History of Sudan facts for kids

The history of Sudan tells the story of the land that is now the Republic of the Sudan and also what became South Sudan in 2011. This area is part of a larger African region called "Sudan". The name comes from an Arabic phrase meaning "land of the black people". It sometimes refers to the wide Sahel area in West and Central Africa.

Modern Sudan was formed in 1956. Its borders came from the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, which started in 1899. Before 1899, "Sudan" often meant the lands ruled by the Turks and the Mahdists. This area was a changing territory between Egypt in the north and regions near modern Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia in the south.

The early history of the Kingdom of Kush in northern Sudan is linked to ancient Egypt. They were often allies. Because it was close to Egypt, Sudan was part of the wider history of the Near East. The important 25th dynasty of Egypt came from Kush. Later, three Nubian kingdoms – Nobatia, Makuria, and Alodia – became Christian in the 500s. The Old Nubian language is the oldest recorded Nilo-Saharan language. Its first writings date back to the 700s, using a form of the Coptic alphabet.

While Islam was present on Sudan's Red Sea coast since the 600s, the Nile Valley did not become mostly Muslim until the 1300s and 1400s. This happened after the Christian kingdoms declined. The Sultanate of Sennar took over much of the Nile Valley in the early 1500s. The kingdoms of Darfur ruled western Sudan. Two smaller kingdoms, Shilluk Kingdom and Taqali, arose in the south. But in the 1820s, Muhammad Ali of Egypt took control of both northern and southern regions. His harsh rule led to anger against the Egyptian and British rulers. This anger helped create the Mahdist State, started by Muhammad Ahmad in 1881.

Since gaining independence in 1956, Sudan has faced many internal conflicts. These include the First Sudanese Civil War (1955–1972), the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005), and the War in Darfur (2003–2010). These conflicts led to South Sudan becoming an independent country on July 9, 2011. After that, another civil war happened in South Sudan (2013-2020).

Contents

Ancient History of Sudan

Early People in the Nile Valley

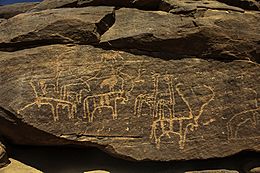

Around 8,000 BCE, people in the Nile Valley started living in one place. They built villages with strong mud-brick houses. They hunted and fished in the Nile. They also gathered grain and herded cattle. By 5,000 BCE, people from the drying Sahara desert moved into the Nile Valley. They brought farming with them. Over time, this mix of people developed a social system. By 1700 BCE, they formed the Kingdom of Kush, with its capital at Kerma.

Ancient research shows that people in Lower Nubia and Upper Egypt were very similar in culture and background before the time of the pharaohs. They both developed systems of kingship around 3300 BCE. Sudan, along with other countries on the Red Sea, is thought to be the ancient land of Punt. The ancient Egyptians called it "God's Plan." It was first mentioned around 1000 BCE.

Early Groups in Eastern Sudan

In eastern Sudan, the Butana Group appeared around 4000 BC. These people made simple decorated pots. They lived in round huts. They were likely herders and hunters. They also ate land snails, and there is some proof of farming.

The Gash Group started around 3000 BC. They are known from several sites. These people made decorated pottery and lived by farming and raising cattle. Mahal Teglinos was a large and important place. Mud brick houses were found there. Seals and seal marks show that they had a good system of managing things. Important burials were marked with rough tombstones. In the second millennium BC, the Jebel Mokram Group followed. They made pottery with simple designs. They lived in simple round huts. Raising cattle was probably their main way of life.

Ancient Kingdoms and Empires

The Kingdom of Kush

The earliest records of northern Sudan come from ancient Egypt. They called the land upstream Kush. For over 2,000 years after the Old Kingdom (around 2700–2180 BC), Egypt had a strong influence on its southern neighbor. Even later, Egyptian culture and religion remained important.

Over time, trade grew between them. Egyptian traders carried grain to Kush. They returned to Aswan with ivory, incense, animal hides, and carnelian stone. Carnelian was valued for jewelry and arrowheads. Egyptians especially liked the gold from Nubia and soldiers from Kush for the pharaoh's army. Egyptian armies sometimes went into Kush during the Old Kingdom. But they did not try to stay there permanently until the Middle Kingdom (around 2100–1720 BC). Then, Egypt built many forts along the Nile. These forts went as far south as Samnah to protect the flow of gold from mines.

Around 1720 BC, people called the Hyksos took over Egypt. They ended the Middle Kingdom and cut ties with Kush. They also destroyed the forts along the Nile. After Egypt left, a unique Kushite kingdom grew at al-Karmah, near modern Dongola. When Egypt's power returned during the New Kingdom (around 1570–1100 BC), the pharaoh Ahmose I made Kush an Egyptian province. It was ruled by a viceroy. Even though Egypt's direct control reached only to the Fourth Cataract, Egyptian records show that tribute came from areas reaching the Red Sea and upstream to where the Blue Nile and White Nile rivers meet. Egyptian rulers made sure local chiefs were loyal by having their children serve at the pharaoh's court. Egypt also expected gold and workers from Kushite chiefs.

Once Egypt controlled Kush, Egyptian officials, priests, traders, and artists settled there. The Egyptian language became widely used. Many rich Kushites worshipped Egyptian gods and built temples for them. These temples were important religious centers until Christianity came to the region in the 500s. When Egyptian power weakened, the Kushite leaders saw themselves as guardians of Egyptian culture and religion.

By the 1000s BC, the power of the New Kingdom pharaohs had lessened. Egypt was divided, and Egyptian control of Kush ended. For 300 years after the Egyptians left, there are no written records from Kush. However, in the early 700s BC, Kush became an independent kingdom. It was ruled from Napata by strong kings who slowly expanded into Egypt. Around 750 BC, a Kushite king named Kashta conquered Upper Egypt. His successor, Piye, took control of the Nile Delta and conquered all of Egypt. This started the Twenty-fifth Dynasty. Piye began a line of kings who ruled Kush and Thebes for about 100 years.

This dynasty's actions in the Near East led to a conflict with Assyria. Assyria was a powerful state that controlled a large empire. Taharqa (688–663 BC), the last Kushite pharaoh, was defeated by Sennacherib of Assyria. Sennacherib's successor, Esarhaddon, invaded Egypt in 674 BC. He defeated Taharqa and quickly conquered the land. Taharqa fled back to Nubia. Assyria put Egyptian princes in charge as their rulers. However, Taharqa returned later and took back part of Egypt. Esarhaddon died while preparing to go back to Egypt to fight the Kushites again.

Esarhaddon's successor, Ashurbanipal, sent an army that again defeated Taharqa and drove him out of Egypt. Taharqa died in Nubia two years later. His successor, Tantamani, tried to get Egypt back. He defeated Necho I, who was put in power by Ashurbanipal. Tantamani took Thebes. Then, the Assyrians sent a powerful army south. Tantamani was badly defeated, and the Assyrian army destroyed Thebes so much that it never fully recovered. An Egyptian ruler, Psamtik I, was placed on the throne by Ashurbanipal. This ended the Kushite Empire.

The Kingdom of Meroë

Egypt's next rulers could not fully control Kush again. Around 590 BC, an Egyptian army attacked Napata. This forced the Kushite rulers to move their capital further south to Meroë, near the Sixth Cataract. For several centuries, the Meroitic kingdom grew on its own. It was not controlled by Egypt, which later came under Iranian, Greek, and Roman rule.

At its strongest in the 200s and 100s BC, Meroë stretched from the Third Cataract in the north to Soba, near modern Khartoum, in the south. Meroë had a line of rulers who followed Egyptian traditions. They built stelae (stone slabs) to record their achievements. They also built Nubian pyramids for their tombs. These structures, along with the ruins of palaces and temples at Meroë, show a strong government. This government used skilled artisans and a large workforce. A good irrigation system allowed more people to live there than in later times. By the 100s BC, the use of Egyptian hieroglyphs changed to a Meroitic alphabet. This alphabet was for the Nubian-related language spoken by the people.

Meroë's system for choosing a new ruler was not always based on who was next in line. The most worthy member of the matrilineal royal family often became king. The kandake, or queen mother, was very important in choosing the next ruler. The crown seemed to pass from brother to brother (or sister). Only when there were no more siblings did it pass from father to son.

While Napata remained Meroë's religious center, northern Kush eventually faced problems. It was pressured by the Blemmyes, who were nomads from east of the Nile. However, the Nile still connected the region to the Mediterranean world. Meroë also traded with Arab and Indian merchants along the Red Sea coast. It adopted Greek and Indian cultural ideas into its daily life. There is some evidence that metalworking skills might have spread from Meroë's iron factories across Africa to West Africa.

Relations between Meroë and Egypt were not always peaceful. In response to Meroë's attacks into Upper Egypt, a Roman army moved south and destroyed Napata in 23 BC. However, the Roman commander quickly left the area. He thought it was too poor to be worth taking over.

In the 100s AD, the Nobatia lived on the west bank of the Nile in northern Kush. They were likely one of several groups of armed warriors who rode horses and camels. They offered their fighting skills to Meroë for protection. Eventually, they married into the Meroitic people and became a military ruling class. Until almost the 400s, Rome paid the Nobatia. Rome used Meroë as a barrier between Egypt and the Blemmyes.

Meanwhile, the old Meroitic kingdom became smaller. This was because the powerful Kingdom of Aksum in the east was growing. By 350 AD, King Ezana of Axum had captured and destroyed the capital of Meroë. This ended the kingdom's independent existence and took over its land.

Medieval Nubia (Around 350–1500 AD)

Around 400 AD, the Blemmyes created a short-lived state in Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia. But before 450 AD, the Nobatians drove them out of the Nile Valley. The Nobatians then formed their own kingdom, Nobatia. By the 500s, there were three Nubian kingdoms: Nobatia in the north, with its capital at Pachoras (Faras); the central kingdom, Makuria, centered at Tungul (Old Dongola); and Alodia, in the heart of the old Kushite kingdom, with its capital at Soba (now near modern Khartoum). All three converted to Christianity in the 500s. In the 600s, Nobatia became part of Makuria.

Between 639 and 641 AD, the Muslim Arabs of the Rashidun Caliphate conquered Byzantine Egypt. In 641 or 642, and again in 652, they invaded Nubia. But the Nubians fought them off. This made the Nubians one of the few who defeated the Arabs during the Islamic expansion. After this, the Makurian king and the Arabs agreed to a special peace treaty. It included an annual exchange of gifts, recognizing Makuria's independence. While the Arabs did not conquer Nubia, they started to settle east of the Nile. There, they founded port towns and married into the local Beja people.

From the mid-700s to the mid-1000s, Christian Nubia had its Golden Age. Its political power and culture were at their peak. In 747, Makuria invaded Egypt. It did so again in the early 960s, reaching as far north as Akhmim. Makuria had close family ties with Alodia. This might have led to the two kingdoms joining for a time. The culture of Medieval Nubians is called "Afro-Byzantine." The "African" part became more important over time. Arab influence also grew. The government was very organized, based on the Byzantine system of the 500s and 600s. Arts thrived, especially pottery and wall paintings. The Nubians created their own alphabet for their language, Old Nobiin. It was based on the Coptic alphabet, and they also used Greek, Coptic, and Arabic. Women had a high social status. They could get an education, own land, and often used their wealth to support churches and art. Even the royal succession was matrilineal. The son of the king's sister was the rightful heir.

From the late 1000s or 1100s, Makuria's capital, Dongola, began to decline. Alodia's capital also declined in the 1100s. In the 1300s and 1400s, Bedouin tribes took over most of Sudan. They moved into the Butana, the Gezira, Kordofan, and Darfur. In 1365, a civil war forced the Makurian court to flee to Gebel Adda. Dongola was destroyed and left to the Arabs. After this, Makuria continued as a small kingdom.

The last known Makurian king was Joel, who ruled in 1463 and 1484. Under him, Makuria might have had a short period of rebirth. After his death, the kingdom likely fell apart. To the south, the kingdom of Alodia fell to either the Arabs or the Funj, an African people from the south. This happened sometime between the late 1400s and early 1500s. A small part of Alodia might have survived as the kingdom of Fazughli until 1685.

Islamic Kingdoms (Around 1500–1821)

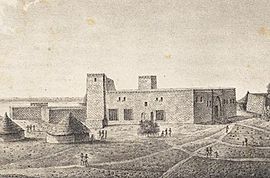

In 1504, the Funj people founded the kingdom of Sennar. The land ruled by Abdallah Jamma became part of it. By 1523, when Jewish traveler David Reubeni visited Sudan, the Funj state already reached as far north as Dongola. Meanwhile, Sufi holy men began teaching Islam along the Nile. They settled there in the 1400s and 1500s. By David Reubeni's visit, King Amara Dunqas, who was previously a Pagan or Christian, was recorded as Muslim. However, the Funj kept some non-Islamic customs, like divine kingship and drinking alcohol, until the 1700s. Sudanese folk Islam kept many rituals from Christian traditions until recently.

Soon, the Funj clashed with the Ottomans. The Ottomans had taken Suakin around 1526. They pushed south along the Nile, reaching the third Nile cataract area in 1583-1584. The Funj stopped an Ottoman attempt to capture Dongola in 1585. After that, Hannik, just south of the third cataract, became the border between the two states. After the Ottoman invasion, Ajib, a minor king of northern Nubia, tried to take power. The Funj killed him in 1611-1612. But his successors, the Abdallab, were given the power to rule everything north of where the Blue and White Niles meet, with much freedom.

During the 1600s, the Funj state was at its largest. But in the next century, it began to decline. A change in rulers happened in 1718. Another change in 1761-1762 led to the Hamaj Regency. The Hamaj people, from the Ethiopian borderlands, truly ruled, while the Funj sultans were just puppets. Soon after, the sultanate began to break apart. By the early 1800s, it was mostly limited to the Gezira region.

The change in rulers in 1718 led to a focus on more traditional Islam. This also helped the Arabization of the state. To make their rule over their Arab subjects seem right, the Funj claimed to be descended from the Umayyad family. North of where the Blue and White Niles meet, as far as Al Dabbah, the Nubians adopted the tribal identity of the Arab Jaalin. By the 1800s, Arabic had become the main language of central Sudan along the river and most of Kordofan.

West of the Nile, in Darfur, the Islamic period first saw the rise of the Tunjur kingdom. It replaced the old Daju kingdom in the 1400s and reached as far west as Wadai. The Tunjur people were probably Arabized Berbers. Their rulers, at least, were Muslims. In the 1600s, the Fur Keira sultanate took power from the Tunjur. The Keira state, which was Muslim since the time of Sulayman Solong (ruled around 1660–1680), was first a small kingdom. But it grew westward and northward in the early 1700s. Under Muhammad Tayrab (ruled 1751–1786), it expanded eastward, conquering Kordofan in 1785. This empire, which was roughly the size of modern Nigeria, was at its peak until 1821.

Sudan in the 1800s

Egyptian Takeover

From 1805, Egypt quickly modernized under Muhammad Ali Pasha. He declared himself the Khedive, challenging the Ottoman Sultan. In a few decades, Muhammad Ali turned Egypt from a forgotten Ottoman area into a nearly independent state. He wanted to expand Egypt's borders south into Sudan. This was to make Egypt safer and to get Sudan's natural resources. Between 1820 and 1821, Egyptian forces led by Muhammad Ali's son conquered northern Sudan. Because Egypt was still officially part of the Ottoman Empire, the Egyptian rule was called the Turkiyah. Historically, the swampy areas of the Sudd made it hard to expand further south. Although Egypt claimed all of present-day Sudan for most of the 1800s, it could not fully control the entire area. In the later years of the Turkiyah, British missionaries came from modern Kenya to southern Sudan to convert local tribes to Christianity.

The Mahdist State and Joint Rule

In 1881, a religious leader named Muhammad Ahmad said he was the Mahdi ("guided one"). He started a war to unite the tribes in western and central Sudan. His followers were called "Ansars" ("followers"). They still use this name today and are linked to the largest political group, the Umma Party. Taking advantage of the problems caused by Ottoman-Egyptian rule, the Mahdi led a revolt. It ended with the fall of Khartoum on January 26, 1885. The British governor-general of Sudan, Major-General Charles George Gordon, and many people in Khartoum were killed.

The Mahdi died in June 1885. He was followed by Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, known as the Khalifa. The Khalifa expanded Sudan's area into Ethiopia. After his wins in eastern Ethiopia, he sent an army to invade Egypt. But the British defeated it at Toshky. The British then realized how weak Sudan was.

An Anglo-Egyptian force led by Lord Kitchener was sent to Sudan in 1898. Sudan was declared a condominium in 1899. This meant it was ruled jointly by Britain and Egypt. The Governor-General of Sudan was appointed by "Khedival Decree," not just by the British Crown. But while it looked like joint rule, the British Empire made most of the decisions and provided most of the top leaders.

British Control (1896–1955)

In 1896, a Belgian group claimed parts of southern Sudan. This area became known as the Lado Enclave. It was officially part of the Belgian Congo. An agreement in 1896 between the United Kingdom and Belgium stated that the enclave would go to the British after King Leopold II died in December 1909.

At the same time, the French claimed several areas: Bahr el Ghazal and the Western Upper Nile up to Fashoda. By 1896, they had strong control over these areas. They planned to add them to French West Africa. A conflict known as the Fashoda incident happened between France and the United Kingdom over these areas. In 1899, France agreed to give the area to the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.

From 1898, the United Kingdom and Egypt ruled all of present-day Sudan as the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. But northern and southern Sudan were managed as separate areas. In the early 1920s, the British passed laws that required passports to travel between the two zones. Permits were also needed to do business from one zone to the other. There were completely separate administrations.

In the south, English, Dinka, Bari, Nuer, Latuko, Shilluk, Azande, and Pari (Lafon) were official languages. In the north, Arabic and English were used. The British discouraged Islam in the south. Christian missionaries were allowed to work there. British governors of south Sudan attended colonial meetings in East Africa, not in Khartoum. The British hoped to add south Sudan to their East African colonies.

Most of the British effort was on developing the economy and services in the north. Southern political arrangements stayed largely as they were before the British arrived. Until the 1920s, the British had limited power in the south.

To establish their power in the north, the British supported Sayyid Ali al-Mirghani, head of the Khatmiyya group, and Sayyid Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi, head of the Ansar group. The Ansar group became the Umma party, and Khatmiyya became the Democratic Unionist Party.

In 1943, the British began preparing the north for self-rule. They set up a North Sudan Advisory Council to give advice on governing the six northern provinces. Then, in 1946, the British changed their plan. They decided to combine north and south Sudan under one government. Southern Sudanese leaders were told at the Juba Conference of 1947 that they would be governed with the north. From 1948, 13 delegates, chosen by the British, represented the south in the Sudan Legislative Assembly.

Many southerners felt let down by the British. They were largely left out of the new government. The language of the new government was Arabic. But most southern Sudanese officials and politicians had been trained in English. Of the 800 new government jobs left by the British in 1953, only four went to southerners.

Also, the political structure in the south was not as organized as in the north. So, southern political groups were not represented at the meetings that created the modern state of Sudan. Because of this, many southerners did not see Sudan as a fair or rightful state.

Independent Sudan (1956 to Today)

Independence and the First Civil War

In February 1953, the United Kingdom and Egypt agreed that Sudan would govern itself and decide its own future. The move towards independence began with the first parliament in 1954. On August 18, 1955, a revolt in the army broke out in Torit, Southern Sudan. Although it was quickly stopped, it led to a small-scale guerrilla war by former southern rebels. This marked the start of the First Sudanese Civil War. On December 15, 1955, Sudan's Premier, Ismail al-Azhari, announced that Sudan would declare independence in four days. On December 19, 1955, the Sudanese parliament declared Sudan's independence. The British and Egyptian governments recognized Sudan's independence on January 1, 1956. The United States was one of the first countries to recognize the new state.

However, the Arab-led government in Khartoum did not keep its promises to southerners to create a federal system. This led to a rebellion by southern army officers, which started 17 years of civil war (1955–1972). Early in the war, hundreds of northern officials, teachers, and others serving in the south were killed.

The National Unionist Party (NUP), led by Prime Minister Ismail al-Azhari, formed the first government. It was soon replaced by a group of conservative political parties. In 1958, after economic problems and political struggles that stopped the government from working, Chief of Staff Major General Ibrahim Abboud took over the government in a peaceful coup d'état (a sudden, illegal takeover of power).

General Abboud did not keep his promises to return Sudan to civilian rule. Public anger against army rule led to riots and strikes in late October 1964. These forced the military to give up power.

A temporary government followed Abboud's rule. Then, parliamentary elections in April 1965 led to a government made of the Umma and National Unionist Parties, led by Prime Minister Muhammad Ahmad Mahjoub. Between 1966 and 1969, Sudan had several governments. They could not agree on a permanent constitution or deal with problems like group conflicts, slow economic growth, and ethnic disagreements. The early governments after independence were mostly led by Arab Muslims. They saw Sudan as a Muslim Arab state. The proposed 1968 constitution was arguably Sudan's first constitution based on Islamic law.

The Nimeiry Years

Dissatisfaction led to a second coup d'état on May 25, 1969. The leader of the coup, Colonel Gaafar Nimeiry, became prime minister. The new government ended parliament and banned all political parties.

Disagreements between different groups within the ruling military government led to a short but successful coup in July 1971. It was led by the Sudanese Communist Party. A few days later, anti-communist military groups put Nimeiry back in power.

In 1972, the Addis Ababa Agreement ended the north-south civil war and gave the south some self-rule. This led to a ten-year break in the civil war.

Until the early 1970s, Sudan mostly grew food for its own people. In 1972, the Sudanese government became more friendly with Western countries. It planned to export food and cash crops. However, prices for goods dropped throughout the 1970s, causing economic problems for Sudan. At the same time, the cost of paying back loans for farming equipment increased. In 1978, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) worked with the government on an economic plan. This plan further promoted large-scale farming for export. This caused big economic problems for the herding communities in Sudan.

In 1976, the Ansars tried a bloody but unsuccessful coup. In July 1977, President Nimeiry met with Ansar leader Sadiq al-Mahdi. This opened the way for peace. Hundreds of political prisoners were released. In August, a general pardon was announced for all who opposed Nimeiry's government.

Military Support

Sudan got its weapons from many countries. After independence, the army was trained and supplied by the British. But relations were cut off after the Arab-Israel Six-Day War in 1967. At this time, relations with the US and West Germany were also cut off. From 1968 to 1971, the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries sold many weapons and provided training to Sudan. During this time, the army grew from 18,000 to about 60,000 soldiers. Many tanks, aircraft, and artillery were bought. They were the main equipment until the late 1980s. Relations with the Soviet Union cooled after the 1971 coup. The Khartoum government then looked for other suppliers. Egypt was the most important military partner in the 1970s, providing missiles and other military gear.

Western countries started supplying Sudan again in the mid-1970s. The United States began selling a lot of equipment around 1976. Military sales reached their highest in 1982 at $101 million. The alliance with the United States grew stronger under President Ronald Reagan. American aid increased from $5 million in 1979 to $200 million in 1983, and then to $254 million in 1985. Most of this was for military programs. Sudan became the second-largest receiver of US aid in Africa, after Egypt. It was decided to build four air bases and a powerful listening station for the CIA near Port Sudan.

Second Civil War and Darfur Conflict

In 1983, the civil war in the South started again. This was because the government tried to make Sudan more Islamic. It wanted to use Islamic law, among other things. After several years of fighting, the government made a deal with southern groups. In 1984 and 1985, after a period of drought, millions of people faced hunger, especially in western Sudan. The government tried to hide this situation from the world.

In March 1985, the government announced higher prices for basic goods. This was asked for by the IMF. This caused the first protests. On April 2, eight unions called for action and a "general strike until the current government is gone." On April 3, huge protests happened in Khartoum and other main cities. The strike stopped government and economic activities. On April 6, 1985, a group of military officers, led by Lieutenant General Abd ar Rahman Siwar adh Dhahab, overthrew Nimeiri. Nimeiri fled to Egypt. Three days later, Dhahab allowed the creation of a 15-person Transitional Military Council (TMC) to rule Sudan.

In June 1986, Sadiq al Mahdi formed a government with the Umma Party, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), the National Islamic Front (NIF), and four southern parties. However, Sadiq was a weak leader and could not govern Sudan well. His government was marked by party conflicts, corruption, personal rivalries, and political instability. After less than a year, Sadiq al Mahdi dismissed the government. It had failed to write new laws, agree with the IMF, end the civil war in the south, or attract money from Sudanese living abroad. To keep the support of the DUP and southern parties, Sadiq formed another ineffective government.

In 1989, the government and southern rebels began to talk about ending the war. But a military group took power in a coup. This group was not interested in making compromises. The leader of this group, Omar al-Bashir, gained more power over the next few years and declared himself president.

The civil war forced over 4 million southerners to leave their homes. Some went to southern cities like Juba. Others traveled north to Khartoum or even to Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Egypt, and other nearby countries. These people could not grow food or earn money, so hunger and starvation became common. The lack of investment in the south also led to what aid groups call a "lost generation." These young people lacked education, basic health care, and good job opportunities in the small economies of the south or north.

In early 2003, a new rebellion started in the western region of Darfur. It was led by the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) and Justice and Equality Movement (JEM). The rebels said the government was ignoring the Darfur region. Both the government and the rebels were accused of terrible acts in this war. Most of the blame fell on Arab groups (Janjaweed) allied with the government. The rebels claimed these groups were trying to remove certain ethnic groups from Darfur. The fighting forced hundreds of thousands of people to leave their homes. Many sought safety in nearby Chad. Estimates of the number of deaths vary widely, from under 20,000 to several hundred thousand, from fighting or from hunger and disease caused by the conflict.

In 2004, Chad helped with talks in N'Djamena. This led to the April 8 Humanitarian Ceasefire Agreement between the Sudanese government, the JEM, and the SLA. However, the conflict continued despite the ceasefire. The African Union (AU) formed a group to watch the ceasefire. In August 2004, the African Union sent 150 Rwandan troops to protect the ceasefire monitors. But it soon became clear that 150 troops were not enough. So, 150 Nigerian troops joined them.

On September 18, 2004, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1564. It stated that the government of Sudan had not kept its promises. It expressed worry about helicopter attacks and attacks by the Janjaweed militia on villages in Darfur. It welcomed the African Union's plan to increase its monitoring mission in Darfur and urged all countries to support these efforts. During 2005, the African Union Mission in Sudan force grew to about 7,000 troops.

The Chadian-Sudanese conflict officially began on December 23, 2004. The government of Chad declared a state of war with Sudan. It called on its citizens to fight against Chadian rebels (supported by Sudan) and Sudanese militias. These groups attacked villages in eastern Chad, stealing cattle, killing people, and burning houses.

Peace talks between the southern rebels and the government made good progress in 2003 and early 2004. A final peace treaty was signed on January 9, 2005, in Nairobi. The main points of the peace treaty were:

- The south would have self-rule for six years. After that, people in southern Sudan would vote on whether to become independent.

- Both sides would combine their armed forces into a 39,000-strong force after six years, if the vote for independence failed.

- Money from oil fields would be shared equally between the north and south.

- Government jobs would be split in different ways.

- Islamic law would remain in the north. The elected assembly in the south would decide if Islamic law would continue there.

Islamic Laws and Practices

The 1990s saw a push to enforce strict Islamic laws and practices under the National Islamic Front and Hasan al-Turabi. Education changed to focus on Arab and Islamic culture. For example, students memorized the Quran in religious schools. School uniforms were replaced with military clothes, and students did military drills. Religious police made sure women wore veils, especially in government offices and universities. The political atmosphere became much harsher. The war against the non-Muslim south was called a jihad (holy war). On state television, actors pretended to have "weddings" between holy war martyrs and heavenly virgins. Turabi also gave safety and help to non-Sudanese Islamists, including Osama bin Laden and other Al Qaeda members.

Recent History (2006 to 2011)

On August 31, 2006, the United Nations Security Council approved Resolution 1706. This plan was to send a new peacekeeping force of 17,300 people to Darfur. However, for months, the UN force could not go to Darfur. This was because the Government of Sudan strongly opposed a UN-only peacekeeping operation. The UN then tried a different approach. They worked to strengthen the African Union mission first, before transferring authority to a joint African Union/United Nations peacekeeping operation. After long talks and much international pressure, Sudan finally accepted the peacekeeping operation in Darfur.

In 2009, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for al-Bashir. He was accused of serious crimes. In 2009 and 2010, a series of conflicts between rival nomadic tribes in South Kordofan caused many deaths and forced thousands to leave their homes.

An agreement to restore peace between Chad and Sudan was signed on January 15, 2010. This ended a five-year conflict between them. The Sudanese government and the JEM signed a ceasefire agreement, ending the Darfur conflict in February 2010.

In January 2011, a vote on independence for Southern Sudan was held. The South voted strongly to separate later that year and become the Republic of South Sudan. Its capital was Juba, and Kiir Mayardit was its first president. Al-Bashir said he accepted the result. But violence soon broke out in the disputed region of Abyei, which both the North and South claimed.

On June 6, 2011, armed conflict started in South Kordofan between the forces of Northern and Southern Sudan. This happened before the South's planned independence on July 9. This was followed by an agreement for both sides to leave Abyei. On June 20, the parties agreed to remove military forces from the disputed Abyei area. Ethiopian peacekeepers would be sent there. On July 9, 2011, South Sudan became an independent country.

After Omar al-Bashir (2019–Present)

In April 2019, after several months of protests, Sudan's president Omar al-Bashir was removed from power. Since his government fell, the country has been ruled by the Sovereignty Council of Sudan. This council includes both military and civilian representatives. It is the highest power during the transition period. Until the next Sudanese General Elections, planned for 2022, the country is led by the Chairman of the Transitional Sovereign Council, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok.

After al-Bashir was removed, street protests continued. They were organized by the Sudanese Professionals Association and other groups that wanted democracy. They called for the ruling Transitional Military Council (TMC) to step aside for a civilian-led government. They also wanted other changes in Sudan. Talks between the TMC and the civilian groups to form a joint government happened in April and May. But they stopped when the Rapid Support Forces and other TMC security forces killed 128 people in the Khartoum massacre on June 3, 2019.

In October 2020, Sudan made an agreement to normalize relations with Israel. This was part of a deal with the United States to remove Sudan from the U.S. list of countries that support terrorism.

Conflicts with Ethiopia (2020–2021)

During the 2020–2021 Tigray War in Ethiopia, Sudan also became involved. On December 18, 2020, Sudanese military forces were said to be moving towards the disputed border area with Ethiopia. Reports stated that the Sudanese Commander-in-Chief, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, visited the area. Egypt criticized Ethiopia's border attack on Sudan. It said it fully supported Sudan and called for steps to prevent such events from happening again. Sudan accused the Ethiopian government of using artillery against Sudanese troops. Tensions had been rising because Sudan reoccupied land it said was taken by Ethiopian farmers. Ethiopia had not commented on the matter. On December 18, 2020, Sudanese authorities told recently arrived Tigrayan refugees to move to the mainland of Sudan. This was due to fears of a possible war between Ethiopia and Sudan.

On December 19, 2020, tension between Ethiopia and Sudan increased. Sudan sent more troops, including Rapid Support Forces, and equipment to the border area. Support came from the Beni Amer and al-Habb tribes, including food and money. Talks with Ethiopia stopped. A report stated that on December 19, 2020, Sudan had captured Eritrean soldiers. They were dressed in Amhara militia uniforms and fighting alongside Amhara special forces. On December 20, 2020, the Sudanese army regained control of Jabal Abu Tayyur, in the disputed land on the Ethiopia-Sudan border. Heavy fighting broke out between the Sudanese military and the Ethiopian National Defense Forces and Amhara militia near the border.

2021 Military Takeover

On October 25, 2021, the Sudanese military, led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, took control of the government in a military takeover. At least five senior government figures were arrested at first. Civilian Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok refused to support the takeover. On October 25, he called for public resistance. He was placed under house arrest on October 26.

Key civilian groups, including the Sudanese Professionals Association and Forces of Freedom and Change, called for peaceful resistance and refusal to work with the military leaders.

Facing resistance from inside Sudan and from other countries, al-Burhan said he was willing to bring back the Hamdok government on October 28. However, the Prime Minister refused this first offer. He said any further talks depended on fully bringing back the system that was in place before the takeover. On November 21, 2021, Hamdok and al-Burhan signed a deal. It put Hamdok back as prime minister and said all political prisoners would be freed. Civilian groups rejected the deal, refusing to share power with the military.

2023 Fighting

On April 15, 2023, the Rapid Support Forces attacked government positions. As of April 15, 2023, both the RSF and al-Burhan claimed control of most important government sites. Fighting continued.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Sudán para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Sudán para niños

- History of Africa

- History of Egypt

- History of North Africa

- History of South Sudan

- List of governors of pre-independence Sudan

- List of heads of government of Sudan

- List of heads of state of Sudan

- Politics of Sudan

- Khartoum history and timeline

- 2019–2024 Sudanese transition to democracy

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |