Battle of the Coral Sea facts for kids

The Battle of the Coral Sea was a major naval battle fought in the Pacific Ocean during World War II. It happened from May 4 to May 8, 1942. This battle was between the Japanese Navy and the Allied navies and air forces from the United States and Australia.

This was the first battle where aircraft carriers fought each other. It was also the first naval battle where the ships never saw each other. Instead, planes from the carriers attacked the enemy ships.

Japan planned to invade and take over Port Moresby in New Guinea and Tulagi in the Solomon Islands. When the U.S. found out, they sent two aircraft carrier groups and a combined Australian–American cruiser force.

On May 3–4, Japanese forces invaded Tulagi. Japanese aircraft carriers then entered the Coral Sea. Their goal was to destroy the Allied naval forces.

On May 7, both sides sent planes to attack the other's ships. The U.S. sank the Japanese light carrier Shōhō. The Japanese sank a U.S. destroyer. The next day, the Japanese carrier Shōkaku was badly damaged. The U.S. carriers Lexington and Yorktown were also damaged. Both sides lost many planes and had damaged carriers. So, the two fleets stopped fighting.

The Japanese sank more ships than the U.S. However, the Allies considered it a victory. This was because the Japanese could not capture Port Moresby or Tulagi. Also, the damaged Japanese carriers Shōkaku and Zuikaku could not fight in the Battle of Midway. This helped the U.S. win that important battle. Japan's carrier losses meant they could not invade Port Moresby by sea. Two months later, the Allies launched the Guadalcanal Campaign.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

Japan's Expansion Plans

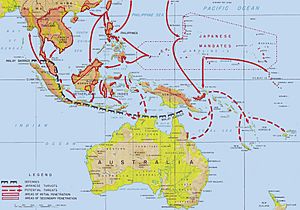

On December 7, 1941, Japan used aircraft carriers to attack the U.S. Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. This attack destroyed most of the U.S. battleships. It also started a war between the two nations. Japan wanted to destroy American navy ships. They also wanted to capture land with natural resources and gain military bases. These bases would help defend their growing empire.

At the same time as Pearl Harbor, Japan attacked Malaya. This made the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand join the U.S. as Allies against Japan. Australia had joined World War 2 in 1939 when Germany invaded Poland. Japan's war goals were to remove British and Americans from the Netherlands Indies and the Philippines.

In early 1942, Japanese forces attacked and captured many places. These included the Philippines, Thailand, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies, Wake Island, New Britain, the Gilbert Islands, and Guam. They also destroyed many Allied forces. Japan planned to use these lands to defend its empire.

Soon after the war began, Japan's Naval General Staff wanted to invade Northern Australia. This would stop Australia from being used as a base to threaten Japan's defenses.

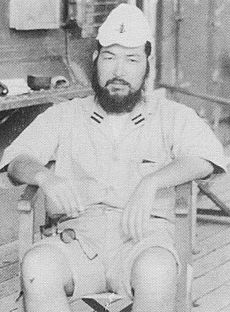

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) said it did not have enough soldiers or ships to invade Australia. Vice Admiral Shigeyoshi Inoue, who led Japan's 4th Fleet, had another idea. He wanted to capture Tulagi in the southeastern Solomon Islands and Port Moresby in New Guinea.

Capturing these places would put northern Australia within reach of Japanese planes. Japan also decided to capture New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa. This would make it hard for the United States to send supplies to Australia.

In April 1942, the Japanese army and navy made a plan called Operation MO. The plan was to invade Port Moresby by May 10. It also included capturing Tulagi on May 2–3. This would give the navy a base for attacks against Allied lands and forces.

After Operation MO, the navy planned Operation RY. This was a plan to capture Nauru and Ocean Island for their valuable phosphate deposits on May 15.

Further attacks against Fiji, Samoa, and New Caledonia were also planned. In March, Allied planes attacked Japanese naval forces invading the Lae-Salamaua area in New Guinea. Inoue then asked for aircraft carriers to provide planes. He was worried about Allied bombers from air bases in Townsville and Cooktown, Australia.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, who led Japan's Combined Fleet, was planning a big attack for June. He wanted to destroy the U.S. Navy's carriers. None of them were badly damaged at Pearl Harbor.

Getting Ready for Battle

In late April, Japanese submarines searched the areas where landings were planned. They explored Rossel Island and the Deboyne Group. They also checked the route to Port Moresby. They did not see any Allied ships.

The Japanese Port Moresby Invasion Force was led by Rear Admiral Kōsō Abe. It included 11 transport ships carrying about 5,000 soldiers. It also had one light cruiser and six destroyers. Abe's ships left Rabaul for Port Moresby on May 4. They were joined by other ships the next day. They planned to arrive at Port Moresby by May 10.

The Allied forces at Port Moresby had 5,333 men. But only half of them were soldiers. They also had poor equipment and little training.

The Tulagi Invasion Force was led by Rear Admiral Kiyohide Shima. It had two minelayers, two destroyers, six minesweepers, two subchasers, and a transport ship with about 400 troops. Supporting this force was the light carrier Shōhō, four heavy cruisers, and one destroyer. This group was led by Rear Admiral Aritomo Gotō.

Another force, led by Rear Admiral Kuninori Marumo, had two light cruisers and a seaplane tender. Inoue directed the MO operation from his cruiser.

Gotō's force left Truk on April 28. Marumo's support group left New Ireland on May 2 to set up a seaplane base. Shima's invasion force left Rabaul on April 30.

The Carrier Strike Force had carriers Zuikaku and Shōkaku, two heavy cruisers, and six destroyers. They left Truk on May 1. This force was led by Vice Admiral Takeo Takagi. Rear Admiral Chūichi Hara commanded the carrier air forces.

The Carrier Strike Force was to enter the Coral Sea south of Guadalcanal. Once there, the carriers would provide planes for the invasion forces. They would also destroy Allied planes at Port Moresby and any Allied naval forces in the Coral Sea.

Takagi's carriers tried to deliver nine Zero fighter planes to Rabaul. Bad weather stopped them twice. One Zero crashed in the ocean.

To find out if Allied naval forces were coming, the Japanese sent submarines. But Fletcher's forces got into the Coral Sea before the submarines arrived. So, the Japanese did not see them. Another submarine was attacked by Yorktown planes on May 2.

On May 1, Fletcher sent one of his task forces to refuel. The other task force finished refueling the next day. Fletcher then moved his ships northwest towards the Louisiades. He ordered another force, TF 44, to meet them on May 4. TF 44 was a joint Australia–U.S. warship force. It was led by Australian Rear Admiral John Crace. It included the cruisers HMAS Australia, Hobart, and USS Chicago.

Tulagi Invasion

Early on May 3, Shima's force arrived off Tulagi. Japanese naval troops began to take over the island. Tulagi was not defended. A small group of Australian commandos and a Royal Australian Air Force group left before Shima arrived. The Japanese forces quickly built a seaplane and communications base.

At 5:00 PM on May 3, Fletcher learned that the Japanese Tulagi invasion force had been seen. His task force, TF 17, headed towards Guadalcanal. They planned to launch air attacks against the Japanese forces at Tulagi.

On May 4, 60 planes from TF 17 launched three attacks against Shima's forces off Tulagi. Yorktown's planes sank the destroyer Kikuzuki and three minesweepers. They also damaged four other ships and destroyed four seaplanes. The Americans lost one dive bomber and two fighters. Even though the Japanese forces were hurt, they kept building the seaplane base. They started flying planes from Tulagi by May 6.

Takagi's Carrier Striking Force was north of Tulagi when they heard about Fletcher's attack on May 4. Takagi sent planes to search for the American carriers, but they found nothing.

Finding the Enemy

At 8:16 AM on May 5, TF 17 met up with other Allied forces south of Guadalcanal. At the same time, four F4F Wildcat fighter planes from Yorktown shot down a Japanese Kawanishi Type 97 plane.

A message from Pearl Harbor told Fletcher that Japan planned to land troops at Port Moresby on May 10. It also said Japanese carriers would be close to the invasion group. Fletcher planned to move his forces north towards the Louisiades.

Takagi's carrier force entered the Coral Sea early on May 6.

On May 6, Fletcher combined his forces into TF 17. He thought the Japanese carriers were still far to the north. American planes did not find the Japanese naval forces because they were beyond the planes' range.

At 10:00 AM, a Japanese flying boat from Tulagi spotted TF 17. It sent a message to its headquarters. Takagi received the report at 10:50 AM. At that time, Takagi's force was about 300 nautical miles north of Fletcher. Takagi's ships were still refueling, so he was not ready to fight. Takagi sent his two carriers with two destroyers towards TF 17. They moved at 20 knots so they could attack the next day.

American B-17 bombers from Australia attacked the Port Moresby invasion forces several times on May 6. They did not cause any damage. MacArthur's headquarters told Fletcher where the Japanese invasion forces were. MacArthur's planes saw a carrier (Shōhō) about 425 nautical miles northwest of TF 17.

At 6:00 PM, TF 17 finished fueling. Fletcher sent the oiler Neosho and a destroyer, Sims, further south. TF 17 then turned northwest towards Rossel Island. At 8:00 PM, Hara met Takagi, who had finished refueling.

Late on May 6 or early on May 7, Kamikawa Maru set up a seaplane base in the Deboyne Islands. This was to help the invasion forces as they neared Port Moresby. The rest of Marumo's force waited nearby.

Carrier Battle: Day One

Morning Attacks

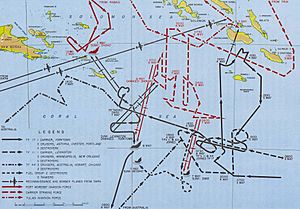

At 6:25 AM on May 7, TF 17 was 115 nautical miles south of Rossel Island. At this time, Fletcher sent Crace's cruiser and destroyer force away. This reduced the anti-aircraft defenses for Fletcher's carriers. Fletcher wanted to make sure the Japanese invasion forces could not sneak through to Port Moresby while he was fighting the Japanese carriers.

Fletcher thought Takagi's carrier force was north of his location. He told Yorktown to send 10 SBD dive bombers to search that area. Takagi launched 12 Type 97 carrier bombers at 6:00 AM to search for TF 17. Hara thought Fletcher's ships were to the south. Gotō's cruisers launched four floatplanes to search for the Americans. Both sides got their carrier attack planes ready to launch once the enemy was found.

At 7:22 AM, one of Takagi's carrier planes from Shōkaku found American ships. At 7:45 AM, the Japanese pilot reported "one carrier, one cruiser, and three destroyers." Hara thought he had found the American carriers. Hara launched all of his available planes. A total of 78 planes—18 Zero fighters, 36 Type 99 dive bombers, and 24 torpedo planes—began flying from Shōkaku and Zuikaku at 8:00 AM.

At 8:20 AM, another Japanese plane found Fletcher's actual carriers. But Takagi and Hara continued their attack on the ships to their south. They also turned their carriers northwest to get closer to the Americans. Takagi and Hara thought the U.S. carrier forces might be in two groups.

At 8:15 AM, a Yorktown plane saw Gotō's force. The pilot reported "two carriers and four heavy cruisers" 225 nautical miles northwest of TF 17. Fletcher thought he had found the main Japanese carrier force. He ordered all available carrier planes to attack. By 10:13 AM, 93 American planes were flying. These included 18 F4F Wildcats, 53 SBD dive bombers, and 22 TBD Devastator torpedo bombers. At 10:12 AM, Fletcher received a report from three United States Army B-17s. They saw an aircraft carrier, ten transports, and 16 warships.

Believing this was the main Japanese carrier force, Fletcher sent his planes towards this target.

At 9:15 AM, Takagi's force spotted Neosho and Sims. Takagi now realized the American carriers were between him and the invasion forces. Takagi ordered his planes to attack Neosho and Sims. At 11:15 AM, 36 dive bombers attacked the two American ships.

Four dive bombers attacked Sims, and the rest attacked Neosho. The destroyer was hit by three bombs. It broke in half and sank, killing all but 14 of its 192 crew members. Neosho was hit by seven bombs. Heavily damaged and without power, Neosho was sinking. Neosho radioed Fletcher that she was under attack.

The American planes spotted Shōhō at 10:40 AM and attacked. The Japanese carrier was protected by six Zeros and two Type 96 'Claude' fighters flying combat air patrol (CAP). Gotō's cruisers were around the carrier.

Lexington's air group attacked first. They hit Shōhō with two 1,000-pound bombs and five torpedoes, causing severe damage. At 11:00 AM, Yorktown's air group attacked the burning carrier with 11 more 1,000-pound bombs and two torpedoes. Torn apart, Shōhō sank at 11:35 AM. Gotō sent his warships north, but sent the destroyer Sazanami to rescue survivors. Only 203 of the carrier's 834 crew members were rescued. Three American planes were lost in the attack. All of Shōhō's planes were lost. At 12:10 PM, a pilot told TF 17 that the attack was successful.

Afternoon Events

The American planes returned and landed on their carriers by 1:38 PM. By 2:20 PM, the planes were ready to launch again. Fletcher was worried because he did not know where the other Japanese fleet carriers were. Allied forces thought that up to four Japanese carriers might be nearby. Fletcher turned TF 17 southwest.

When Inoue learned that Shōhō had been sunk, he ordered the invasion convoy to pull back north. He ordered Takagi to destroy the American carrier forces. As the invasion convoy pulled back, eight U.S. Army B-17s bombed it, but caused no damage. Gotō and Kajioka were told to place their ships south of Rossel Island for a night battle if the American ships got close enough.

At 12:40 PM, a seaplane saw Crace's force. At 1:15 PM, a plane from Rabaul also saw Crace's force. Takagi turned his carriers west at 1:30 PM. He told Inoue at 3:00 PM that the U.S. carriers were too far away to attack that day.

Inoue's men sent attack planes from Rabaul towards Crace. The first group had 12 torpedo-armed bombers. The second group had 19 Mitsubishi Type 96 planes with bombs. Both groups found and attacked Crace's ships at 2:30 PM. Crace's ships were undamaged. They shot down four Japanese planes. A short time later, three U.S. Army B-17s accidentally bombed Crace's ships, but caused no damage.

Crace radioed Fletcher that he could not complete his mission without planes. Crace moved southward. Crace's ships were low on fuel.

Takagi's staff thought that the Allied ships would be close enough to attack before nightfall. Takagi and Hara decided to attack with planes, even if they had to return after dark.

To confirm the American carriers' location, Hara sent eight torpedo bombers to search westward at 3:15 PM. The dive bombers returned from their attack on Neosho and landed. At 4:15 PM, Hara launched 12 dive bombers and 15 torpedo planes. They were ordered to find the American ships.

At 5:47 PM, TF 17 detected the Japanese forces on radar. The Americans sent 11 CAP Wildcats to attack the Japanese planes. The Wildcats shot down seven torpedo bombers and one dive bomber. They also heavily damaged another torpedo bomber. Three Wildcats were lost.

The Japanese leaders canceled the mission and returned to their carriers. The sun set at 6:30 PM. Several Japanese dive bombers found the American carriers in the darkness. They tried to land on them. Anti-aircraft fire from TF 17's destroyers sent them away. By 8:00 PM, TF 17 and Takagi were about 100 nautical miles apart. Takagi turned on his ships' searchlights to help the 18 surviving planes return.

At 3:18 PM and 5:18 PM, Neosho radioed TF 17 that she was sinking. Fletcher knew his only nearby fuel supply was gone.

As nightfall ended plane flights for the day, Fletcher ordered TF 17 to head west. Crace also turned west. Inoue told Takagi to destroy the U.S. carriers the next day. He delayed the Port Moresby landings to May 12. Takagi took his carriers 120 nautical miles north during the night. This was to protect the invasion convoy. Gotō and Kajioka could not attack the Allied warships at night.

Both sides spent the night preparing their planes for the battle. In 1972, U.S. Vice Admiral H. S. Duckworth called Coral Sea "the most confused battle area in world history." Hara said he was so frustrated with the "poor luck" the Japanese had on May 7 that he felt like quitting the navy.

Carrier Battle: Day Two

Attack on Japanese Carriers

At 6:15 AM on May 8, Hara launched seven torpedo bombers to search south of the Japanese carriers. Three Kawanishi Type 97s from Tulagi and four Type 1 bombers from Rabaul also helped in the search. At 7:00 AM, the carrier force turned southwest. They were joined by two of Gotō's cruisers, Kinugasa and Furutaka. The invasion convoy and other Japanese ships moved east of Woodlark Island.

At 6:35 AM, TF 17 launched 18 SBDs to search for Japanese ships. The skies over the American carriers were mostly clear.

At 8:20 AM, a Lexington SBD spotted the Japanese carriers and told TF 17. Two minutes later, a Shōkaku plane saw TF 17 and told Hara. The two forces were about 210 nautical miles apart. Both sides got ready to launch their planes.

At 9:15 AM, the Japanese carriers launched 18 fighters, 33 dive bombers, and 18 torpedo planes. The American carriers each launched a separate attack. Yorktown's group had six fighters, 24 dive bombers, and nine torpedo planes. Lexington's group had nine fighters, 15 dive bombers, and 12 torpedo planes. Both the American and Japanese carrier forces turned to head directly for each other.

Yorktown's dive bombers reached the Japanese carriers at 10:32 AM. At this time, Shōkaku and Zuikaku were about 10,000 yards apart. Zuikaku was hidden under clouds. The two carriers were protected by 16 CAP Zero fighters. The Yorktown dive bombers attacked Shōkaku at 10:57 AM. They hit the carrier with two 1,000-pound bombs. This caused heavy damage to the carrier's flight and hangar decks. The Yorktown torpedo planes missed with all their torpedoes. Two U.S. dive bombers and two CAP Zeros were shot down during the attack.

Lexington's planes arrived and attacked at 11:30 AM. Two dive bombers attacked Shōkaku, hitting the carrier with one 1,000-pound bomb. This caused more damage. Two other dive bombers attacked Zuikaku, but missed. The rest of Lexington's dive bombers could not find the Japanese carriers in the heavy clouds. Lexington's torpedo planes missed Shōkaku with all 11 of their torpedoes. The 13 CAP Zeros on patrol shot down three Wildcats.

Shōkaku had a heavily damaged flight deck. 223 of her crew were killed or wounded. She could not launch any more planes. At 12:10 PM, Shōkaku and two destroyers pulled back to the northeast.

Attack on U.S. Carriers

At 10:55 AM, Lexington's radar detected the Japanese planes. She sent nine Wildcats to attack them. Six of the Wildcats were too low and missed the Japanese planes as they flew overhead. Because of heavy losses the night before, the Japanese could not do a full torpedo attack on both carriers. The Japanese sent 14 torpedo planes to attack Lexington and four to attack Yorktown. A Wildcat shot down one. Eight Yorktown SBDs destroyed three. Four SBDs were shot down by Zeros protecting the torpedo planes.

The Japanese attack began at 11:13 AM. The carriers, 3,000 yards apart, fired their anti-aircraft guns. The four torpedo planes that attacked Yorktown all missed. The remaining torpedo planes hit Lexington with two Type 91 torpedoes. The first torpedo broke the aviation gasoline tanks. The second torpedo caused several boilers to stop working. Four Japanese torpedo planes were shot down by anti-aircraft fire.

The 33 Japanese dive bombers attacked after the torpedo attacks. The 19 Shōkaku dive bombers attacked Lexington. The remaining 14 attacked Yorktown. Zeros protected the dive bombers from four Lexington CAP Wildcats. The bombers damaged Lexington with two bomb hits, causing fires. These fires were put out by 12:33 PM. At 11:27 AM, Yorktown was hit in the center of her flight deck by a single 250-kilogram bomb. It went through four decks before exploding. This caused severe damage and killed or seriously wounded 66 men. Up to 12 near misses damaged Yorktown's hull below the waterline. Two dive bombers were shot down by a CAP Wildcat during the attack.

As the Japanese planes finished their attacks and flew back, U.S. planes attacked them.

After the Battle

Many damaged planes landed on their carriers between 12:50 PM and 2:30 PM. Yorktown and Lexington were both able to land planes. Forty-six of the original 69 Japanese planes returned. Three more Zeros, four dive bombers, and five torpedo planes were too damaged to repair. They were pushed into the ocean.

As TF 17 got its planes back, Fletcher thought about the situation. He knew both his carriers were hurt. He had lost many fighters. Fuel was also a problem because Neosho was gone. At 2:22 PM, Fitch told Fletcher that there were two undamaged Japanese carriers. Fletcher pulled TF 17 out of the battle. Fletcher radioed MacArthur the location of the Japanese carriers. He suggested that MacArthur attack them with bombers.

Around 2:30 PM, Hara told Takagi that only 24 Zeros, eight dive bombers, and four torpedo planes from the carriers were working. Takagi was worried about his ships' fuel levels. His cruisers were at 50% fuel, and some destroyers were as low as 20%. At 3:00 PM, Takagi said he had sunk two American carriers – Yorktown and a "Saratoga-class" carrier. Inoue called the invasion convoy back to Rabaul. He postponed Operation MO to July 3. He ordered his forces to gather northeast of the Solomons to begin Operation RY.

Zuikaku and her escorts turned towards Rabaul. Shōkaku headed for Japan.

On Lexington, an explosion killed 25 men and started a large fire. Around 2:42 PM, another large explosion happened, starting a second fire. A third explosion occurred at 3:25 PM. Lexington's crew began leaving the ship at 5:07 PM. After the carrier's survivors were rescued, the destroyer Phelps fired five torpedoes into the burning ship. It sank at 7:52 PM.

Two hundred and sixteen of the carrier's 2,951 crew members sank with the ship. 36 planes were also lost. Phelps and the other warships left to rejoin Yorktown. TF 17 moved southwest. Later that evening, MacArthur told Fletcher that eight of his B-17s had attacked the invasion convoy. He said it was moving northwest.

That evening, Crace sent Hobart, which was low on fuel, and the destroyer Walke, which had engine trouble, to Townsville. Crace remained on patrol in the Coral Sea. This was in case the Japanese invasion force tried to go towards Port Moresby.

What the Battle Meant

The Battle of the Coral Sea was the first naval battle in history where the ships never saw or fired directly at each other. Instead, planes were used to attack.

This was a carrier-versus-carrier battle. Neither commander had experience with this type of fighting. The commanders had poor communications. This was hard because the battle happened over a large area. Planes flew so fast that there was not much time to make decisions.

The Japanese had problems because Inoue was too far away at Rabaul to direct his naval forces. Fletcher was on a carrier, so it was easier for him to direct his forces. The Japanese admirals did not share information quickly.

The experienced Japanese carrier aircrews were better than those of the U.S. The Japanese aircrews caused more damage with the same number of planes. The Japanese attack on the American carriers on May 8 was better organized than the U.S. attack on the Japanese carriers.

The Japanese had much higher losses of their carrier aircrews. They lost 90 aircrew killed in the battle, compared to 35 for the Americans. Japan's highly skilled carrier aircrews could not be replaced easily. Their training programs could not produce enough new aircrew. Coral Sea was the start of Japan losing its experienced aircrews.

The Americans learned from their mistakes in the battle. They improved their carrier fighting methods. The Americans also improved their anti-aircraft defenses. Radar gave the Americans an advantage in this battle.

After Lexington was lost, Americans developed better ways to carry airplane fuel. They also found better ways to deal with damage. Coordination between the Allied land-based air forces and the U.S. Navy was poor during this battle.

Japanese and U.S. carriers would fight again in the battles of Midway, the Eastern Solomons, and the Santa Cruz Islands in 1942. They also fought in the Philippine Sea in 1944. Each of these battles affected what would happen in the Pacific War.

Battle Outcomes

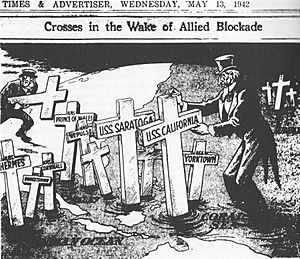

Both sides claimed victory after the battle. In terms of ships lost, the Japanese won. They sank an American fleet carrier, an oiler, and a destroyer. This was 41,826 tons of ships. The Americans sank a light carrier, a destroyer, and several smaller warships. This was 19,000 tons of ships. Lexington was one quarter of U.S. carrier strength in the Pacific. The Japanese public was told it was a victory.

The Allies won because the sea invasion of Port Moresby was stopped. This protected the supply lines between the U.S. and Australia. Even though pulling Yorktown away from the Coral Sea seemed like giving the area to the Japanese, the Japanese stopped their invasion plans.

The battle was the first time a Japanese invasion force was stopped. This improved the morale of the Allies. The Allies had been defeated by the Japanese during the first six months of the Pacific War.

Port Moresby was important to the Allies. The U.S. Navy said that the damage it did to the Japanese was greater than it really was.

The battle affected how both sides planned their next moves. Without Port Moresby in New Guinea, the Allied advance would have been harder. For the Japanese, the battle was seen as a problem. The battle showed the Japanese that Americans were not that good in battle. The Japanese thought that future carrier attacks against the U.S. would be successful.

Midway Battle Connection

One of the most important effects of the Coral Sea battle was the damage to Shōkaku and the losses to Zuikaku's air group.

Yamamoto wanted to use these carriers to fight American carriers at Midway. Shōhō was supposed to support the Japanese invasion ground forces. The Japanese thought they sank two carriers in the Coral Sea. But this still left at least two more U.S. Navy carriers, Enterprise and Hornet, which could fight at Midway.

American carriers had more planes than Japanese carriers. The U.S. also had land-based planes at Midway. This meant that the Japanese did not have more planes at Midway. The Americans would have three carriers at Midway. This was because Yorktown could still sail, even with the damage from Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy quickly repaired Yorktown at Pearl Harbor between May 27 and May 30. So, she could fight in the battle.

At Midway, Yorktown's planes were important in sinking two Japanese carriers. Yorktown also took many of the Japanese air attacks at Midway. These attacks would have been directed at the other American carriers.

The Americans worked hard to get the maximum number of forces for Midway. The Japanese did not try to include Zuikaku in the operation. The Japanese did not try to combine the Shōkaku aircrews with Zuikaku's air groups. They also did not give Zuikaku new planes. Shōkaku had a damaged flight deck. It needed three months of repair in Japan.

Historians think Yamamoto made a mistake by supporting Operation MO. Since Yamamoto thought the big battle with the Americans would be at Midway, he should not have sent fleet carriers to a less important battle like MO. Japanese naval forces were weakened at both the Coral Sea and Midway battles. This allowed the Allies to defeat them.

Yamamoto did not notice another thing about the Coral Sea battle. The Americans put their carriers in the right place and time to fight the Japanese. U.S. Navy carrier aircrews showed skill. They tried to do major damage to the Japanese carrier forces. Japan lost four fleet carriers at Midway. This made Japan start to lose the Pacific War.

Situation in the South Pacific

The Australians and U.S. forces in Australia were disappointed with the Battle of the Coral Sea. They thought that Operation MO was going to lead to an invasion of the Australian mainland. In a meeting in late May, the Australian Advisory War Council said the battle was disappointing. This was because the Allies knew about the Japanese plans.

General MacArthur told Australian Prime Minister John Curtin that Japanese forces could attack anywhere if supported by the Japanese Navy.

Because of the carrier losses at Midway, the Japanese could not invade Port Moresby from the sea. Japan then tried to capture Port Moresby by land. Japan began its attack towards Port Moresby along the Kokoda Track on July 21.

By then, the Allies sent more troops to New Guinea. The added forces slowed and stopped the Japanese advance towards Port Moresby in September 1942. They also stopped the Japanese from capturing an Allied base at Milne Bay.

The Allies tried to use their victories at Coral Sea and Midway to win the war against Japan. The Allies chose Tulagi and Guadalcanal as their first attacks.

The Japanese failure to take Port Moresby, and their defeat at Midway, meant Tulagi was not protected by other Japanese bases. Tulagi was four hours flying time from Rabaul, the nearest large Japanese base.

On August 7, 1942, 11,000 U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal. 3,000 U.S. Marines landed on Tulagi and nearby islands. The Japanese troops on Tulagi and nearby islands were killed in the Battle of Tulagi and Gavutu-Tanambogo. The U.S. Marines on Guadalcanal captured an airfield that the Japanese were building.

This started the Guadalcanal Campaign and Solomon Islands Campaigns. These led to many battles between Allied and Japanese forces over the next year. Along with the New Guinea campaign, this destroyed Japanese defenses. It caused huge losses for the Japanese military—especially the Navy. This helped the Allies win the war against Japan.

The delay in the advance of Japanese forces also allowed the United States Marine Corps to land on Funafuti on October 2, 1942. The U.S. built airfields there. From these airfields, USAAF B-24 Liberator bombers could fly. The atolls of Tuvalu were places the Allies could use to get ready for the Battle of Tarawa and the Battle of Makin. These battles started on November 20, 1943.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Batalla del mar del Coral para niños

In Spanish: Batalla del mar del Coral para niños