Silent Parade facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Silent Parade |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the reaction to the East St. Louis riots, and Anti-lynching movement |

|

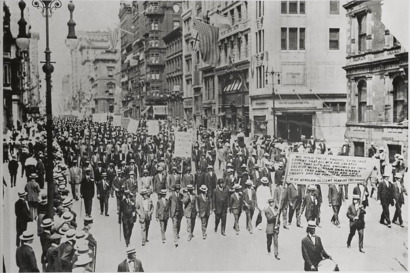

The 1917 Silent Parade in New York

|

|

| Date | July 28, 1917 |

| Location |

40°45′47″N 73°58′26″W / 40.762960°N 73.973946°W |

| Caused by | Black people deaths during the East St. Louis riots |

| Goals | To protest murders, lynchings, and other anti-Black violence; to promote anti-lynching legislation, and promote Black causes |

| Methods | Parade / public demonstration |

| Resulted in | Woodrow Wilson did not implement anti-lynching legislation |

The Silent Parade was a quiet march of about 10,000 African Americans in New York City on July 28, 1917. It started on Fifth Avenue at 57th Street. The NAACP and other community leaders organized this event. They wanted to protest violence against African Americans. This included recent lynchings (when a mob kills someone, often by hanging, without a legal trial) and the terrible East St. Louis riots.

Contents

Why the Silent Parade Happened

The East St. Louis Riots

Before 1917, many Black people moved from the Southern United States. They were looking for safer lives and more freedom. This movement was called the Great Migration.

In East St. Louis, Illinois, there were growing tensions between white and Black workers. Many Black people found jobs in local factories. In spring 1917, most white workers at the Aluminum Ore Company went on strike. The company then hired hundreds of Black workers to replace them.

Rumors started spreading about Black men and white women spending time together. This made the situation explode. Thousands of white men attacked African Americans in East St. Louis. They destroyed buildings and hurt people. The violence calmed down but then started again weeks later. This happened after a police officer was shot by Black residents. Thousands of white people marched and rioted in the city once more.

White mobs attacked Black people with great cruelty. The authorities did not protect innocent lives. This led to strong reactions from African Americans across the country. Marcus Garvey, a Black leader, called the riot a "wholesale massacre of our people." He said it was time to speak out against such "savagery." Many Black people felt they might never get full citizenship or equal rights in the United States.

Writers and civil rights activists, W. E. B. Du Bois and Martha Gruening, visited East St. Louis. They went there after the riot on July 2 to talk to witnesses. They wrote a detailed essay about the riots for The Crisis, a magazine published by the NAACP.

The Protest in New York City

On July 28, 1917, New York City was very hot. Between 8,000 and 15,000 African Americans marched silently. They protested the lynchings in places like Waco and Memphis. They especially protested the violence of the East St. Louis riots.

The march began at 57th Street and went down Fifth Avenue. It ended at 23rd Street. Protesters carried signs to show their anger. Some signs directly asked President Woodrow Wilson for help. A police escort on horses led the parade. Women and children marched next, all dressed in white. The men followed, dressed in black. People of all races watched from the sidewalks of Fifth Avenue.

Black Boy Scouts handed out flyers. These flyers explained why they were marching. White people stopped to listen to Black marchers explain their reasons. Some white onlookers also showed support and sympathy.

Some messages on the flyers said:

- We march because we believe prejudice and unfairness must end.

- We march because it is wrong to be silent when such cruel acts happen.

- We march because we want our children to have a better and fairer life than we have had.

This parade was the first large protest in New York made up only of Black people. The New York Times wrote about it the next day. They said 8,000 Black people marched "without a shout or a cheer." They used banners to show their cause. These banners mentioned "Jim Crow" (laws that enforced racial segregation), unfair voting rules, and the riots in Waco, Memphis, and East St. Louis.

News coverage of the march helped change how Black people were seen in the United States. The parade and its news stories showed the NAACP as an organized and polite group. This helped more white and Black people learn about the NAACP.

The marchers hoped to convince President Wilson to keep his promises. He had promised African American voters that he would support anti-lynching laws. He also promised to help Black causes. Four days after the parade, Black leaders, including Madam C. J. Walker, went to Washington D.C. They had an appointment with the president. But they were told Wilson had "another appointment." They left a petition for him. It reminded him that African Americans were serving in World War I. It also urged him to stop future riots and lynchings. However, Wilson did not keep his promises. In fact, unfair treatment of African Americans by the government increased under his leadership.

Organizers of the Parade

The Harlem branch of the NAACP led the parade. Many important church and business leaders also helped plan the event. The Crisis magazine, published by the NAACP, quoted the New York World about the leaders. The Rev. Dr. H. C. Bishop was the parade's President. The Rev. Dr. Charles D. Martin was the Secretary. The Rev. F. A. Cullen was Vice President. Other leaders included J. Rosamond Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, and W. E. B. Du Bois.

The Legacy of the Silent Parade

The Silent Parade was the first protest of its kind in New York. It was also the second time African Americans publicly protested for civil rights. The parade helped people feel empathy. For example, Jewish people remembered similar attacks against them called pogroms. The media also started to support African Americans in their fight against lynching and unfair treatment.

Another large silent parade happened in Newark in 1918. Before that parade, NAACP members spoke in churches about the march. They also talked about the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill. Women from the New Jersey Federation of Colored Women's Clubs marched with men. They carried signs. After the parade, a big meeting was held at the Newark Armory.

Another NAACP-sponsored silent march took place on August 26, 1989. This march protested recent decisions by the Supreme Court of the United States. Over 35,000 people took part. Benjamin Hooks, the NAACP director, encouraged this march.

In East St. Louis, there was a week-long event to remember the riots and march. This happened just before the 100th anniversary on July 28, 2017. About 300 people marched from the SIUE East St. Louis Higher Learning Center to the Eads Bridge. Everyone marched in silence. Many women wore white, and men wore black suits. Those who could not walk followed in cars.

On the 100th anniversary, Google honored the parade with a Google Doodle. Many people in 2017 said they first learned about the Silent Parade from that day's Google Doodle.

A group of artists and the NAACP planned to re-enact the silent march in New York on July 28, 2017. About 100 people participated, many wearing white. They could not march down Fifth Avenue because of Trump Tower. So, the event took place on Sixth Avenue instead. The group held up pictures of people who had recently been victims of violence by police and others in the United States.

Images for kids

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |