Makuria facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Makuria

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th century–1518 Late 15th/16th century |

|||||||||||||

|

The flag of Makuria according to the Book of Knowledge of All Kingdoms. c. 1350

|

|||||||||||||

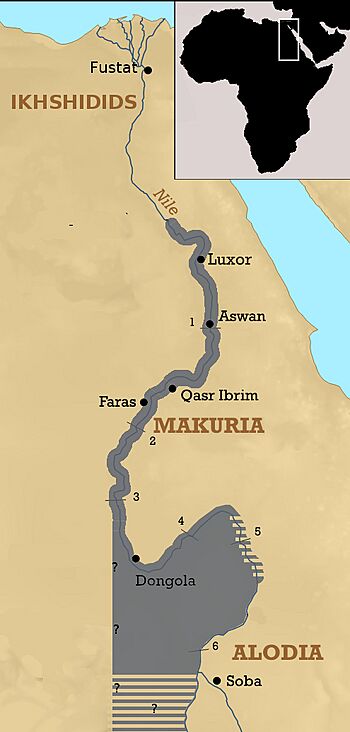

The Kingdom of Makuria at its maximum territorial extent around 960, after a raid that reached as far north as Akhmim

|

|||||||||||||

| Capital | Dongola (until 1365) Gebel Adda (from 1365) |

||||||||||||

| Common languages | Nubian Coptic Greek Arabic |

||||||||||||

| Religion |

|

||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

|

• fl. 651–652

|

Qalidurut (first known king) | ||||||||||||

|

• fl. 1463–1484

|

Joel (last known king) | ||||||||||||

|

• c. 1520–1526

|

Queen Gaua (new last known ruler) | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

5th century | ||||||||||||

|

• Royal court fled to Gebel Adda, Dongola abandoned

|

1365 | ||||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

1518 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Gold

Solidus Dircham |

||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Today part of | Sudan Egypt |

||||||||||||

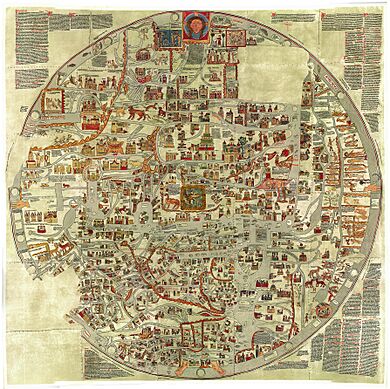

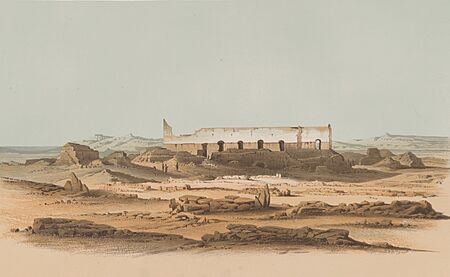

Makuria was a powerful medieval kingdom in Nubia, a region in what is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt. Its capital city was Dongola. The kingdom is sometimes called by its capital's name.

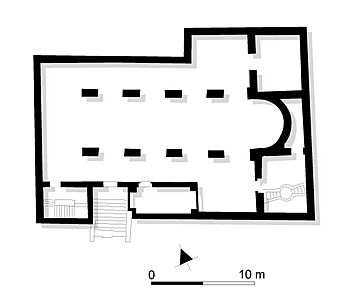

Makuria began after the Kingdom of Kush fell apart in the 4th century. It stretched along the Nile Valley from the 3rd Nile cataract south to Mograt Island. Dongola was founded around 500 AD. By the mid-6th century, Makuria became a Christian kingdom. In the early 7th century, it took over its northern neighbor, Nobatia. This made Makuria share a border with Byzantine Egypt.

In 651, an Arab army tried to invade Makuria. But the Nubians fought them off. A peace treaty called the Baqt was signed. This treaty stopped further Arab invasions. In return, Makuria sent 360 slaves to Egypt each year. This agreement lasted for centuries.

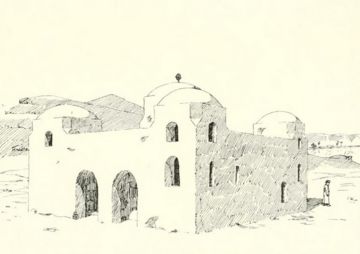

From the 9th to the 11th century, Makuria was at its strongest. Many impressive buildings were constructed, like the Throne Hall of Dongola and the great Cruciform Church in Dongola. The Banganarti monastery was also built. Art like wall paintings and beautiful pottery became very popular. The Nubian language became widely used for writing. Other languages used were Coptic, Greek, and Arabic. Makuria also had close ties with the kingdom of Alodia to its south. It also had some influence in Upper Egypt and northern Kordofan.

Makuria started to decline in the 13th and 14th centuries. This was due to attacks from Mamluk Egypt, internal problems, and possibly the plague. Trade routes also changed. In the 1310s and 1320s, Muslim kings briefly ruled Makuria. A civil war in 1365 made the kingdom much smaller. It lost many southern lands, including Dongola. The last known king lived in the late 15th century, likely in Gebel Adda. Makuria finally disappeared by the 1560s. At that time, the Ottomans took over Lower Nubia. The southern parts of Makuria, including Dongola, were taken by the Islamic Funj Sultanate in the early 16th century.

Contents

History of Makuria

Early Years (5th–8th Century)

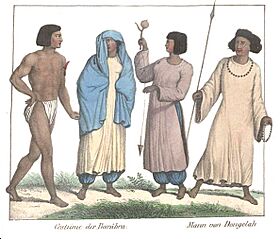

By the early 4th century, the Kingdom of Kush was falling apart. The area that would become Makuria was likely already separate from Kush. A unique culture developed here. During the 4th and 5th centuries, Napata became a center for new leaders. They were buried in large mounds called tumuli, like those at el Zuma or Tanqasi. The population grew, and the Kushites mixed with the Nubians. The Nubians were a group from Kordofan who had settled in the Nile Valley. This led to the creation of the Makurian society and state by the 5th century.

In the late 5th century, a Makurian king moved the capital from Napata. The new capital was Dongola, where a fortress was built. Many more fortresses were built along the Nile. These were likely meant to help cities grow, not just for defense.

Makuria had connections with the Byzantine Empire early on. In the 530s, the Byzantine Emperor Justinian wanted to expand his influence. He planned to make the Nubians Christian to gain allies against the Persians. In 543, Christian missionaries arrived in Nubia. Makuria became Christian in the mid-6th century. In 573, a Makurian group visited Constantinople. They brought ivory and a giraffe, showing their good relationship with the Byzantines. Makuria adopted the Chalcedonian Christian faith. This was different from Nobatia to the north, which was Miaphysite. Early churches in Dongola show strong ties with the Byzantine Empire. Trade between the two states was strong.

In the 7th century, Makuria took over Nobatia. This likely happened after the Persians invaded Egypt in the 620s. Nobatia was weakened by the fall of Egypt. Makuria then stretched north to Philae. A new bishopric was created in Faras around 630. Nobatia remained a separate area within Makuria, ruled by an Eparch.

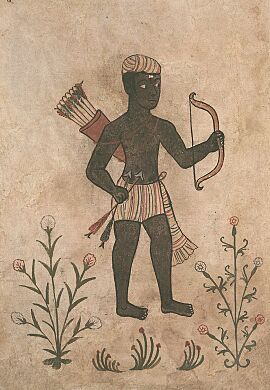

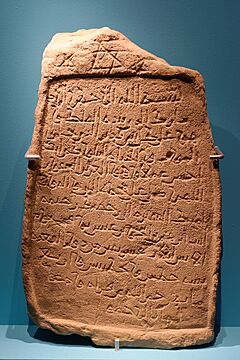

Between 639 and 641, Muslim Arabs took over Byzantine Egypt. In 641 or 642, the Arabs sent an army into Makuria. But the Nubians defeated them. A second invasion came in 651/652, led by Abd Allah ibn Sa'd ibn Abi al-Sarh. The Arabs reached Dongola and attacked it with catapults. They damaged parts of the city but could not break through the citadel walls. Muslim sources praised the skill of the Nubian archers in defending their city.

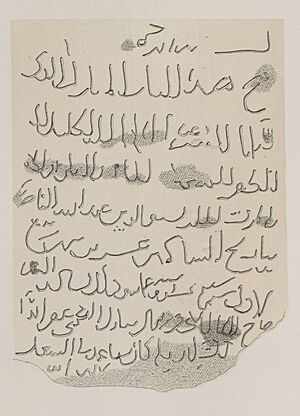

Since neither side could win, the Arab leader and Makurian king Qalidurut signed a treaty called the Baqt. This was a ceasefire and an agreement to exchange goods every year. Makuria sent slaves, and Egypt sent wheat and textiles. This treaty was not a sign of Makuria giving up. Makuria was recognized as an independent state. It was one of the few states to stop the Arabs during their early expansion. The Baqt lasted for over six centuries, though it was sometimes broken by raids.

The 8th century was a time of stability. Under King Merkurios, who ruled around 700 AD, the kingdom was reorganized. Miaphysite Christianity became the official religion. He also likely founded the large Ghazali monastery. In 747, the Coptic Patriarch was imprisoned in Egypt. Makuria invaded Egypt and besieged Fustat, the Egyptian capital. The Patriarch was then released. This shows Makuria's strong influence in Upper Egypt. In 750, the sons of the last Umayyad Caliph fled to Nubia. But King Kyriakos did not give them shelter.

Golden Age (9th–11th Century)

Makuria reached its peak between the 9th and 11th centuries. In the early 9th century, King Ioannes stopped paying the Baqt to Egypt. When he died in 835, an Arab envoy demanded 14 years of missed payments. The new king, Zakharias III, sent his son Georgios I to Baghdad to negotiate. Georgios's journey was famous. He rode a camel, carried a scepter and a golden cross, and had a red umbrella carried over his head. He was joined by a bishop, horsemen, and slaves.

Georgios was educated and polite. He convinced the caliph to forgive Makuria's debts. He also reduced the Baqt payments to every three years. Georgios returned to Nubia in 836 or 837. After his return, the new Cruciform Church was built in Dongola. It was about 28 meters (92 feet) tall and the largest building in the kingdom. A new palace, the Throne Hall of Dongola, was also built. It showed strong Byzantine influences.

In 831, the Abbasid caliph defeated the Beja east of Nubia. This extended Muslim rule over the Sudanese Eastern Desert. In the mid-9th century, an Arab adventurer named al-Umari settled near a gold mine in eastern Makuria. He occupied Makurian lands along the Nile. King Georgios I sent his son to fight al-Umari, but he failed. Eventually, another son, Zacharias, defeated al-Umari.

During the rule of the Ikhshidid dynasty in Egypt, relations with Makuria worsened. In 951, a Makurian army attacked Egypt's Kharga Oasis. They killed and enslaved many people. Five years later, Makurians attacked Aswan. They were chased back to Qasr Ibrim. Another Makurian attack on Aswan followed, and the Egyptians captured Qasr Ibrim. But Makurian attacks continued. Between 962 and 964, they pushed north to Akhmim. Parts of Upper Egypt were occupied by Makuria for several years.

In 969, the Fatimid Caliphate conquered Egypt. They immediately sent an envoy, Ibn Salim al-Aswani, to King Georgios III. Georgios agreed to restart the Baqt payments. But he refused to convert to Islam. Instead, he invited the Fatimid governor of Egypt to become Christian. Relations between Makuria and Fatimid Egypt remained peaceful. The Fatimids needed the Nubians as allies against their enemies.

Makuria also influenced the Nubian-speaking people of Kordofan. Makuria seemed to have a close connection with the southern Nubian kingdom of Alodia. This was like a family union. Archaeological findings show Makurian influence on Alodian art and buildings from the 8th century. There is little evidence of contact with Christian Ethiopia. However, King Georgios III helped solve a problem between the Patriarch of Alexandria and an Ethiopian ruler. Ethiopian monks traveled through Nubia to reach Jerusalem. They also brought knowledge of Nubian architecture to Ethiopia.

In the second half of the 11th century, Makuria had major cultural and religious changes. This was called "Nubization." Archbishop Georgios of Dongola likely led these changes. He made the Nubian language popular for writing. This helped counter the growing influence of Arabic in the Coptic Church. He also introduced the worship of dead rulers and Nubian saints. A new, unique church was built in Banganarti. It became one of the most important churches in the kingdom. Makuria also adopted new royal clothing and titles, possibly from Alodia.

Decline and End (12th Century–1518)

In 1171, Saladin overthrew the Fatimid dynasty in Egypt. This led to new conflicts between Egypt and Nubia. The next year, a Makurian army attacked Aswan. Saladin sent his brother Turan-Shah to deal with the Nubians. Turan-Shah captured Qasr Ibrim in January 1173. He reportedly looted it, took prisoners, and turned the church into a mosque. King Moses Georgios, who likely ruled both Makuria and Alodia, was confident. He branded a cross on the Egyptian envoy's hand. Turan Shah left Nubia but left Kurdish troops in Qasr Ibrim. These troops raided Lower Nubia for two years. In 1175, a Nubian army arrived to fight the invaders. The Kurdish commander drowned while crossing the Nile, and Saladin's troops left Nubia. Peace returned for 100 years.

There are no records from travelers to Makuria between 1172 and 1268. This period is a mystery. But Makuria seems to have declined sharply. Some historians blame Bedouin invasions. Other reasons might include changes in African trade routes and a long dry period.

Things changed with the rise of the Mamluks in 1260. In 1265, a Mamluk army reportedly raided Makuria as far south as Dongola. In 1272, King David attacked the port town of Aidhab. This town was important for pilgrims going to Mecca. The Nubian army destroyed the town. The Mamluks sent an army in response, but it did not go far. Three years later, Makurians attacked Aswan again. Mamluk Sultan Baybars responded with a strong army in 1276. They defeated the Nubians in three battles, including the Battle of Dongola. King David fled south. But the king of al-Abwab handed David over to Baybars, who had him executed.

Europe became more aware of Christian Nubia during the 12th and 13th centuries. There were even ideas to ally with the Nubians for a new crusade against the Mamluks. Nubian characters appeared in crusader songs. They were first shown as Muslims, then as Christians. Crusaders and pilgrims met Nubians in Jerusalem and Egypt. Some Genoese traders were even present in Dongola.

Internal problems also hurt the kingdom. King David's cousin, Shekanda, claimed the throne. He sought Mamluk support. In 1276, the Mamluks put Shekanda on the throne. Shekanda, a Christian, made Makuria a vassal of Egypt. A Mamluk army was stationed in Dongola. A few years later, Shamamun, another royal family member, led a rebellion. He defeated the Mamluk army and took the throne in 1286. He offered the Egyptians more Baqt payments to end the vassal agreement. The Mamluks agreed.

After some peace, King Karanbas stopped the payments. The Mamluks occupied Makuria again in 1312. This time, a Muslim from the Makurian royal family, Sayf al-Din Abdullah Barshambu, was put on the throne. He began converting the nation to Islam. In 1317, the throne hall of Dongola became a mosque. Other Makurian leaders did not accept this. The nation fell into civil war. Barshambu was killed and replaced by Kanz ad-Dawla. His tribe, the Banu Khanz, ruled as puppets of the Mamluks. King Karanbas tried to take control in 1323. He briefly seized Dongola but was ousted a year later.

Many thought the conversion of the throne hall marked the end of Christian Makuria. But Christianity remained strong. Both Muslim and Christian kings ruled Makuria. The traveler Ibn Battuta and historian Shihab al-Umari said the kings were Muslim, but most people were Christian. An Ethiopian monk in 1330 said the Nubian king he met was Christian. The Book of Knowledge of All Kingdoms from the mid-14th century said Dongola was Christian. It also said its flag was a cross on a white background. Records show three Makurian kings in the 1330s and mid-14th century. One of them, Siti, still controlled a large Christian territory.

Around 1347, the plague devastated Nubia. Archaeology shows a rapid decline of Christian Nubian civilization after this. The plague might have wiped out entire Nubian communities.

In 1365, another civil war happened. The king was killed by his nephew, who allied with the Banu Ja'd tribe. The king's brother fled to Gebel Adda in Lower Nubia. The nephew then killed the Banu Ja'd nobility and destroyed Dongola. He then went to Gebel Adda to ask his uncle for forgiveness. Dongola was left to the Banu Ja'd, and Gebel Adda became the new capital.

Final Years (1365–Late 15th Century)

The Smaller Makurian Kingdom

The kings in Gebel Adda continued their Christian traditions. They ruled a smaller kingdom, about 100 km (62 miles) long. This kingdom was called Dotawo in Old Nubian. The Mamluks left this smaller kingdom alone because it was not strategically important.

The last known king was Joel. He is mentioned in documents from 1463 and 1484. The kingdom might have had a brief revival under Joel. After Joel, the kingdom may have collapsed. The cathedral of Faras and Qasr Ibrim were no longer used after the 15th century. The palace of Gebel Adda also stopped being used. In 1518, there is one last mention of a Nubian ruler. However, in 2023, a Christian Nubian Queen Gaua was found to have ruled in the 1520s. By the 1560s, there was no independent Christian kingdom. The Ottomans took over Lower Nubia. The Funj Sultanate took over Upper Nubia.

Later Changes

Political Changes

By the early 15th century, there was a king of Dongola. He was likely independent from Egypt. These new kings probably faced many Arab migrations. They were too weak to conquer the smaller Makurian state in Lower Nubia.

Some small kingdoms might have continued Christian Nubian culture. One example is on Mograt island. Another was the Kingdom of Kokka, founded in the 17th century. Its traditions were similar to Christian times. Its kings were Christian until the 18th century. In 1412, the Awlad Kenz took control of Nubia.

People and Languages

Nubians living upstream of Al Dabbah began to adopt Arabic identity and language. They became the Ja'alin, who claim to be descendants of Abbas, Muhammad's uncle. The Ja'alin were mentioned in the early 16th century. Nubian remained a spoken language among them until the 19th century. North of Al Dabbah, three Nubian groups developed: the Kenzi, Mahasi, and Danagla. The Danagla still speak a Nubian language, Dongolawi. North Kordofan also became Arabic-speaking. Its locals were mainly Nubian-speaking until the 19th century.

Today, Arabic is replacing the Nubian language. Many Nubians now claim to be Arabs, forgetting their Christian Nubian past.

Makurian Culture

Christian Nubia was once thought to be a simple place. This was because their graves were small and lacked expensive items. But modern scholars know that Makurians had rich and lively arts and culture. This was due to different cultural practices.

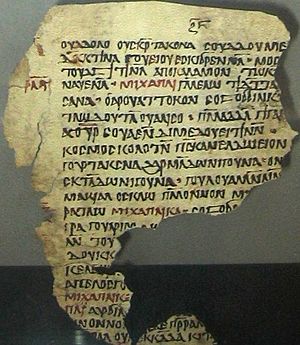

Languages Used

Four languages were used in Makuria: Nubian, Coptic, Greek, and Arabic. Nubian had two dialects: Nobiin in the north and Dongolawi in the heartland. The royal court used Nobiin, even though it was in Dongolawi-speaking territory. By the 8th century, Nobiin was written using the Coptic alphabet. By the 11th century, Nobiin was used for official, business, and religious documents.

The Coptic language declined in Makuria and Egypt. Before Nobiin, Coptic might have been the official language, but this is uncertain. Coptic was common in Nobadia and used for communication with Egypt. Coptic refugees settled in Makuria. Nubian priests studied in Egyptian monasteries. Greek was a very respected language used in religious texts. But it was likely not spoken much. Arabic was used from the 11th and 12th centuries. It replaced Coptic for trade and diplomatic letters with Egypt. Arab traders and settlers were in northern Nubia. But their spoken language slowly changed from Arabic to Nubian.

Makurian Arts

Wall Paintings

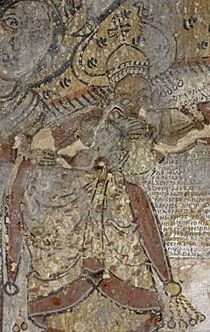

About 650 murals have been found at 25 sites. More paintings are still being studied. A very important discovery was the Cathedral of Faras. It was filled with sand, which preserved many paintings. Similar paintings were found in palaces and homes. They show what Makurian art was like. The style was greatly influenced by Byzantine art. It also had influences from Egyptian Coptic art and Palestine. Most paintings were religious. They showed common Christian scenes. They also showed Makurian kings and bishops, who had noticeably darker skin than the Biblical figures.

- Gallery

-

Saint Peter in a Pharaonic painting, Wadi es-Sebua (late 7th-early 8th century)

-

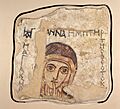

St. Anne, Faras (8th-early 9th century)

-

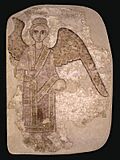

Archangel Gabriel with sword, Faras (9th-early 10th century)

-

Three youths in the furnace, Faras (late 10th century)

-

Bishop Marianos with Madonna and Christ Child, Faras (early 11th century)

Manuscript Illustrations

Pottery

Nubian pottery is considered one of the richest local pottery traditions in Africa. It is divided into three periods. The early period (550 to 650 AD) had simple pottery, similar to late Roman Empire styles. Much pottery was imported from Egypt. After 652, local production increased. In the middle period (until around 1100 AD), pottery was painted with flowers and animals. It showed influences from Umayyad and Sassanian art. In the late period, during Makuria's decline, local production fell again. Pottery became less decorated, but better firing techniques allowed for different clay colors.

Role of Women

Christian Nubian society was matrilineal. This means that family lines and inheritance often passed through the mother. Women had a high social standing. The queen mother and the king's sister (who would become the next queen mother) were very important politically. They often appeared in legal documents. Another female title was asta ("daughter"), possibly a local representative.

Women could get an education. There is evidence that female scribes existed, similar to Byzantine Egypt. Both men and women could own, buy, and sell land. Land transfers from mother to daughter were common. Women could also support churches and wall paintings. Inscriptions from the Faras cathedral show that about half of the wall paintings had a female sponsor. An inscription from Faras suggests that women could also serve as deacons in the church.

Hygiene

Toilets were common in Nubian homes. In Dongola, all houses had ceramic toilets. Some houses had private toilets connected to a small room with a window for cleaning and a ventilation shaft. Biconical clay pieces were used like toilet paper.

One house in Dongola had a vaulted bathroom. It was supplied with water by pipes from a water tank. A furnace heated the water and air. The warm air circulated into the decorated bathroom through wall flues. The Ghazali monastery may have had several bathrooms.

Government and Kings

Makuria was a monarchy ruled by a king in Dongola. The king was also seen as a priest and could perform mass. How new kings were chosen is not fully clear. Early writings suggest it was from father to son. But after the 11th century, it seems Makuria used the uncle-to-sister's-son system, which was common in Kush.

Little is known about government below the king. Many officials with Byzantine titles are mentioned, but their exact jobs are unknown. The Eparch of Nobatia was an important figure. He seemed to be the governor of Nobatia after it joined Makuria. The Eparch was also in charge of trade and diplomacy with Egypt. At first, the king appointed the Eparch. Later, the position became hereditary.

The elite of Makuria were noblemen, called "princes" by Islamic sources. They were courtiers, military leaders, and bishops. They were powerful enough to express unhappiness and even remove a ruler if they disagreed with him. A select group of elders formed a council that advised the king. The queen mother also played a key role in advising the king. In 1292, a Makurian king reportedly said that "only the women direct the kings."

bishops might have had a role in governing. Ibn Selim el-Aswani noted that the king met with a council of bishops before responding to his mission. Some writers said Makuria was a federation of thirteen kingdoms. The great king in Dongola ruled over them.

Kings of Makuria

Religion in Makuria

Old Beliefs

Before the 5th century, the old faith of Meroe was strong. In the 5th century, Nubians even invaded Egypt. This happened when Christians there tried to turn temples into churches. Some Nubians seemed to remain pagan until the 10th century. One report said some "do not know the Creator and adore the Sun and the Day."

Christianity in Makuria

Archaeological findings show Christian items in Nubia during this period. Some scholars think this means people were already converting. Others believe these items just came from Christian Egypt.

The official conversion came with missions in the 6th century. The Byzantine Empire sent a group to convert the kingdoms to Chalcedonian Christianity. But Empress Theodora reportedly delayed them. This allowed a group of Miaphysites to arrive first. The Miaphysites successfully converted Nobatia and Alodia. Makuria, however, remained Chalcedonian Christian.

Archaeological evidence points to a quick conversion. Old traditions, like building elaborate tombs and burying expensive items with the dead, stopped. Temples were turned into churches. Churches were eventually built in almost every town and village.

By around 710 AD, Makuria officially became Coptic. It was loyal to the Coptic Patriarch of Alexandria. The king of Makuria became the protector of the Patriarch. He sometimes used military force to protect him, as Kyriakos did in 722. Makuria, which was Chalcedonian, absorbed Nobatia, which was Coptic. Historians wonder why the conquering state adopted the religion of its rival. It is likely that Egyptian Coptic influence was much stronger in the region.

Church Organization

The Makurian church had seven bishoprics: Kalabsha, Qupta, Qasr Ibrim, Faras, Sai, Dongola, and Suenkur. Unlike Ethiopia, there was no national church. All seven bishops reported directly to the Coptic Patriarch of Alexandria. The Patriarch appointed the bishops. But they were mostly local Nubians, not Egyptians.

Monasteries

There is not much evidence for monasteries in Makuria. Only three archaeological sites are confirmed as monasteries. They are small and very Coptic. This suggests they might have been set up by Egyptian refugees. From the 10th or 11th century, Nubians had their own monastery in Egypt's Wadi El Natrun valley.

Islam in Makuria

The Baqt treaty allowed Muslims to travel safely in Makuria. But it said they could not settle there. However, this rule was not always followed. Muslim migrants, likely merchants and craftspeople, settled in Lower Nubia from the 9th century. They married locals, creating a small Muslim population. Arabic documents show these Muslims had their own judges. But they still recognized the Eparch of Nobatia as their ruler. They likely had mosques, but none have been clearly found by archaeologists, except possibly in Gebel Adda.

In Dongola, there were not many Muslims until the late 13th century. Before that, only merchants and diplomats were Muslim. In the late 10th century, when al-Aswani visited Dongola, there was no mosque. He and about 60 other Muslims had to pray outside the city. A mosque is only clearly recorded in 1317, when Abdallah Barshambu converted the throne hall.

The Jizya, a tax on non-Muslims, was introduced after the Mamluk invasion of 1276. Makuria was sometimes ruled by Muslim kings. But most Nubians remained Christian. The real spread of Islam in Nubia began in the late 14th century. This was when Muslim teachers started to arrive.

Makurian Economy

The main economic activity in Makuria was farming. Farmers grew several crops a year, including barley, millet, and dates. They used farming methods that had been around for thousands of years. Small plots of land along the Nile were irrigated and fertilized by the river's yearly floods. A key invention was the saqiya. This was an oxen-powered water wheel that helped increase harvests and population. Land was divided into individual plots, not large estates. Farmers lived in small villages with houses made of sun-dried brick.

Important industries included pottery production in Faras and weaving in Dongola. Smaller local industries included leatherworking, metalworking, and making baskets, mats, and sandals from palm fiber. Gold mined in the Red Sea Hills was also important.

Cattle were very important for the economy. Their breeding and selling might have been controlled by the government. A large collection of 13th-century cattle bones from Old Dongola suggests a mass slaughter by the invading Mamluks. They likely did this to weaken Makuria's economy.

Makurian trade was mostly done by bartering goods. The state never used its own currency, but Egyptian coins were common in the north. Trade with Egypt was very important. Makuria imported many luxury and manufactured goods from Egypt. Makuria's main export was slaves. These slaves were not from Makuria itself. They came from further south and west in Africa.

Little is known about Makurian trade with other parts of Africa. There is some evidence of trade with areas to the west, especially Kordofan. Contacts with Darfur and Kanem-Bornu seem likely, but there is little proof. Makuria also had important political ties with Christian Ethiopia to the southeast. For example, in the 10th century, Georgios II helped the Ethiopian ruler. He convinced the Patriarch Philotheos of Alexandria to appoint an abuna, or bishop, for the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. However, there is little evidence of much other interaction between the two Christian states.

|

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |