Raymond Pace Alexander facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Raymond Pace Alexander

|

|

|---|---|

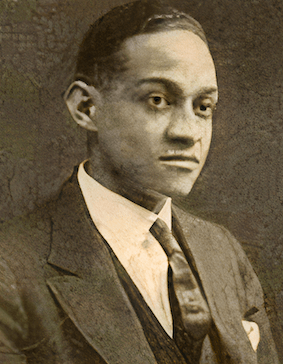

Raymond Pace Alexander in 1943

|

|

| Member of the Philadelphia City Council from the 5th district |

|

| In office January 7, 1952 – January 5, 1959 |

|

| Preceded by | Eugene J. Sullivan |

| Succeeded by | Thomas McIntosh |

| Judge of the Pennsylvania Court of Common Pleas No. 4 | |

| In office January 5, 1959 – November 1974 |

|

| Preceded by | John Morgan Davis |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Raymond Pace Alexander

October 13, 1897 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | November 24, 1974 (aged 77) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (1937–1940, after 1947) |

| Other political affiliations |

Republican (before 1937, 1940–1947) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Education |

|

| Occupation |

|

Raymond Pace Alexander (born October 13, 1897 – died November 24, 1974) was an important American leader. He was a lawyer, politician, and a judge. He is known for being the first African American judge appointed to the Pennsylvania Court of Common Pleas.

Born and raised in Philadelphia, Raymond Pace Alexander achieved many firsts. In 1920, he was the first Black person to graduate from the Wharton School of Business. After finishing Harvard Law School in 1923, he became a leading civil rights lawyer in Philadelphia. He became famous for fighting for equal rights. This included a big case about school segregation in Berwyn, Pennsylvania. He also represented Black people in other important cases, like the Trenton Six.

Alexander became involved in politics, first trying to become a judge in the 1930s. In 1949, President Harry S. Truman considered him for a high court position. He finally won a seat on the Philadelphia City Council in 1951. After serving two terms, he was appointed as a judge. He was re-elected as a judge in 1959. Throughout his career, he worked hard for racial equality. He retired in 1969 and passed away in 1974. Today, a special professorship at the University of Pennsylvania honors his work.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Raymond Pace Alexander was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on October 13, 1897. His parents were working-class Black Americans. Like many others in the 1800s, they had moved from the South. They sought better jobs and to escape harsh segregation there. His father, Hillard Boone Alexander, was born into slavery in Mecklenburg County, Virginia. His mother, Virginia Pace, was also born into slavery in Essex County, Virginia. They married in Philadelphia in 1882.

The Alexander family lived in the Seventh Ward of Philadelphia. This area is now called Center City, Philadelphia. Raymond's father and uncle taught horseback riding to wealthy people. But by 1915, cars became popular, and their business failed.

In 1909, Raymond's mother passed away from pneumonia. Raymond started working right away to help his family. His father sent Raymond and his three siblings, including his sister Virginia, to live with their aunt and uncle. They lived in North Philadelphia. Raymond continued to work through grade school and high school. He worked on docks, sold newspapers, and ran a shoe-shining stand. He also worked at the Metropolitan Opera House for six years. He said this job "opened a new world" for him.

Alexander attended Central High School. He graduated in 1917 and gave a speech at his graduation. He then went to the University of Pennsylvania on a scholarship. In 1920, he became the first Black graduate of the Wharton School of Business. He then went to Harvard Law School. To pay for school, he worked as a teaching assistant. In the summers, he took classes at Columbia University. He also worked as a porter for a railroad company. While still in law school, Alexander filed his first lawsuit. He sued Madison Square Garden. They had refused him entry because of his race. This was against New York's equal rights law.

Legal Career

Alexander graduated from Harvard Law in 1923. That same year, he married Sadie Tanner Mossell. She was his former classmate from Penn. Sadie later became the first Black woman to earn a law degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1927. They had two daughters, Rae and Mary. Raymond passed the Pennsylvania bar exam in 1923. This made him one of the few Black lawyers in the state.

Even with his great education, Alexander found it hard to get a job in Philadelphia. He eventually worked for a white lawyer named John R. K. Scott. Soon after, Alexander opened his own law office. He focused on representing Black people.

He quickly became well-known in Philadelphia's Black community. In 1924, he represented Louise Thomas. She was a Black woman accused of a serious crime. After she was found guilty, Alexander got her a new trial. In the new trial, Thomas was found not guilty. This was a very important moment in Pennsylvania's legal history. That same year, he sued a movie theater owner. The owner had refused to let Black ticket-holders in. Alexander lost the case, but it showed he was willing to fight for equal rights. Around this time, Alexander joined the "New Negro" movement. This group believed in self-help and fighting injustice. He also joined the National Bar Association (NBA). This group was for Black lawyers who were not allowed in other legal associations. Through the NBA, Alexander used both legal action and protests for equal rights. His law firm, which included his wife, moved to a new building.

Berwyn School Desegregation Case

In 1932, Alexander helped with efforts to desegregate schools in Berwyn, Pennsylvania. This was a town near Philadelphia. The local school district built a new elementary school. They then turned the old school into one only for Black students. This meant that schools that used to be mixed became segregated. Because of this, 212 African American students started to boycott, or refuse to attend, the public schools. Their families hired Alexander to take the issue to court.

With help from the NAACP, Alexander tried to negotiate with the school board. But the boycott continued into 1933. The state's Attorney General ordered the Black parents to be charged for not sending their children to school. Some parents refused to pay bail and stayed in prison as a protest. Alexander supported this strategy. The NAACP, however, thought it was too aggressive.

As the boycott continued into 1934, protest marches were held in Philadelphia. The Attorney General, who was running for governor, promised to find a solution. Alexander and others believed this was because Black voters were becoming more influential. By June, the school board agreed to let students attend both schools without regard to race. The parents then ended their boycott. The next year, Pennsylvania passed a stronger equal rights law. This law covered all public places, including schools. It also allowed private lawyers to sue businesses that segregated.

Fighting for Justice

After the Berwyn case, Alexander became very well-known in the Black legal community. He spoke at events across the country. He served as president of the National Bar Association from 1933 to 1935. He continued to take on important cases. For example, in 1942, he represented Thomas Mattox. Mattox was a Black teenager accused of a crime in Georgia. Alexander argued that Mattox would not get a fair trial in the South. The judge agreed and stopped the transfer.

The Trenton Six Case

In 1948, Alexander became involved in the case of the Trenton Six. This was a group of Black men accused of a serious crime in Trenton, New Jersey. Police got confessions from five of the six men. All were found guilty by an all-white jury and sentenced to death. The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) represented three of the men during their appeal. The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund asked Alexander to represent two others. In 1949, the Supreme Court of New Jersey ordered a new trial for the men.

In the 1951 re-trial, Alexander showed that the police had created false evidence. They wanted a quick conviction to calm public concerns. The judge also ruled out the confessions, as they were forced. After a long trial, four men were found not guilty. Two were found guilty, but the jury recommended life imprisonment instead of death. This was not a complete victory, but Alexander showed his great skill as a lawyer. He saved the lives of his clients. He also managed to keep his distance from communist groups, which was important during the Cold War.

Political and Judicial Career

Seeking a Judgeship

By the 1930s, Alexander's civil rights work led him into local politics. At that time, the Republican Party was very powerful in Philadelphia. Alexander ran for a judge position as a Republican in 1933. But he dropped out due to health reasons. He became frustrated with the Republican party. They only offered low-level jobs to Black people. Still, he thought Republicans were the best chance for Black advancement. He tried to convince party leaders to nominate a Black lawyer for a judge seat in 1937. He hoped it would be him. But he lost the primary election. This meant both parties had only white candidates for judge in 1937.

After this, Alexander joined many Black Americans in switching to the Democratic Party. However, by 1940, Alexander felt the Democrats were no better at electing Black judges. He also disliked the New Deal and the party's slow action on civil rights. So, he returned to the Republican Party. His wife, Sadie Alexander, stayed a Democrat. In 1946, President Harry S. Truman appointed her to his President's Committee on Civil Rights. Raymond Alexander rejoined the Democratic Party in 1947. He campaigned for Truman the next year.

After Truman's election, Alexander tried to get appointed to a federal court. He was also considered for a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. But the position went to William H. Hastie instead. Hastie became the first Black federal appeals court judge in 1950. Some believe Alexander's frequent party-switching hurt his chances. After failing to get a federal judge seat, Alexander tried for a foreign service job. He wanted to be the U.S. Ambassador to Haiti or Ethiopia, but he was not successful.

City Council Member

In the late 1940s, Alexander joined a growing reform movement in the Philadelphia Democratic Party. This group wanted to improve city government. In 1951, a new city charter was passed. Alexander won the Democratic primary to represent the 5th district on the City Council. In the election that November, Alexander won easily. He received 58% of the vote. Democrats won most council districts and elected a new mayor. This ended 67 years of Republican rule in the city.

Alexander's campaign promised to hire city workers based on skill, not political connections. He also wanted to increase the number of Black employees. This promise gained the trust of Black voters. In 1953, Alexander proposed that Girard College, an all-white school, admit Black students. If they refused, he wanted them to lose their tax-free status. The case went through the courts. The school finally desegregated in 1968, long after Alexander left City Council.

He was re-elected in 1955 with even more votes. He received 70% of the vote. On the city council, Alexander continued to push for civil service reform. In 1954, he successfully stopped other Democrats from weakening the new charter's reforms.

Judge

In 1958, a U.S. Representative resigned his seat to become a judge. The Democratic Party wanted a Black candidate to replace him. Alexander also announced his candidacy for the seat. His biographer suggests Alexander wanted to use this challenge to get the party to support him for a judgeship. His plan worked. Alexander soon dropped out of the race. The Governor then appointed Alexander to be a judge on the Court of Common Pleas No. 4. This made him the first Black judge on that court. On January 5, 1959, Alexander was sworn in. In the election later that year, he won a full ten-year term as a judge.

In his first year as a judge, Alexander noticed many Black defendants in court. He tried to help by creating a "Spiritual Rehabilitation Program." This program offered an alternate probation system for first-time offenders. Local churches and synagogues provided funding and help. The program received national attention for its new approach.

Alexander remained active as a civil rights leader. But he sometimes disagreed with younger activists about the best ways to achieve goals. For example, in 1962, he wanted more Black representation on a city council. But he disagreed with a call for a boycott of companies. In 1964, he supported Martin Luther King Jr.'s civil disobedience campaigns in the South. However, he felt some protests in the North hurt the cause. He asked Black leaders to "stop the needless demonstrations." In 1966, he criticized the Black Power movement. He called it "dangerous and divisive."

Despite these differences, Alexander continued to work for racial equality. In 1969, he called for the city to hire more Black employees. In 1972, he wrote an article asking the Philadelphia Police Department to do the same. He spoke out against black separatism, calling it "reverse racism." He focused more on how economic problems made racial issues worse. He called for a universal basic income and affirmative action to fix these problems. However, by the 1970s, some young Black people felt Alexander and his generation were "out of touch."

Death and Legacy

Raymond Pace Alexander reached the mandatory retirement age of 70. He retired from the court at the end of 1969. But he continued to serve as a senior judge. On November 25, 1974, Alexander was found dead in his judicial office. He had a heart attack. His funeral was held at Philadelphia's First Baptist Church. He was buried in West Laurel Hill Cemetery. In 2007, the University of Pennsylvania created a special professorship. It is named the Raymond Pace and Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander Professorship. It focuses on studying civil rights and race relations. Their daughters donated portraits of their parents to the law school.

Images for kids

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |