Eileen Gray facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Eileen Gray

|

|

|---|---|

Eileen Gray

|

|

| Born |

Kathleen Eileen Moray Smith

9 August 1878 Enniscorthy, County Wexford, Ireland

|

| Died | 31 October 1976 (aged 98) Paris, France

|

| Alma mater | Slade School of Fine Art Académie Julian Académie Colarossi |

| Occupation | Architect, furniture designer |

| Parent(s) | James McLaren Smith Eveleen Pounden |

| Buildings | E-1027 Tempe a Païa House |

| Design | "Dragons" armchair Bibendum Chair E-1027 table |

Eileen Gray (born Kathleen Eileen Moray Smith; 9 August 1878 – 31 October 1976) was an amazing Irish architect and furniture designer. She became a leader in the Modern Movement in architecture. This movement focused on simple, useful designs. Throughout her career, she worked with many famous European artists. Her most well-known work is a house called E-1027 in France.

Contents

- Early Life: Where Did Eileen Gray Grow Up?

- Education: How Did Eileen Gray Learn Her Skills?

- Interior Design: What Kind of Furniture Did Eileen Gray Make?

- Architecture: What Buildings Did Eileen Gray Design?

- World Wars: How Did Wars Affect Eileen Gray's Work?

- Later Life: What Happened to Eileen Gray in Her Old Age?

- Personal Life: What Was Eileen Gray Like?

- Posthumous Recognition: How Is Eileen Gray Remembered Today?

- See also

Early Life: Where Did Eileen Gray Grow Up?

Eileen Gray was born Kathleen Eileen Moray Smith on August 9, 1878. Her family lived at Brownswood, a large estate near Enniscorthy in County Wexford, Ireland. She was the youngest of five children.

Her father, James McLaren Smith, was a Scottish landscape painter. He really encouraged Eileen's interest in art, like painting and drawing. Even though he wasn't super famous, he wrote to many important artists of his time.

When Eileen was eleven, her parents divorced. Her father then moved to Europe to live and paint there.

Eileen's mother, Eveleen Pounden, became the 19th Baroness Gray in 1895. This happened after her uncle passed away. Even though her parents were separated, Eileen's father changed his name to Smith-Gray. From then on, all four children were known as Gray.

Eileen spent her childhood between Brownswood House in Ireland and the family's home in Kensington, London. In 1898, she was presented as a debutante at Buckingham Palace. This was a formal event for young women of her social class.

Both Eileen's brother and father died in the year 1900.

Education: How Did Eileen Gray Learn Her Skills?

Eileen Gray briefly went to a school in Dresden, Germany. But mostly, she was taught by governesses at home.

Her serious art education began in 1900 at the Slade School in London. Eileen studied fine arts at Slade from 1900 to 1902. It was common for young women of her background to study fine arts. However, Slade was a bit unusual because it was known as a "bohemian" school. Its classes were often co-educational, which was not typical back then. Eileen was one of 168 female students in a class of 228.

Eileen had many influential teachers at Slade. These included Philip Wilson Steer, a Romantic landscape painter, and Henry Tonks, a surgeon and figure painter.

While at Slade, Eileen met furniture restorer Dean Charles in 1901. Charles introduced her to the art of lacquering. She started taking lessons in this technique from his company in Soho.

In 1902, Eileen moved to Paris with two friends, Kathleen Bruce and Jessie Gavin. They first enrolled at the Académie Colarossi, an art school popular with students from other countries. Soon after, they switched to the Académie Julian.

In 1905, Eileen returned to London to be with her sick mother. For the next two years, she continued studying lacquering with Dean Charles. After that, she went back to Paris. When she returned, Eileen bought an apartment in the rue Bonaparte. She then began training with Seizo Sugawara. Sugawara was from Jahoji, a village in northern Japan famous for its lacquer work. He was in Paris to fix lacquer pieces that Japan had sent to a big exhibition. Eileen was so dedicated to learning this craft that she got "lacquer disease." This was a painful rash on her hands, but it didn't stop her from working.

In 1910, Eileen Gray opened a lacquer workshop with Sugawara. By 1912, she was creating special pieces for some of Paris's wealthiest clients.

At the start of World War I, Eileen served as an ambulance driver. Later, she returned to England with Sugawara to wait out the war.

Interior Design: What Kind of Furniture Did Eileen Gray Make?

After World War I, Eileen Gray and Sugawara went back to Paris. In 1917, Eileen was hired to redesign the Rue de Lota apartment. This apartment belonged to Juliette Lévy, a well-known socialite and owner of a fashion house.

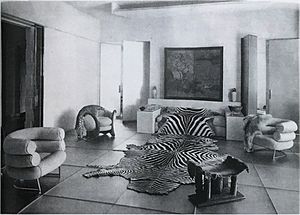

The Rue de Lota apartment has been called a perfect example of Art Deco style. A magazine from 1920 described it as "thoroughly modern." It also noted that it still had a "feeling for the antique." The furniture in the apartment included some of Eileen Gray's most famous designs. These were the Bibendum Chair and the Pirogue Day Bed.

The Bibendum chair was inspired by the Michelin Man. It had tire-like shapes on a shiny steel frame. The chair's soft, rounded shape reminded people of women in Renaissance paintings. Its geometric design also showed the influence of modern art movements. The Pirogue Day Bed was shaped like a gondola, a type of boat. It was finished with a special bronze lacquer. This design was inspired by Polynesian dugout canoes. This "boat-bed" might also have been influenced by the Irish currach, another type of boat.

The success of this project led Eileen Gray to open her own shop in 1922. It was called Jean Désert and was located on the fashionable Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris. The shop's name came from an imaginary male owner named "Jean" and Gray's love for the North African desert. Eileen Gray designed the shop's front herself. Jean Désert sold abstract, geometric rugs designed by Gray. These rugs were woven in Evelyn Wyld's workshops. Famous clients included James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and Elsa Schiaparelli.

At first, Eileen Gray used fancy materials like exotic woods, ivory, and furs. But in the mid-1920s, her designs became simpler and more industrial. This showed her growing interest in the work of architects like Le Corbusier. These Modernist designers valued usefulness and mathematical ideas over fancy decorations.

Jean Désert closed in 1930 because it was losing money.

Architecture: What Buildings Did Eileen Gray Design?

By 1921, Eileen Gray was working closely with Romanian architect and writer Jean Badovici. He was 15 years younger than her. Badovici encouraged her growing interest in architecture. From 1922 to 1926, Eileen taught herself about architecture. She never had formal training as an architect. She read books about theory and technical skills. She also took drafting lessons. She even arranged for Adrienne Gorska to take her along to building sites. Eileen also traveled with Badovici to study important buildings. She learned a lot by redesigning architectural plans.

In 1926, she began working on a new holiday home near Monaco. She planned to share it with Badovici. Because a foreigner in France couldn't fully own property, Gray bought the land. She put it in Badovici's name, making him her "client" on paper. Building the house took three years. Eileen Gray stayed on site during construction, while Badovici visited sometimes.

The house was given the mysterious name E-1027. This was a secret code for their names. The "E" stood for Eileen, "10" for J (Jean), "2" for B (Badovici), and "7" for G (Gray). E-1027 is often called a masterpiece of architecture.

E-1027 is a white, box-shaped building. It was built on rocky land and raised on pillars. Some say E-1027 followed Le Corbusier's "Five Points of the New Architecture." This meant it had an open floor plan, stood on pillars, had horizontal windows, an open front, and a roof you could reach by stairs. However, Gray thought that architects focused too much on the outside of buildings. She wrote that the inside plan should not just be a side effect of the outside. Instead, it should lead to a "complete harmonious, and logical life."

According to architecture critic Rowan Moore, E-1027 "grows from furniture into a building." By this time, Eileen Gray loved lightweight, useful, multi-purpose furniture. She called it "camping style." She designed a tea trolley with a cork surface to stop cups from rattling. She also placed mirrors so visitors could see the back of their heads. At the entrance of E-1027, Gray created a special space for hats. It had net shelves that allowed a clear view without dust settling.

When E-1027 was finished, Badovici dedicated an issue of his magazine to it. He even said he was a joint architect. However, Jennifer Goff, a curator at the National Museum of Ireland, proved this wasn't true. Her research showed that all the existing plans for the house were drawn only by Eileen Gray. Badovici's role was mainly as the client and a consulting architect. In her six-year partnership with Badovici, Gray designed 9 buildings and renovations. Four of these were credited to Badovici.

Eileen Gray and Badovici later went their separate ways. In 1931, Gray started working on a new house called Tempe à Pailla. It was located above the nearby town of Menton. The name Tempe à Pailla means "Time and Hay" in English. It refers to a local saying that both are needed for figs to ripen. It was a small two-bedroom house with a large terrace. Much of the furniture could change its use. For example, wardrobes could expand, and a dining bench could fold for storage or turn into a small table.

With Tempe à Pailla, Gray moved away from Le Corbusier's open plan idea. She created more separate spaces while still making the most of the house's amazing views. Gray's design also allowed for lots of airflow and natural light. She included features like shuttered windows and skylights. Gray's kitchen had different levels, which was influenced by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky's Frankfurt Kitchen.

Le Corbusier often stayed at E-1027. Even though he admired the house, in 1938-1939, he painted murals on its walls without permission. This went against Eileen Gray's clear wish that E-1027 should have no decorations. One of his drawings, Three Women, showed Eileen and Jean together.

The house E-1027 has had several owners, including friends of Le Corbusier. Architect Renaud Barrés is the current owner.

World Wars: How Did Wars Affect Eileen Gray's Work?

In 1919, an exhibition called the 10th Salon des Artistes Decorateurs showed affordable furniture made after the war. The goal was to help rebuild Paris and heal the country from the war's damage. Many artists tried to show that Paris was still the "intellectual capital of the world." During this time, there was a strong push for modern designs. This exhibition aimed to promote new French art and compete with German designers. Eileen Gray took part in this exhibition, but her specific works were not recorded. In 1920, a magazine article about Gray's lacquer work stated, "Lacquer Walls and Furniture Displace Old Gods in Paris and London."

During World War II, Eileen Gray was held as a foreign national. Her houses were robbed. Many of her drawings, models, architectural notes, and personal papers were destroyed by bombing. German soldiers even used the walls of E-1027 for target practice.

Later Life: What Happened to Eileen Gray in Her Old Age?

People started to show new interest in Eileen Gray's work in 1967. This happened when historian Joseph Rykwert wrote an essay about her in an Italian design magazine. After the article was published, many students started visiting her, eager to learn from the now famous designer.

In 1972, at an auction in Paris, fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent bought a piece called Le Destin. This purchase brought even more attention to Eileen Gray's career.

The first major exhibition of her work, called Eileen Gray: Pioneer of Design, was held in London in 1972. A Dublin exhibition followed the next year. At the Dublin exhibit, the 95-year-old Gray was given an honorary award by the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland.

In 1973, Eileen Gray signed a contract to make copies of her Bibendum chair and many other pieces for the first time. This was with Aram Designs Ltd, London. These designs are still made today.

Eileen Gray passed away on Halloween in 1976. She is buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris. However, her family did not pay the license fee, so her grave cannot be identified.

Personal Life: What Was Eileen Gray Like?

Eileen Gray was known to be friends with many creative people of her time. She was associated with artists like Romaine Brooks, Loie Fuller, and singer Marie-Louise Damien.

Gray also had a working relationship with Jean Badovici, the Romanian architect and writer. He wrote about her design work in 1924 and encouraged her interest in architecture. Their close collaboration ended in 1932.

Even though she never lived in Ireland as an adult, she reportedly said in her old age, "I am without roots, but if I have any, they are in Ireland."

Posthumous Recognition: How Is Eileen Gray Remembered Today?

Eileen Gray's achievements were not fully recognized during her lifetime. According to one expert, her work was "too rich" for critics to understand at the time. If critics didn't write about you, especially in the big books of the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, you were often forgotten.

The National Museum of Ireland has a permanent exhibition of her work. You can see it at the Collins Barracks site.

In February 2009, Eileen Gray's "Dragons" armchair was sold at an auction in Paris. She made this chair between 1917 and 1919. It was bought by her early supporter Suzanne Talbot and later became part of the Yves Saint Laurent collection. The chair sold for €21.9 million (about US$28.3 million). This set a new record for 20th-century decorative art sold at auction.

Several films have been made about Eileen Gray's life and work. Marco Orsini's documentary, Gray Matters, came out in 2014. A movie about her life by Mary McGuckian, The Price of Desire, opened in 2016. In 2020, a short film by Michel Pitiot, In Conversation with Eileen Gray, was based on an interview from 1973 that was never released.

See also

In Spanish: Eileen Gray para niños

In Spanish: Eileen Gray para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |