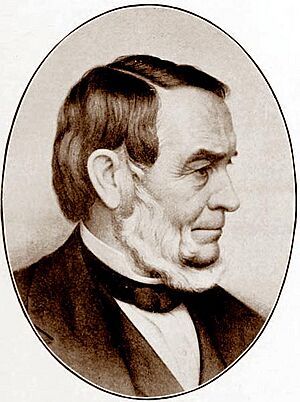

Samuel Joseph May facts for kids

Samuel Joseph May (born September 12, 1797 – died July 1, 1871) was an important American reformer in the 1800s. He strongly supported better education, equal rights for women, and ending slavery. May believed that people's rights were more important than owning property. He also spoke up for minimum wages and suggested limits on how much wealth one person could gather.

He was born into a wealthy family in Boston on September 12, 1797. His father, Joseph May, was a merchant. His mother, Dorothy Sewell, came from famous families in colonial Massachusetts. Samuel Joseph May's sister was Abby May Alcott, who was the mother of the famous writer Louisa May Alcott. In 1825, he married Lucretia Flagge Coffin. They had five children together.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Samuel Joseph May grew up in Boston, Massachusetts. When he was four, his older brother Edward died in an accident. May later said this sad event made him want to help fix the world's problems.

He started attending Harvard when he was 15, in 1813. During his time there, he decided to become a minister. He also taught school in Concord, Massachusetts. Here, he met many important Unitarian thinkers and activists. One person, Noah Worcester, taught him about peaceful ways to oppose things.

May finished his studies at Harvard Divinity School in 1820. He then became a Unitarian minister. He accepted a job in Brooklyn, Connecticut, where he was the only Unitarian minister in the state. He became well-known in New England for trying to make changes and start new Unitarian churches.

In 1825, he married Lucretia Flagge Coffin. They had five children. Their first son, Joseph, died young. They later named another son Joseph, in honor of him and May's father.

Early Efforts for Change

May started a newspaper called The Liberal Christian in 1823. Its main goal was to explain the Unitarian faith. In 1826, he helped create the Windham County Peace Society. He also organized a meeting in 1827 to improve schools in Connecticut. He began giving lectures on these topics in 1828.

May was a pacifist, meaning he believed in peace and not using violence. He helped start peace groups and spoke against the death penalty. He also believed in "nonresistance," which meant not fighting back, even to defend himself.

He became a leader in the temperance movement, which worked to reduce alcohol use. He saw people addicted to alcohol as "slaves" to drink. May was perhaps most famous for his work in education. He wanted to make public elementary schools better. He believed schools should include all races and both boys and girls. He also supported the ideas of Swiss educator Johann Pestalozzi. May tutored his sister Abigail May in philosophy. He wrote to her that "universal education" was very important for developing the mind.

Fighting to End Slavery

In 1830, May met and became good friends with William Lloyd Garrison. This friendship led him to join the abolitionist movement, which worked to end slavery. Even though his views on slavery upset his family and friends, he stuck to his beliefs.

He helped Garrison start several important groups, including the New England Anti-Slavery Society and the American Anti-Slavery Society. He also worked for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. He helped write rules for these groups and traveled to give speeches.

May fought for equal rights for all races and better schools. In the 1830s, he helped Prudence Crandall. She ran a school for African American girls in Canterbury, Connecticut. Local residents and the state government tried to stop her. This experience made May stop supporting the American Colonization Society, which aimed to send free Black people to Africa.

In 1840, May was one of the American delegates who went to the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London.

In 1845, May became the pastor of the Unitarian Church of the Messiah in Syracuse, New York. He stayed there until 1868. He strongly opposed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This law required people to help return escaped slaves. May would announce in his sermons when escaped slaves were in the area. He would collect money to help them. He also helped many escaped slaves on the Underground Railroad.

May also fought for equality for free Black people in his churches. He allowed them to sit in the front rows, instead of being separated in the back. These actions sometimes led to white church members criticizing him. In the late 1850s, and after Abraham Lincoln became president, May faced strong opposition. People sometimes attacked him or burned his image in protest.

Working for Women's Rights

Besides speaking and writing about ending slavery, May was a strong supporter of women's rights. He especially pushed for women to have the right to vote. In 1846, he wrote an important paper called The Rights and Condition of Women. In it, he argued for women to have equal rights in all parts of life.

His work for women's rights also led him to believe in sharing the nation's wealth more fairly. He thought the legal system needed big changes. He also suggested a "soak-the-rich" income tax, meaning higher taxes for wealthy people. He wrote other books too, including "Education of the Faculties" (1846) and "Recollections of the Anti-Slavery Conflict" (1868).

Later Years and Lasting Impact

By the time of the American Civil War, May was torn. He believed in peace, but he also felt that slavery might only end through fighting. He thought using force against the Southern states was needed. After the war ended and slavery was abolished, May continued his work. He fought for racial, economic, and educational equality until he died. He even served as president of the Syracuse public school district.

Samuel Joseph May passed away on July 1, 1871, in Syracuse, New York. He is buried at Oakwood Cemetery in Syracuse.

The May Pamphlet Collection

In 1870, May gave a collection of over 10,000 documents to the Cornell University Library. These included pamphlets and other papers about the anti-slavery movement. Other abolitionists asked for more donations to the collection. They wanted the history of the anti-slavery movement to be saved. This way, future generations would understand the goals of the abolitionists.

In 1999, the Cornell University Library received a grant to organize and digitize the collection. This work is now finished, and the collection is available online.

His Legacy

In 1885, the Unitarian Church of the Messiah in Syracuse was renamed in May's honor. It became the May Memorial Unitarian Church. Today, it is known as the May Memorial Unitarian Universalist Society (MMUUS).