School integration in the United States facts for kids

In the United States, school integration is about ending the separation of students based on their race in public and private schools. For a long time, schools were separated by race, and this is still a challenge today. During the Civil Rights Movement, making schools integrated became a very important goal.

School separation decreased a lot in the late 1960s and early 1970s. However, since 1990, it seems that schools have become more separated again. One big reason for differences in how well students do in school is the poverty rate in the schools white students and Black students attend.

Contents

- Understanding School Separation

- Fighting for Change in Court

- First Reactions to School Integration

- How Integration Happened

- School Integration Today

- Important Court Cases

- See also

Understanding School Separation

Early Steps Towards Integrated Schools

Some schools in the U.S. were integrated even before the mid-1900s. For example, Lowell High School in Massachusetts accepted students of all races from when it first opened. The first known African American student, Caroline Van Vronker, went there in 1843. Making all American schools integrated was a major reason for the Civil Rights Movement and the racial conflicts that happened in the U.S. in the second half of the 1900s.

After the Civil War, new laws were passed to give rights to African Americans. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were passed between 1865 and 1870. These amendments ended slavery, guaranteed citizenship and equal protection under the law, and stopped racial discrimination in voting. In 1868, Iowa became the first state to desegregate schools by a court order in a case called Clark v. Board of School Directors. The Iowa Supreme Court was the only court in the 1800s to say that school segregation was against the law.

The Jim Crow Era in the South

Even with these new amendments, unfair treatment continued through laws known as Jim Crow laws. These laws forced African Americans to use different park benches, drinking fountains, and train cars than white people. In 1896, the Supreme Court made a big decision in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson. They said that separate public places like schools, parks, and transportation were allowed as long as they were "equal" in quality. This idea, called "separate but equal", made school segregation legal.

Schools for Black Students

This legal separation led to the creation of black schools, which were schools just for African American children. With help from people like Julius Rosenwald and Black leaders like Booker T. Washington, these schools became important places. Teachers in these schools were highly respected leaders in their communities. However, these schools often received less money and had fewer resources compared to white schools. For example, between 1902 and 1918, a group that helped public schools gave only $2.4 million to Black schools, but $25 million to white schools.

Fighting for Change in Court

In the first half of the 1900s, there were many attempts to fight school segregation, but most were not successful. One rare success was the Berwyn School Fight in Pennsylvania, where the NAACP and Raymond Pace Alexander helped the Black community integrate local schools.

In the early 1950s, the NAACP filed lawsuits in several states to challenge school segregation. In 1954, the Supreme Court made a landmark decision in the Brown v. Board of Education case. They ruled that segregation in public schools was against the Constitution. The NAACP legal team, led by Thurgood Marshall (who later became a Supreme Court Justice), argued that separate schools were never truly equal. They said that segregated schools harmed Black students psychologically. This evidence, along with the fact that Black schools had worse facilities and paid teachers less, led to the unanimous decision.

First Reactions to School Integration

The Little Rock Nine were nine African American students who enrolled in Little Rock Central High School in 1957. The governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus, tried to stop them from entering the school. But President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent federal troops to help the students attend. After the Little Rock Nine, Arkansas saw some of the first successful school integrations in the South.

The Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision in May 1954 said that all laws creating segregated schools were unconstitutional. The NAACP then tried to enroll Black students in previously all-white schools across the South. In Little Rock, Arkansas, the school board agreed to follow the ruling. They planned a gradual integration that would start in September 1957.

By 1957, the NAACP had chosen nine Black students to attend Little Rock Central High. They were picked because of their good grades and attendance. These students were Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, Jefferson Thomas, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Minnijean Brown, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Thelma Mothershed, and Melba Pattillo Beals. One student, Minnijean Brown, was expelled for reacting to the bullying she faced. Ernest Green became the first Black student to graduate from Central High in May 1958.

When integration began on September 4, 1957, the Arkansas National Guard was called in. At first, they were ordered by the governor to stop the Black students from entering. However, President Eisenhower later ordered federal troops and the Arkansas National Guard to protect the students. They escorted the nine Black students into the school every day that year.

Challenges to Integration

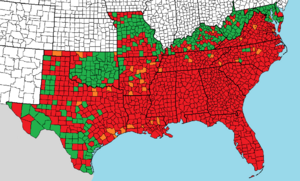

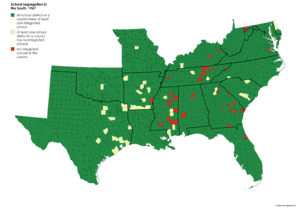

Even with the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, many people, especially in the South, were against integration. In 1955, Time magazine looked at how well Southern states were doing with desegregation. Some states like Missouri and West Virginia were doing well, while others like Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi had made no progress.

Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd declared a policy of "massive resistance". This led to nine schools in Virginia closing between 1958 and 1959. Schools in Prince Edward County, Virginia, stayed closed until 1964.

In 1956, many Southern congressmen signed a document called the Southern Manifesto. This document spoke out against racial integration in public places like schools.

In 1957, Governor Orval Faubus of Arkansas used the Arkansas National Guard to stop the Little Rock Nine from entering Central High School. President Dwight D. Eisenhower then sent federal troops to protect the students from angry white mobs. Governor Faubus even closed all of Little Rock's public high schools in 1958, but the Supreme Court ordered them to reopen later that year.

Support for Integration

Black newspapers like the Chicago Defender and the Atlanta Daily World praised the Brown decision. They saw it as a huge step for racial equality and civil rights. The decision quickly encouraged the fight for equal rights in Southern communities. Less than a year after the Brown decision, the Montgomery bus boycott began, which was another important step for African American civil rights. Today, Brown v. Board of Education is often seen as the start of the Civil Rights Movement.

By the 1960s and 70s, the Civil Rights Movement had gained a lot of support. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 made segregation and discrimination based on race illegal in public places, including schools. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 stopped racial discrimination in voting. In 1971, the Supreme Court approved the use of busing in the case of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education. Busing helped achieve desegregation even when neighborhoods were separated by race. By 1988, school integration reached its highest point, with almost 45% of Black students attending previously all-white schools.

How Integration Happened

Brown II Decision

After Brown v. Board of Education ruled that school segregation was unconstitutional, the Supreme Court discussed how to make it happen in a follow-up case called Brown II. The NAACP lawyers wanted schools to integrate right away. However, the Supreme Court gave a less clear order, saying that school districts should integrate with "all deliberate speed."

Early Integration Efforts

On August 23, 1954, 11 Black children attended school with about 480 white students in Charleston, Arkansas. The school superintendent worked with local news not to talk about it, and it went very smoothly. A similar event happened in Fayetteville, Arkansas, that same fall. The next year, the integration of schools in Hoxie, Arkansas, got national attention and faced strong opposition. While integration gave more Black students access to better-funded schools, it also sometimes led to Black teachers and administrators losing their jobs.

Opposition to integration also happened in northern cities. For example, in Massachusetts in 1963 and 1964, education activists organized boycotts to protest the Boston School Committee's failure to address racial segregation in the city's public schools.

In 1965, the first voluntary program to transfer students between city and suburban schools was started in Rochester, New York by Alice Holloway Young.

Avoiding Integration

Many white families found ways to avoid forced integration in public schools. After the Brown decision, many white families moved from cities to suburbs. They wanted to send their children to wealthier and whiter schools there. This movement is called "white flight". For example, in Houston, Texas, white students made up almost half of the school district's enrollment in 1970, but only a quarter by 1980.

Another way white families avoided integration was by taking their children out of public schools. They enrolled them in new "segregation academies" (private schools). After a 1968 Supreme Court case sped up desegregation, private school attendance in Mississippi jumped from about 23,000 students in 1968 to over 63,000 in 1970.

The issue of desegregation became more intense. In March 1970, President Richard M. Nixon said that the Brown decision was right and that he would enforce the law. He created a committee to manage the change to desegregated schools.

Even after schools integrated, many school boards still had mostly white members. This showed that structural racism could still be present.

Integration of Southern Universities

Virginia Tech 1953

In 1953, Virginia Tech became the first historically white public university in the former Confederate states to admit a Black undergraduate student, Irving L Peddrew. Three more Black students were admitted in 1954. They were all in engineering because no Black college in Virginia offered an engineering program. At that time, Virginia still had Jim Crow laws and practiced racial segregation. These first Black students at Virginia Tech were not allowed to live in dorms or eat in dining halls. They stayed with African American families in Blacksburg. In 1958, Charlie L. Yates became the first African American to graduate from Virginia Tech.

University of Louisiana at Lafayette 1954

The University of Louisiana at Lafayette was the first public college in the former Confederacy to integrate its student body. It admitted John Harold Taylor in July 1954 without any problems. By September, 80 Black students were attending, and there were no disturbances.

University of Texas System 1950-1956

The University of Texas was part of an important Supreme Court case, Sweatt v. Painter. This case led to the UT School of Law enrolling its first two Black students and the architecture school enrolling its first Black student in August 1950. The University of Texas enrolled its first Black undergraduate student in August 1956.

In 1955, Thelma Joyce White sued the University of Texas system after being rejected from Texas Western College because she was Black. The Supreme Court gave more guidance on the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Because of the lawsuit and this guidance, the University of Texas allowed Black students to enroll in Texas Western College in July 1955.

University of Georgia 1961

On January 6, 1961, a federal judge ordered Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter to be admitted to the University of Georgia. This ended 160 years of segregation at the school. The state had a law that would stop funding any school that admitted a Black student. There were rumors the school might close. On January 11, an angry crowd gathered outside Hunter's dorm, causing damage and getting media attention. Even officials who supported segregation condemned the rioters.

Georgia Tech 1961

After the University of Georgia's experience, Georgia Tech started planning how to integrate in January 1961. In May, President Edwin Harrison announced that the school would admit three Black applicants that fall. He said this decision was needed to avoid federal intervention and keep control over admissions. The decision was generally accepted in Atlanta. Ford Greene, Ralph Long Jr., and Lawrence Michael Williams, the school's first three Black students, attended classes on September 27 without any problems. This made Georgia Tech the first higher education institution in the Deep South to integrate peacefully on its own.

University of Mississippi 1962

After a speech by Governor Ross Barnett, white segregationists protested the presence of James Meredith at the University of Mississippi on September 30, 1962. Meredith had won a legal battle with the help of the NAACP to be admitted. The protests turned into riots. Two civilians died, and 160 U.S. Marshals were injured.

President John F. Kennedy sent thousands of federal troops to the campus to stop the violence and ensure James Meredith could register. Bishop Duncan M. Gray Jr., who was there, said it was a "horrible thing" but a "definite turning point." Escorted by federal marshals, U.S. Air Force veteran James Meredith registered for classes and became the first Black student to graduate in 1963.

Mercer University 1963

Mercer was the first college in the Deep South to voluntarily desegregate. On April 18, 1963, Mercer's Board of Trustees voted to accept all applicants based on their qualifications, regardless of race. This allowed Sam Oni, a 22-year-old student from Ghana, to become the first Black student at Mercer University. Sam Oni intentionally applied to Mercer to help end racial segregation in the South. He succeeded despite pressure from segregationists.

University of Alabama 1956/1963

In 1956, Autherine Lucy was able to attend the University of Alabama after a court order. For her first two days, there were no problems. But on February 6, students mobbed her, shouting hateful words. Lucy had to be driven by university officials to her next class, while being hit with rotten eggs. The police did little to stop the mobs. The university suspended Lucy "for her own protection." Lucy sued the university, but she lost the case, and the university expelled her.

In 1963, a federal court ruled that Vivian Malone and James Hood could enroll at the University of Alabama. Again, this caused conflict with the state's anti-integration laws. Governor George Wallace famously vowed to "stand in the schoolhouse door" to block Black students from enrolling. He did stand in the doorway of Foster Auditorium. Although Wallace was eventually forced by federal troops to integrate the university, he became a symbol of resistance to desegregation.

Impact on Hispanic Communities

School integration policies also affected Hispanic populations. Historically, Hispanic-Americans were legally considered white. A group of Mexican-Americans in Corpus Christi, Texas, challenged this. In Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District (1970), the court ruled that Hispanic-Americans should be classified as an ethnic minority group. This meant that integration in Corpus Christi schools needed to reflect this.

In 2005, historian Guadalupe San Miguel wrote Brown Not White. This book showed how school districts sometimes used Hispanic students to avoid truly integrating their schools. If Hispanic students were officially called "white," then a mostly African-American school and a mostly Hispanic school could be combined. This would meet integration rules, leaving white schools unchanged. The Houston Independent School District used this loophole, which hurt Hispanic students.

In the early 1970s, people in Houston protested this practice. Thousands of Hispanic students stopped attending their public schools for three weeks. In response, in September 1972, the Houston Independent School District (HISD) school board ruled that Hispanic students should be an official ethnic minority. This ended the loophole that prevented the integration of white schools.

School Integration Today

Effects on Education

Research by economist Rucker Johnson shows that school integration helped Black students who experienced it in the 1970s and 1980s. They achieved more education and earned higher wages as adults. This was before schools started to become more separated again.

For students who stayed in public schools, separation still happened in other ways, like at lunch tables or in after-school programs. Today, the practice of "tracking" in schools can also lead to separation. This is when students are placed into different classes based on their perceived ability. Often, racial and ethnic minority students are placed more often in lower-level classes, while white students are more often in advanced classes.

The focus on standardized tests is also part of the discussion about race and education. Many studies have looked at the "achievement gap", which is the difference in test scores between white and Black students. This gap got smaller until the mid-1980s, but then it stopped shrinking.

Social Benefits

In 2003, the Supreme Court said that diversity in education is important. They noted that integrated classrooms help prepare students to be good citizens and leaders in a diverse country. Psychologists have studied the social benefits of integrated schools. They found that students in integrated schools are more tolerant and accepting of others. This is compared to students who have less contact with people from different racial backgrounds.

Important Court Cases

- Roberts v. City of Boston (1850)

- Clark v Board of School Directors (1868)

- Tape v. Hurley (1885)

- Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education (1899)

- Berea College v. Kentucky (1908)

- Lum v. Rice (1927)

- Lemon Grove Incident (1931)

- Hocutt v. Wilson (1933)

- Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (1938)

- Hedgepeth and Williams v. Board of Education (1944)

- Mendez v. Westminster (1947)

- Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma (1948)

- Sweatt v. Painter (1950)

- Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (1952)

- Gebhart v. Belton (1952)

- Bolling v. Sharpe (1954)

- Briggs v. Elliott (1954)

- Lucy v. Adams (1955)

- Cooper v. Aaron (1958)

- Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (1964)

- Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education (1969)

- Brown vs Board of Education (1954)

- United States v. Montgomery County Board of Education (1969)

- Coit v. Green (1971)

- Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver (1973)

- Norwood v. Harrison (1973)

- Milliken v. Bradley (1974)

- Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler (1976)

- Runyon v. McCrary (1976)

- Bob Jones University v. United States (1983)

- Sheff v. O'Neill (1989)

- Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell (1991)

- Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 (2007)

See also

- Boston busing desegregation

- Clinton High School desegregation crisis

- Day Law

- Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974

- Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act

- List of African-American pioneers in desegregation of higher education

- Mansfield school desegregation incident

- Massive resistance

- New Orleans school desegregation crisis

- Nikole Hannah-Jones

- Ole Miss riot of 1962

- Pearsall Plan

- School segregation in the United States

- School voucher

- Segregation academy

- Separate but equal

- Southern Manifesto

- Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

- Stanley Plan

- Seattle school boycott of 1966

- The Shame of the Nation

- Tinsley Voluntary Transfer Program

- Virginia Commission on Constitutional Government

- White backlash

- Youth March for Integrated Schools (1958)

- Youth March for Integrated Schools (1959)

- Zelma Henderson, plaintiff in Brown v. Board of Education

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |