Cecil Sharp facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Cecil Sharp

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 22 November 1859 Camberwell, Surrey, England

|

| Died | 23 June 1924 (aged 64) |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Clare College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Folklorist and song collector |

|

Notable work

|

English Folk Song: Some Conclusions

English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians The Country Dance Book |

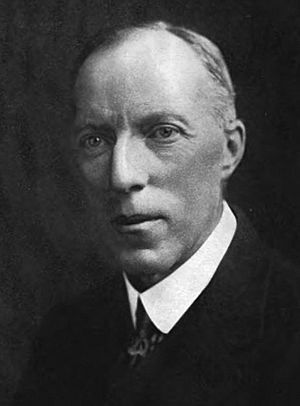

Cecil James Sharp (born November 22, 1859 – died June 23, 1924) was an English expert who collected old folk songs, dances, and music. He was also a teacher, composer, and musician. He played a very important part in bringing back interest in English folk music and dance during the early 1900s. Many people consider him the most important person in studying English folk songs and music.

Sharp collected over 4,000 folk songs. He found them in South-West England and in the Appalachian Mountains of the United States. He published many songbooks based on his findings, often with piano music. He also wrote an important book called English Folk Song: Some Conclusions. He wrote down how English Morris dancing was done. He helped bring back both Morris dancing and English country dance. In 1911, he helped start the English Folk Dance Society. This group later joined with the Folk-Song Society to form the English Folk Dance and Song Society.

Cecil Sharp's work still influences English orchestral music and how children learn to sing in school. Many popular folk musicians from the 1960s until today have used songs that Sharp collected. Many Morris dance teams in England and other countries still perform dances he helped save. In the USA, the Country Dance and Song Society was started with Sharp's help. Dancers there still enjoy the styles he helped develop.

Over the past 40 years, people have discussed Sharp's work a lot. There have been talks about whether he chose songs carefully, if he focused too much on nationalism, or if he changed songs too much.

Contents

Early Life

Cecil Sharp was born in Camberwell, Surrey, England. He was the oldest son of James Sharp and Jane Bloyd. His father was a slate merchant who loved old things like archaeology, architecture, furniture, and music. His mother also loved music. They named him after Saint Cecilia, who is the patron saint of music, because he was born on her special day.

Sharp went to Uppingham School. He left at age 15 and studied privately for University of Cambridge. He was part of the rowing team at Clare College, Cambridge. He earned his degree in 1882.

In Australia

Sharp decided to move to Australia after his father suggested it. He arrived in Adelaide in November 1882. In early 1883, he got a job as a clerk at a bank. He also studied law. In 1884, he became an assistant to the Chief Justice, Sir Samuel James Way. He worked there until 1889, when he quit to focus entirely on music.

Soon after arriving, he became an assistant organist at St Peter's Cathedral. He also led the Government House Choral Society and the Cathedral Choral Society. Later, he led the Adelaide Philharmonic. In 1889, he became a joint director of the Adelaide College of Music with I. G. Reimann.

He was a very good lecturer. Around 1891, his partnership with Reimann ended. Reimann continued the school, which later became the Elder Conservatorium of Music. Many friends asked Sharp to stay in Adelaide, but he decided to return to England. He arrived back in January 1892. While in Adelaide, he wrote music for an operetta called Dimple's Lovers. He also wrote two light operas, Sylvia and The Jonquil. He also wrote music for some nursery rhymes.

Return to England

In 1892, Sharp returned to England. On August 22, 1893, he married Constance Dorothea Birch in Somerset. She also loved music. They had three daughters and one son. In 1893, he started working as a music teacher at Ludgrove School in North London. He stayed there for 17 years and took on other music jobs too.

From 1896, Sharp was the Principal of the Hampstead Conservatoire of Music. This was a part-time job that came with a house. In July 1905, he left this job after a disagreement about pay. After that, his money mainly came from giving lectures and publishing books about folk music.

English Folk Song and Dance

Sharp was not the first person to study folk songs in England. Others like Lucy Broadwood and Sabine Baring-Gould had already collected them. Sharp became interested in English folk music in 1899. He saw the Headington Quarry Morris dancers perform near Oxford. He met their musician, William Kimber, who was great at playing the anglo-concertina and dancing. Sharp asked to write down some of the dances. Kimber became Sharp's main source for Morris dancing notes and a lifelong friend.

In August 1903, Sharp visited his friend Charles Marson in Hambridge, Somerset. Marson was a vicar and a Christian Socialist whom Sharp had met in Adelaide. There, Sharp heard the gardener, John England, sing the traditional song The Seeds of Love. Sharp had joined the Folk-Song Society in 1901, but this was his first time hearing a folk song "in the field." This experience changed his career path.

Between 1904 and 1914, he collected over 1,600 songs in rural Somerset. He also collected over 700 songs from other parts of England. He published five books of Folk Songs from Somerset and many other books, including sea shanties and folk carols. He became a strong supporter of folk songs. He gave many lectures and wrote down his ideas in English Folk Song: Some Conclusions in 1907.

Between 1907 and World War I, Sharp focused more on traditional dance. In 1905, he met Mary Neal. She ran the Espérance Girls' Club, which helped young working-class women in London. She wanted suitable dances for them to perform. They started working together, but later had different ideas. Sharp wanted dances to be exactly traditional, while Neal liked them to be more lively and showy. This led to disagreements about how Morris dancing should be taught. Sharp continued his dance interest by teaching at the School of Morris Dancing. He also collected more dances, publishing five books of The Morris Book (1907–1913). Some people say Sharp focused too much on the Cotswold style of Morris dancing, even though he did collect other styles.

Sharp also became interested in sword dancing. Between 1911 and 1913, he published three books called The Sword Dances of Northern England. These books described the rare Rapper sword dances of Northumbria and Long Sword dances of North Yorkshire. His work helped bring these traditions back to life in their home areas and elsewhere.

Sharp as Fieldworker

Sharp, sometimes helped by Marson, would ask around in small Somerset communities for people who knew old songs. He found many singers, including sisters Louisa Hooper and Lucy White from Langport, who sang many songs. Sharp was good at connecting with people from different backgrounds and became friends with several singers. After he died, Louisa Hooper wrote about how generous he was with payments, gifts, and outings. He also collected many songs from Gypsy communities.

In the Appalachian Mountains, Sharp and Maud Karpeles used local knowledge to find singers. They also made lasting friendships there.

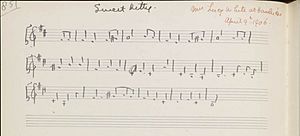

Sharp usually wrote down songs by listening carefully. He tried using a phonograph (an early record player), but he found it too big to carry and thought it might make singers nervous. He got help writing down the words from Marson in Somerset and Karpeles in the Appalachians. Sharp wrote down the music himself. His notes, which included small changes in the melodies, were usually very accurate. Sharp was careful to write down the singers' names, locations, and dates. This helped later researchers learn more about them. He also took many photos of singers at their homes, which gives us a valuable look at life for working people in both South-West England and the Appalachian Mountains.

Folk Song in Schools

In 1902, when public schooling was just starting, Sharp, who was a music teacher, created a songbook for schools. It had a mix of patriotic "National Songs" and folk songs. As he learned more about folk songs, he decided against the "National Songs." They were not in his 1906 collection, English Folk Songs for Schools, which he wrote with Baring-Gould.

Sharp strongly believed that folk songs should be a main part of school lessons. In 1905, he argued with the Board of Education because their list of recommended songs for schools included many "National Songs." His friends Frank Kidson and Lucy Broadwood did not agree with him. The Folk-Song Society committee voted to approve the Board's list, which caused a disagreement with Sharp.

Sharp’s Theories

After his disagreement with the Board of Education, Sharp published English Folk Song: Some Conclusions. In this book, he shared his ideas about how folk songs developed. He believed they grew over time through oral transmission, meaning they were passed down by word of mouth from one generation to the next.

Sharp had three main ideas:

- Continuity: Individual songs had survived for centuries, still recognizable.

- Variation: Songs existed in many different versions because singers changed them.

- Selection: A community would choose the most pleasing version of a song.

He thought this meant songs didn't have one single composer. Instead, they evolved "as the pebble on the sea shore is rounded and polished by the action of the waves." However, some people in the folk song movement, like Kidson, were not sure about this idea.

Sharp also believed that folk songs showed what it meant to be English. He thought it was very important to teach them in schools to help children feel a sense of national identity. He also suggested that folk melodies should be the basis for new English classical music. This idea was shared by other composers like Ralph Vaughan Williams.

Bowdlerisation

Some of the original folk song lyrics were not suitable for publication in the early 1900s, especially in school books. However, Sharp carefully wrote down these lyrics in his notebooks. This way, the original versions were saved for the future. Sharp's main goal was to share the unique melodies of these songs through music education. This might explain why he focused more on the tunes than on every single word.

English Folk Dance and Song Society

In 1911, Sharp helped create the English Folk Dance Society. This group promoted traditional dances by holding workshops all over the country. In 1932, it joined with the Folk-Song Society to form the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS). The main building for the EFDSS in London is called Cecil Sharp House in his honor.

Influence on English Classical Music

Sharp's work happened at a time when there was a strong feeling of nationalism in classical music. The idea was to make English classical music unique by using the special melodies and sounds of its national folk music. One composer who did this was Ralph Vaughan Williams. He used many melodies from Sharp’s collections in his own music. He also used melodies he collected himself in England.

In America

During World War I, Sharp found it hard to make a living from his usual work in England. So, he decided to try working in the United States. In 1915, he was asked to be a dance consultant for a play in New York called A Midsummer Night’s Dream. He then gave successful lectures and classes across the country about English folk songs and dances.

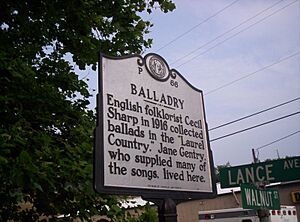

He met a rich helper named Helen Storrow in Boston. With her and others, he helped set up the Country Dance and Song Society. He also met Olive Dame Campbell. She had collected many British-origin ballads in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. Her collection was so good that Sharp decided to go on several song-collecting trips into the remote mountains with his helper Maud Karpeles. This was between 1916 and 1918. They followed in the footsteps of Olive Campbell and other collectors.

They traveled through the Appalachian mountains in Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee. They often walked many miles over rough land. Sharp and Karpeles found a huge number of folk songs. Many were of British origin, but they were different from the versions Sharp had found in England. Some songs had even disappeared in England. In remote log cabins, Sharp would write down the tunes by listening. Karpeles wrote down the words. They collected songs from singers like Jane Hicks Gentry, Mary Sands, and young members of the Ritchie family of Kentucky. Sharp was especially interested in the tunes, which he found very beautiful.

Sharp focused strongly on "Englishness" in his work. Some people have criticized him for not recognizing that many songs he collected came from the Scottish rather than the English folk tradition.

Olive Dame Campbell and her husband John led Sharp and Karpeles to areas with many white people of English or Scots-Irish background. So, the collectors did not fully see the mix of cultures in Appalachia, which included White, Black, Indigenous, and multiracial Americans. They also missed how these groups influenced each other's folk traditions. For example, Sharp saw a type of square dancing in white communities that he called the "Kentucky Running Set." He thought it was a survival of a 17th-century English style. But it actually had important African-American and European parts.

When looking for communities with British-origin songs, Sharp and Karpeles avoided German-American communities. Once, they turned back from a village when they realized it was an African-American settlement. Sharp used an old, offensive term in his notes, writing: "We tramped – mainly uphill. When we reached the cove we found it peopled by n----s ... All our troubles and spent energy for nought." However, unlike some other collectors at the time, he did write down ballads from two Black singers. He described one, "Aunt Maria [Tomes]," as "an old coloured woman who was a slave... she sang very beautifully in a wonderfully musical way and with clear and perfect intonation... rather a nice old lady."

Sharp and Karpeles wrote down a huge number of songs. Many of these songs might have been lost otherwise. Their work helped keep the tradition of ballad singing alive in the Appalachian Mountains. One expert called their collection "without question the foremost contribution to the study of British-American folk-song." Another called it a "monumental contribution." However, some argue that their focus on old British songs made them miss the full cultural diversity of Appalachian folk music.

A recent book by Elizabeth DiSavino (2020) suggested that Sharp did not give enough credit to female singers or Scottish sources. However, Sharp did mention both in the introduction to his book English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians.

Political Views

Sharp supported the political left of his time. He joined the Fabian Society, a Socialist group, in 1900. Later in life, he supported the Labour Party. When he was younger, he was seen as a radical. A colleague said he liked to "pull the legs off the Tories" (meaning he liked to tease conservative people).

While at Cambridge, Sharp listened to lectures by William Morris. This likely influenced his later description of himself as a "conservative socialist." This meant he was against capitalism but also wary of the Industrial Revolution and modern life. He believed rural life was better than city life. He wrote about his anger at the "injustice of class distinctions." He believed in working together as a group rather than private businesses. Later in life, he wrote that he felt sympathy for striking coal miners. He also believed in democracy over strict governments, saying that "any form of collectivist government must also be democratic if it is to function properly." He was not sure about the Bolshevik revolution in Russia.

Sharp was against the death penalty and was a vegetarian his whole life. However, he did not support the Suffragette movement, which fought for women's right to vote. His colleague and biographer Maud Karpeles thought this was because he disliked their methods, not because he disagreed with women voting. Despite this, he stayed friends with his sister Evelyn, who was a strong suffragist and was even put in prison for her activities. After she was released, she wrote to Sharp saying she didn't want to argue about it and didn't think he was a "confirmed 'anti'." Sharp was a nationalist and believed that hearing English folk songs would create a feeling of patriotism.

Criticism

Sharp's ideas were very popular for 50 years after he died. This was partly because of a biography written by his student Maud Karpeles, which praised him without much criticism. She also used his ideas to define folk song for the International Folk Music Council in 1954. A. L. Lloyd, an important thinker of the second folk song revival in the 1960s, said he disagreed with Sharp's ideas. But in reality, he followed much of Sharp's thinking. Lloyd disagreed with Sharp's idea that folk songs could only be found in isolated rural areas. He also called Sharp's piano arrangements "false." But he praised Sharp's skill as a collector and admired his analysis of certain tunes. He used many examples from Sharp's notes.

In the 1970s, David Harker offered a different view. He questioned why folk revivalists did what they did. He accused Sharp of changing his research for his own ideas. Harker wrote more about this in his important 1985 book Fakesong. He said that the idea of folk song was "intellectual rubble" that needed to be cleared away. He criticized many scholars. He saw folk song collecting as a way for richer people to take advantage of working-class people. Sharp, in particular, was strongly criticized. Harker, who was an expert on printed songs, argued against the idea of oral tradition. He said that most of what Sharp called "folk song" actually came from printed copies sold to people. He also claimed that Sharp and Marson had changed the songs, making "hundreds of alterations, additions and omissions" in their published work.

Fakesong led to many people looking at Sharp's work differently. Michael Pickering said Harker had given a "firm foundation for future work." Vic Gammon noted that Fakesong became very influential among some left-wing groups in Britain. He called it the "beginning of critical work" on the early folk music movement, but also said that "this does not mean that Harker got it all right."

C. J. Bearman offered a more detailed criticism. He pointed out many mistakes in Harker's claims that Sharp and Marson's choices of songs for publication were unfair. Bearman also disagreed with Harker's claims of widespread changes to songs. He said Harker's facts were wrong or exaggerated. He also pointed out that Harker ignored the rules about what could be published in the early 1900s. And he noted that Sharp had been open about his changes and had saved the original texts. In another paper, Bearman disagreed with Harker's statistics about Somerset communities.

However, Harker's idea that much of the material collected by Sharp and others came from commercial print is now widely accepted. Also, Sharp's narrow definition of what counted as "folk song" has been broadened a lot in more recent studies.

In 1993, Georgina Boyes wrote The Imagined Village. This book criticized the folk song revival of the Victorian and Edwardian eras. It said they created a false idea of a rural community – "The Folk" – and collected songs that didn't truly represent them. The book also criticized Sharp for being too controlling, which some of his friends complained about. It saw his disagreement with Mary Neal over Morris dancing as a man refusing to share power with a woman. However, other accounts by Roy Judge share the blame more evenly and focus on their different ideas. Sharp has also been criticized for his attitude towards dance activist Elizabeth Burchenal in the USA.

Sharp's song collecting in the USA has also been discussed by American scholars. Henry Shapiro said Sharp was partly responsible for the idea that Appalachian mountain culture was purely "Anglo-Saxon." Benjamin Filene and Daniel Walkowitz claimed that Sharp did not collect fiddle tunes, hymns, newer songs, or songs of African-American origin. David Whisnant made similar claims about his selectivity. But he also praised Sharp for being "serious, industrious and uniformly gracious to and respectful of local people." More recently, Phil Jamison stated that Sharp "was interested only in English music and dances. He ignored the rest." However, Brian Peters' detailed study of Sharp's collection found many American-made songs, plus hymns, fiddle tunes, and songs that Sharp himself described as having "negro" origins.

Selected Works

- Cecil Sharp's Collection of English Folk Songs, Oxford University Press, 1974; ISBN: 0-19-313125-0.

- English folk songs from the southern Appalachians, collected by Cecil J. Sharp; comprising two hundred and seventy-four songs and ballads with nine hundred and sixty-eight tunes, including thirty-nine tunes contributed by Olive Dame Campbell, edited by Maud Karpeles. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1932.

- English folk songs, collected and arranged with pianoforte accompaniment by Cecil J. Sharp, London: Novello (1916). This volume has been reprinted by Dover Publications under ISBN: 0-486-23192-5 and is in print.

- English Folk Song: Some Conclusions (originally published 1907. London: Simpkin; Novello). This work has been reprinted a number of times. For the most recent (Charles River Books), see ISBN: 0-85409-929-8.

- The Morris Book a History of Morris Dancing, With a Description of Eleven Dances as Performed by the Morris-Men of England by Cecil J. Sharp and Herbert C MacIlwaine, London: Novello (1907). Reprinted 2010, General Books; ISBN: 1-153-71417-5.

See also

- Country Dance and Song Society, an American folk arts organisation spun off from chapters of Sharp's English Folk Dance Society

- William Kimber

- Lucy White

- Jane Hicks Gentry

- Mary Neal

- Elizabeth Burchenal

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |