Ole Miss riot of 1962 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ole Miss riot of 1962 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement | |||

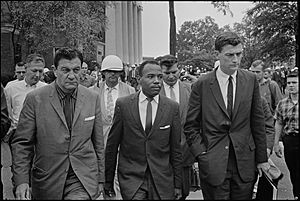

Chief U.S. Marshal James McShane (left) and Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, John Doar (right) of the Justice Department, escorting James Meredith to class at Ole Miss.

|

|||

| Date | September 30, 1962 – October 1, 1962 (2 days) | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 2 | ||

| Injuries | 300 | ||

The Ole Miss riot of 1962, also called the Battle of Oxford, was a violent event that happened on the night of September 30, 1962. It involved people who supported racial segregation. They were angry because James Meredith, an African-American veteran, was trying to enroll at the University of Mississippi (known as Ole Miss) in Oxford, Mississippi.

In 1954, the Supreme Court had ruled in a case called Brown v. Board of Education. This ruling said that separating students by race in public schools was against the law. Eight years later, James Meredith tried to attend Ole Miss. When the university found out he was African American, they tried to stop him. Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett also tried to block his enrollment.

To make sure Meredith could enroll and to prevent violence, President John F. Kennedy and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy talked with Governor Barnett. Federal and state police were sent to help Meredith register and keep order. However, a riot broke out on campus. People in the crowd attacked reporters and federal officers. They also burned property and stole vehicles. Two people, including a French journalist, died during the night. More than 300 people were hurt, including many federal officers. The riot ended when over 13,000 soldiers arrived the next morning.

After the riot, Ole Miss became desegregated. Today, a statue of James Meredith stands on campus to remember this important event. The area where the riot happened, the Lyceum-The Circle Historic District, is now a National Historic Landmark.

Contents

Why the Riot Happened

James Meredith Tries to Enroll

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in Brown v. Board of Education that separating students by race in public schools was against the law. Even after this ruling, all schools in Mississippi were still segregated. No African American students had been able to get into the University of Mississippi, or Ole Miss.

In 1961, James Meredith, an African American who had served in the Air Force, applied to Ole Miss. He chose Ole Miss because it was a very important university in the state. Meredith did not tell the university his race until he was partway through the application process. After that, state officials tried to stop him from enrolling for 20 months.

Meredith sued the university in late 1961. After many delays, the U.S. Supreme Court finally ruled on September 10, 1962. The court said that Meredith had to be admitted for the fall semester. Mississippi's Governor Ross Barnett, who supported segregation, tried another way to stop Meredith. He had the state legislature pass a law to block anyone with a "moral turpitude" charge from enrolling. This meant a charge for something considered bad behavior. Barnett then had Meredith jailed for a small mistake on a voter registration form. However, a court quickly ordered Meredith's release.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) joined the case to help Meredith. The university's board gave its power to Governor Barnett to avoid trouble. Meredith then went to the Ole Miss campus in Oxford, Mississippi to register. Governor Barnett personally blocked him. In another attempt, Meredith, along with DOJ officials, tried to register in Jackson, Mississippi. Again, Governor Barnett physically stopped him. Another try at Ole Miss was also blocked by state police.

Talks and Growing Tensions

President John F. Kennedy and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy wanted to solve the problem peacefully. They hoped to avoid sending federal troops, like what happened during the Little Rock Crisis in 1957. They were worried that a "mini-civil war" could start between federal troops and armed protesters. Robert Kennedy had many phone calls with Governor Barnett to try and find a solution.

On September 27, Governor Barnett offered to let Meredith enroll if federal marshals pretended to force him. This would make it look like he had no choice, saving his reputation in Mississippi. Kennedy refused this idea. Kennedy also wanted Barnett to promise to keep law and order. Barnett, however, believed the White House's threats of federal forces were just bluffs. Publicly, Barnett promised to keep the university segregated.

On September 28, a court ruled that Barnett was ignoring their orders. They threatened to jail him and fine him $10,000 every day if Meredith was not registered by October 2. During a football game on September 29, Barnett gave a defiant speech. He declared, "I love Mississippi! I love her people! Our customs! I love and respect our heritage!" Soon after, President Kennedy put the Mississippi National Guard under federal control.

The next day, rumors spread that federal agents were going to arrest Governor Barnett. White groups organized over 2,000 people to surround the Governor's Mansion and protect him. But no arrest happened. Many journalists came to Oxford, expecting violence at Ole Miss. They saw the story as one "solitary man against thousands."

The Riot Begins

On Sunday evening, September 30, James Meredith was flown to Oxford. He was escorted by 24 federal marshals to his dorm. Federal agents gathered on campus, supported by soldiers. They made the university's main building, the Lyceum, their headquarters. Local police set up barriers to keep out everyone except students and faculty.

In the late afternoon, Ole Miss students started gathering in front of the Lyceum. As the evening went on, more people from outside the university arrived. The crowd became very noisy and unruly. Former Major General Edwin Walker came to campus and encouraged the crowd. Earlier, Walker had asked for 10,000 volunteers to come to Ole Miss. Within an hour of Meredith's arrival, the riot had started.

As the situation got worse, the highway patrol at first helped control the crowds. But then, despite Governor Barnett's promise, police were pulled back starting around 7:25 p.m. As they left, the local and state police removed all barriers. This allowed many angry people from other states to enter the campus. The Kennedy brothers told the marshals not to shoot under any circumstances. They could only shoot if Meredith's life was in serious danger.

Violence on Campus

The crowd grew to 2,500 people and became very violent. They attacked reporters and threw Molotov cocktails (homemade firebombs) and bottles of acid at the marshals. Reporters and injured marshals, including one shot in the throat, took shelter in the Lyceum. At 7:50 p.m., chief marshal James McShane ordered his officers to fire tear gas at the crowd.

Attempts by an Ole Miss football player and a church leader to calm the crowd failed. At one point, however, Ole Miss students stopped others from taking down the American flag and raising the Confederate flag.

At 11 p.m., Governor Barnett gave a radio speech. Many thought he would try to stop the violence. Instead, Barnett encouraged the riot even more, saying, "We will never surrender!"

Rioters tried twice to drive a bulldozer into the marshals. Others took control of a fire engine. All streetlights were shot out or smashed, making it hard to see. Five cars and a mobile television unit were burned. Rioters broke into laboratories, looking for more materials to make Molotov cocktails and acid bottles.

In the darkness, rioters shot at marshals and reporters. The marshals never shot back. Several men were wounded. A marshal named Graham Same was nearly killed when a bullet hit his neck. An Associated Press reporter was shot in the back but kept reporting by phone. At 1 a.m., a sniper almost hit reporter Karl Fleming; three shots hit the Lyceum wall near his head. A car was flipped over with a reporter still inside.

Barnett had agreed to President Kennedy's request to ask state officers to return to campus, but he never did.

The crowd grew to about 3,000 people. As their behavior became more violent, the federal agents ran out of tear gas. President Kennedy had to use the Insurrection Act of 1807 and called for more soldiers in the middle of the night. These soldiers were led by Brigadier General Charles Billingslea. He ordered in U.S. Army military police and the federalized Mississippi National Guard. Navy medical staff and soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division were also sent.

Before military support arrived, white rioters found out Meredith was in Baxter Hall. They started to attack the building, possibly wanting to harm Meredith. Early in the morning, as General Billingslea's group entered the university gate, a white mob attacked his car and set it on fire. Billingslea and his aides were trapped inside the burning car. They forced the door open and crawled 200 yards under gunfire to the Lyceum Building. The Army did not shoot back.

At 1 a.m., 200 military police officers arrived. The Secretary of the Army had promised President Kennedy that soldiers would be there in two hours. But they did not arrive until five hours later. A total of 25,000 soldiers eventually came. They helped the wounded from the Lyceum and started arresting rioters. Out of 300 arrested, only about a third were Ole Miss students. General Walker was arrested and charged with trying to start a rebellion. By the end of the 15-hour riot, 166 federal agents were injured. Also, 40 federal soldiers and Mississippi National Guardsmen were wounded.

After the Riot

Two civilians died during the riots. French journalist Paul Guihard, working for Agence France-Presse (AFP), was found behind the Lyceum building with a gunshot wound in his back. Ray Gunter, a 23-year-old white jukebox repairman, had come to campus out of curiosity. He was found with a bullet wound in his forehead. Officials said these were like execution-style killings. One historian said it was a miracle that more people were not killed that night.

The day after the riot, Governor Barnett called the Department of Justice. He offered to pay for Meredith's college education anywhere outside of Mississippi. This offer was refused. On October 1, 1962, James Meredith became the first African-American student to enroll at the University of Mississippi. He attended his first class, American History. His admission was the first time a public school in Mississippi was integrated.

Later, on October 31, troops and campus police searched Baxter Hall after rumors of dynamite. They found a grenade, gasoline, and a .22-caliber rifle, among other weapons. At that time, hundreds of troops were still guarding Meredith 24 hours a day. To make local people feel better, 4,000 Black soldiers were secretly removed from the federal troops.

The total number of soldiers and forces involved in Oxford was about 30,656. This was the largest number for a single disturbance in American history.

Even though the news coverage of the Kennedys' handling of the riot was mostly positive, it made both white and Black Southerners angry. Robert Kennedy later blamed himself for not being able to prevent the riot.

The Mississippi Legislature and a local grand jury investigated the riot. They blamed the federal marshals and the Department of Justice for the violence.

What We Remember

This event is seen as a very important moment in the history of civil rights in the United States. It showed that the federal government would stand up for the law and against mob violence. It also showed support for racial justice.

One historian, Charles W. Eagles, said that James Meredith's achievement was a big victory against white supremacy. He said Meredith dealt a huge blow to white resistance against the civil rights movement. He also pushed the national government to use its power to support the fight for Black freedom.

Because of how important Meredith's admission was for civil rights, the Lyceum-The Circle Historic District where the riot happened is now a National Historic Landmark. A statue of James Meredith has been put on campus to remember his historic role. The university held programs in 2002 to mark 40 years since its integration. In 2012, they had another year of programs for the 50th anniversary. James Meredith's son also attended the university.

Several singers wrote songs about this event:

- Bob Dylan wrote "Oxford Town"

- Phil Ochs wrote "The Ballad of Oxford"

- Gene Greenblath wrote "Talking Ole Miss"

- The Chad Mitchell Trio recorded "Alma Mater"

See also

In Spanish: Disturbios en la Universidad de Misisipi de 1962 para niños

In Spanish: Disturbios en la Universidad de Misisipi de 1962 para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |