Elsie de Wolfe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elsie de Wolfe

|

|

|---|---|

Elsie de Wolfe, 1914

|

|

| Born |

Ella Anderson de Wolfe

December 20, c. 1859 New York City, U.S.

|

| Died | July 12, 1950 (aged 90) Versailles, France

|

| Occupation |

|

| Title | Lady Mendl |

| Spouse(s) |

Sir Charles Mendl

(m. 1926) |

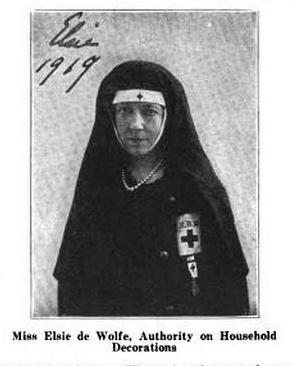

Elsie de Wolfe, Lady Mendl (born Ella Anderson de Wolfe; December 20, c. 1859 – July 12, 1950) was an American actress. She became a very famous interior designer and writer. Elsie de Wolfe was born in New York City. From a young age, she noticed everything around her. She became one of the first women to work as an interior decorator. She changed dark, fancy Victorian styles to lighter, simpler looks. Her designs made rooms feel open and tidy.

In 1926, she married an English diplomat named Sir Charles Mendl. Their marriage was seen as a practical arrangement. Even so, she was proud to be called Lady Mendl. Her close friend was Elisabeth Marbury, and they lived together in New York and Paris. Lady Mendl was a well-known person in society. She hosted parties for important people.

Contents

Elsie de Wolfe's Career

Many people say that Elsie de Wolfe created the job of "interior design." She was the most famous person in this field until the 1930s. But the job of interior decorator was already growing by 1900. This was five years before she got her first big project. That project was the Colony Club in New York. After she married in 1926, the newspapers often called her Lady Mendl.

Elsie de Wolfe worked for many important clients. These included Anne Harriman Vanderbilt and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. She also designed for Henry Clay and Adelaide Frick. She changed their homes from dark, heavily decorated places. She made them into bright, cozy spaces. She used fresh colors and furniture from 18th-century France. In 1913, she wrote an important book called The House in Good Taste.

In her own life story, Elsie de Wolfe called herself a "rebel in an ugly world." She was the only daughter of a Canadian doctor. She was very sensitive to style and color even as a child. One day, she came home from school and saw her parents had changed the living room.

She ran in and saw the walls. They had new wallpaper with a Morris design. It had gray palm-leaves and bright red and green spots on a dull tan background. Something terrible hurt her inside. She fell to the floor, kicking and hitting the carpet. She kept crying, "It's so ugly! It's so ugly!"

Hutton Wilkinson, who leads the Elsie de Wolfe Foundation, explained this. He said that many things Elsie de Wolfe disliked, like "pickle and plum Morris furniture," are now valued by museums. Wilkinson wrote that de Wolfe simply did not like the Victorian style. This was the main style of her sad childhood. So, she decided to remove it from her design work.

Becoming an Actress

Elsie de Wolfe first wanted to be an actress. She started with the Amateur Comedy Club in New York City. She acted in A Cup of Tea in April 1886. She also played in Sunshine in December 1886. Her success led her to become a full-time actress. She made her professional debut in Sardou's Thermidor in 1891.

In 1894, she joined the Empire Stock Company. In 1901, she put on The Way of the World herself. She later toured the United States in this role. As an actress, she was not a huge failure or a great success. One critic said she was best at "wearing good clothes well." She became interested in decorating because of staging plays. In 1903, she left the theater to start a career as a decorator.

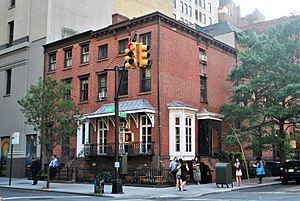

Many things helped her become famous in this new field. These included her social connections and her acting fame. Her success in decorating the Irving House also helped. This was the home she shared with her close friend, Elisabeth Marbury.

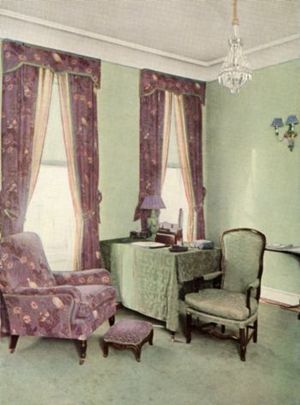

She preferred a brighter decorating style than was popular in Victorian times. She helped change homes with dark curtains and heavy furniture. She made them into light, soft, and more feminine rooms. She used mirrors a lot, which made rooms brighter and look bigger. She brought back painted furniture in white or light colors. She also loved chinoiserie, chintz, and green and white stripes. She used wicker, trompe-l'œil effects in wallpaper, and garden-like patterns. Elsie de Wolfe said, "I opened the doors and windows of America, and let the air and sunshine in." Her ideas came from 18th-century French and English art, books, theater, and fashion.

Designing the Colony Club

In 1905, Stanford White, an architect and old friend, helped Elsie de Wolfe. He helped her get the job to design the Colony Club. The club was at 120 Madison Avenue in New York. When it opened two years later, it became the most important women's social club. Much of its charm came from Elsie de Wolfe's designs.

Instead of the heavy, masculine style popular then, she used light fabrics for windows. She painted walls pale colors and tiled the floors. She added wicker chairs and sofas. The rooms felt like bright outdoor garden pavilions. (Today, the building is home to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts.) The success of the Colony Club changed her life and career. It made her the most wanted interior decorator of her time.

Over the next six years, Elsie de Wolfe designed many fancy homes, clubs, and businesses. She worked on both the East and West coasts. By 1913, her reputation grew so much that her studio took up a whole floor of offices on 5th Avenue. That year, she got her biggest job. It was from Henry Clay Frick, one of America's richest men.

Marriage and Personal Life

Elsie de Wolfe's marriage in 1926 was big news in New York Times. She married Sir Charles Mendl, a British diplomat in Paris. Their marriage was a practical arrangement. They seemed to have married mainly for social reasons. They entertained guests together but lived in separate homes. When Elsie de Wolfe wrote her life story in 1935, she did not mention her husband.

The Times reported that "the intended marriage comes as a great surprise to her friends." This hinted at the fact that since 1892, Elsie de Wolfe had lived with Bessie Marbury. First, they lived at 49 Irving Place. Later, they moved to 13 Sutton Place. The newspaper said, "When in New York she makes her home with Miss Elizabeth [sic] Marbury at 13 Sutton Place."

Elisabeth ("Bessie") Marbury was the daughter of a rich New York lawyer. Like Elsie de Wolfe, she was also a pioneering career woman. She was one of the first female theater agents. She was also one of the first women to produce plays on Broadway. Her clients included famous writers like Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw. For nearly 40 years, Marbury was the main support for the couple.

Public Image and Habits

In 1926, The New York Times called Elsie de Wolfe "one of the most widely known women in New York social life." In 1935, they said she was "prominent in Paris society."

In 1935, experts in Paris named her the best-dressed woman in the world. They noted that she wore what looked best on her, no matter what was in fashion.

Elsie de Wolfe had pillows with the saying "Never complain, never explain." When she first saw the Parthenon in Greece, she famously said, "It's beige — my color!"

At her house in France, the Villa Trianon, she had a special dog cemetery. Each tombstone there read, "The one I loved the best."

Diet and Exercise

In the early 1900s, Elsie de Wolfe promoted a semi-vegetarian diet. This diet included fresh fish, oysters, shellfish, and vegetables. She called herself an "antisarcophagist." This meant she did not eat red meat, but she was not fully vegetarian. De Wolfe also encouraged gardening and eating homegrown vegetables and organic food.

In her later years, Elsie de Wolfe became a vegetarian. Nutritionist Gayelord Hauser guided her. In 1974, Hauser said that "the fabulous Lady Mendl Elsie de Wolfe Mendl was a good friend and faithful student of nutrition, of whom I am very proud."

Her morning exercises were very famous. In her memoir, Elsie de Wolfe wrote about her daily routine at age 70. It included yoga, standing on her head, and walking on her hands. She said, "I have a regular exercise routine based on the Yogi method." She added, "I stand on my head [and] I can turn cart wheels. Or I walk upside-down on my hands." This part of her life was mentioned in the song "Anything Goes" by Cole Porter in 1934. The song says: "When you hear that Lady Mendl standing up/Now does a handspring landing up/on her toes/anything goes."

Elsie de Wolfe died in Versailles, France. Her body was cremated. Her ashes were placed in a common grave at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Tributes

In 2015, Equality Forum named her one of its 31 Icons for LGBT History Month.

See also

In Spanish: Elsie de Wolfe para niños

In Spanish: Elsie de Wolfe para niños

- The Decoration of Houses, a book about interior design by Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman

- Victorian decorative arts

- Ludwig Bemelmans, The one I loved the best (1955)

- The Great Lady Decorators: The Women Who Defined Interior Design, 1870–1955 by Adam Lewis (2010), Rizzoli, New York. ISBN: 978-0-8478-3336-8