School segregation in the United States facts for kids

```wikitext

School segregation in the United States means separating students in schools based on their race. This can lead to schools where almost all students are Black or almost all are White. Today, more than half of all students in the U.S. go to schools where most students are from one racial group. About 40% of Black students attend schools where 90% or more of the students are not White. This separation is very noticeable in states like California and New York.

School segregation has a long history in the United States. Even though it's now against the law to force schools to be separated by race, many American schools are more segregated now than they were in the late 1960s. Why is this happening? Some reasons include how school zones are drawn, where people choose to live, and a Supreme Court decision in 2007. This decision made it harder for school districts to use race to try and mix schools.

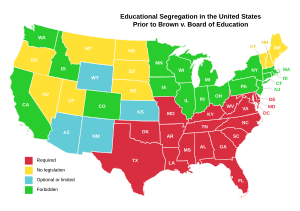

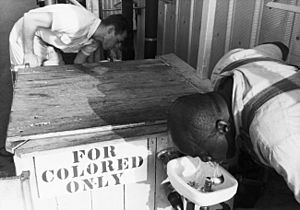

In the past, segregation was often de jure, meaning it was required by law. These laws were called Jim Crow laws and were common in the Southern U.S. They said schools had to be separate for different races but equal. However, the schools for minority students were almost never equal. After the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, which made these laws illegal, segregation became de facto. This means it happened in practice, even without laws. School segregation decreased a lot in the late 1960s and early 1970s. But since 1990, it seems to have increased again. This is partly because of where people live (Residential segregation in the United States) and how families choose schools (school choice). This separation affects how students learn and can lead to differences in success between Black and White students.

How School Segregation Started

Early Days

Even before the Civil War, there were efforts to separate students by race. In 1832, Prudence Crandall let a Black girl join her all-White school in Connecticut. People protested, and Crandall was even jailed for it. Later, in 1849, the highest court in Massachusetts said that separate schools were allowed.

After the Civil War

After the American Civil War ended slavery, new laws were passed. The Fourteenth Amendment in 1868 said everyone should have "equal protection under the law." Congress also tried to ban racial discrimination in public places. But in 1883, the Supreme Court said that private businesses could still discriminate.

Jim Crow Laws and "Separate but Equal"

Segregation became official with Jim Crow laws in the late 1800s. These laws separated Black and White people in almost all parts of public life, including schools. These laws were based on the history of slavery and unfair treatment. They said schools should be separate but equal. However, schools for Black students were almost always worse and had fewer resources.

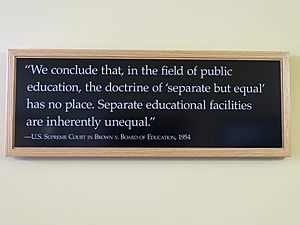

In 1896, the Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson said that "separate but equal" facilities were legal. This ruling allowed Jim Crow laws to continue for many years, even though the separate facilities were rarely equal.

The New Deal Era and Fighting Segregation

During the 1930s, government housing programs often favored White Americans. This led to Black and White neighborhoods becoming even more separate. These housing rules often meant Black neighborhoods had less access to good schools and jobs. This created more poverty and bigger gaps in how well students did in school.

In 1939, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) was created. This group worked to challenge school segregation. At first, they focused on showing that Black schools were much worse than White schools. Later, Thurgood Marshall led the LDF and played a key role in important court cases, including Brown v. Board of Education.

The Civil Rights Era and Desegregation

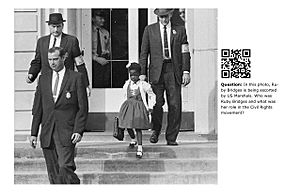

The Plessy v. Ferguson ruling was finally overturned in 1954 by Brown v. Board of Education. This Supreme Court decision made de jure (by law) segregation illegal in U.S. schools. However, many Southern states resisted this change. Schools remained mostly segregated until 1968, after new civil rights laws were passed. Some White communities even started private segregated schools to avoid integration. But later court rulings made it illegal for private schools to discriminate based on race. Desegregation efforts were strongest in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Segregation for Mexican Americans

While Black Americans faced legal segregation, Mexican Americans often experienced de facto segregation. This meant there were no federal laws forcing them into separate schools, but they were still separated from White students in practice. Local school officials often created "Mexican schools." Before the 1930s, this was rare. But after the Great Depression, some funding helped create separate schools for Mexican American children in places like Wyoming.

For example, in Oxnard, California, schools and neighborhoods were separated by ethnicity. As more Latino families moved to Oxnard, schools became crowded. Officials created "schools-within-a-school" or separate schools just for Latino students. This happened because housing rules kept Latino residents in different neighborhoods. The segregation of Mexican children happened across the U.S. West, mirroring Jim Crow laws in some ways.

Parents of both African American and Mexican American students fought against school segregation. They worked with groups like the NAACP, ACLU, and LULAC. They used lawsuits to challenge unfair policies.

Catholic and Protestant Schools

At first, Catholic schools in the South often followed the same segregation rules as public schools. But many Catholic dioceses started desegregating their schools earlier than public schools. For example, Catholic schools in St. Louis desegregated in 1947, and in Washington, D.C., in 1948.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, some states closed their public schools to protest integration. At this time, Jerry Falwell Sr. opened "Christian academies" mainly for White students.

Segregation Today

What's Happening Now?

From 1968 to 1980, schools became less segregated for Black and White students. Integration was at its highest in the 1980s. But then, it slowly started to decrease in the 1990s. By the early 2000s, many minority students were going to schools with fewer White students. Some experts call this "resegregation." Others say it's mostly because there are more minority students in general, and neighborhoods are changing.

A study in 2013 found that minority students became more isolated from White students within schools. However, school districts as a whole were statistically more integrated. Another study found that segregation increased over 25 years because of changing populations.

Why Are Schools Still Segregated?

One reason for resegregation is that schools were only required to desegregate for about five years starting in 1968. After 1980, pressure from conservatives led to court rulings like Freeman v. Pitts. This ruling made it easier for schools to stop desegregation efforts. Today, segregation between different school districts is a problem because of the Milliken v. Bradley ruling. This ruling stopped forced desegregation across district lines.

Another reason is "white flight." This happens when White families move their children to schools with fewer minority students. This was seen in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when White student numbers dropped in highly desegregated districts.

Today, school zoning, housing rules, and school choice are big reasons for segregation. This separation is not just by race but also by how much money families have. Wealthier families can often afford to move to areas with better schools. Even within integrated schools, advanced classes like AP or Honors programs often have more White students. Some studies show that White students might choose these advanced classes to have less contact with minority students, even in integrated schools.

Where People Live Matters

Neighborhood Segregation

A main reason for school segregation is that neighborhoods are still very separate by race (Residential segregation in the United States). Since schools are often local, where you live often decides which school you go to. Neighborhood segregation is also linked to differences in income.

Many policies from the mid-1900s, like certain housing loans and highway projects, led to "white flight" and the growth of suburbs. This meant money and services moved away from cities, hurting poor city residents. City schools then became a clear example of how much educational opportunities differed for students of color.

A study found that from 1990 to 2000, neighborhood segregation decreased a little, but school segregation increased. This means that local policies were no longer helping to mix students as much as before.

In 2005, a study showed that over 80% of schools with mostly minority students (over 90% non-White) were also high-poverty schools. This means students in these schools often face challenges like not having enough food or stable housing. These factors make it harder to learn effectively.

Experts say that many students of color in inner-city neighborhoods are not prepared for higher education because of these barriers. They also note that schools with many minority students often have fewer financial resources.

Supreme Court Decisions

While Brown v. Board of Education started desegregation, later Supreme Court rulings made it harder. The 1970 ruling in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education supported busing to mix students within a school district. But it didn't help with segregation between different school districts. The 1974 ruling in Milliken v. Bradley stopped forced busing across district lines.

In 1990, Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell said that once a school district had tried hard to desegregate, it could be released from court supervision. This allowed schools to end desegregation efforts, even if segregation was likely to return. A 2012 study found that segregation levels increased gradually after districts were released from court oversight. This shows that court orders were effective but their effects faded without continued supervision.

In 2007, two rulings (Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 and Meredith v. Jefferson County Board of Education) limited how schools could use race in assigning students. The Court said that plans trying to make schools reflect the district's racial makeup were not allowed if there were other ways to achieve the goal.

School Choice

School choice allows students to attend schools outside their local zone. While this could help mix students, it often does the opposite. Studies show that charter schools often keep or even increase existing racial and economic segregation. Students often leave more diverse public schools for less diverse charter schools.

Private schools also play a role. In the South, more White students enrolled in private schools in the 1970s and 1990s. This contributed to ongoing school segregation.

However, magnet schools generally help with racial integration. They were created as an alternative to busing and aimed to bring together diverse students. Even today, magnet schools are usually more racially mixed than other school choice options.

Ideas About Race in Society

Some experts, like Jerry Roziek, argue that to solve school segregation, we need to deal with racism itself, not just things like school choice or housing rules. He says that society often ignores the negative effects of segregation because of racism. He mentions Derrick Bell's critical race theory, which suggests that racism will always be present in the U.S. This idea means that ending desegregation orders was based on a false belief that communities were becoming less racist, which then led to more segregation.

Another idea is anti-Blackness theory, which says that Black people are seen as outside of Western human rights. Michael Dumas suggests that understanding this theory can help teachers support Black children everywhere. Ta-Nehisi Coates, in his book Between the World and Me, writes about living as a Black person in a world shaped by harsh racism, where racism is a major barrier to progress.

What Happens Because of Segregation?

Education and Learning

The level of racial segregation in schools greatly affects how well minority students do in school. When schools became more integrated in the 1970s and 1980s, Black students made big academic gains. Their high school dropout rates went down, and the gap in test scores between Black and White students got smaller. They also had better outcomes later in life, like higher earnings and less chance of being in prison.

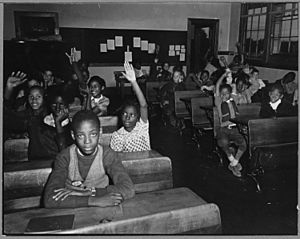

Today, minority students are often in high-poverty, low-achieving schools. White students are more likely to be in high-achieving, wealthier schools. Schools with many minority students often have less experienced teachers, high teacher turnover, and fewer resources like good facilities and learning materials. They also tend to have less challenging classes and fewer AP courses.

It's not just about resources. The mix of students itself can affect learning. A 2009 study found that attending a school with many Black students negatively affected Black students' academic success, even when other factors were considered.

Federal policies like the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) tried to address differences in learning by using standardized tests. But schools labeled as "failures" under NCLB were usually high-poverty schools in segregated areas. These policies didn't fix the root problems that created these segregated schools.

Social Well-being

Research on school integration shows both short-term and long-term benefits for students. Integration has a small but good impact on how Black students do in school in the short term. It has a very clear positive impact on their long-term success, like how much education they get and their earnings.

Integrated education helps students make friends across different races and accept cultural differences. It also reduces racial fears and prejudice in both minority and White students. Students who go to integrated schools are more likely to live in diverse neighborhoods as adults.

Money and Jobs

In the long run, integration is linked to better education and job success for all ethnic groups. It also leads to better relationships between groups, a higher chance of living and working in diverse places, and less involvement with the justice system.

A 2014 study showed that as school segregation increases, economic differences based on race also increase. Schools with mostly minority students often have fewer resources and lower academic abilities because they are in areas with less wealth.

A 1994 study found that contact between races in elementary or high school positively affects long-term success for Black communities. Black people who went to desegregated schools were more likely to aim for better jobs, go to diverse colleges, have diverse friends and professional connections, and get professional jobs. In schools where students come from wealthier families, students often do better because they feel safer.

High school dropout rates are much higher in urban schools than in suburban ones. Many dropouts are from impoverished, urban, non-White schools. In 2000, about half of high school dropouts were employed, but they earned much less than the national average. College graduates earned much more.

Black Teachers

One sad result of desegregation after Brown v. Board of Education was a huge loss of Black teachers. These teachers have not returned to schools in large numbers. This means there are fewer Black teachers, even though the student population is becoming more diverse. Experts say that while the ruling aimed to integrate students, it didn't protect Black teachers, leading to the loss of many community-supported schools and the teachers who worked there.

Ideas for the Future

Even though the Supreme Court limited how schools can use race in student assignments, they didn't ban it completely. Schools can still consider race when choosing locations for new schools, drawing attendance zones, giving out resources for special programs, and recruiting diverse students and teachers. They can also use income-based policies to try and achieve racial integration indirectly, but this doesn't always work well.

Some experts believe that since court rulings are strict and neighborhoods are still segregated, efforts should focus on making neighborhoods less segregated. This could involve better enforcement of the Fair Housing Act and changing rules that limit housing options. Policy could also set aside affordable housing in new communities that have good school districts.

For school choice, policies could make sure that charter schools recruit diverse students and teachers, provide transportation for poorer students, and have a racial mix similar to public schools. Expanding magnet schools, which were created to help desegregate, could also lead to more integration, especially if they can draw students from different areas. Another idea is to have school districts cover larger areas, like counties, so students can come from more diverse places.

Some scholars argue that policies should focus on mixing students by economic status rather than just race. They say that a school's overall economic status is what really affects how well students learn. However, other experts argue that the original goal of desegregation was to give Black students better access to important opportunities, which affects their lives in the long run, not just their test scores. ```

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |