Port Chicago disaster facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Port Chicago disaster |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

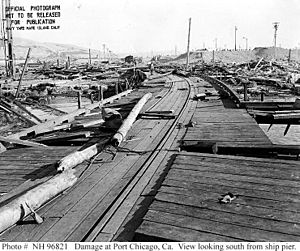

Damage at the Port Chicago Pier after the explosion of July 17, 1944 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

The Port Chicago disaster was a huge explosive accident. It happened on July 17, 1944, in Port Chicago, California, United States. A ship called the SS E. A. Bryan was being loaded with weapons for the war. Suddenly, the weapons exploded.

This terrible event killed 320 sailors and civilians. Another 390 people were hurt. Most of those who died or were injured were African American sailors.

About a month later, many sailors refused to load more weapons. They felt the conditions were too dangerous. This event is known as the Port Chicago Mutiny. Fifty men, called the "Port Chicago 50", were accused of mutiny. They were sentenced to 15 years in prison and hard work. They also faced a dishonorable discharge, meaning they would lose their Navy benefits.

Most of the 50 men were released in January 1946. Questions were raised about whether their trial was fair. Because of public pressure, the United States Navy looked at the case again. The Navy decided the men were still guilty. However, the case became famous. It helped people see the unfair treatment of African Americans. This event and other protests led the Navy to start ending segregation in its forces in February 1946.

In 1994, the Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial was built. It honors those who died in the disaster. In 2019, a new resolution was introduced in the U.S. Congress. It aims to officially clear the names of the 50 men who were accused.

Contents

What Happened Before the Explosion

Port Chicago was a town on Suisun Bay in California. This bay connects to the Pacific Ocean. In 1944, a U.S. Navy base called the Port Chicago Naval Magazine was nearby. This base was built in 1941, during World War II.

The base handled many types of weapons. These included bombs, shells, naval mines, and torpedoes. These weapons were sent to the war in the Pacific Ocean. They arrived at Port Chicago by train. Then, sailors had to load them onto cargo ships by hand and with cranes.

All the sailors who loaded weapons at Port Chicago were African American. All their leaders were white. The African American sailors had been trained for other Navy jobs. But they were made to work as stevedores, which means loading ships. None of them had been taught how to safely load ammunition.

How Sailors Were Chosen

The Navy chose African American sailors for Port Chicago from those who scored lower on tests. The Navy believed this meant they were less skilled. Officers at Port Chicago thought these sailors were unreliable. They also thought the men had trouble understanding orders.

Black petty officers led the black laborers. Some workers felt these leaders were not good at speaking up for them. They were sometimes called "slave drivers."

The commander of the Port Chicago base was Captain Merrill T. Kinne. He had no special training in loading weapons. The white officers under him also had little training.

Speed and Safety Rules

Since April 1944, officers pushed the sailors to load weapons very fast. They wanted to load 10 tons per hour per ship hatch. Most officers thought this goal was too high. Captain Kinne even kept a scoreboard. It showed which crew loaded the most. Junior officers made bets on their crews. This made them push the sailors even harder. The sailors knew about the bets. They would slow down when senior officers were watching.

There was no good system for teaching safety rules. Sailors got a few talks about safety. But no one checked if they remembered the rules. Safety rules were posted only at the pier, not in the barracks. Captain Kinne thought the sailors wouldn't understand them.

A union offered to send experienced workers to train the sailors. But the Navy said no. They worried it would cost more and slow things down. No sailor at Port Chicago ever got proper training in handling explosives. Even the officers didn't get enough training.

Winch Problems

Ships used powerful winches to lift heavy loads. A winch was used at each of the ship's five cargo holds. These winches needed constant care. Their brakes were a safety feature. They were supposed to stop a load from falling if the power failed. But skilled operators didn't use the brakes often. They could move loads faster without them. Unused brakes sometimes stopped working. The winches on the SS E. A. Bryan were steam-powered. They showed signs of wear, even though the ship was new.

On July 13, 1944, the E. A. Bryan docked. Its No. 1 winch brake was stuck "off." This meant it couldn't stop a load if power was lost. It's not clear if this brake was ever fixed. On July 15, another winch started making a loud noise. It was greased to keep it quiet. On July 17, a valve on a fourth winch needed fixing. A civilian plumber named Albert Carr fixed it. He saw a man accidentally drop a shell two feet onto the pier. It didn't explode. Carr quickly left the pier after fixing the winch. He felt the whole operation was unsafe.

Handling Weapons

The sailors were scared to work with deadly explosives. But officers told them the larger weapons were not "active." They said these weapons could not explode. They would only be made active with their fuzes when they reached the war zone.

Loading large weapons was rough work. Sailors used levers to move heavy, greasy cylinders from boxcars. They rolled them along the wooden pier. Then, they packed them into nets. Winches lifted the nets. The bundles were lowered into the ship's hold. Finally, individual weapons were dropped a short distance into place. This rough handling sometimes made damaged shells leak colored dye.

A Coast Guard officer named Commander Paul B. Cronk warned the Navy. He said the conditions were unsafe. He feared a disaster. But the Navy refused to change its ways. So, Cronk pulled his team out.

The Explosion

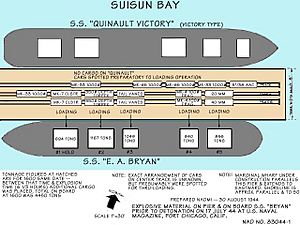

The ship SS E. A. Bryan arrived at Port Chicago on July 13, 1944. It had empty cargo holds but was full of fuel oil. Sailors began loading weapons onto it. After four days of non-stop loading, about 4,600 tons of explosives were on board. By the evening of July 17, the ship was about 40% full.

At 10 p.m. on July 17, 98 men were loading the E. A. Bryan. They were putting 1,000-pound bombs, 40mm shells, and cluster bombs into different holds. They were also loading "live" incendiary bombs. These bombs weighed 650 pounds each and had their fuzes installed. They were being loaded carefully into the hold with the possibly broken winch brake.

A new type of depth charge was also being loaded. These charges were more sensitive to bumps than other explosives. On the pier, 16 train cars held about 430 tons of explosives. In total, the weapons on the pier and in the ship were equal to about 2,000 tons of TNT.

Another ship, the SS Quinault Victory, was also at the pier. One hundred and two men were getting it ready for loading. This ship had some fuel oil that could release flammable fumes.

Sixty-seven officers and crew were on duty. There were also train crew members and a Marine guard. Nine Navy officers and 29 armed guards watched the loading. A Coast Guard fire boat was also at the pier.

At 10:18 p.m., witnesses heard a loud metallic sound. Then, a smaller explosion happened on the pier, and a fire started. Five to seven seconds later, a much bigger explosion occurred. Most of the weapons on and near the SS E. A. Bryan exploded. A huge fireball shot into the sky. It was seen for miles. An Air Force pilot said the fireball was 3 miles wide. Hot metal and burning weapons flew over 12,000 feet into the air.

The E. A. Bryan was completely destroyed. The Quinault Victory was blown out of the water and torn apart. Its back part landed upside down 500 feet away. The pier was shattered into pieces. Nearby train cars were crushed. The base buildings and much of the town were badly damaged. Broken glass and flying metal hurt many more people. No one outside the immediate pier area was killed. The U.S. government property suffered nearly $9.9 million in damage.

All 320 men on duty at the pier died instantly. Another 390 people were injured. Among the dead were all five Coast Guard members on the fire boat. African American casualties were 202 dead and 233 injured. This was 15% of all African American casualties during World War II. Navy personnel quickly worked to put out fires and prevent more explosions. Injured people were treated, and uninjured servicemen were moved to other bases.

What Happened After the Explosion

Out of 320 people who died, only 51 could be identified. Many sailors who were not hurt helped clean up and rebuild the base. Some groups of sailors were moved to other locations. The men who stayed cleaned up the pier wreckage. The sailors were very shaken. Many asked for a 30-day "survivor's leave." This leave was sometimes given to sailors who survived terrible events where friends died. But no such leaves were given to the enlisted men. White officers, however, did receive this leave. This caused a lot of anger among the sailors.

A Navy investigation started on July 21, 1944. It lasted 39 days. They interviewed officers, civilians, and enlisted men. They also questioned weapons experts. The investigation looked at many possible causes for the explosion. These included sabotage, fueling problems, ship defects, and rough handling of weapons.

The Navy decided that the speed contest between divisions was not to blame. However, the Navy's legal advisor warned that "loading explosives should never be a matter of competition." The officers in charge were found not guilty. The report said the cause of the explosion could not be determined. But it suggested that a mistake by the enlisted men was most likely the reason. The report did not mention that the men lacked training in handling explosives.

Congress decided to give each victim's family $3,000. Years later, in 1949, the families of 18 merchant seamen killed in the explosion received $390,000. In 1951, the government settled the last lawsuit related to the disaster.

A memorial ceremony for the victims was held on July 31, 1944. Admiral Carleton H. Wright spoke about the deaths. He said the base needed to keep working during the war. He gave medals for bravery to four officers and men. They had fought a fire in a train car near the pier. The bodies of 44 victims were buried at Golden Gate National Cemetery.

Admiral Wright then planned to have white sailors load ammunition in rotation with black sailors. This was the start of the Port Chicago Mutiny. Wright reported to Washington, D.C., that the men's refusal to work came from "mass fear" after the explosion. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was told about this. He was also told that white units would be added to avoid "discrimination against Negroes."

The Port Chicago Mutiny

First Actions

Sailors from Divisions Two, Four, and Eight were sent to Mare Island Naval Shipyard. This base also had an ammunition depot. On August 8, 1944, a ship docked to be loaded. The next day, 328 men were ordered to march towards the loading dock. But the entire group stopped. They refused to go on. They all said they were scared. They would not load weapons under the same officers and conditions as before. This was a mass work stoppage.

The Navy would not allow this, especially during wartime. Seventy men changed their minds after officers explained it was their duty. But 258 African American sailors still refused. They were taken under guard to a temporary military prison on a barge. This barge was meant for only 75 men. Most of these men had not been given a direct order. They were just asked if they would load ships. They all said they were afraid of another explosion. Civilian workers were called in to load the ship instead.

Among the prisoners was Seaman First Class Joseph Randolph "Joe" Small. He was asked to help keep order among the prisoners. On August 10, there were conflicts between prisoners and guards. Small saw that the prisoners were becoming rebellious. He held a meeting on the crowded barge. He told the prisoners to "knock off the horseplay" and obey the guards and officers. He said, "If we stick together, they can't do anything to us."

On August 11, 1944, the 258 men were lectured by Admiral Wright. He told them that soldiers fighting in the war needed the ammunition. He said refusing to work would be treated as mutiny. This could mean the death penalty during wartime. Wright said that while loading ammunition was risky, "death by firing squad" was worse.

After the admiral left, the men were told to split into two groups. One group would obey all orders. The other would not. All of Division Eight chose to obey. Divisions Two and Four were split. Joe Small and 43 others chose not to obey every order. These 44 were sent back to the prison. The other 214 were sent to barracks. The next morning, six more men failed to show up for work. They were also put in prison. This made a total of 50 prisoners. The Navy called these 50 men "mutineers."

Throughout August, all 258 sailors were questioned. Forty-nine of the 50 "mutineers" were held in the camp's prison. Joe Small was put in solitary confinement. Each man was interviewed by officers. Questions focused on finding "ringleaders." The men were asked to sign statements. But the written statements often didn't match what the men said. Some refused to sign. Others felt they had no choice.

After all interviews, the group of 208 men were found guilty of disobeying orders. They each lost three months' pay. Some were held as witnesses for the mutiny trial. The rest were sent to different places in the Pacific. Carl Tuggle, one of the 208, said they were given simple tasks like cleaning bathrooms. After the war, they received "bad conduct discharges." This meant they lost almost all their veterans' benefits.

The Port Chicago 50 Trial

The 50 remaining men became known as the "Port Chicago 50." In September 1944, they were formally accused of disobeying orders and committing mutiny. This was a serious crime that could lead to the death penalty or 15 years in prison.

The Navy held the trial on Yerba Buena Island. Reporters from newspapers were invited. The Navy called it the first mutiny trial of World War II. It was also the largest mass trial the Navy had ever held. Rear Admiral Hugo Wilson Osterhaus led the court. The prosecution team was led by Lieutenant Commander James F. Coakley. Six Navy lawyers defended the accused men. Lieutenant Gerald E. Veltmann led the defense team.

Veltmann and his team spoke to the accused men. They learned that not all 50 were experienced loaders. Two of the men were cooks who had never loaded ammunition. Another man had a broken wrist. Veltmann felt the men had not planned to take over from their officers. He asked for the mutiny charges to be dropped. He said the men did not try to "override superior military authority." Coakley argued that a group refusal to work was enough to be called mutiny. Admiral Osterhaus agreed with Coakley. The trial went ahead.

The Prosecution's Case

The trial started on September 14. All 50 men pleaded "not guilty." Coakley called officers as witnesses. Commander Joseph R. Tobin said he ordered six or seven men to load weapons. He said these men were willing to follow any order except loading weapons. They all said they feared another explosion. Lieutenant Ernest Delucchi, another officer, said he ordered only four of the 50 men to load weapons.

Delucchi continued his testimony. He said some men told him they would obey all orders except loading ammunition because they were afraid. He confirmed that a cook and a man with a broken wrist were among the accused. Delucchi added that the cook was prone to nervous attacks.

Later, Lieutenant Carleton Morehouse testified. He said that when problems started, he ordered each of his men to work. Ninety-six men refused at first. But all of them agreed to work after Admiral Wright's speech. None of Morehouse's men were on trial for mutiny. Morehouse confirmed that some of his men were afraid to handle ammunition. Lieutenant James E. Tobin, another officer, said 87 of his men refused to work at first. This number dropped to 22 after Admiral Wright spoke. Tobin said he put three more men in prison the next morning because they were afraid. He confirmed that one of the accused men was a cook. He was too small to safely load ammunition.

The next few days had testimony from African American sailors who were not accused of mutiny. They said there had been talk of a mass work stoppage. They also said Joe Small had spoken on the prison barge. He urged the men to obey officers and be orderly. Some said Small's speech included words about having the officers "by the tail."

Coakley finished his case on September 22. He wanted to show that a conspiracy had happened. Veltmann argued that few of the accused were directly ordered to load ammunition. He also said much of the testimony was just rumors. The court seemed to agree with Coakley on most points.

The Defense's Case

Veltmann won a small victory for the defense. He got the court to agree that an officer's testimony only applied to the men they specifically named. But reporters noticed the court was sometimes sleepy.

Starting September 23, each of the accused men testified. They generally said they would obey any order except loading ammunition. They were all afraid of another explosion. They also said no "ringleaders" forced them to refuse work. Each man said he made his own decision. They denied forcing others to refuse. Some men said they were pressured to sign false statements after questioning. Some said Joe Small did not urge a mutiny on the barge. Small himself denied saying anything like "by the balls."

Coakley tried to use the signed statements as evidence. Veltmann objected. He said the statements were forced. Coakley said they were just "admissions." The court ruled that Coakley could not use the statements as evidence. But he could ask questions based on what was in them.

Some men who were supposedly given direct orders said they never got such orders. Seaman Ollie E. Green, who had a broken wrist, said an officer only asked about his wrist.

Green told the court he was afraid to load ammunition. He said it was because officers were "racing each division to see who put on the most tonnage." He knew the way they handled ammunition, it could explode again. He said if they didn't work fast, they were threatened with prison. But when a senior officer came, they were told to slow down. This was new information for reporters. They wrote stories about it. Navy officials quickly denied Green's claims.

Another man, Seaman Alphonso McPherson, said Lieutenant Commander Coakley threatened to shoot him during questioning. McPherson stuck to his story. Coakley denied threatening anyone.

On October 9, 1944, Thurgood Marshall came to watch the trial. He was the chief lawyer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The NAACP felt this trial was very important. This was because the U.S. Navy often gave African Americans dangerous jobs with no chance to advance. Marshall was a civilian, so he couldn't officially help the defense. After hearing five men testify, Marshall spoke to the 50 men. He then talked with Veltmann's team. The next day, Marshall held a press conference. He said Coakley was handling the case unfairly. Marshall believed the men should only be tried for individual disobedience, not mass mutiny.

The defense continued. A Navy psychiatrist said the huge explosion would cause fear in everyone. A black petty officer testified that he heard no talk of conspiracy. He said it was a surprise when all the men refused to march on August 9.

Marshall held another press conference on October 17. He announced that the NAACP wanted a government investigation into the working conditions. He pointed out three things:

- The Navy's policy of putting most African Americans in segregated shore duty.

- The unsafe handling of weapons and lack of training that led to the explosion.

- How 50 men were singled out as mutineers. Their actions were not much different from the other 208 men. Marshall noted that men from Division One had refused to load ammunition before August 9. But they were just sent to other duties, not arrested.

Coakley's witnesses tried to counter this. But Veltmann showed that some accused men were not told they could refuse to make a statement. Some questioning happened with an armed guard present. Also, the officers often left out the prisoners' explanations about being afraid. They focused on things that would help Coakley's case for a conspiracy.

Final Arguments

In his closing argument, Coakley described a series of mutinous events. He said the men talked about refusing to work. This led to their mass refusal on August 9. Coakley said the mutiny continued on the barge when Joe Small spoke to the men. Coakley defined mutiny as "collective insubordination, collective disobedience of lawful orders." He said men who admitted being afraid to load ammunition during wartime were of low moral character. He thought they were likely to lie.

Veltmann denied there was a mutinous conspiracy. He said the men were in shock from the terrible explosion. He said their conversations were just them trying to understand what happened. Veltmann argued that Small's short speech was to keep order. Veltmann repeated that mutiny means trying to take over military authority. He said refusing an order was not mutiny.

The Decision and Release

On October 24, 1944, Admiral Osterhaus and the other six court members decided. After 80 minutes, they found all 50 defendants guilty of mutiny. Each man was lowered in rank. They were sentenced to 15 years of hard labor. They would also receive a dishonorable discharge.

Admiral Wright reviewed the sentences. On November 15, he reduced the sentences for 40 men. Twenty-four got 12 years, 11 got 10 years, and the five youngest got eight-year sentences. The full 15-year sentences remained for ten men, including Joe Small and Ollie Green. In late November, the 50 men were moved to a federal prison in California.

Appeals and Freedom

Thurgood Marshall began planning an appeal. He noticed that the men's complaints were not heard in court. Marshall wrote to Secretary Forrestal. He asked why only black sailors loaded weapons. He asked why they weren't trained and why they were forced to compete for speed. He also asked why they didn't get survivor's leave and why they couldn't get promoted. Forrestal gave weak answers. He said there was no discrimination because white crews loaded weapons at other bases.

Marshall started a public campaign to get the men released. In November 1944, he wrote an article for The Crisis magazine. Pamphlets were printed. Editorials against the trial appeared in African American newspapers. People started signing petitions. They demanded the mutiny verdict be overturned. Protest meetings were held. Important people were asked to help. Eleanor Roosevelt sent a copy of the NAACP's "Mutiny" pamphlet to Secretary Forrestal. She asked him to pay special attention to the case.

Marshall got permission from each of the 50 men to appeal their case. On April 3, 1945, he presented his arguments. Marshall argued that not all 50 men were given direct orders to load weapons. He said that even if orders were given, disobeying them was not mutiny. He said Coakley misled the court about the definition of "mutiny." Marshall wrote that the men were made "scapegoats." He said, "Justice can only be done in this case by a complete reversal of the findings." He also said, "I can't understand why whenever more than one Negro disobeys an order it is mutiny."

The Navy Secretary ordered Admiral Wright to look at the trials again. This time, they were told to ignore the rumors. On June 12, 1945, the court confirmed the mutiny convictions and sentences. Admiral Wright kept his reduced sentences.

After the war ended, the Navy could no longer justify such harsh sentences. In September 1945, the Navy shortened each of the 50 mutiny sentences by one year. Finally, on January 6, 1946, the Navy announced that 47 of the 50 men were being released. These 47 men were sent to active duty on Navy ships in the Pacific. They did simple tasks. Two prisoners stayed in the hospital for injuries. One was not released due to a bad conduct record. Those who had not committed other offenses were given a "general discharge under honorable conditions." The Navy gave forgiveness to about 1,700 imprisoned men at this time.

Impact of the Disaster

The Port Chicago disaster showed the unfair racial treatment in the Navy. In 1943, the U.S. Navy had over 100,000 African Americans in service. But there was not one black officer. After the disaster, the Pittsburgh Courier newspaper wrote about the event and the mutiny trial. This was part of their Double V campaign. This campaign pushed for victory over the enemy and over racial inequality at home. The mutiny trial showed the difficult race relations in the armed forces at the time.

Later in 1944, a race riot happened in Guam at a naval base. In March 1945, a group of 1,000 African American Seabees went on a hunger strike. They were protesting unfair conditions. After this, Fleet Admiral Ernest King and Secretary Forrestal worked on a plan. They wanted to fully integrate the races within the Navy. The Port Chicago disaster helped push for these new changes.

Starting in 1990, a group of U.S. congressmen tried to get the convictions overturned. But they were not successful. In 1994, the Navy refused a request to overturn the court decisions. The Navy found that racial unfairness led to the sailors' assignments. But they said no prejudice happened at the trials themselves.

In the 1990s, Freddie Meeks was one of the few Port Chicago 50 still alive. He was encouraged to ask the president for a pardon. Other men refused a pardon. They felt a pardon was for guilty people, and they believed they were not guilty. Meeks pushed for a pardon to share the story. In September 1999, 37 members of Congress supported Meeks. President Bill Clinton pardoned Meeks in December 1999. Meeks died in 2003. Efforts to clear the names of all 50 sailors have continued.

The Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial was built in 1994. It honors those who died in the explosion. The National Park Service (NPS) manages the memorial. Congressman George Miller wanted the memorial to become a national park. This would help it get more money for improvements. This effort did not change its status.

In 2006, a local newspaper wrote about an old chapel on the base. This chapel had been dedicated to the victims. It was in bad shape. A local historian noted that its stained glass windows, made in 1991, could be moved to the memorial site. In March 2008, Congress directed the NPS to manage the memorial. In July 2008, Senator Barbara Boxer introduced a bill. It would expand the memorial site by five acres. This bill did not pass. In February 2009, Miller introduced a similar bill. It also allowed the City of Concord and a park district to build a visitor center. President Barack Obama approved and signed this bill in December 2009.

The memorial is inside an active military base. Visitors need to make a reservation to visit. They are taken to the site in NPS vehicles.

Media About the Disaster

In 1990, Will Robinson and Ken Swartz made a documentary. It was called Port Chicago Mutiny—A National Tragedy. It was about the explosion and trial. They interviewed Joe Small, his lawyer, and other sailors. Danny Glover narrated the story. The documentary won an Emmy.

In 1996, Dan Collison interviewed Port Chicago sailors for a radio show. The men talked about being trained for ships but then being disappointed.

The story of the Port Chicago 50 was used for a TV movie called Mutiny. It was written by James S. Henerson and directed by Kevin Hooks. Morgan Freeman was one of the producers. The movie starred Michael Jai White, Duane Martin, and David Ramsey. It aired on NBC on March 28, 1999.

The disaster was also shown in a 2002 episode of the CBS TV show JAG.

The disaster was a big part of the 2011 novel Blue Skies Tomorrow by Sarah Sundin. One character helps the wife of an accused "mutineer" fight for justice.

In 2015, Steve Sheinkin's book The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights was a finalist for a National Book Award. The New York Times said it was good for adults too. It noted how much research Sheinkin did.

In 2017, a short documentary called Remembering Port Chicago was made. It was directed by Alexander Zane Irwin.

See also

In Spanish: Desastre de Port Chicago para niños

In Spanish: Desastre de Port Chicago para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |