Mahdist State facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mahdist State

الدولة المهدية

Al-Dawla al-Mahdiyah |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1885–1899 | |||||||||||

|

One of the flags of the Mahdi movement; most Mahdist flags varied in color but were similar to this one in their style.

|

|||||||||||

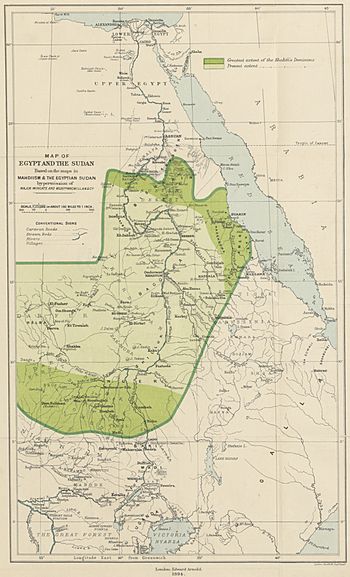

Mahdist Sudan's approximate territory in 1894 (light green) and approximate maximum limits (dark green).

|

|||||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized state | ||||||||||

| Capital | Omdurman | ||||||||||

| Common languages |

|

||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Islamic state | ||||||||||

| Mahdi | |||||||||||

|

• 1881–1885

|

Muhammad Ahmad | ||||||||||

| Khalifa | |||||||||||

|

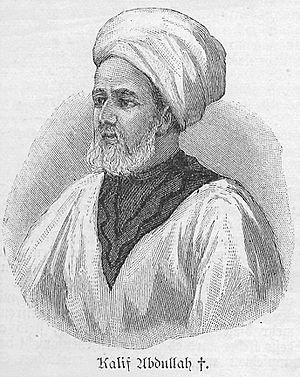

• 1885–1899

|

Abdallahi ibn Muhammad | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Shura council | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Scramble for Africa | ||||||||||

| 1881–1885 | |||||||||||

| 26 January 1885 | |||||||||||

|

• Sudan Convention

|

18 January 1899 | ||||||||||

| 24 November 1899 | |||||||||||

|

• Fall of Sanin Husain's holdout

|

1909 | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

|

• Pre-Mahdist

|

7,000,000 | ||||||||||

|

• Post-Mahdist

|

2,000,000–3,000,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency |

|

||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | SD | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Today part of | Sudan South Sudan |

||||||||||

The Mahdist State, also known as Mahdist Sudan, was a country in Africa. It was formed in 1885 after a religious and political uprising. This movement was started in 1881 by Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdullah. He was known as Muhammad al-Mahdi. His goal was to fight against the Egyptian government that had ruled Sudan since 1821.

After four years of fighting, the Mahdist rebels won. They took control from the Egyptian rulers. They set up their own "Islamic and national" government. Its capital city was Omdurman. The Mahdist government ruled Sudan from 1885 until 1898. That's when British and Egyptian forces ended its rule.

Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi called on the people of Sudan to join a jihad, or holy struggle. This was against the government in Khartoum, which was run by Egyptians and Turks. At first, the Khartoum government didn't take the Mahdi's uprising seriously. But he defeated two armies sent to capture him. The Mahdi's power grew, and his message spread across Sudan. His followers became known as the Ansar.

Around the same time, the British took control of Egypt in 1882. Britain then sent Charles George Gordon to be the governor of Sudan. After many battles with the Mahdi's rebels, Mahdist forces captured Khartoum. Gordon was killed in his palace. The Mahdi died soon after this victory. His successor, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, took over. He strengthened the new state. Its laws and government were based on their understanding of Islamic law. Some local Nubian Coptic Christians were pressured to change their religion to Islam.

The economy of Sudan was badly damaged during the Mahdist War. Famine, war, and disease caused the population to drop by half. Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi declared that people who did not accept him were non-believers. He ordered harsh treatment for them.

The British took back control of Sudan in 1898. After that, they ruled it with Egypt. But in reality, it was like a British colony. However, some Mahdist groups continued fighting in Darfur until 1909.

Contents

The Rise of the Mahdist State

Sudan Before the Mahdi

From the early 1800s, Egypt started to conquer Sudan. It became a colony of Egypt. This time was known locally as the Turkiyya, or "Turkish" rule. The Egyptians never fully controlled the region. Their rule and high taxes made them very unpopular.

As people in Sudan grew unhappy, Egypt itself faced problems. This was due to economic and political changes. European powers, especially the British Empire, became involved. In 1869, the Suez Canal opened. It quickly became very important for Britain's trade with India. To protect this waterway, Britain wanted more influence in Egypt.

In 1873, Britain helped set up a system. An Anglo-French group took charge of Egypt's money. This group eventually forced the Egyptian ruler, Khedive Ismail, to step down. His son, Tawfiq, took his place.

After Ismail was removed in 1877, Charles George Gordon resigned. He had been the governor general of Sudan. His replacements struggled to lead. They feared the political chaos in Egypt. Because of this, they failed to continue Gordon's policies. The illegal slave trade grew again. The Sudanese army lacked resources. Unemployed soldiers caused problems in towns. Tax collectors unfairly raised taxes.

Muhammad Ahmad's Leadership

In this difficult time, Muhammad Ahmad ibn as Sayyid Abd Allah appeared. He was a charismatic leader with a religious and political goal. He wanted to remove the Turks and restore Islam to its original purity. Muhammad Ahmad was the son of a boat builder from Dongola. He became a follower of Muhammad ash Sharif, a religious leader. Later, Muhammad Ahmad became a leader himself. He spent years living alone and gained a reputation as a wise teacher.

In 1881, Muhammad Ahmad announced he was the Mahdi. The Mahdi is an "expected one" in Islam. Some of his followers believed he was directly guided by God. He wanted Muslims to follow the Quran and hadith (sayings of Muhammad). He aimed to create a fair society. He said that poverty was good. He spoke out against worldly wealth and luxury. For Muhammad Ahmad, Egypt showed how wealth could lead to bad behavior.

Muhammad Ahmad called for an uprising. His message was very popular among poor communities along the Nile. It combined a nationalist, anti-Egyptian idea with strong religious beliefs.

Even after the Mahdi declared a jihad, the government in Khartoum ignored him. They saw him as just a religious extremist. But the Egyptian government paid more attention when he started criticizing tax collectors. To avoid arrest, the Mahdi and his followers, the Ansar, marched to Kurdufan. There, he gained many new followers, especially from the Baggara people.

From his safe place, he sent messages to religious leaders. He gained their support or their promise to stay neutral. Only the pro-Egyptian Khatmiyyah group did not support him. Merchants and Arab tribes who relied on the slave trade also joined him. The Hadendoa Beja tribe also joined, led by an Ansar captain, Osman Digna.

Mahdist Victories

In early 1882, the Ansar attacked an Egyptian army. This army had 7,000 men and was led by the British. The Ansar, armed with spears and swords, defeated them near Al Ubayyid. They took the Egyptians' rifles, cannons, and ammunition. The Mahdi then surrounded Al Ubayyid. After four months, the city surrendered due to starvation. The Ansar army, now 30,000 strong, then defeated another Egyptian army of 8,000 men at Sheikan.

In the west, the Mahdist uprising gained strength from existing rebel groups. The Turkish rule in Darfur was disliked by locals. Many rebels had already started revolts. Baggara rebels, led by Rizeigat chief Madibo, joined the Mahdi. They surrounded Darfur's Governor-General, Rudolf Carl von Slatin, at Dara. Slatin was captured in 1883. More Darfuri tribes then joined the revolutionaries. Mahdist forces soon controlled most of Darfur. At first, this change was very popular in Darfur.

The Ansar's advance and the Hadendowa uprising in the east created problems. They threatened to cut off communication with Egypt. They also threatened Egyptian army bases in Khartoum, Kassala, Sennar, and Suakin. To avoid a costly war, the British government ordered Egypt to leave Sudan. Gordon, who was again governor general, was tasked with helping Egyptian troops and foreigners leave Sudan.

Abdallahi ibn Muhammad Takes Control

Six months after Khartoum was captured, the Mahdi died. This was likely from typhus (June 22, 1885). The job of setting up a government fell to his deputies. These were three caliphs chosen by the Mahdi. They were chosen to be like the deputies of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. There was rivalry among the three leaders. Each was supported by people from his home region. This continued until 1891. Then, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, with help from the Baqqara Arabs, overcame the others. He became the undisputed leader of the Mahdiyah. Abdallahi, called the Khalifa (successor), removed members of the Mahdi's family and many early followers.

At first, the Mahdiyah was like a military camp. It was run as a jihad state. Sharia courts enforced Islamic law and the Mahdi's rules. These rules had the power of law. After gaining full power, the Khalifa set up a government. He appointed Ansar, usually Baqqara, as leaders over each province. The Khalifa also ruled over the rich Al Jazirah region. He couldn't fully restore its trade. But the Khalifa organized workshops to make ammunition and repair river steamboats.

Relations with neighboring countries were often tense. This was because the Khalifa wanted to spread his version of Islam everywhere. For example, the Khalifa refused an offer from Emperor Yohannes IV of Ethiopia to form an alliance against Europeans. In 1887, a 60,000-man Ansar army invaded Ethiopia. They reached Gondar and took prisoners and goods. The Khalifa then refused to make peace with Ethiopia. In March 1889, an Ethiopian army, led by the emperor, marched on Metemma. However, Yohannes died in the Battle of Gallabat. The Ethiopians then pulled back. Overall, the war with Ethiopia wasted Mahdist resources.

Abd ar Rahman an Nujumi, the Khalifa's best general, invaded Egypt in 1889. But British-led Egyptian troops defeated the Ansar at Tushkah. This defeat ended the idea that the Ansar could not be beaten. The Belgians stopped the Mahdi's men from conquering Equatoria. In 1893, the Italians pushed back an Ansar attack at Akordat (in Eritrea). They forced the Ansar to leave Ethiopia.

As the Mahdist government became more stable, it started collecting taxes. It also put its policies into action across its lands. This made it less popular in many parts of Sudan. Many locals had joined the Mahdists to gain freedom. They wanted to get rid of a strict central government. In Darfur, people rebelled against Abdallahi ibn Muhammad's rule. He was ordering Darfurians to move north to better defend the Mahdist State. He also favored the Baggara people over other groups in Darfur for government jobs. The main resistance was led by Abu Jimeiza of the Tama tribe. The Mahdist government's arrogance also fueled the opposition. Neighboring states began helping the Darfurian rebels. Facing more and more rebels, Mahdist rule in Darfur slowly fell apart. The Mahdist era became known as the umkowakia in Darfur. This means "period of chaos and anarchy."

The End of the Mahdist State

British Reconquest of Sudan

In 1892, Herbert Kitchener became the commander of the Egyptian army. He began preparing to reconquer Sudan. The British felt they needed to take over Sudan because of international events. By the early 1890s, British, French, and Belgian claims met at the source of the Nile River. Britain worried that other colonial powers would use Sudan's instability to take land that used to belong to Egypt. Also, Britain wanted to control the Nile. This was to protect a planned dam at Aswan.

In 1895, the British government allowed Kitchener to start his campaign. Britain provided soldiers and supplies. Egypt paid for the mission. The Anglo-Egyptian Nile Expeditionary Force had 25,800 men. About 8,600 of them were British. The rest were Egyptian soldiers, including six groups recruited in southern Sudan. An armed river fleet supported the force. They also had artillery.

To prepare, the British set up army headquarters at Wadi Halfa. They also strengthened defenses around Sawakin. In March 1896, the campaign began. Kitchener rebuilt a railway south along the Nile. By September, he captured Dongola, the former capital of Nubia. The next year, the British built a new railway directly across the desert. It went from Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamad. They captured Abu Hamad in the Battle of Abu Hamed on August 7, 1897. Anglo-Egyptian units fought hard at Abu Hamad. But there was little other strong resistance until Kitchener reached Atbarah. There, he defeated the Ansar. After this battle, Kitchener's soldiers marched and sailed toward Omdurman. This is where the Khalifa made his final stand.

On September 2, 1898, the Khalifa sent his 52,000-man army to attack the Anglo-Egyptian force. This force was gathered on the plain outside Omdurman. The outcome was clear from the start. This was mainly because of the British's much better weapons. During the five-hour battle, about 11,000 Mahdists died. Anglo-Egyptian losses were 48 dead and fewer than 400 wounded.

Cleaning up the remaining resistance took several years. But organized fighting ended when the Khalifa died. He had escaped to Kordufan. He died in fighting at Umm Diwaykarat in November 1899. The Khalifa had kept a lot of support until his death. But many areas welcomed the end of his rule. Sudan's economy was almost completely destroyed during his time. The population had dropped by about half. This was due to famine, disease, persecution, and war. Millions had died in Sudan from the start of the Mahdist State until its fall. Also, none of the country's old ways or loyalties remained. Tribes had been divided over Mahdism. Religious groups were weakened. Traditional religious leaders had disappeared.

Remaining Resistance

Even though the Mahdist State officially ended after Umm Diwaykarat, some Mahdist groups continued to fight. One officer, Osman Digna, resisted the Anglo-Egyptian forces until he was captured in January 1900. However, the longest-lasting Mahdist resistance was in Darfur. This was despite the fact that Mahdist rule had already been falling apart there. These holdouts were in Kabkabiya (led by Sanin Husain), Dar Taaisha (led by Arabi Dafalla), and Dar Masalit (led by Sultan Abuker Ismail). The newly re-established Sultanate of Darfur had to fight these Mahdist loyalists in a series of long wars. The Kabkabiya holdout under Sanin Husain lasted until 1909. It was finally defeated by the Sultanate of Darfur after a siege of 17 or 18 months.

Life in the Mahdist State

The Mahdist State, also called the Mahdiyah, put in place traditional Sharia Islamic laws. The government was first properly organized under Khalifa Abdallahi ibn Muhammad. He tried to use Islamic law to unite the different peoples of Sudan.

Sudan's new ruler also ordered the burning of family records and law books. This was because they were linked to the old ways. He also believed they made tribalism stronger instead of religious unity.

The Mahdiyah is known as the first true Sudanese nationalist government. The Mahdi said his movement was not just a religious group. He said it was a universal system. He challenged people to join or be destroyed. The Mahdi changed Islam's five pillars. He said that loyalty to him was key to true belief. The Mahdi also added a phrase to the creed, the shahada. It said, "and Muhammad Ahmad is the Mahdi of God and the representative of His Prophet." Also, serving in the jihad replaced the hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca. This became a duty for believers. Zakat (giving to charity) became the tax paid to the state. The Mahdi said these changes were based on instructions he received from God in visions.

The Mahdist government was also known for its harsh treatment of Christians in Sudan, including Copts.

Military Strength

The Mahdist Army

The Mahdist State had a large army. It became more professional over time. Early on, Mahdist armies recruited soldiers who left the Egyptian Army. They also organized professional soldiers called the jihadiya. These were mostly Black Sudanese. Tribal spearmen, swordsmen, and cavalry supported them. The jihadiya and some tribal units lived in military camps. Others were more like local militias.

The Mahdist armies also had some artillery. This included mountain guns and even machine guns. However, these were few. They were only used to defend important towns and on river steamboats. The Mahdist soldiers were very motivated by their beliefs. Mahdist commanders used their riflemen to cover charges by their infantry and cavalry. These attacks were often effective. But they also led to very high losses when used without careful planning. Europeans often called the Mahdist soldiers "dervishes."

Muhammad Ahmad's early rebel force was mostly poor Arab communities along the Nile. Later Mahdiyah armies recruited from many groups. This included mostly independent groups like the Beja people. The Mahdi's early forces were called "ansar." They were divided into three units, each led by a Khalifa. These units were called raya ("flags") after their banners. The "Black Flag" was mostly from western Sudan, mainly Baggara. It was led by Abdallahi ibn Muhammad. The "Red Flag" was led by Muhammad al-Sharif. It mostly had recruits from northern river areas. The "Green Flag" under Ali Hilu included troops from southern tribes. These tribes lived between the White and Blue Nile.

After the Mahdi's death, the "Black Flag" command went to Abdallahi ibn Muhammad's brother, Yaqub. It became the state's main army, based in Omdurman. As the Mahdist State grew, local commanders raised new armies. These had their own flags and were modeled after the main armies. The most elite forces were the Mulazimiyya. These were Abdallahi ibn Muhammad's bodyguards. They were led by Uthman Shaykh al-Din. They were based at the capital and had 10,000 men, most armed with rifles.

The "flags" were further divided into rubs ("quarters"). Each rub had 800 to 1200 fighters. In turn, rubs were split into four sections. One was for administration. One was jihadiya. One was for infantry using swords and spears. And one was for cavalry. The jihadiya units were further split into "standards" of 100 men. These were led by officers called ra's mi'a. They were also split into muqaddamiyya of 25 men under a muqaddam.

The Mahdist navy started during the early rebellion. Rebels took control of boats on the Nile River. In May 1884, the Mahdists captured the steamboats Fasher and Musselemieh. Later, they took the Muhammed Ali and Ismailiah. Also, several armed steamboats meant to help Charles Gordon were wrecked in 1885. At least two of these, the Bordein and Safia, were saved by the Mahdists. The captured steamboats had light cannons. Egyptians and Sudanese crewed them. The Mahdist navy also used supply ships.

In October 1898, parts of the Mahdist navy went up the White Nile. They were to help an expedition against Emin Pasha's forces. The Ismailiah sank on August 17, 1898. It was placing naval mines on the Nile near Omdurman. These mines were to block British gunboats. One mine exploded by accident, destroying the ship. The Safia and Tawfiqiyeh, towing barges with 2,000 to 3,000 soldiers, went up the Blue Nile. They were sent against French forces at Fashoda on August 25, 1898. There, the two ships attacked the fort. But the Safia broke down. It was under heavy fire before the Tawfiqiyeh towed it to safety. The Tawfiqiyeh then went back to Omdurman. But it met a large Anglo-Egyptian fleet and surrendered.

The Mahdist navy fought its last battle on September 11 or 15, 1898. The Anglo-Egyptian gunboat Sultan met the Safia near Reng. The two ships fought a short battle. The Safia was badly damaged before being captured. The Bordein was eventually captured when Omdurman fell to the Anglo-Egyptian forces.

Military Uniforms

At the start of his uprising, the Mahdi told his followers to wear similar clothes. This was the jibba. So, the Mahdi's and Abdallahi ibn Muhammad's main army looked somewhat uniform early on. In contrast, other allied armies did not wear the jibba at first. They kept their traditional clothes. Riverine forces from the Ja'alin tribe and the Danagla mostly wore simple white robes (tobe). The Beja also did not wear the jibba until 1885.

As time passed, the Mahdist State became better organized. Under Khalifa Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, its armies became more professional. By the 1890s, factories in Omdurman made many jibba. This was to provide clothes for the troops. The jibba still varied in style. Some tribes and armies preferred certain patterns and colors. But the Mahdist forces looked more and more professional. The jibba also showed a fighter's rank. Lower-ranking commanders (emirs) wore more colorful jibba. The most senior military leaders preferred simple designs. This showed their religious devotion. The Khalifa wore plain white. Some Mahdist troops had mail armor, helmets, and quilted coats. But these were more often used in parades than in battle. One unit, the Mulazimiyya, had a full uniform. All its members wore identical white-red-blue jibba.

Flags of the Mahdist State

The Mahdist State and its armies did not have one single flag design. But they used certain designs many times. Most flags had four lines of Arabic text. These showed loyalty to God, Muhammad, and the Mahdi. The flags were usually white with colored borders. The text was in different colors. Most military units had their own flags.

See Also

- History of Sudan

- Mahdist War

- In Desert and Wilderness (novel)

- Millennarianism in colonial societies