Eads Bridge facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Eads Bridge |

|

|---|---|

The bridge in 2025

|

|

| Coordinates | 38°37′41″N 90°10′17″W / 38.62806°N 90.17139°W |

| Carries | 4 highway lanes 2 MetroLink tracks |

| Crosses | Mississippi River |

| Locale | St. Louis, Missouri and East St. Louis, Illinois |

| Maintained by | City of St. Louis |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Arch bridge |

| Total length | 6,442 ft (1,964 m) |

| Width | 46 ft (14 m) |

| Longest span | 520 ft (158 m) |

| Clearance below | 88 ft (27 m) |

| History | |

| Designer | James B. Eads |

| Construction begin | 1867 |

| Opened | 1874 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 7,100 (2014) |

|

Eads Bridge

|

|

| NRHP reference No. | 66000946 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | January 29, 1964 |

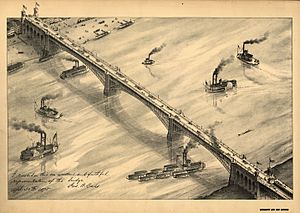

The Eads Bridge is a super cool bridge that connects St. Louis, Missouri, and East St. Louis, Illinois, over the mighty Mississippi River. It's named after its amazing designer, James Buchanan Eads. Construction started way back in 1867 and finished in 1874. This bridge was the very first one to cross the Mississippi River south of the Missouri River. It's also the oldest bridge still standing on the entire river!

This bridge was a huge deal for engineering. It was one of the first big projects to use steel for its main structure. Before this, most large buildings used iron. The bridge's foundations go more than 100 feet (30 meters) deep underwater. These were the deepest underwater structures ever built at the time! They used a special method called pneumatic caissons to build them. The middle arch of the bridge was 520 feet (158 meters) long, which was the longest rigid span ever built then. These new ideas helped engineers build other famous bridges, like the Brooklyn Bridge.

Today, the Eads Bridge is a famous landmark in St. Louis, almost as well-known as the Gateway Arch. You can drive cars and walk across its upper deck. The lower deck now carries the St. Louis MetroLink light rail system, connecting people between Missouri and Illinois. The bridge is so important that it's listed as a National Historic Landmark.

Contents

The Amazing Eads Bridge

Building a River Giant

The Eads Bridge was built by the Illinois and St. Louis Bridge Company. A company called Keystone Bridge Company, started by Andrew Carnegie, helped put together the steel parts.

Back then, railroads were becoming very popular, and river shipping was slowing down. St. Louis wanted to stay an important city for trade. The bridge was planned to connect railroads and roads across the river, helping St. Louis grow. Even though James Eads had never built a bridge before, he was chosen as the main engineer.

Overcoming Big Challenges

Building this bridge was incredibly difficult! The Mississippi River has a very strong current and lots of ice in winter. Also, steamboat companies didn't want a bridge to block their boats. They made rules that the bridge had to be super tall and have very long sections between its supports. They thought these rules would make it impossible to build, so no bridge would ever get made.

But James Eads found a way! He used a special design with three strong arches. These arches were supported by two piers (big columns) in the middle of the river and two supports on the riverbanks. The bridge had two levels: an upper deck for cars and a lower deck for trains.

The ground under the river was also a problem. The bedrock was very deep, about 125 feet (38 meters) on the Illinois side and 85 feet (26 meters) on the Missouri side. Eads's team had to dig down to this bedrock to make sure the bridge was stable.

New Ways to Build

This bridge was special because it was the first major building to use chromium steel for its structure. Eads believed steel was perfect for the arch design because it was very strong.

To build the deep foundations, engineers used huge caissons. These were like giant, upside-down boxes filled with compressed air. Workers went inside these caissons underwater to dig out sand and mud. This allowed the piers to sink deep into the riverbed. Working in these deep caissons was dangerous. Many workers got sick from something called "caisson disease" (also known as "the bends"). Sadly, 15 workers died, and many others were hurt.

Because they couldn't put up temporary supports in the river (they would block boats), Eads's engineers invented a clever system to build the arches. They used a "cantilever" method, where parts of the arch were built outwards from the piers, hanging in the air until they met in the middle.

A Grand Opening

The Eads Bridge was a huge success! James Eads received 47 patents for his bridge ideas and building tools. On July 4, 1874, President Ulysses S. Grant officially opened the bridge. To prove it was safe, a circus elephant named John Robinson walked across it. People believed elephants could sense if a structure was unsafe. Two weeks later, 14 locomotives crossed the bridge at the same time to show how strong it was. The opening day was a massive celebration with a parade that stretched for 15 miles (24 kilometers) through St. Louis!

At the time, The New York Times newspaper even called it "The World's Eighth Wonder." Building the bridge cost almost $10 million, which would be a huge amount of money today.

Early Years of the Bridge

Even though the Eads Bridge was an engineering marvel, it had some money problems at first. St. Louis didn't have good train stations to connect with the bridge, so railroads didn't use it much. This meant the bridge didn't collect enough money from tolls. Within a year, the company that owned the bridge went bankrupt.

Later, the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis (TRRA) took over the bridge. In 1898, the bridge was even featured on a $2 postage stamp!

In 1949, engineers tested the bridge's strength and found it was even stronger than Eads had first thought. It could hold much heavier loads. Many experts still consider the Eads Bridge one of the greatest bridges ever built. In 1964, it was named a National Historic Landmark because of its amazing design and construction.

The Bridge Today

For a long time, only passenger trains used the Eads Bridge's lower deck. But as more people started driving cars, train travel became less popular. By the 1970s, the train tracks on the Eads Bridge were not used anymore.

In 1989, the bridge was given to the Bi-State Regional Transportation Authority and the City of St. Louis. They wanted to use it for the new MetroLink light rail system. MetroLink trains started running over the bridge in 1993.

The upper deck for cars was closed for a while, from 1991 to 2003, for repairs. Now, it's open again for cars and people walking or biking.

From 2012 to 2016, the Eads Bridge went through a big repair project. Workers replaced old steel parts, cleaned and repainted the entire structure, fixed damaged areas, and upgraded the MetroLink tracks. This project cost $48 million and helped make sure the bridge will last until at least 2091!

The Connecting Tunnel

Building the Tunnel

City leaders wanted the bridge to connect directly to the heart of downtown St. Louis. But there wasn't enough space for train tracks in the busy downtown area. So, they decided to build a tunnel to connect the bridge to the main railroad lines.

James Eads also designed this tunnel. It was a "cut and cover" tunnel, meaning they dug a trench, built the tunnel, and then covered it up. It was about 4,000 feet (1,200 meters) long and 30 feet (9 meters) below street level. Building the tunnel had its own problems, like quicksand and underground springs.

On the bridge's opening day, July 4, 1874, a special 15-car train with 500 important people crossed the Eads Bridge and traveled through the new tunnel.

How the Tunnel Worked

One challenge with trains in tunnels is smoke. Special coke-burning engines were designed to produce less smoke. News reports from the early days mentioned passengers coughing because the tunnel's ventilation wasn't fully ready.

The Eads Bridge and its tunnel are now used by Metrolink, the light rail system for St. Louis.

See also

In Spanish: Puente Eads para niños

In Spanish: Puente Eads para niños

- List of bridges documented by the Historic American Engineering Record in Illinois and in Missouri

- List of crossings of the Upper Mississippi River

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Illinois and in Missouri

- National Register of Historic Places listings in St. Clair County, Illinois and in Downtown and Downtown West St. Louis

- List of bridges on the National Register of Historic Places in Illinois and in Missouri