Alodia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alodia

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th century–c. 1500 | |||||||||||||

|

Possible flag according to the Catalan Atlas of 1375

|

|||||||||||||

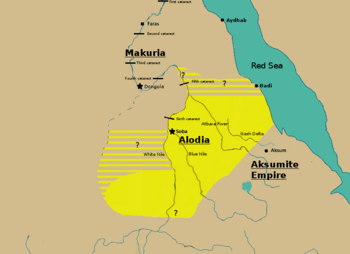

Estimated extent of Alodia in the 10th century

|

|||||||||||||

| Capital | Soba | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Nubian Meroitic(Possibly still spoken) Greek (liturgical) Others |

||||||||||||

| Religion | Coptic Orthodox Christianity Traditional African religion |

||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||

|

• First mentioned

|

6th century | ||||||||||||

|

• Destroyed

|

c. 1500 | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Today part of | Sudan Eritrea |

||||||||||||

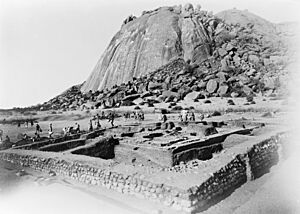

Alodia, also known as Alwa, was an important kingdom in Africa during the Middle Ages. It was located in what is now central and southern Sudan. Its capital city was Soba, which was close to modern-day Khartoum. Soba was built where the Blue and White Nile rivers meet.

Alodia was founded after the ancient Kingdom of Kush ended around 350 AD. We first find mentions of Alodia in history books in 569 AD. It was the last of three Nubian kingdoms to become Christian in 580 AD. The other two were Nobadia and Makuria. Alodia was likely at its strongest between the 9th and 12th centuries. Records show it was bigger and more powerful than its northern neighbor, Makuria. Alodia was a large kingdom with many different cultures. It was ruled by a strong king and governors he chose. Soba, the capital, was a busy trading city. It was described as having "extensive dwellings and churches full of gold and gardens." Goods came from Makuria, the Middle East, western Africa, India, and even China. People in Alodia were good at reading and writing in both Nubian and Greek.

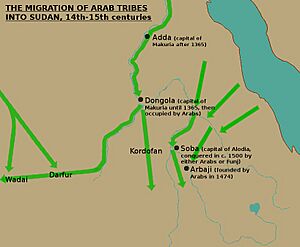

However, Alodia started to decline from the 12th century onwards. This might have been due to attacks from the south, dry weather, or changes in trade routes. In the 14th century, a terrible disease, possibly the plague, might have hit the country. At the same time, Arab tribes began to move into the Upper Nile valley. Around 1500, Soba was taken over by either Arabs or the Funj people. This event likely marked the end of Alodia. After Soba was destroyed, the Funj created the Sultanate of Sennar. This led to a period where Islam and the Arabic language became more common.

Contents

Exploring the Kingdom of Alodia

Where Was Alodia Located?

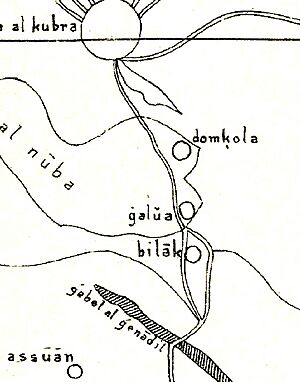

Alodia was part of a region called Nubia. In the Middle Ages, Nubia stretched from Aswan in southern Egypt to a point south of where the White and Blue Nile rivers meet. The main part of Alodia was the Gezira. This was a fertile plain between the White Nile to the west and the Blue Nile to the east. Many important Alodian archaeological sites, including Soba, are found in the Blue Nile Valley. We are not sure how far south Alodian influence reached. However, it probably bordered the Ethiopian highlands. The southernmost Alodian sites we know of are near Sennar.

West of the White Nile, there was a region called Al-Ahdin. This area was controlled by Alodia and is thought to be the Nuba Mountains. It might have even reached as far south as Jebel al Liri, near modern South Sudan.

The northern part of Alodia likely stretched from where the two Niles meet down to Abu Hamad. This area was probably the northern edge of an Alodian province called al-Abwab ("the gates").

Between the Nile and the Atbara rivers was the Butana. This was a grassland perfect for raising livestock. Many Christian sites have been found along the Atbara and the nearby Gash Delta (near Kassala). A king loyal to Alodia ruled the Gash Delta region. It seems that much of the borderlands between Sudan, Ethiopia, and Eritrea were under Alodian influence. These areas were once controlled by the Ethiopian Kingdom of Aksum. Alodia also controlled the desert along the Red Sea coast.

How Alodia Began

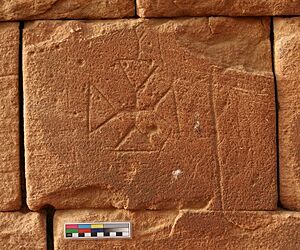

The name Alodia might be very old. It may have first appeared as Alut on a stone carving from the Kingdom of Kush around 4th century BC. It was also mentioned as Alwa by the Roman writer Pliny the Elder in the 1st century AD. He said it was south of Meroë. Another town named Alwa is in a 4th-century Aksumite inscription. This town was near where the Nile and Atbara rivers meet.

By the early 4th century, the Kingdom of Kush, which ruled much of Sudan's riverbanks, was weakening. People who spoke Nubian languages began to settle in the Nile Valley. They originally lived west of the Nile. But climate changes forced them east, leading to fights with Kush. By the mid-4th century, Nubians controlled most of the area Kush once ruled. An Aksumite inscription tells how the Nubians threatened the Aksumite kingdom. This led to an Aksumite army defeating the Nubians and marching to the Nile and Atbara rivers. There, they took goods from several Kushite towns, including Alwa.

Archaeological findings suggest the Kingdom of Kush ended in the mid-4th century. We don't know if the Aksumite attacks directly caused its fall. The Aksumites probably didn't stay long in Nubia. After this, new local centers grew, and their leaders were buried in large mounds. Such mounds in what became Alodia are found at El-Hobagi, Jebel Qisi, and perhaps Jebel Aulia. The mounds at El-Hobagi are from the late 4th century. They contained weapons, similar to Kushite royal burials. Many Kushite temples and settlements, including the old capital Meroë, seem to have been left empty. The Kushites themselves became part of the Nubian people, and their language was replaced by Nubian.

We don't know exactly how the Kingdom of Alodia started. But by the mid-6th century, it existed alongside the other Nubian kingdoms of Nobadia and Makuria. Soba became its capital and a major city by the 6th century. In 569, Alodia was first mentioned as a kingdom about to become Christian. A Greek document from Byzantine Egypt in the late 6th century also confirms Alodia's existence. It describes the sale of an Alodian slave girl.

Becoming Christian and Reaching its Peak

Alodia was the southernmost of the three Nubian kingdoms. It was the last to become Christian. In 580 AD, the King of Alodia asked for a bishop to baptize his people. This request was granted, and a missionary named Longinus was sent. The King, his family, and local leaders were baptized. This made Alodia part of the Christian world under the Coptic Patriarchate of Alexandria. After this, some non-Christian temples, like the one in Musawwarat es-Sufra, were likely turned into churches. We don't know how fast Christianity spread among all the people. It probably took a long time for people in rural areas to become Christian.

Between 639 and 641, Muslim Arabs took over Egypt from the Byzantine Empire. Makuria, which had joined with Nobadia, stopped two Muslim invasions. One was in 641/642 and another in 652. After these battles, Makuria and the Arabs signed a peace treaty called the Baqt. This treaty included a yearly exchange of gifts and rules for Arabs and Nubians. Alodia was specifically mentioned as not being affected by this treaty. While the Arabs could not conquer Nubia, they began to settle along the western Red Sea coast. They founded port towns like Aydhab and Badi in the 7th century. From the 9th century, they moved further inland, settling among the Beja in the Eastern Desert. Arab influence stayed east of the Nile until the 14th century.

Archaeological findings suggest that Soba, Alodia's capital, grew the most between the 9th and 12th centuries. In the 9th century, an Arab historian named al-Yaqubi described Alodia as the stronger of the two Nubian kingdoms. He said it took three months to travel across Alodia. He also noted that Muslims sometimes visited there.

A century later, in the mid-10th century, a traveler and historian named Ibn Hawqal visited Alodia. He wrote the most detailed account we have of the kingdom. He described Alodia's land and people in great detail. He made it sound like a large state with many different ethnic groups. He also noted its wealth, saying it had "an uninterrupted chain of villages and a continuous strip of cultivated lands." When Ibn Hawqal visited, the king was named Eusebius. After Eusebius died, his nephew Stephanos became king. Another Alodian king from this time was David, known from a tombstone in Soba.

Al-Aswani, an ambassador sent to Makuria, also traveled to Alodia. He confirmed Ibn Hawqal's descriptions of Alodia's geography. Like al-Yaqubi, he noted that Alodia was more powerful than Makuria. It was larger and had a bigger army. Soba was a rich town with "fine buildings, and extensive dwellings and churches full of gold and gardens." It also had a large Muslim area.

Abu al-Makarim (12th century) was the last historian to write much about Alodia. He still described it as a large Christian kingdom with about 400 churches. He mentioned a very large and beautiful church in Soba called the "Church of Manbali." Two Alodian kings, Basil and Paul, are mentioned in 12th-century Arabic letters.

There is evidence that the royal families of Alodia and Makuria were very close. It's possible that the throne often passed to a king whose father was from the other kingdom's royal family. Some historians believe the two kingdoms started to become closer in the early 8th century. In 943, al Masudi wrote that the Makurian king ruled Alodia. But Ibn Hawqal wrote the opposite. In the 11th century, a new royal crown appeared in Makurian art. It is thought to have come from the Alodian court. King Mouses Georgios, who ruled Makuria in the late 12th century, probably ruled both kingdoms at the same time. Since his royal title mentioned Alodia before Makuria, he might have been an Alodian king first.

The Decline of Alodia

Archaeological findings from Soba show that the city, and perhaps the Alodian kingdom, began to decline from the 12th century. By around 1300, Alodia's decline was well underway. No pottery or glass from after the 13th century has been found in Soba. Two churches were destroyed in the 13th century but rebuilt soon after. It is thought that Alodia was attacked by an African group called Damadim from the border region of modern Sudan and South Sudan. According to a geographer, they attacked Nubia in 1220. Soba might have been conquered and damaged at this time. In the late 13th century, another invasion from the south happened.

Economic problems also contributed to Alodia's decline. From the 10th to 12th centuries, new trading cities grew along the East African coast, like Kilwa. These cities competed with Nubia for trade. A period of severe droughts in Sub-Saharan Africa between 1150 and 1500 would also have hurt the Nubian economy. Evidence from Soba suggests the town suffered from too much grazing and farming.

By 1276, al-Abwab, once Alodia's northernmost province, became an independent kingdom. We don't know exactly how it broke away or what its relationship with Alodia was afterward. Pottery finds suggest al-Abwab continued to do well until the 15th or even 16th century. In 1286, a Mamluke prince sent messengers to several rulers in central Sudan. It is unclear if these rulers were still under the king in Soba. If not, it means Alodia had broken into many smaller states by the late 13th century.

During the 14th and 15th centuries, many Arab tribes moved into what is now Sudan. The Adal Sultanate also gained some influence in the area around Suakin. These nomadic groups might have benefited from the plague that may have hit Nubia in the mid-14th century. The plague killed many settled Nubians but not the nomadic Arabs. The Arabs then mixed with the local people, slowly taking control of land and people. The first recorded Arab migration to Nubia was in 1324. When Makuria broke apart in the late 14th century, it opened the way for more Arab migration. Many Arabs came from Egypt and followed the Nile. Others, who had lived among the Beja in the Eastern Desert, targeted Alodia, especially the Butana and Gezira regions.

At first, Alodia could control some of the new Arab groups, making them pay taxes. But the situation became harder as more Arabs arrived. By the second half of the 15th century, Arabs had settled throughout the central Sudanese Nile valley. Only the area around Soba was left of Alodia's land. In 1474, Arabs founded the town of Arbaji on the Blue Nile. This town quickly became an important center for trade and Islamic learning. Around 1500, the Nubians were politically divided. They had no single king but 150 independent lords ruling from castles along the Nile. Archaeology shows that Soba was mostly in ruins by this time.

The Fall of Alodia

It is not clear if the Kingdom of Alodia was destroyed by the Arabs under Abdallah Jammah or by the Funj, an African group from the south led by King Amara Dunqas. Most modern experts now agree it fell because of the Arabs.

Abdallah Jammah was an Arab leader. According to Sudanese stories, he came from the east and settled in the Nile Valley. He built up his power and made his capital at Qerri, north of where the two Niles meet. In the late 15th century, he gathered the Arab tribes to fight against Alodian rule. This was likely for religious and economic reasons. The Muslim Arabs no longer wanted to be ruled or taxed by a Christian ruler. Under Abdallah's leadership, Alodia and its capital Soba were destroyed. They took valuable treasures, like a "bejeweled crown" and a "famous necklace of pearls and rubies."

Another story says Soba was destroyed by Abdallah Jammah in 1509, after an earlier attack in 1474. The idea of uniting the Arabs against Alodia had been considered by an emir who lived between 1439 and 1459. His grandson, Emir Humaydan, crossed the White Nile. There, he met other Arab tribes and attacked Alodia. The king of Alodia was killed. But the "patriarch," likely the archbishop of Soba, escaped. He soon returned to Soba. A new king was crowned, and an army of Nubians, Beja, and Abyssinians was gathered to fight "for the sake of religion." Meanwhile, the Arab alliance was about to break apart. But Abdallah Jammah brought them back together. He also allied with the Funj king Amara Dunqas. Together, they finally defeated and killed the patriarch. They then destroyed Soba and enslaved its people.

The Funj Chronicle, a history of the Funj Sultanate, says King Amara Dunqas destroyed Alodia. He was also allied with Abdallah Jammah. This attack is dated to around 1396–1494. After this, Soba was said to be the capital of the Funj until Sennar was founded in 1504. Another history book, the Tabaqat Dayfallah, mentions that the Funj attacked and defeated the "kingdom of the Nuba" in 1504–1505.

Alodia's Lasting Impact

Some historians believe the fall of Soba was not the absolute end of Alodia. A Jewish traveler named David Reubeni visited the area in 1523. He said there was still a "Kingdom of Soba" on the eastern bank of the Blue Nile, even though Soba itself was in ruins. This matches stories from the Upper Blue Nile. These stories claim Alodia survived Soba's fall and continued to exist along the Blue Nile. It slowly moved to the mountains of Fazughli in the Ethiopian-Sudanese borderlands, forming the Kingdom of Fazughli. Recent digs in western Ethiopia seem to support the idea of an Alodian migration. The Funj eventually conquered Fazughli in 1685. Its people, known as Hamaj, became an important part of Sennar. They even took power in 1761–1762. As late as 1930, Hamaj villagers in the southern Gezira would swear by "Soba the home of my grandfathers and grandmothers."

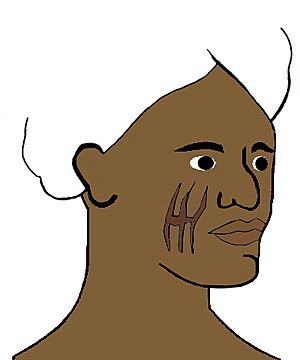

In 1504–1505, the Funj founded the Funj Sultanate. This included Abdallah Jammah's territory. The Funj kept some old Nubian customs. These included wearing crowns with features like horns, called taqiya umm qarnein. They also shaved the king's head when he was crowned.

After Alodia fell, many people adopted Arab culture and language. Nubians living along the Nile became part of Arab tribal systems. The Nubian language was spoken in central Sudan until the 19th century, when Sudanese Arabic replaced it. Sudanese Arabic still has many words from Nubian. Nubian place names can be found as far south as the Blue Nile state.

The fate of Christianity in the region is largely unknown. Church organizations likely collapsed with the kingdom. This led to a decline in Christian faith and the rise of Islam. Some Islamized groups from northern Nubia began to spread Islam in the Gezira. By 1523, King Amara Dunqas, who was originally not Muslim or only Christian in name, was recorded as Muslim. However, in the 16th century, many Nubians still considered themselves Christians. A traveler around 1500 confirmed this. But he also said Nubians lacked Christian teaching and knew little about the faith. In 1520, Nubian ambassadors asked the Ethiopian Emperor for priests. They said priests could no longer reach Nubia because of wars between Muslims. This led to a decline of Christianity in their land. Even in the 20th century, some practices with Christian origins were common in Omdurman, the Gezira, and Kordofan. These often involved using crosses on people and objects.

Soba remained inhabited until at least the early 17th century. Like many other ruined Alodian sites, it provided bricks and stones for nearby shrines dedicated to Sufi holy men. In the early 19th century, many remaining bricks from Soba were taken to build Khartoum, the new capital of Turkish Sudan.

How Alodia Was Governed

Information about Alodia's government is limited. But it was probably similar to Makuria's government. The king was the head of the state. He was said to be an absolute monarch. This means he had complete power. People would bow down to him. In Alodia, the next king was not the king's son. Instead, it was the son of the king's sister. This is called matrilineal succession.

The kingdom was divided into several provinces. These provinces were under the rule of Soba. The king's representatives likely governed these areas. The governor of the northern al-Abwab province was chosen by the king. This was similar to the Gash Delta region, which was ruled by an appointed Arabic speaker. In 1286, messengers were sent to several rulers in central Sudan. It is unclear if these rulers were truly independent or still under the king of Alodia. If they were still under the king, it would help us understand how the kingdom was organized. The ruler of al-Abwab seems to have been independent. Other regions mentioned include Al-Anag (possibly Fazughli), Ari, Barah, Befal, Danfou, Kedru, Kersa (the Gezira), and Taka (the Gash Delta region).

The state and the church were closely linked in Alodia. The Alodian kings probably supported the church. Old Coptic documents list several bishoprics (areas led by a bishop) in the Alodian kingdom: Arodias, Borra, Gagara, Martin, Banazi, and Menkesa. "Arodias" might refer to the bishopric in Soba. The bishops reported to the patriarch of Alexandria.

Alodia may have had a standing army. Cavalry (soldiers on horseback) likely showed the king's power in the provinces. Horses were also important for fast communication between the capital and the provinces. Besides horses, boats were also key for transportation.

| Name | When they Ruled | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Giorgios | ? | Found on a carving in Soba. |

| David | 9th or 10th century | Found on his tombstone in Soba. |

| Eusebios | c. 938–955 | Mentioned by Ibn Hawqal. |

| Stephanos | c. 955 | Mentioned by Ibn Hawqal. |

| Mouses Georgios | c. 1155–1190 | Ruled both Makuria and Alodia. |

| ?Basil | 12th century | Mentioned in an Arabic letter. |

| ?Paul | 12th century | Mentioned in an Arabic letter. |

Alodian Culture

Languages Spoken in Alodia

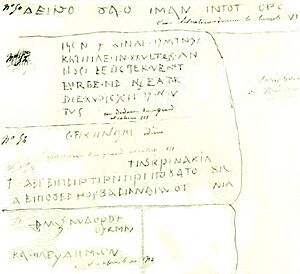

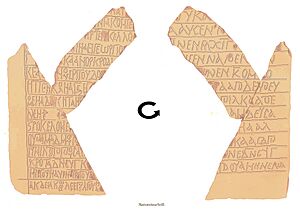

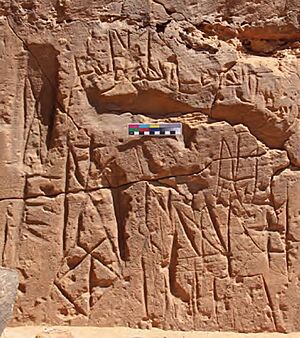

Alodia had many different ethnic groups, so many languages were spoken. But it was mainly a Nubian state, and most people spoke a Nubian language. Some writings found in Alodian territory suggest that Alodians spoke a different dialect from the Old Nobiin of northern Nubia. This dialect is sometimes called Alwan-Nubian. This idea comes from the way these writings were made. They used the Greek alphabet but had special characters based on Meroitic hieroglyphs. However, we still need to learn more about this language and how it relates to Old Nobiin. It seems to have disappeared by the 19th century, replaced by Arabic.

Although Greek was a respected religious language, it doesn't seem to have been spoken by many people. For example, the tombstone of King David from Soba is written in very good Greek. Al-Aswani noted that books were written in Greek and then translated into Nubian. Christian church services were also in Greek. Coptic was probably used to talk with the Patriarch of Alexandria, but there are very few written Coptic texts.

Besides Nubian, many other languages were spoken throughout the kingdom. In the Nuba mountains, several Kordofanian languages were spoken, along with Hill Nubian dialects. Upstream along the Blue Nile, Eastern Sudanic languages like Berta or Gumuz were spoken. In the eastern areas lived the Beja, who spoke their own Cushitic language. The Semitic Arabs and the Tigre also spoke their own languages.

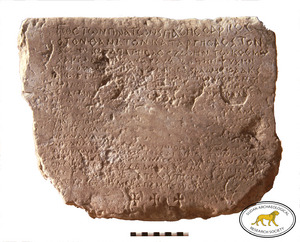

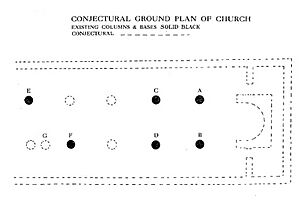

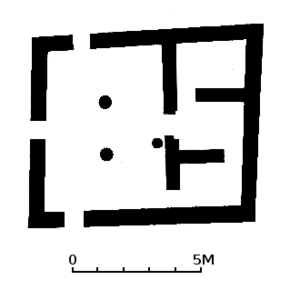

Church Buildings in Alodia

Historical records mention 400 churches throughout the kingdom. Most of them have not been found yet. Only seven have been identified so far. These are called church "A", "B", "C", "E", the "Mound C" church in Soba, the church in Saqadi, and the temple-church in Musawwarat as-Sufra. Churches "A"–"C" and the "Mound C" church were basilicas, similar to the largest churches in Makuria. The Saqadi church was built inside an older structure. Church "E" and the church of Musawwarat es-Sufra were "normal" churches. So, the known Alodian churches can be put into three types.

On "Mound B" in Soba, there was a group of three churches: "A", "B", and "C". Churches "A" and "B", likely built in the mid-9th century, were large buildings. Church "C" was much smaller and built later, probably after 900. The three churches had many things in common. They all had a narthex (an entrance hall), wide entrances on the main east-west line, and a pulpit (a raised stand for speaking) along the north side of the nave (the main part of the church). This complex was probably the main church center of Soba, and perhaps the whole kingdom.

Church "E" was on a natural hill. It was 16.4 by 10.6 meters in size. Its layout was unusual, with an L-shaped narthex. The roof was held up by wooden beams resting on stone pedestals. The inside walls were covered with painted white mud. The outside walls were covered in white lime mortar.

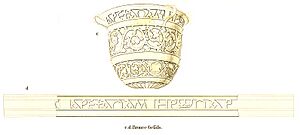

The "Mound C" church, possibly the oldest church in Soba, was about 13.5 meters long. It was the only Alodian church known to have stone columns. Very little of it remains. Five capitals (the tops of columns) have been found. They belong to a style that appeared in Nubia around the 8th century.

The church of Musawwarat es-Sufra, called "Temple III A", was first a non-Christian temple. It was turned into a church probably soon after the king became Christian in 580. It was rectangular and slightly uneven in shape. It had one large room and three small rooms. The roof was supported by wooden beams. Even though it was originally a Kushite temple, it still had similarities to churches built for Christian worship. For example, it had an entrance on both the north and south sides.

The southernmost known Nubian church was in Saqadi. It was a red brick building placed inside an older building. It had a nave, two L-shaped walls, and at least two aisles with rectangular brick pillars. It also had three rooms at the western end, which was a typical Nubian style.

Nubian church architecture was greatly influenced by Egypt, Syria, and Armenia. The group of churches at "Mound B" might show influences from the Byzantine Empire. Alodian churches did not have eastern entrances or tribunes, which were common in northern Nubian churches. Also, Alodian churches used more wood.

Pottery Styles

In medieval Nubia, pottery and its decorations were seen as an art form. Until the 7th century, the most common pottery in Soba was "Red Ware." These were round bowls made on a potter's wheel. They had a red or orange slip (a thin coating of clay) and were painted with designs like boxes, flowers, or crosses. The outlines were black, and the insides were white. Their design continued Kushite styles, possibly with influences from Aksumite Ethiopia. Because they are rare, it's thought they were imported.

"Soba Ware" was a type of pottery made on a wheel with unique decorations. The shapes of the pottery were varied, as were the painted designs. One special feature was the use of faces as decoration. These faces were simple, almost geometric, with big round eyes. This style was different from Makuria and Egypt. But it looked similar to paintings and manuscripts from Ethiopia. It's possible the potters copied these designs from church murals. Another unique feature was the use of animal-shaped bumps (protomes). Glazed vessels were also made. They copied Persian aquamaniles (water containers) but were not as high quality. From the 9th century, "Soba Ware" was slowly replaced by fine pottery imported from Makuria.

Alodia's Economy

Farming and Food

Alodia was in the savannah belt, which gave it an economic advantage over Makuria to the north. According to al-Aswani, the food for Alodia and its king came from Kersa, which is thought to be the Gezira region. North of where the two Niles meet, farming was limited to areas along the river. Farmers used tools like the shadoof (a water-lifting device) or the more complex sakia (a waterwheel). In contrast, farmers in the Gezira had enough rainfall for rain-fed farming, which was their main source of income.

Archaeological records show what kinds of food were grown and eaten in Alodia. In Soba, the main grain was sorghum. Barley and millet were also eaten. Al-Aswani noted that sorghum was used to make beer. He also said that vineyards (places where grapes are grown) were rare in Alodia compared to Makuria. There is archaeological evidence of grapes. According to al-Idrisi, onions, horseradish, cucumbers, watermelons, and rapeseed were also grown, but none were found in Soba. Instead, figs, acacia fruits, doum palm fruits, and dates have been identified.

Alodia's agriculture included both settled farmers and nomadic people who raised animals. These two groups helped each other by trading goods. Al-Aswani wrote that beef was plentiful in Alodia, thanks to its good grazing land. Archaeological evidence from Soba shows that cattle were very important there. Most animal bones found are from cattle, followed by sheep and goats. Chickens were probably also raised in Soba. No remains of pigs have been found. Camel remains have been noted, but they don't show signs of being butchered for food. Fishing and hunting were only small parts of the diet in Soba.

Trade Routes and Goods

Trade was an important way for Alodian people to earn money. Soba was a major trading center with routes going north-south and east-west. Goods came into the kingdom from Makuria, the Middle East, western Africa, India, and China. Trade with Makuria probably went through the Bayuda Desert. Another route went from near Abu Hamad to Korosko in Lower Nubia. A route going east started near Berber and ended in Badi, Suakin, and Dahlak. A merchant named Benjamin of Tudela mentioned a route going west, from Alodia to Zuwila in Fezzan. There is little archaeological evidence for trade with Ethiopia, but other evidence suggests they traded. Trade with the outside world was mainly handled by Arab merchants. Muslim merchants traveled through Nubia, and some lived in a special area in Soba.

Alodia likely exported raw materials like gold, ivory, salt, and other tropical products, as well as animal hides. According to one story, Arab merchants came to Alodia to sell silk and textiles. In return, they received beads, elephant tusks, and leather. In Soba, silk and flax have been found, both probably from Egypt. Most of the glass found there was also imported. Benjamin of Tudela claimed merchants traveling from Alodia to Zuwila carried hides, wheat, fruits, legumes, and salt. On their return, they carried gold and precious stones.

Slaves are often thought to have been exported by medieval Nubia. Some historians suggest Alodia was a state that specialized in trading slaves. They might have taken people from non-Christian groups to the west and south. However, there is very little evidence for a regulated slave trade. Such evidence only starts to appear in the 16th century, after the Christian kingdoms fell.

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |