Stanley Plan facts for kids

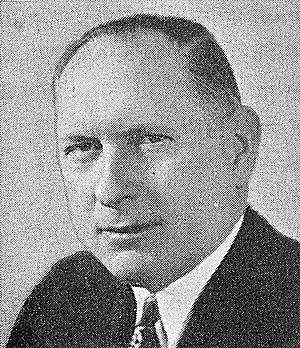

The Stanley Plan was a set of 13 laws passed in September 1956 in Virginia. These laws aimed to keep public schools separated by race, even though the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that school segregation was against the Constitution. The plan was named after Governor Thomas B. Stanley, who suggested it. It was a key part of Virginia's "massive resistance" policy against the Brown ruling, supported by U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr.. The plan also tried to limit the actions of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Virginia, as many believed the NAACP was pushing for school integration.

The Virginia Assembly passed the plan on September 22, 1956, and Governor Stanley signed it into law on September 29. However, a federal court quickly ruled part of the plan unconstitutional in January 1957. By 1960, most of the plan's main parts, including the rules against the NAACP, had been struck down by courts. Because the Stanley Plan failed, the new Governor of Virginia, J. Lindsay Almond, suggested a "passive resistance" approach to school integration in 1959. Even parts of this "passive resistance" were later ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1964 and 1968.

Contents

Why the Plan Was Created

On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court made a big decision in Brown v. Board of Education. The Court said that having separate public schools for Black and white students was unconstitutional. This ruling helped start the modern civil rights movement in America.

At first, many Virginia politicians and newspapers reacted calmly to the Brown decision. Virginia politics were mostly controlled by the Byrd Organization, led by Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr.. Leaders like Governor Thomas B. Stanley and Attorney General J. Lindsay Almond were also quiet at first.

However, James J. Kilpatrick, an editor in Richmond, Virginia, strongly opposed school integration. He pushed for Virginia to actively fight the Supreme Court's decision. This strong opposition helped convince Senator Byrd and others to take a tougher stance. On June 18, 1954, leaders from Virginia's Southside region met and decided to ask for strong state opposition to Brown. They formed a group called the Defenders of State Sovereignty and Civil Liberties. Governor Stanley, who was from the Southside, was greatly influenced by their strong views. Six days later, Governor Stanley announced he would use "every legal means" to keep schools segregated in Virginia.

The Gray Commission's Role

On August 30, 1954, Governor Stanley created a group called the Virginia Public Education Commission, led by State Senator Garland Gray. This group, often called the Gray Commission, was asked to suggest how Virginia should respond to the Brown ruling. In October 1954, another pro-segregation group, "the Defenders," formed. They demanded that state lawmakers promise not to support integration and even called for laws to stop state money from being used for desegregation. Even though they were small, the Defenders had a lot of influence in state politics.

The problem of school desegregation grew worse in 1955. On May 31, 1955, the Supreme Court, in a follow-up ruling called Brown II, ordered schools to desegregate with "all deliberate speed." Two weeks later, Governor Stanley said Virginia would continue to run its public schools separately by race. A state court ruling on November 7, 1955, also made it harder to use school vouchers (money for private schools) as a way to avoid integration.

The Gray Commission released its report just five days after this court decision. The report strongly supported segregation and criticized the Brown ruling. It suggested two main things:

- Change the state constitution to allow education vouchers for parents who did not want their children in integrated schools.

- Change state education law to let local school boards assign students based on things like skills, health, or transportation needs, but not race.

Stanley wanted to pass all the Gray Commission's ideas, except for the student assignment part. He also wanted a law that would let him stop state money from going to any public school district if it was needed for "public interest, or safety, or welfare." The plan would also let a local school district close its public schools, giving every child a voucher for a private school, or choose not to take state money.

The Push for "Massive Resistance"

Governor Stanley called the General Assembly for a special meeting on November 30, 1955. During this quick meeting, the Assembly agreed with the Gray Commission's ideas, but didn't make them law yet. They did approve a vote for January 9, 1956, to call a state meeting to change the constitution. However, some people, like Representative William M. Tuck and Senator Byrd, felt the Gray Commission's ideas were too mild. They wanted stronger action.

On January 9, Virginia voters approved the idea of a constitutional meeting by a large margin. After this, Senator Byrd and others pushed for an even stronger response. On February 1, 1956, the Virginia General Assembly passed a resolution supporting "interposition," a legal idea that a state could stand between its citizens and the federal government. On February 25, Byrd called for "massive resistance" by Southern states against the Brown ruling.

However, there were disagreements among those who supported segregation. Some wanted a more extreme approach, like closing schools, while others supported the Gray Commission's more moderate plan. This disagreement slowed down new laws. On March 6, 1956, the Virginia constitutional meeting voted to allow education vouchers. Five days later, 96 members of the U.S. Congress, led by Senator Byrd, signed the "Southern Manifesto," which criticized the Brown decision and encouraged states to "resist forced integration."

As time passed, many lawmakers worried that public education would be harmed by tuition vouchers. They also fought over whether to delay new school laws. Governor Stanley suggested a plan to stop state money from going to any school district that integrated, but this plan also failed. The regular legislative session ended on March 12, 1956, without a clear plan.

Developing the Stanley Plan

Even though there were calls for a special meeting of the legislature, Governor Stanley wasn't keen on the idea at first. But during the spring and summer, Stanley met with Senator Byrd and others to plan. Byrd was worried that if one local school district integrated, it would cause a "domino effect" across the South. Preventing this became their main concern.

Stanley called the Gray Commission back in late May 1956, but they couldn't agree on new ideas. Attorney General Almond publicly urged Stanley to call a special meeting on May 31. On June 5, Governor Stanley announced he would call the legislature for a special meeting in late August.

Stanley changed his mind because he started to agree with the "massive resistance" idea. He felt that federal courts would not compromise on segregation. Also, Senator Byrd began including Stanley in his inner group's discussions. Byrd and his allies wanted extreme measures, like closing schools, to stop integration. Stanley realized action was needed soon.

Creating the Plan's Details

Behind closed doors, the Gray Commission's executive committee secretly met on May 27. They agreed to support Stanley's earlier idea to cut off all state funds for any integrated school district. They also discussed other ideas, like student assignment plans and repealing laws that allowed school districts to be sued.

On June 11, Senator Gray gathered the seven Gray Commission members who most supported "massive resistance." They agreed to back a strong legislative plan and met with Governor Stanley that night. Stanley said he was willing "to go to any extreme" to prevent integration in Virginia.

The main ideas of the "Stanley Plan" were worked out at a secret meeting on July 2 in Washington, D.C. Those present included Byrd, Stanley, and other key leaders. They agreed on a five-point plan:

- No public school integration would be allowed in Virginia.

- School districts that integrated would lose state money.

- The state law allowing school districts to be sued would be removed.

- The power to assign students would be taken from local school boards and given to the governor.

- The governor would have the power to close any school district that integrated.

Despite often talking about local control, the real goal was to stop integration everywhere. Byrd strongly supported closing schools and helped write the other parts of the plan.

The Stanley Plan also had the support of more extreme segregationists. They wanted to remove the legal reasons for lawsuits against school districts, allow the state to take over integrated districts, and deny state funds to them.

Events soon made the issue even more divided in Virginia. On July 12, a federal judge ordered schools in Charlottesville, Virginia to integrate. On July 31, another judge ordered schools in Arlington County, Virginia to integrate. These rulings led to more lawsuits and deepened the split among pro-segregation groups.

Governor Stanley announced his plan to implement "massive resistance" on July 23, 1956. He set August 27, 1956, as the start of the General Assembly's special meeting. He made it clear that he would not allow desegregation. He stated, "There shall be no mixing of the races in the public schools, anywhere in Virginia."

Writing the Laws

The Stanley Plan caused disagreements within the Gray Commission. Attorney General Almond, who wanted to become governor, wrote a different school closing bill on July 25. He thought it was more likely to be constitutional. On July 26, Southside politicians tried to get the Gray Commission to support the Stanley Plan, but they failed. However, the commission did vote to have its lawyer, David J. Mays, write laws for both the Gray Commission's ideas and the governor's suggestions.

Mays and others worked on drafting these laws. They considered different ways to handle student assignments. On August 1, Almond told the press that a recent court decision might allow a student assignment plan that looked fair but could still keep schools segregated.

On August 6, Governor Stanley asked Almond to write a stronger version of the funding cut-off bill. This new bill would allow funds to be cut off whether a district integrated on its own or was forced to. Kenneth Patty, an Assistant Attorney General, finished this revised bill on August 13.

On August 14, Governor Stanley publicly announced that his main proposal would be to stop funds from going to any local school district that integrated. He also said he wouldn't oppose the Gray Commission's idea to assign students based on factors other than race (which might lead to some integration).

There was strong pressure on Stanley to stick to his plan. However, some wealthy districts like Arlington and Norfolk hinted they would integrate even without state funds. Outside the Southside, there wasn't much support for Stanley's plan. This led to a change in his proposals. Originally, he wanted the power to decide whether to withhold funds; now, he wanted an automatic cut-off.

The revised Stanley Plan was shown to the Gray Commission on August 22. The Commission voted 19-to-12 to drop its original ideas and support the Stanley Plan. This was a tough meeting. The Commission also approved a program to give money for tuition to students in closed school districts so they could attend private schools.

Before the special session began, it was clear that moderate and extreme segregationists were heading for a big fight. Many lawmakers were unsure about supporting the Stanley Plan. Support for the plan mostly came from the Southside and nearby areas. Many doubted if the plan would actually work or stop desegregation. Governor Stanley, however, insisted that the Assembly pass his "massive resistance" plan. He said, "If we accept admission of one Negro child into a white school, it's all over."

Passing the Stanley Plan

Other Ideas Proposed

The Stanley Plan wasn't the only idea for segregation laws during the special meeting.

- The McCue Plan, proposed by Senator Edward O. McCue, would have put all public schools under the control of the Virginia Assembly. It would have given the Assembly power over student assignments and stopped lawsuits against local school districts unless the state Attorney General started them.

- The Boothe-Dalton Plan, from Senators Armistead Boothe and Ted Dalton, suggested assigning students based on factors other than race. It included a process for parents to appeal school assignments. It also had a "local option" that would allow integration in areas that were "ready."

- The Mann-Fenwick Plan, from Delegate C. Harrison Mann and Senator Charles R. Fenwick, would have created a three-member "School Assignment Board" in each district. It also allowed any parent to protest the assignment of a new student to their school, which was meant to let white parents challenge Black students joining all-white schools.

The Special Session Begins

Governor Stanley opened the Assembly's special meeting on August 27, saying Virginia faced its "gravest problem since 1865." He said his goal was to declare that mixing races in public schools was a "clear and present danger" to an "efficient" public school system, as required by the Virginia constitution. He made it clear he wanted to stop all integration, believing that if even one school integrated, it would spread across Virginia.

Stanley explained that his plan had two main parts:

- Withholding Funds: This part would cut off funds only to parts of school districts that integrated. For example, if an elementary school integrated, funds would be cut off for all elementary schools in that district. This part of the plan would end on June 30, 1958.

- Tuition Grants: This plan offered money for tuition to parents in districts where schools closed. School districts that lost state funds would also have to provide these grants.

Fifty-eight bills about school desegregation were proposed. The Stanley Plan was debated, along with the Boothe-Dalton and McCue plans. Supporters of the Gray Commission plan also proposed bills, but they said they would support the Mann-Fenwick student assignment plan instead of their own.

The Assembly took a break and returned on September 4. Governor Stanley discussed the Stanley Plan's lack of an appeals process for student assignments. He agreed to a compromise that would allow an administrative appeal, followed by required appeals through state and lower federal courts before reaching the U.S. Supreme Court. However, the Virginia State Board of Education voted not to support the Stanley Plan, preferring the original Gray Commission plan. Former Governor Colgate W. Darden Jr. also opposed the Stanley Plan.

After the Break

By September 4, over 70 bills had been proposed. Stanley's supporters started the debate, but his political position seemed weaker. On September 6, Stanley's supporters introduced a new bill that would give the governor the power to assign students. This bill aimed to ensure "efficient" (segregated) schools and reduce danger if integration occurred. It also allowed state courts to stop school districts that broke assignment rules, setting up a conflict between state and federal courts.

From September 4 to 7, many people spoke for and against the plans. Senator Harry F. Byrd Jr. (Senator Byrd Sr.'s son) supported the Stanley Plan and said the Byrd Organization would keep making plans to stop desegregation forever if the Stanley Plan failed. Members of the NAACP and some Northern Virginia lawmakers spoke against the segregation plans.

By September 9, it was clear that the Stanley Plan only had minority support among lawmakers.

Bills Against the NAACP

On September 10, Delegate C. Harrison Mann introduced 16 bills aimed at limiting the NAACP in Virginia. Five of these bills made the state's definitions of "barratry" (stirring up lawsuits), "champerty," and "maintenance" (helping someone else's lawsuit) broader. The other eleven bills required groups that promoted or opposed laws about race, or tried to influence public opinion on behalf of any race, or raised money for legal help in racial lawsuits, to file yearly financial reports and membership lists with the state.

Compromise and Final Vote

By September 13, 17 state senators had formed a group to oppose any segregation plan that didn't allow local school districts to integrate. Facing defeat in the Senate, Governor Stanley introduced a new version of his plan on September 12. This new plan would:

- Make all local school district employees agents of the Assembly.

- Suspend any school official who assigned a Black student to a white school, making the governor the agent.

- Allow the governor to investigate assignments and ask Black students to return to their original all-Black schools.

- Allow the closure of a classroom or an entire school if integration happened.

- Give the governor power to reassign students if a school was ordered to integrate or integrated voluntarily.

- Create tuition grants to encourage Black students to leave white schools.

- Allow the governor to stop state funds from going to any school district where segregation failed.

This new plan received a lot of criticism. Some feared that only all-white schools would close. Attorney General Almond said the new plan wouldn't stop integration lawsuits and that making the governor an agent of the legislature was likely unconstitutional. Stanley later dropped this new plan and supported Speaker Moore's idea for a student assignment plan that didn't allow local integration.

On September 14, Stanley faced a setback when the House Appropriations Committee voted to allow local districts to integrate. Stanley then proposed yet another new plan. This plan would automatically cut off funds to any part of a school district that integrated. However, a school board could ask to reopen the schools, but this would mean the Assembly would take over the district, the governor would act as the Assembly's agent, and the governor would implement a segregationist student assignment plan.

Debate in the House began on September 17 and was very intense. The House passed the governor's latest proposal. In the Senate, however, the governor's proposal was changed to create a statewide student assignment board appointed by the governor. After much back-and-forth, a compromise bill was passed. It included a three-member statewide student assignment committee, and allowed appeals to go directly to the governor before state courts.

The final vote was taken at 2:00 AM on September 22. The Virginia House passed the bill 62-to-37. The Virginia Senate passed it 22-to-16.

Six "legal business" bills aimed at limiting the NAACP were also passed in the final hours. These bills were changed to address constitutional concerns. A final bill created a 10-member committee to investigate race relations and integration in Virginia.

Governor Stanley signed the school segregation and legal business bills into law on September 29, 1956. The funding cut-off and legal business bills started immediately, while the other school segregation bills took effect 90 days later.

What the Stanley Plan Did

The Stanley Plan was designed so that courts would focus on the governor or the Assembly, not local school officials. The idea was that local officials felt helpless against federal courts and feared fines or jail. It was believed that federal courts would be less likely to fine or jail the governor or the Assembly, allowing the state to effectively "interpose" itself between citizens and the federal government.

Here are the main parts of the Stanley Plan as it became law:

- Student Assignment to Keep Schools Segregated: Student assignment was no longer a local decision. A state-level three-member board, appointed by the governor, handled assignments. This board assigned students based on race and other factors, aiming to prevent mixing. Appeals went directly to the governor, and then had to go through state courts before federal courts.

- Automatic School Closures for Integration: Any school that integrated, whether voluntarily or not, had to close immediately and automatically. However, the governor could choose to take over integrated schools and reopen them as segregated schools instead of closing the entire district. A school district could also ask the governor to take over and reopen closed schools as segregated ones. The governor was also required to try to convince Black students to return to their segregated schools so that schools could reopen segregated.

- State Reassignment and Reopening of Schools: If the governor couldn't convince Black children to return to segregated schools, he could reassign them to all-Black schools. A school district could ask the governor to stop managing its public schools at any time. But if the schools reopened integrated, all state funding would be cut off. This was called the "local option."

- Funding Cut-off: State funding was automatically cut off if a school district chose the "local option" and integrated. The governor had no choice in this. The Virginia constitution required the state to run "efficient" public schools, and the legislature defined "efficient" as segregated. Funds could be cut off only to integrated elementary or secondary schools or the entire school district.

- Tuition Grants: School districts had to offer money for tuition to all students in closed schools. If schools were integrated, the district also had to offer a tuition grant to any student who didn't want to be in an integrated school. These grants could be used for non-religious education.

What Happened After the Plan

On December 25, 1956, Governor Stanley appointed members to the state Pupil Assignment Board. Just three days later, this board gave its powers to local school superintendents and boards, keeping the right to approve assignments and handle special cases.

The first legal challenge to the Stanley Plan came on January 11, 1957. A U.S. District Court ruled that the student assignment plan was unconstitutional. Over the next two years, other federal courts also struck down the student assignment law. The Pupil Assignment Board still claimed authority, causing confusion. In November 1957, J. Lindsay Almond was elected Governor. He believed "massive resistance" would fail and pushed to get rid of the statewide student assignment board. In April 1959, a new law passed that gave control over student assignments back to local school districts. The three members of the assignment board quit on February 24, 1960. On June 28, 1960, a higher court confirmed that the state student assignment board was unconstitutional. During its three years, the board made 450,000 student assignments but never allowed a Black child to attend school with white children.

The school closure part of the Stanley Plan was not challenged until it was used. No schools closed until September 1958. In August 1958, federal courts were close to ordering integration in schools in Charlottesville, Norfolk, and Warren County. On September 4, Governor Almond took away the power of local school boards and superintendents to assign students. He ordered the school boards in these three areas to refuse to assign any Black students to white schools. A day later, a federal court ordered Warren County public schools to integrate immediately. On September 11, Governor Almond closed the Warren County public school system, using the Stanley Plan's school closure rules. Charlottesville schools closed on September 17, and Norfolk schools closed on September 30. Parents of Black students immediately sued to have the school closure laws declared invalid. On January 18, 1959, the Supreme Court of Virginia ruled that the school closing law went against the Virginia constitution, which required the state to "maintain an efficient system of public free schools." On the same day, a U.S. District Court ruled that the school closing law violated the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Facing strong court opposition, Governor Almond announced a major policy change. He had hinted at abandoning "massive resistance" in September 1958. By January 1959, with even Virginia courts ruling against the state and citizens angry that their children's education was being sacrificed for segregation, Almond decided the Stanley Plan was no longer workable.

On January 28, 1959, Governor Almond told the Virginia Assembly that the state could not prevent school desegregation. He said Virginia had not "surrendered," but he would not use state police power to force schools to stay segregated. This was a clear reference to Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus using the Arkansas National Guard to stop Black students from entering Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Almond asked the legislature to repeal parts of the Stanley Plan that courts had overturned, repeal the state's compulsory school attendance law, and create a $3 million tuition grant program for students to attend segregated private schools. Almond's program became known as "passive resistance" or "freedom of choice," aiming to shift Virginia toward desegregation slowly.

On February 2, 1959, Governor Almond did not stop 17 Black students in Norfolk and four in Arlington County from peacefully enrolling in formerly all-white schools. Historians generally mark this date as the end of "massive resistance." Almond later said his time as governor was like "hell."

The End of Legal Segregation

"Passive resistance" greatly slowed down school desegregation in Virginia. New laws made it hard for often-poor Black parents to "prove" their child should be in an all-white school. By the time Almond left office in 1962, only 1% of Virginia's schools had integrated. By 1964, it was 5%.

The last parts of the Stanley Plan were removed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1964. This involved the Prince Edward County public school system. In 1951, the NAACP sued on behalf of Black children there, demanding integration. The Supreme Court combined this case, Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, with Brown v. Board of Education, and ordered Prince Edward County schools to integrate. By 1959, a second lawsuit seemed likely to force the county's schools to integrate for the 1959-1960 school year. On June 3, 1959, Prince Edward County officials voted to stop funding and close their public school system. It was the first school system in the nation to close rather than integrate. White parents then created an all-white private school. Poor Black parents could not do the same and sued to have the public schools reopened.

On January 6, 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear their case. The United States Department of Justice supported the Black parents. On May 25, 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County that Prince Edward County's school closure violated the 14th Amendment and ordered the public schools reopened immediately. The Court also struck down the tuition grants program, saying that giving grants while schools were closed violated the 14th Amendment. On June 2, the federal district court ordered the schools opened. Prince Edward County officials refused at first, but on June 17, the court threatened to imprison county officials. The officials then agreed to reopen the county's public schools on June 23, 1964.

The pace of desegregation in Virginia sped up a lot after the Griffin ruling. The federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 also helped. On May 27, 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Green v. County School Board of New Kent County that Almond's "freedom of choice" plan violated the 14th Amendment. This ruling led to the end of "passive resistance" and the integration of almost all public schools throughout the state.

The NAACP Cases

The laws aimed at limiting the NAACP, passed as part of the Stanley Plan, also did not last.

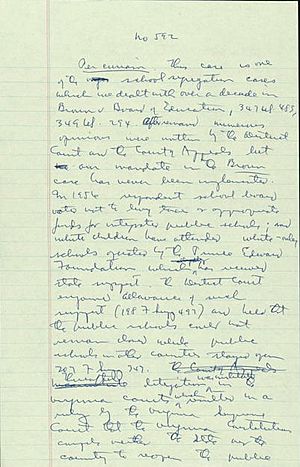

The Virginia NAACP sued in federal court in 1956 to have five laws about barratry, champerty, and maintenance thrown out. They argued these laws violated their 1st Amendment rights to freedom of speech and assembly. A federal court agreed that three laws were unconstitutional but waited for state courts to rule on the other two. Both the state and the NAACP appealed. In Harrison v. NAACP, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the federal court should have waited for state courts to decide first.

The NAACP then challenged all five laws in state court. A state court found three laws unconstitutional but upheld the barratry law and the law against encouraging lawsuits against the state. On appeal, the Virginia Supreme Court struck down the anti-advocacy law but upheld the barratry law. In a 1963 ruling, NAACP v. Button, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that all five laws violated the 1st and 14th Amendments, giving broad protection to groups that provide legal help for public interest.

The Thomson Committee

The Stanley Plan also created a committee to investigate race relations in Virginia, officially called the Virginia Committee on Law Reform and Racial Activities, but known as the "Thomson Committee" after its leader, Delegate James McIlhany Thomson. In 1957, David Scull, a printer, was subpoenaed to appear before the Thomson Committee. He was asked many questions, some not related to the committee's purpose. Scull refused to answer some questions and was found guilty of contempt of court.

Scull appealed his conviction to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a unanimous ruling in May 1959, the Court held in Scull v. Virginia ex rel. Comm. on Law Reform and Racial Activities that the conviction violated Scull's 14th Amendment rights because the committee's questions were so vague and confusing that Scull couldn't understand what he was being asked.

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |