Prudence Crandall facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Prudence Crandall

|

|

|---|---|

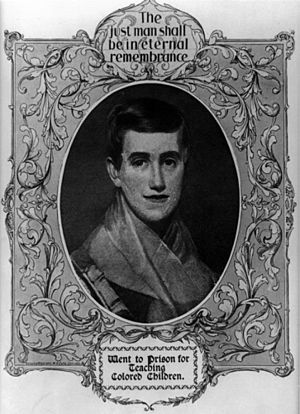

Crandall, 1834 portrait by Francis Alexander

|

|

| Born | September 3, 1803 |

| Died | January 28, 1890 (aged 86) |

| Education | Black Hill Quaker School |

| Alma mater | Moses Brown School |

| Occupation | Teacher |

| Known for | Canterbury Female Boarding School |

| Spouse(s) | Calvin Philleo |

| Parent(s) | Pardon Crandall and Esther Carpenter Crandall |

| Awards | State heroine of Connecticut |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | Canterbury Female Boarding School |

| Signature | |

Prudence Crandall (born September 3, 1803 – died January 27, 1890) was an American schoolteacher and activist. She is famous for running the first school for African-American girls in the United States. This school was located in Canterbury, Connecticut.

In 1832, Crandall allowed Sarah Harris, a 20-year-old African-American student, to join her school. This made it the first integrated classroom in the United States. When white parents found out, they started taking their children out of the school. Prudence Crandall was a very determined person. Instead of asking Sarah Harris to leave, she decided to teach only African-American girls.

Her decision led to a lot of trouble. She was arrested and even spent a night in jail. The people in the town became violent, and she was eventually forced to close her school. She left Connecticut and never lived there again. Years later, the state of Connecticut honored her. In 1995, she was named the Official Heroine of Connecticut.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Prudence Crandall was born on September 3, 1803. Her parents, Pardon and Esther Carpenter Crandall, were Quakers. They lived in Carpenter's Mills, Rhode Island. When Prudence was about 10, her family moved to Canterbury, Connecticut.

Her father did not think much of the local public school. So, he paid for her to attend the Black Hill Quaker School in Plainfield. Her teacher there, Rowland Greene, was against slavery. He believed that black people needed education.

When she was 22, Prudence attended a Quaker boarding school in Providence, Rhode Island. This school was later renamed the Moses Brown School. After finishing her studies, Prudence Crandall taught at a school in Plainfield. She became a Baptist in 1830.

Starting the Boarding School

In 1831, Prudence Crandall bought a house with her sister, Almira Crandall. They wanted to start the Canterbury Female Boarding School. Important people in Canterbury asked them to open this school to educate young girls in the town.

With help from her sister and a maid, Prudence taught about forty students. They learned subjects like geography, history, grammar, arithmetic, reading, and writing. Prudence Crandall was a successful principal. The school did very well until September 1832.

Integrating the School

Prudence Crandall grew up as a Quaker in the North. However, she did not know many black people or abolitionists at first. She learned about the problems faced by black people from an anti-slavery newspaper called The Liberator. Her housekeeper, a young black woman, told her about it.

After reading the newspaper, Prudence Crandall wanted to help people of color. Her chance came in the fall of 1832. Sarah Harris, whose father was a free African-American farmer, asked to join the school. Sarah wanted to become a teacher for other African Americans.

Prudence Crandall accepted Sarah Harris into her school. This made it the first integrated school in the United States. However, important townspeople did not like this. They pressured Crandall to make Sarah leave, but Prudence refused. Even though the white students did not openly object, their families took them out of the school.

Because of this, Crandall decided to teach only African-American girls. She went to Boston to talk with abolitionists Samuel J. May and William Lloyd Garrison. They supported her idea. She temporarily closed the school to find new students of color. On March 2, 1833, Garrison put advertisements for new students in his newspaper, The Liberator.

Crandall announced that her school would open on April 1, 1833. It would be "for the reception of young Ladies and little Misses of color." The cost was $25 per quarter. On April 1, 1833, twenty African-American girls arrived. They came from cities like Boston, Providence, New York, Philadelphia, and areas in Connecticut.

Public Opposition and Legal Challenges

The townspeople strongly opposed Crandall's school for black girls. Andrew Judson, a lawyer and politician in Canterbury, led the opposition. He believed that black people were an "inferior race" and should not be seen as equal to white people. He also thought that black people should be sent to Africa. Judson predicted that the town would be ruined if Crandall's school succeeded.

A group of white men from the town tried to convince Crandall to close her school. They claimed it would be dangerous for white people. One man said the school would encourage "social equality and intermarriage of whites and blacks." Crandall simply replied, "Moses had a black wife."

At first, citizens protested the school. Then, they held town meetings to stop it. The town's actions grew into threats and violence against the school. Crandall faced strong local opposition, and her opponents did not give up.

On May 24, 1833, the Connecticut legislature passed a "Black Law." This law made it illegal for a school to teach African-American students from outside the state without town permission. In July, Crandall was arrested. She was put in the county jail for one night. She refused to pay bail because she wanted the public to know she was jailed. A Vermont newspaper even wrote about it with the headline "Shame on Connecticut." The next day, she was released on bond to wait for her trial.

Under the Black Law, the townspeople refused to help Crandall or her students. They closed their shops and meeting houses to them. Stage drivers would not give them rides, and doctors refused to treat them. Townspeople even poisoned the school's well, which was their only water source. They also stopped Crandall from getting water from other places. Crandall and her students faced extreme difficulties. Her father was also insulted and threatened. Despite all this, Crandall continued to teach the young women of color. This made the community even angrier.

One of Crandall's students, 17-year-old Ann Eliza Hammond, was also arrested. However, with help from abolitionist Samuel J. May, she was able to get bail. About $10,000 was raised to help the school.

Court Cases and School Closure

Arthur Tappan of New York, a leading abolitionist, gave $10,000. This money was used to hire the best lawyers to defend Crandall. The first trial began on August 23, 1833. The case questioned if the Connecticut law against educating African Americans from outside the state was constitutional.

The defense lawyers argued that African Americans were citizens in other states. Therefore, they should be considered citizens in Connecticut too. They focused on how the law took away the rights of African-American students under the United States Constitution. The prosecution, however, said that freed African Americans were not citizens in any state. The jury in the county court could not agree on a decision.

A second trial in Superior Court ruled against the school. The case then went to the Supreme Court of Errors (now called the Connecticut Supreme Court) in July 1834. The Connecticut high court overturned the lower court's decision on July 22. They dismissed the case because of a small mistake in the legal process. The Black Law said that schools needed permission from local officials to teach black children from outside Connecticut. But the charges against Crandall did not say that she had started her school without this permission. So, the Supreme Court said the charges were wrong because they did not describe a crime. The Court did not decide whether free African Americans had to be recognized as citizens in every state.

The court cases did not stop the school from operating. But the townspeople's attacks on the school increased. The residents of Canterbury were so angry that the court dismissed the case that they tried to burn the school in January 1834. They failed to destroy it. On September 9, 1834, a group of townspeople broke almost ninety windowpanes using heavy iron bars. For the safety of her students, her family, and herself, Prudence Crandall closed her school on September 10, 1834. Connecticut officially removed the Black Law in 1838.

Later Life and Recognition

In April 1834, supporters of Prudence Crandall asked Francis Alexander to paint her portrait. She had to go to Boston for the sittings. There, she became the center of attention at abolitionist parties. People in Boston honored her as a true hero for the anti-slavery cause.

In August 1834, Crandall married Rev. Calvin Philleo, a Baptist minister. The couple moved away from Canterbury. They lived in Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island, and Illinois. Crandall also became involved in the women's suffrage movement, which fought for women's right to vote. She ran a school in LaSalle County, Illinois. She separated from Philleo in 1842, and he died in 1874.

After her husband's death, Crandall moved to Elk Falls, Kansas, around 1877, with her brother Hezekiah. Hezekiah died there in 1881.

In 1886, the state of Connecticut honored Prudence Crandall. With support from writer Mark Twain, the legislature gave her a $400 annual pension (which is like equivalent to $13,000 in 2022 today). Prudence Crandall died in Kansas on January 28, 1890, at the age of 86. She is buried in Elk Falls Cemetery with her brother Hezekiah.

Prudence Crandall's Brother Reuben

Prudence's younger brother, Reuben, was a doctor and a botany expert. He was not an abolitionist and did not support Prudence's efforts to educate African-American girls.

Reuben was arrested on August 10, 1835, in Washington, D.C. He was accused of trying to cause rebellion and publishing anti-slavery writings. He was jailed for 8 months before his trial. This was the first trial for sedition (trying to cause rebellion) in the country's history. It attracted many people, including members of Congress. Francis Scott Key, who wrote "The Star-Spangled Banner," was the prosecutor. The jury found Reuben not guilty of all charges. This was a big embarrassment for Key and ended his political career. Sadly, Reuben caught tuberculosis while in jail and died soon after.

Legacy and Honors

Prudence Crandall's bravery and efforts were recognized in many ways, especially in the late 20th century.

- In 1965, the NBC television series Profiles in Courage aired an episode about her.

- The Prudence Crandall House in Canterbury was bought by the State of Connecticut in 1969. It is now a state museum and was named a National Historic Landmark in 1991.

- In 1973, the Prudence Crandall Center for Women was founded in New Britain, Connecticut. It helps victims of domestic violence.

- Crandall was the subject of a Walt Disney/NBC television movie called She Stood Alone (1991). Actress Mare Winningham played her.

- In 1994, Crandall was added to the Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame.

- In 1995, the Connecticut General Assembly officially named Prudence Crandall the state's heroine.

- The Prudence Crandall Elementary School in Enfield, Connecticut, opened in 1966.

- In 2001, Crandall was added to the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame.

- In 2008, a statue of Crandall and a student was put up in the Connecticut state capital.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Prudence Crandall para niños

In Spanish: Prudence Crandall para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |