Natalie Clifford Barney facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Natalie Clifford Barney

|

|

|---|---|

Barney in 1898, photograph by Alice Hughes

|

|

| Born | October 31, 1876 Dayton, Ohio, US

|

| Died | February 2, 1972 (aged 95) Paris, France

|

| Burial place | Passy Cemetery |

| Known for |

|

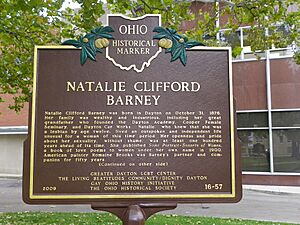

Natalie Clifford Barney (born October 31, 1876 – died February 2, 1972) was an American writer. She was famous for hosting a special gathering called a "literary salon" at her home in Paris. This salon brought together many French and international writers.

Natalie Barney influenced other authors through her salon and with her own writing. She wrote poems, plays, and short, clever sayings called epigrams. Her works often explored her belief in women's rights and her love for women.

Barney came from a rich family. She studied partly in France and wanted to live openly as a lesbian from a young age. She moved to France with her first close friend, Eva Palmer. Inspired by the ancient poet Sappho, Barney started publishing love poems to women under her own name in 1900. She wrote in both French and English and supported women's rights and peace. She believed in having many relationships at once.

Barney hosted her salon in Paris for more than 60 years. It was a place where writers and artists from all over the world could meet and share ideas. Many important figures in French, American, and British literature attended. People felt comfortable expressing themselves at these weekly gatherings. Barney worked hard to promote writing by women. She even started a "Women's Academy" (L'Académie des Femmes) at her salon. This was her way of responding to the all-male French Academy.

The salon closed during World War II while Barney lived in Italy. She initially had some views that supported fascism, but by the end of the war, she supported the Allies. After the war, she returned to Paris and reopened her salon. She continued to inspire writers like Truman Capote.

Natalie Barney had a big impact on literature. The French writer Remy de Gourmont called her l'Amazon (the Amazon) in his public letters. This nickname stayed with her for the rest of her life. Her life and relationships also inspired many novels written by others.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Natalie Barney was born in 1876 in Dayton, Ohio. Her parents were Albert Clifford Barney and Alice Pike Barney. Her mother, Alice, loved the arts, learning from her own father who owned an opera house. Her father, Albert, inherited part of his family's railroad car manufacturing company.

When Natalie was five, she met the famous writer Oscar Wilde in a New York hotel. Wilde picked her up and told her a story. The next day, he joined Natalie and her mother at the beach. Wilde inspired Alice to seriously pursue art, even though her husband did not approve.

Like many girls of her time, Barney's education was not always planned. She became interested in French because her governess read Jules Verne stories aloud to her. She had to learn French quickly to understand them. Natalie and her younger sister Laura went to Les Ruches, a French boarding school in Fontainebleau, France. It was started by a woman who supported women's rights, Marie Souvestre. As an adult, Natalie spoke and wrote French very well.

When she was ten, her family moved from Ohio to Washington D.C. They spent summers at their large cottage in Bar Harbor, Maine. Natalie was a rebellious and unusual daughter from one of the richest families in town. She was often mentioned in Washington newspapers. In her early twenties, she made headlines by riding a horse through Bar Harbor while leading another horse. She rode astride (like men) instead of sidesaddle (like most women).

Barney later said she knew she was a lesbian by age twelve. She was determined to "live openly, without hiding anything."

Early Relationships

Eva Palmer

Natalie Barney's first close relationship was with Eva Palmer. They met during summer vacations in Bar Harbor, Maine, and started a relationship in 1893. They remained close for several years. As young adults in Paris, they shared an apartment. Barney often asked Palmer for help with her relationships with other women. Palmer eventually moved to Greece and married Angelos Sikelianos. This caused their relationship to end for a while, but they became friends again later through letters and meetings in New York.

Liane de Pougy

In 1899, Barney met Liane de Pougy in Paris. De Pougy was one of the most famous women in France. Barney was very bold and charming, which impressed de Pougy.

Barney was set to inherit family money if she married or waited for her father's death. While she was with de Pougy, Barney was also engaged to Robert Cassat, from another wealthy family. Barney was open with Cassat about her feelings for women and her relationship with de Pougy. The three even thought about a quick wedding between Barney and Cassat, and then adopting de Pougy, to get Barney's money. But Cassat ended the engagement.

By the end of 1899, Barney and de Pougy had broken up. However, they continued their relationship on and off for many years.

Their on-and-off relationship became the subject of a famous book by de Pougy, called Idylle Saphique (Sapphic Idyll). Published in 1901, the book was reprinted more than 70 times in its first year and was widely discussed in Paris. Barney soon became known as the person one of the characters was based on.

Barney herself wrote a chapter for Idylle Saphique. In it, she compared the struggles of the character Hamlet to those of women. She wrote, "What is there for women who feel the passion for action when pitiless Destiny holds them in chains? Destiny made us women at a time when the law of men is the only law that is recognized." She also wrote Lettres à une Connue (Letters to a Woman I Have Known), her own novel about the relationship. Although she couldn't find a publisher for it, the book is important for its discussion of love between women. Barney believed it was natural and harmless.

Renée Vivien

In November 1899, Barney met the poet Pauline Tarn, known as Renée Vivien. For Vivien, it was love at first sight. Barney became fascinated with Vivien after hearing her read a poem. Their relationship also helped both of them write more. Barney gave Vivien ideas about women's rights, which Vivien explored in her poems. They used old poetic styles to describe love between women. They also found examples of brave women in history and myths. Sappho was a very important influence, and they studied Greek to read her poems in their original form. Both wrote plays about Sappho's life.

Vivien saw Barney as a muse, someone who inspires art. Barney felt Vivien saw her as a femme fatale, a charming woman who leads men to trouble. Vivien also believed in having only one partner, but Barney did not. While Barney was visiting her family in Washington, D.C. in 1901, Vivien stopped answering her letters. Barney tried to win her back for years.

In 1904, Barney wrote Je Me Souviens (I Remember), a very personal poem about their relationship. She gave it to Vivien as a handwritten copy to try and win her back. They made up and traveled to Lesbos. They lived happily there for a short time and talked about starting a poetry school for women, like the one Sappho was said to have founded. However, Vivien soon got a letter from another lover, Baroness Hélène van Zuylen, and went to Istanbul. Vivien planned to meet Barney in Paris afterward, but she stayed with the Baroness instead. This time, their breakup was permanent.

Vivien's health quickly got worse after this. She died in 1909.

In 1949, Barney helped bring back the Renée Vivien Prize for women writers. She became the head of the jury in 1950.

Olive Custance

In 1900, Barney read Opals, a book of poems by Olive Custance. Because the poems had themes of love between women, Barney started writing to Custance and exchanging poems. They met in 1901 at Barney and Vivien's home in Paris and soon began a short relationship. Custance was also in a relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas, whom she later married.

Poetry and Plays

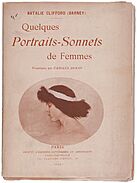

In 1900, Barney published her first book, a collection of poems called Quelques Portraits-Sonnets de Femmes (Some Portrait-Sonnets of Women). The poems were written in a traditional French style. This book was important because Barney was the first woman poet since Sappho to openly write about the love of women. Her mother drew pictures for the poems, not knowing that three of the four women she drew were her daughter's lovers.

Reviews were mostly good and didn't focus on the poems' themes of love between women. Some even misunderstood it. However, a newspaper headline said "Sappho Sings in Washington," which alerted her father. He bought and destroyed all the remaining copies and printing plates of the book.

To avoid her father's control, Barney published her next book, Cinq Petits Dialogues Grecs (Five Short Greek Dialogues, 1901), using the pen name Tryphé. The first dialogue is set in ancient Greece and describes Sappho. Another part argues for paganism over Christianity. After Barney's father died in 1902, she inherited a large amount of money. This freedom meant she no longer needed to hide that she wrote her books. She never used a pen name again. She thought scandal was "the best way of getting rid of nuisances" (meaning unwanted attention from young men).

Je Me Souviens was published in 1910, after Vivien's death. That same year, Barney published Actes et Entr'actes (Acts and Interludes), a collection of short plays and poems. One of the plays was Équivoque (Ambiguity). This play told a different version of Sappho's death. Instead of jumping off a cliff for a sailor, Sappho does so because she is sad that the sailor is marrying the woman she loves. The play included parts of Sappho's original poems and was performed with ancient Greek-inspired music and dance.

Barney didn't take her poetry as seriously as Vivien did. She once said, "if I had one ambition it was to make my life itself into a poem." Her plays were only performed by amateurs in her garden. Most of them didn't have clear plots. After 1910, she mostly wrote epigrams and memoirs, which she is more known for. Her last poetry book was Poems & Poemes: Autres Alliances in 1920. It contained romantic poems in both French and English.

The Salon Gatherings

For over 60 years, Natalie Barney hosted a literary salon. It was first held in Neuilly, but mostly at her home at 20, Rue Jacob, in Paris. Her salon was a weekly gathering on Fridays where people met to socialize and talk about literature, art, music, and other interesting topics. Even though she hosted some of the most famous male writers of her time, Barney worked hard to highlight female writers and their work.

Barney's salon was also special because it was very international. She brought together expatriate (people living outside their home country) Modernists with members of the French Academy.

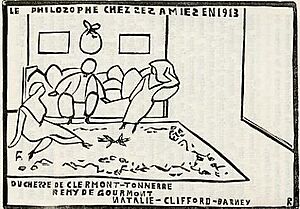

In the early 1900s, Barney held salon gatherings at her house in Neuilly. The entertainment included poetry readings and plays. The famous dancer Mata Hari even performed a dance once, riding into the garden on a white horse. The play Equivoque might have caused Barney to leave Neuilly in 1909. A newspaper article at the time said her landlord didn't like her outdoor performance of a play about Sappho. She moved to a small two-story house with a large garden in Paris's Latin Quarter. Her salon was held there until the late 1960s. In this new place, the salon became more formal, with poetry readings and conversations. Regular guests during this time included poets Pierre Louÿs and Paul Claudel.

During World War I, the salon became a safe place for those who were against the war. Henri Barbusse read from his anti-war novel Under Fire. Barney also hosted a Women's Congress for Peace. Other visitors during the war included Oscar Milosz and Auguste Rodin.

Ezra Pound was a close friend of Barney's and visited often. They planned to help writers Paul Valéry and T. S. Eliot so they could quit their jobs and focus on writing. Pound also introduced Barney to the composer George Antheil. Barney hosted the first performances of some of Antheil's music at her salon. It was also at Barney's salon that Pound met his longtime partner, the violinist Olga Rudge.

In 1927, Barney started an Académie des Femmes (Women's Academy) to honor women writers. This was her response to the famous Académie Française (French Academy), which had no women members at the time. Unlike the French Academy, Barney's was not a formal group. It was a series of readings held during her regular Friday salons. Honored writers included Colette, Gertrude Stein, and Renée Vivien (after her death). The academy's activities slowed down after 1927.

Other visitors to the salon in the 1920s included French writers like André Gide and Jean Cocteau. English-language writers also visited, such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and T. S. Eliot. Barney also hosted German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, and Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore (the first Nobel Prize winner from Asia). Famous people like Sylvia Beach (who published James Joyce's Ulysses), and the painter Tamara de Lempicka also came.

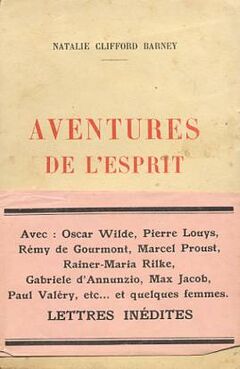

For her 1929 book Aventures de l'Esprit (Adventures of the Mind), Barney drew a map showing over a hundred people who had attended the salon. The book included memories of 13 male writers she had known and a chapter for each member of her Académie des Femmes.

In the late 1920s, Radclyffe Hall read from her novel The Well of Loneliness, which had recently been banned in the UK. A reading by poet Edna St. Vincent Millay filled the salon in 1932.

Of the famous Modernist writers in Paris, Ernest Hemingway never came to the salon. James Joyce visited once or twice but didn't like it. Marcel Proust never attended a Friday salon, but he did come once to talk with Barney about lesbian culture for his research.

Epigrams and Novel

Éparpillements (Scatterings, 1910) was Barney's first collection of pensées—short, clever thoughts. This type of writing had been popular in French salons since the 1600s. Barney's pensées were often one-line sayings, like "There are more evil ears than bad mouths."

Her writing career got a boost after she sent a copy of Éparpillements to Remy de Gourmont. He was a French poet and critic who had become a recluse. He was so impressed that he invited her to his Sunday gatherings, where he usually only saw a few old friends. She brought new energy into his life. He turned some of their conversations into letters that he published, calling her l'Amazone (the Amazon). These letters were later put into a book. He died in 1915, but the nickname stayed with her. Her tombstone even calls her "the Amazon of Remy de Gourmont." His letters made readers want to know more about the woman who inspired them.

Barney responded in 1920 with Pensées d'une Amazone (Thoughts of an Amazon), her most political work. The One Who is Legion, or A.D.'s After-Life (1930) was Barney's only book written entirely in English, and her only novel.

Later Life and Legacy

Barney's views during World War II have been discussed. She had Jewish heritage. She spent the war in Florence, Italy, and was investigated by Italian authorities because of her background. She was able to avoid trouble after her sister arranged a document proving her confirmation.

She believed some propaganda that said the Allies were the aggressors. So, supporting fascism seemed logical to her because she was a pacifist (someone who believes in peace and is against war). An unpublished memoir she wrote during the war years shows some pro-Fascist and anti-Semitic (anti-Jewish) views.

It's possible these anti-Semitic parts were meant to show she wasn't Jewish. Or, she might have been influenced by Ezra Pound's anti-Semitic radio broadcasts. However, she did help a Jewish couple escape Italy by providing them passage on a ship to the United States. By the end of the war, her feelings had changed, and she saw the Allies as liberators.

After the war, her partner Brooks chose to stay in Italy, and they visited each other often. Their relationship remained mostly exclusive until the mid-1950s. Then, Barney met her last new love, Janine Lahovary. Lahovary became friends with Brooks, and Barney assured Brooks that their relationship was still most important.

The salon reopened in 1949 and continued to attract young writers. Truman Capote was a guest for almost ten years. He said the decor was "totally turn-of-the-century" and remembered that Barney introduced him to people who inspired characters in Marcel Proust's famous novel.

Alice B. Toklas became a regular after her partner Gertrude Stein died in 1946. In the 1960s, the Friday salons honored Mary McCarthy and Marguerite Yourcenar. Yourcenar later became the first female member of the French Academy in 1980, eight years after Barney's death.

Barney didn't write epigrams again, but she published two books of memoirs about other writers she had known: Souvenirs Indiscrets (Indiscreet Memories, 1960) and Traits et Portraits (Traits and Portraits, 1963). She also worked to find a publisher for Brooks's memoirs and to get her paintings into galleries.

In the late 1960s, Brooks became more withdrawn and sad. She refused to see doctors. She was upset about Lahovary's presence during their last years, which she had hoped to spend only with Barney. Brooks finally stopped talking to Barney. Barney continued to write to her, but received no replies. Brooks died in December 1970, and Barney died on February 2, 1972, at age 95, from heart failure. She is buried at Passy Cemetery in Paris, France. She left some of her writings, including over 40,000 letters, to a library in Paris.

Legacy

By the end of Natalie Barney's life, her work had been mostly forgotten. In 1979, Barney was honored with a place setting in Judy Chicago's feminist artwork The Dinner Party. In the 1980s, Barney began to be recognized for how much her ideas were similar to those of later feminist writers. English translations of some of her memoirs, essays, and epigrams appeared in 1992, but most of her plays and poetry have not been translated.

Works

In French

- Quelques Portraits-Sonnets de Femmes (Paris: Ollendorf, 1900)

- Cinq Petits Dialogues Grecs (Paris: La Plume, 1901; as "Tryphé")

- Actes et entr'actes (Paris: Sansot, 1910)

- Je me souviens (Paris: Sansot, 1910)

- Eparpillements (Paris: Sansot, 1910)

- Pensées d'une Amazone (Paris: Emile Paul, 1920)

- Aventures de l'Esprit (Paris: Emile Paul, 1929)

- Nouvelles Pensées de l'Amazone (Paris: Mercure de France, 1939)

- Souvenirs Indiscrets (Paris: Flammarion, 1960)

- Traits et Portraits (Paris: Mercure de France, 1963)

- Amants féminins ou la troisième (Paris: ErosOnyx, 2013)

In English

- Poems & Poèmes: Autres Alliances (Paris: Emile Paul, New York: Doran, 1920) – bilingual collection of poetry

- The One Who Is Legion (London: Eric Partridge, Ltd., 1930; Orono, Maine: National Poetry Foundation, 1987) facsimile reprint with an afterword by Edward Lorusso

English translations

- A Perilous Advantage: The Best of Natalie Clifford Barney (New Victoria Publishers, 1992); edited and translated by Anna Livia

- Adventures of the Mind (New York University Press, 1992); translated by John Spalding Gatton

- Women Lovers, or The Third Woman (University of Wisconsin Press, 2016); edited and translated by Chelsea Ray

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Natalie Clifford Barney para niños

In Spanish: Natalie Clifford Barney para niños

- LGBT culture in Paris

- Renée Vivien Prize

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |