death" by the Japanese soldiers. Many died of starvation because their supply lines were cut.

- This battle was the first big victory for the Allies against Japan in the Pacific.

- The U.S. Army, Coast Guard, U.S. Navy, and U.S. Marines all fought in the battle.

- The attack was secretly called Operation Watchtower.

Images for kids

-

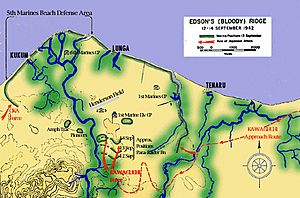

Map of the Lunga perimeter on Guadalcanal showing the approach routes of the Japanese forces and the locations of the Japanese attacks during the battle. Oka's attacks were in the west (left), the Kuma Battalion attacked from the east (right) and the Center Body attacked "Edson's Ridge" (Lunga Ridge) in the lower center of the map.

-

From left to right: Lieutenant Colonel Leonard B. Cresswell (1st Battalion), Lieutenant Colonel Edwin A. Pollock (Executive Officer 1st Marines), Colonel Clifton B. Cates (Commanding Officer 1st Marines), Lieutenant Colonel William N. McKelvy (3rd Battalion) and Lieutenant Colonel William W. Stickney (2nd Battalion) on Guadalcanal, October 1942

See also

In Spanish: Campaña de Guadalcanal para niños

In Spanish: Campaña de Guadalcanal para niños