Romaine Brooks facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Romaine Brooks

|

|

|---|---|

Romaine Brooks, around 1894

|

|

| Born |

Beatrice Romaine Goddard

May 1, 1874 |

| Died | December 7, 1970 (aged 96) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting, portraiture |

| Movement | Symbolist, aesthetic |

| Spouse(s) |

John Ellingham Brooks

(m. 1903; div. 1904) |

| Partner(s) | Natalie Clifford Barney |

Romaine Brooks (born Beatrice Romaine Goddard; May 1, 1874 – December 7, 1970) was an American painter. She mostly worked in Paris, France, and Capri, Italy. Romaine was known for her portraits. She used a special color scheme with lots of gray tones. Brooks did not follow popular art styles like Cubism or Fauvism. Instead, she created her own unique look. She was inspired by artists like James McNeill Whistler. Romaine painted many different people, from everyday models to famous aristocrats. She is most famous for her paintings of women in more masculine clothing. Her self-portrait from 1923 is her most well-known work.

Even though her family was rich, Romaine had a tough childhood. Her father left the family, and her mother was not kind to her. Her brother also had mental health issues. Romaine herself said that her childhood made her whole life feel sad. She spent several years as a poor art student in Italy and France. But in 1902, her mother passed away, and Romaine inherited a lot of money. This wealth allowed her to paint whatever she wanted. She often painted people she knew well. These included the Italian writer Gabriele D'Annunzio, the Russian dancer Ida Rubinstein, and her partner of over 50 years, the writer Natalie Barney.

Some people thought Romaine stopped painting after 1925, but this is not true. She made many drawings in the 1930s. She used a special technique that was like "automatic drawing" before it became popular. She also spent time in New York City in the mid-1930s. There, she painted portraits of Carl Van Vechten and Muriel Draper. Many of her artworks are now missing, but old photos show that she kept painting. Her last known portrait was of Duke Uberto Strozzi in 1961.

Contents

Romaine Brooks's Life Story

Early Life and Learning

Beatrice Romaine Goddard was born in Rome, Italy. She was the youngest of three children. Her parents, Ella and Henry Goddard, were wealthy Americans. Her grandfather was a very rich coal miner. Romaine's parents divorced when she was young, and her father left the family. Romaine grew up in New York. When she was seven, her mother sent her to live with a poor family in New York City. Her mother then disappeared and stopped paying for her care. The family still looked after Romaine, even though they became poorer. Romaine was afraid to tell them where her grandfather lived. She worried she would be sent back to her mother. Other records show she went to a girls' school in New Jersey, an Italian convent, and a Swiss finishing school.

After the foster family found her grandfather, he sent Romaine to study. She spent several years at St. Mary's Hall. This was an Episcopal girls' boarding school in Burlington, New Jersey. Later, she went to a convent school. This was between times spent with her mother, who moved around Europe a lot. Romaine later described her childhood as very difficult.

In 1893, when she was 19, Romaine left her family and went to Paris. She got a small amount of money from her mother. She took singing lessons and sang in a cabaret for a while. Later, she traveled to Rome to study art. Romaine was the only female student in her art class that drew from live models.

In the summer of 1899, Romaine rented a studio in the poorest part of the island of Capri. She still did not have enough money. After several months of almost starving, she became very sick. In 1901, she returned to New York when her brother passed away. Her mother died less than a year later. Romaine was 28 when she and her sister inherited a large amount of money from their grandfather. This made them very rich.

Personal Life

On June 13, 1903, Romaine married her friend John Ellingham Brooks. She then became a British citizen. John was a musician and translator who had money problems. They started arguing almost right away. Romaine cut her hair short and ordered men's clothes for a trip. John did not want to be seen with her dressed like that. She did not like his desire for proper appearances. She left him after only one year and moved to London. John kept talking about "our" money, which worried her. The money was her inheritance, not his. After they separated, she continued to give John money each year. He lived comfortably in Capri until he passed away in 1929.

Her Art Career

In 1904, Romaine was not happy with her artwork. She especially disliked the bright colors she used in her early paintings. She traveled to St. Ives on the Cornish coast. There, she rented a small studio. She began to learn how to use different shades of gray. When local artists asked her to show her work, she only displayed cardboard pieces. On these, she had experimented with gray paint. From then on, almost all her paintings used a gray, white, and black color scheme. She added small touches of other colors like brown, red, and blue-green. By 1905, she had found her unique color style. She continued to develop this look throughout her career.

First Art Show

Romaine left St. Ives and moved to Paris. Young artists like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse were creating new art in the bohemian areas of Montparnasse and Montmartre. But Romaine chose a different path. She took an apartment in the fancy 16th arrondissement. She spent time with wealthy and important people. She painted portraits of rich and titled women. This included her partner at the time, the Princess de Polignac.

In 1910, Romaine had her first solo art show. It was at the famous Gallery Durand-Ruel. She showed thirteen paintings, mostly of women or young girls. Some were portraits. Others showed models in indoor scenes or against simple backgrounds. They often had thoughtful or quiet expressions. The paintings looked very real. They showed great attention to the details of Belle Époque fashion. Things like parasols, veils, and fancy bonnets were clearly seen.

This exhibition made Romaine famous as an artist. Reviews were very positive. The poet Robert de Montesquiou wrote a special piece about her. He called her "the thief of souls." Her home's simple, almost single-color style also got attention. People often asked her for advice on decorating. She sometimes helped, but she did not enjoy being a decorator. Romaine became less and less happy with high society in Paris. She found the conversations boring and felt people were talking about her.

Friends and Inspirations

In 1909, Romaine met Gabriele D'Annunzio. He was an Italian writer and politician who came to France to avoid his debts. She saw him as a troubled artist. He wrote poems inspired by her paintings. He called her "the most profound and wise orchestrator of grays in modern painting."

In 1911, Romaine started a romantic relationship with Ida Rubinstein. Ida was a Ukrainian-Jewish actress and dancer. She was very famous and caused a stir with Serge Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. D'Annunzio also liked Rubinstein, but she did not feel the same way about him. Rubinstein was deeply in love with Romaine. She wanted to buy a farm where they could live together. Romaine, however, was not interested in that kind of life.

Even though they broke up in 1914, Romaine painted Rubinstein more than anyone else. For Romaine, Rubinstein's "delicate and androgynous beauty" was perfect for her art.

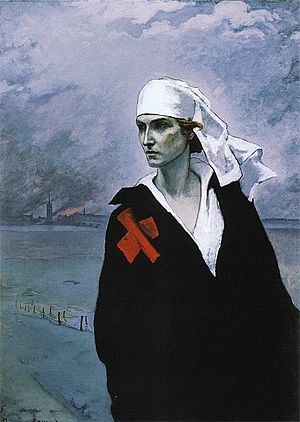

At the start of World War I, Romaine painted The Cross of France. This painting showed France during the war. It featured a Red Cross nurse looking determined. In the background, the city of Ypres was burning. The nurse in the painting looked like Rubinstein, and she might have posed for it. The painting was shown with a poem by D'Annunzio. The poem called for bravery during wartime. Later, it was printed in a booklet sold to raise money for the Red Cross. After the war, Romaine received the Legion of Honor award for her fundraising.

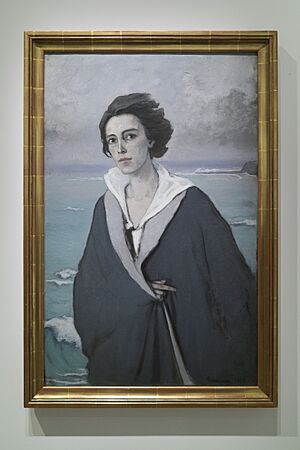

The strong image in The Cross of France has been compared to Eugène Delacroix's painting Liberty Leading the People. In Delacroix's painting, a woman representing Liberty holds a flag with a burning city behind her. Delacroix's Liberty leads a group of people fighting. But the woman in The Cross of France stands alone. Romaine used this idea of a hero standing alone in her 1912 portrait of D'Annunzio and her 1914 self-portrait. The people in these paintings are wrapped in dark cloaks and stand alone against ocean scenes.

Romaine's political views are sometimes unclear because of her friendship with D'Annunzio. He was seen as a leader who inspired some later political movements. However, there is no proof that Romaine supported these movements. Her paintings often showed strong, individual people. This style might have been influenced by D'Annunzio's ideas about art.

In 2016, a young Italian researcher found an early painting by Romaine. It was at the Vittoriale in Gardone. Romaine had copied Perugino's Portrait of a Young Man when she was a poor art student in Rome. She painted the man because she thought he looked like her as a girl. She later gave the painting to D'Annunzio as a joke. She did not like that D'Annunzio often hung pictures of his partners in a special gallery. This painting was found in the music room.

D'Annunzio and Romaine spent the summer of 1910 in a villa in France. Their time was interrupted when one of D'Annunzio's former partners came to the villa with a pistol. She demanded to be let in. After a short disagreement, Romaine and D'Annunzio remained friends until his death in Italy.

Romaine painted Rubinstein one last time in The Weeping Venus (1916–1917). Romaine wrote that the painting showed "the passing away of familiar gods" because of World War I. She said she tried to repaint Venus's face many times, but Rubinstein's face kept appearing. She said, "It fixes itself in the mind."

Natalie Barney and Left Bank Portraits

The longest and most important relationship in Romaine's life was with Natalie Clifford Barney. Natalie was an American writer. They also shared a friendship with Lily de Gramont, a French noblewoman.

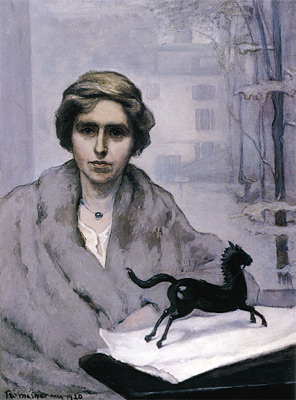

Romaine's portrait of Natalie Barney looks softer than her other paintings from the 1920s. Natalie sits wrapped in a fur coat. She is in the house where she lived and held her famous gatherings. Outside the window, the courtyard is covered in snow. Romaine often included animals or animal sculptures in her paintings. These helped show the personalities of the people she painted. She painted Natalie with a small horse sculpture. This was a nod to Natalie's love of riding, which earned her the nickname "the Amazon." The paper under the horse might be one of Natalie's writings.

From 1920 to 1924, most of Romaine's subjects were women who were part of Natalie Barney's social group.

Several of these paintings show women who wore some men's clothing. In 1903, Romaine had surprised her husband by cutting her hair short and ordering a men's suit. By the mid-1920s, short hairstyles were popular for women. Wearing tailored jackets, usually with a skirt, was also a recognized fashion. It was called the "severely masculine" look.

Gluck, an English artist, was painted by Romaine around 1923. Gluck was known for her unique style of dress as much as for her art. She wore trousers all the time, which was not common for women in the 1920s. Articles about her said her way of dressing was an artistic choice or a sign that she was very modern.

Romaine's 1923 self-portrait has a serious mood. Romaine, who also designed her own clothes, painted herself in a tailored riding coat, gloves, and a top hat. Behind her is a ruined building, painted in gray and black, under a dark sky. The only bright colors are her lipstick and the red ribbon of the Legion of Honor. This ribbon reminds us of the Red Cross symbol in The Cross of France. Her eyes are hidden by her hat. One art expert said, "she's watching you before you get close enough to look at her. She's not passively inviting your approach; she's deciding whether you're worth bothering with."

Later Art and Life

In 1925, Romaine had solo art shows in Paris, London, and New York. There is no proof that she stopped painting after 1925. While in New York in the 1930s, she painted portraits of Carl Van Vechten in 1936 and Muriel Draper in 1938. We also know she bought paints during World War II when she and Natalie were in Florence. Photos show that there are still some of Romaine's lost artworks waiting to be found. Romaine completed what was thought to be her last portrait in 1961, when she was 87. The artist said she had drawn all her life. In a 1968 interview, she said she was annoyed that a portrait of her showed dried-up brushes. She said, "As if I didn't paint." Her comments suggest she was still very much a painter. She had even planned to paint a portrait of the artist who painted her, but he never had time to pose.

Romaine was a model for the painter Venetia Ford in Radclyffe Hall's novel The Forge (1924). She also appeared in Compton Mackenzie's Extraordinary Women (1928) as the musician Olympia Leigh. In Djuna Barnes's Ladies Almanack (1928), she briefly appears as Cynic Sal.

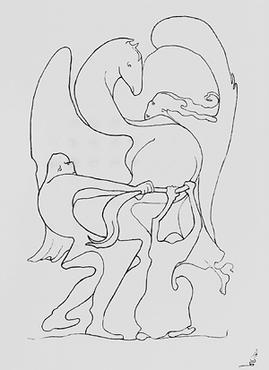

Drawings and Later Years

From the 1930s onward, Romaine's work was mostly forgotten. In 1930, while recovering from a leg injury, Romaine started a series of over 100 drawings. These drawings showed humans, angels, demons, animals, and monsters. All were made with continuous curved lines. She said that when she started a line, she did not know where it would go. She said the drawings "evolve[d] from the subconscious...[w]ithout premeditation." Romaine was writing her life story, No Pleasant Memories, at the same time she began these drawings. Experts believe these drawings show how her childhood continued to affect her. The symbol she used to sign them, a wing on a spring, also suggests this. Decades later, at 85, she said, "My dead mother gets between me and life."

Many writers thought Romaine stopped painting, but she said she drew all her life. She moved from Paris to Villa Sant'Agnese, a villa outside Florence, Italy, in 1937. In 1940, Natalie Barney joined her there to escape the German invasion of France. After World War II ended, Romaine did not want to move back to Paris with Natalie. She said she wanted to "get back to [her] painting and painter's life." However, she mostly stopped making art after the war. She and Natalie worked to promote her art and get her paintings into galleries and museums. Romaine became more and more private. While Natalie visited her often, by the mid-1950s, Natalie had to stay in a hotel. They would only meet for lunch. Romaine spent weeks in a dark room, thinking she was losing her eyesight. She became very worried, fearing someone was stealing her drawings or that her driver planned to harm her. In the last year of her life, she stopped talking to Natalie completely. She left letters unanswered and refused to open the door when Natalie visited. She passed away in Nice, France, in 1970, at the age of 96. Romaine Brooks is buried in the old English Cemetery in Nice, with her mother and brother.

Art Influences

Romaine kept her distance from the popular art styles of her time. She acted "as if the Fauvists, the Cubists, and the Abstract Expressionists did not exist." Some critics wrongly said Romaine was influenced by Aubrey Beardsley's drawings. Romaine herself denied this in a 1968 interview. Her drawings from the 1930s continued her experiments with dream-like art. She started these experiments as a teenager in the late 1880s. Her use of "unplanned" drawings to explore her subconscious has been compared to "automatic drawings" by Surrealist artists of the 1920s. But Romaine's work came decades before artists like André Masson. One artist even called her the first Surrealist.

The biggest influence on Romaine's painting was James McNeill Whistler. His quiet color palette likely inspired her to use mostly one color with small touches of other shades. This technique helped her create a classic, calm feeling. It also allowed her to show tension through shapes, textures, and different shades in her paintings. She might have learned about Whistler's work from art collector Charles Lang Freer. She met him in Capri around 1899, and he bought one of her early works. Romaine said she "wondered at the magic subtlety of [Whistler's] tones." But she thought his "symphonies" lacked deep expression. One of her 1920 portraits might have been inspired by a Whistler painting. The poses are almost the same. But Romaine removed the little girl and all the details of Whistler's home scene. She left only the musician Borgatti and her piano. This showed an artist completely focused on her music.

Her Legacy in Art

Romaine's realistic art style might have caused many art critics to ignore her. By the 1960s, her work was mostly forgotten. But since the 1980s, realistic painting has become popular again. This has led to a new appreciation for her work. She is now seen as an artist who explored themes of gender variance and transgender identity before it was widely discussed.

Romaine's portraits, starting with her 1914 self-portrait and including The Cross of France, are seen as creating new images of strong women. Her portraits from the 1920s especially show women as powerful, confident, and brave. One critic compared their faces to those on Mount Rushmore. Romaine seemed to see her portraits this way too. According to Natalie Barney, one woman complained after seeing her portrait, "You haven't made me beautiful." Romaine replied, "I have made you noble."

Romaine did not always make her subjects look noble. Her inherited wealth meant she did not need to sell her paintings. She did not care if she pleased the people she painted. Her sharp wit could be very strong. A good example is her 1914–1915 portrait of Elsie de Wolfe. Elsie was an interior designer whom Romaine felt had copied her color schemes. Romaine painted Elsie very pale, in an off-white dress and a hat that looked like a shower cap. A white ceramic goat on a table next to her seemed to copy Elsie's overly sweet expression.

One of Romaine's most discussed paintings is a 1924 portrait of Una, Lady Troubridge. This painting has been seen in many ways. Some see it as an image of female strength. Others see it as a funny drawing. Art critic Michael Duncan thinks the painting makes fun of Troubridge's "fancy appearance." For Meryle Secrest, it is "a great example of ironic comment." Laura Doan points out that newspapers and magazines from 1924 described high collars, tailored satin jackets, and watch fobs as the latest women's fashion. She says Troubridge had a "sharp fashion sense and an eye for clothing details." But these British fashions might not have been popular in Paris. Natalie Barney and others thought Troubridge's outfits were silly. Romaine shared her own view in a letter to Natalie: "Una is funny to paint. Her outfit is remarkable. She will live perhaps and cause future generations to smile."

In 2016, Smithsonian magazine featured an exhibition of Romaine Brooks's art. They said, "The world is finally ready to understand Romaine Brooks."

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Romaine Brooks para niños

In Spanish: Romaine Brooks para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |