Hyksos facts for kids

The Hyksos were kings who ruled parts of Ancient Egypt during the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt (around 1650–1550 BC). Their main city was Avaris, located in the Nile Delta. From Avaris, they controlled Lower Egypt and parts of Middle Egypt.

Long ago, a historian named Manetho wrote that the Hyksos were invaders who attacked Egypt. However, modern historians and archaeologists believe they were mostly people from the Levant (an area in the Middle East, like modern-day Canaan) who slowly settled in the Nile Delta. They might have taken control as the Egyptian government became weaker.

The Hyksos period was the first time foreign rulers controlled Egypt. Many details about their rule, like how big their kingdom was, are still a bit of a mystery. The Hyksos mixed their own customs from the Levant with many Egyptian traditions. They are often credited with bringing new technologies to Egypt, such as the horse and chariot. They might also have introduced the sickle sword and the composite bow, though this is still debated.

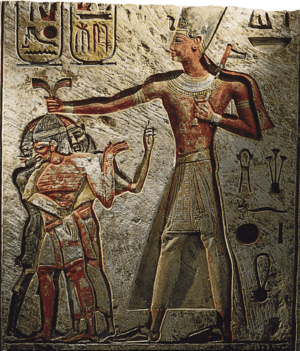

The Hyksos did not rule all of Egypt. They shared the land with Egyptian pharaohs from the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Dynasties, who ruled from Thebes. Eventually, the Theban pharaohs fought the Hyksos. This conflict ended with the defeat of the Hyksos by Ahmose I, who then started the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. After their defeat, Egyptians often described the Hyksos as cruel foreign rulers.

Contents

What Does "Hyksos" Mean?

The Name's Origin

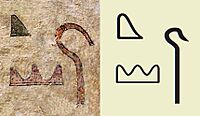

Quick facts for kids Hyksos in hieroglyphs |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ḥqꜣ-ḫꜣsw / ḥqꜣw-ḫꜣswt, "heqau khasut" "Hyksos" Ruler(s) of the foreign countries |

||||||||

| Greek | Hyksos (Ὑκσώς) Hykussos (Ὑκουσσώς) |

|||||||

| This shows the hieroglyphs for "Hyksos." The first sign means "ruler," and the last two mean "foreign country." | ||||||||

The word "Hyksos" comes from a Greek word, which itself came from an ancient Egyptian phrase: ḥqꜣw-ḫꜣswt. This Egyptian phrase means "rulers of foreign lands."

An ancient Jewish historian named Josephus wrote that "Hyksos" meant "shepherd kings." He thought this because he believed the Hyksos were connected to the Jews. However, this translation is likely incorrect. Other ancient writers, like Eusebius, gave the correct meaning of "foreign kings."

How the Name Was Used

Today, historians usually use the term "Hyksos" to refer specifically to the foreign kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt. It's not typically used to describe a whole group of people.

However, in ancient Egypt, the term ḥqꜣ-ḫꜣswt was also used for other foreign rulers, both before and after the Fifteenth Dynasty. For example, around 1900 BC, in the tomb of Khnumhotep II, a man named "Abisha the Hyksos" is shown. This shows the term was used for leaders from the Syro-Palestine area even earlier.

Some evidence suggests that the Hyksos kings themselves used this title. But some historians, like Kim Ryholt, argue that "Hyksos" was more of a general term for foreign rulers, not an official title used by the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty. Other experts, like Vera Müller and Manfred Bietak, disagree and believe the Hyksos did use it officially.

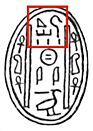

The names of Hyksos rulers in the Turin King List (an ancient list of pharaohs) are written without the royal cartouche (an oval shape around a king's name). They also have a special hieroglyph that means "foreigners." This might show that Egyptians saw them as different from their own pharaohs.

Where Did the Hyksos Come From?

Ancient Ideas

The ancient historian Josephus thought the Hyksos were connected to the Jews or Arabs. Other ancient writers said the Hyksos came from Phoenicia (a region on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea). For a long time, these were the main ideas about the Hyksos' origins.

Modern Discoveries

Since 1966, archaeologists have been digging at Tell El-Dab'a, the site of the Hyksos capital, Avaris. What they found there tells a different story. The artifacts suggest that the Hyksos came from the Levant. Their personal names show they spoke a Western Semitic language, similar to ancient Canaanites.

Kamose, the last king of the Theban Seventeenth Dynasty, called the Hyksos king Apepi a "Chieftain of Retjenu." Retjenu was an ancient name for the Levant. This also points to a Levantine background for the Hyksos.

Manfred Bietak, a leading archaeologist, found similarities in buildings, pottery, and burial customs between Avaris and sites in the northern Levant. He believes the Hyksos' "spiritual home" was in northern Syria and northern Mesopotamia.

A 2021 study of teeth from people buried at Avaris showed that both local and non-local people living there were similar. This suggests that Avaris was a busy trading center that welcomed people from many places.

History of the Hyksos

Early Connections Between Egypt and the Levant

Egyptians and Semitic people from the Levant had contact throughout Egypt's history. An early Egyptian tablet from 3000 BC shows Pharaoh Den fighting an enemy from West Asia.

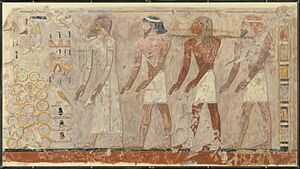

Around 1890 BC, during the reign of Senusret II, paintings in the tomb of Khnumhotep II show groups of West Asian foreigners visiting the pharaoh with gifts. These people, possibly Canaanites, are called Aamu. Their leader is named "Abisha the Hyksos," which is the first time the name "Hyksos" is known to have been used.

Soon after, a stone tablet from the time of Senusret III (1878–1839 BC) describes an Egyptian military campaign in the Levant. It mentions the capture of a foreign country called Sekmem, thought to be Shechem, and the land of "Retenu" (ancient Syria).

How the Hyksos Arrived in Egypt

The ancient historian Manetho described the Hyksos arriving as a violent invasion. He wrote that they burned cities, destroyed temples, and were very cruel to the Egyptians.

However, most modern historians disagree with this "invasion" story. They believe the Hyksos' rule began mostly peacefully. Archaeological digs show that people from Asia had been living in Avaris for over 150 years before the Hyksos kings took power. Canaanite people gradually settled there starting around 1800 BC. A study of teeth from Avaris also supports the idea of migration, not a sudden invasion. It found more non-local females than males, suggesting people moved there for reasons other than war.

Historian Manfred Bietak suggests that Egypt had always attracted people from West Asia who came looking for a better life, especially in the Delta region. Egypt relied on the Levant for shipbuilding and sailing skills. Many Asiatic immigrants worked in Egypt during the Twelfth Dynasty as soldiers, servants, and in other jobs. Avaris, being a major trade center, attracted many of these immigrants.

The Egyptian Thirteenth Dynasty became weaker around 1725 BC. Egypt then split into several smaller kingdoms, including one in Avaris ruled by the Fourteenth Dynasty. This dynasty was already mostly made up of people from West Asia. After their palace was burned, the Fourteenth Dynasty was replaced by the Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty. The Hyksos then gained control over northern Egypt.

Their Kingdom

The exact length of Hyksos rule is not fully clear. The Turin King List suggests six Hyksos kings ruled for 108 years. However, other historians have suggested different lengths, up to 180 years. The Hyksos rule happened at the same time as the Egyptian Sixteenth and Seventeenth Dynasties, a period known as the Second Intermediate Period.

The Hyksos directly controlled the eastern Nile delta. Their capital city was Avaris. Memphis might also have been an important city for them.

Other places in the Delta with many Levantine people or strong connections to the Levant included Tell Farasha, Tell el-Maghud, El-Khata'na, and Inshas. The growth of Avaris likely attracted more people from the Levant to settle in the eastern Delta.

The Hyksos claimed to rule both Lower and Upper Egypt. However, their southern border was probably around Hermopolis and Cusae. While some Hyksos objects have been found in Upper Egypt, they might be from trade, raids, or gifts, not direct rule. Most likely, the Hyksos controlled the area from Middle Egypt to southern Palestine.

Wars with the Theban Dynasty

The story of the wars between the Hyksos and the Theban Seventeenth Dynasty comes only from Egyptian sources. These sources often make the conflict sound like a fight for freedom.

Fighting seems to have started during the reign of the Theban king Seqenenra Taa. His mummy shows he was killed in battle. A later Egyptian story, The Quarrel of Apophis and Seqenenre, says the Hyksos ruler Apepi started the conflict. However, this story is likely a fictional tale, not a historical record.

About three years later, around 1542 BC, Seqenenra Taa's successor, Kamose, began a campaign against cities loyal to the Hyksos. Kamose claimed to have captured Avaris, but he returned to Thebes after catching a messenger between Apepi and the king of Kush (Nubia). Kamose likely died soon after, around 1540 BC.

Ahmose I continued the war against the Hyksos. He probably conquered Memphis, Tjaru, and Heliopolis early in his reign. Most of what we know about Ahmose I's campaigns comes from the tomb of Ahmose, son of Ebana, a soldier who fought with him. He wrote that Ahmose I attacked Avaris:

Then there was fighting in Egypt to the south of this town [Avaris], and I carried off a man as a living captive. I went down into the water—for he was captured on the city side—and crossed the water carrying him. [...] Then Avaris was despoiled, and I brought spoil from there.

Historian Thomas Schneider believes Avaris was conquered in the 18th year of Ahmose's rule. However, archaeological digs at Avaris show no widespread destruction. Instead, the city seems to have been abandoned by the Hyksos. Manetho wrote that the Hyksos were allowed to leave Egypt after making a treaty.

Although Manetho said the Hyksos were sent to the Levant, there's no archaeological proof of this. Many historians believe that many people from Asia stayed in Egypt and worked as artisans and craftsmen. Canaanite gods continued to be worshipped in Avaris.

After taking Avaris, Ahmose I also captured Sharuhen, a city in Canaan that some scholars believe was under Hyksos control.

How the Hyksos Ruled

Administration

The Hyksos rulers combined Egyptian and Levantine ways of life. They used full Egyptian royal titles and employed Egyptian scribes and officials. They also used Near Eastern ways of running their government, like having a chancellor to lead their administration.

Hyksos Rulers

The exact names, order, and length of rule for the Fifteenth Dynasty kings are not fully known. After their defeat, the Hyksos kings were not seen as true rulers of Egypt, so they were left out of most Egyptian king lists. The Turin King List mentions six Hyksos kings, but only the last one, Khamudi, has a preserved name.

The names Apepi/Apophis and Khyan appear in several sources. Scholars generally agree that Apepi and Khamudi were the last two kings of the dynasty. Apepi was a contemporary of the Theban pharaohs Kamose and Ahmose I. The order of kings is usually thought to be: Khyan, Yanassi, Apepi, Khamudi.

Recently, new archaeological finds suggest that Khyan might have ruled earlier than thought, possibly at the same time as the Thirteenth-Dynasty pharaoh Sobekhotep IV. This has led historians to rethink the entire timeline of the Hyksos period.

| Manetho | Turin King List | Genealogy of Ankhefensekhmet | Identification by Redford (1992) | Identification by Ryholt (1997) | Identification by Bietak (2012) | Identification by Schneider (2006) (reconstructed Semitic name in parentheses) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salitis/Saites (19 years) | X 15 | Schalek | Sheshi | ?Semqen (Šamuqēnu)? | ?Sakir-Har? | ? (Šarā-Dagan [Šȝrk[n]]) |

| Bnon (44 years) | X 16.... 3 years | Yaqub-Har | ?Aper-Anat ('Aper-'Anati)? | ?Meruserre Yaqub-Har? | ? (*Bin-ʿAnu) | |

| Apachnan/Pachnan (36/61 years) | X 17... 8 years 3 months | Khyan | Sakir-Har | Seuserenre Khyan | Khyan ([ʿApaq-]Hajran) | |

| Iannas/Staan (50 years) | X 18... 10 (20, 30) years | Yanassi (Yansas-X) | Khyan | Yanassi (Yansas-idn) | Yanassi (Jinaśśi’-Ad) | |

| Apophis (61/14 years) | X 19... 40 + x years | Apepi (?'A-ken?) | Apepi | Apepi | A-user-Re Apepi | Apepi (Apapi) |

| Archles/Assis (40/30 years) | identifies with ?Khamudi? | identifies with Khamudi | Identifies with Khamudi | Sakir-Har (Sikru-Haddu) | ||

| X 20 Khamudi | ?Khamudi? | Khamudi | Khamudi | not in Manetho (Halmu'di) | ||

| Sum: 259 years | Sum: 108 years |

Diplomacy and Alliances

The Hyksos were involved in diplomacy with distant lands. A clay tablet found in Avaris shows a letter written in cuneiform, a type of writing used in Mesopotamia. Gifts from the Hyksos court have also been found in Crete and the ancient Near East.

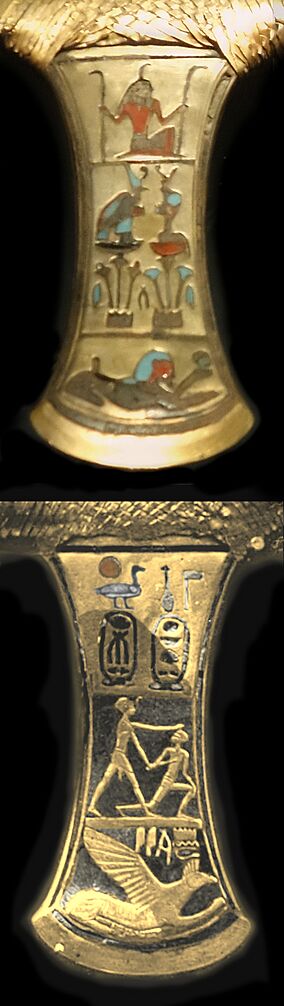

Khyan, one of the Hyksos rulers, had many contacts. Objects with his name have been found in Knossos (Crete) and Hattusha (Hittite Empire), showing diplomatic ties. A sphinx with his name was found in Baghdad, suggesting connections with Babylon.

The Theban rulers of the Seventeenth Dynasty copied the Hyksos in some ways, including their building styles and royal names. There's even evidence of friendly relations between the Hyksos and Thebes, possibly including a marriage, before the war started.

An intercepted letter between Apepi and the Nubian King of Kerma (Kush) suggests an alliance between the Hyksos and the Nubians. Many seals with the names of Asiatic rulers have been found in Kerma, showing close contact. The Nubian troops of Kerma even raided as far north as Elkab.

Hyksos Society and Culture

Royal Buildings and Art

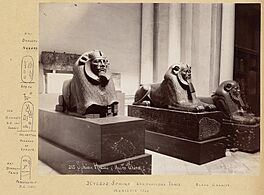

The Hyksos didn't seem to create much of their own royal art. Instead, they often reused older Egyptian statues and monuments by carving their names on them. Many of these re-carved items have the name of King Khyan.

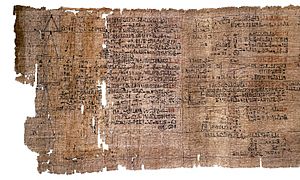

A large palace built in the Levantine style (not Egyptian) has been found in Avaris, likely built by Khyan. King Apepi supported Egyptian scribes. He ordered copies of important texts, like the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus.

The famous "Hyksos sphinxes" are statues of an earlier pharaoh, Amenemhat III. They have unusual features. The Hyksos later carved their names on these sphinxes. These sphinxes were taken by the Hyksos from other Egyptian cities and brought to Avaris to decorate their palace.

Burial Customs

The Hyksos had unique burial customs. They often buried their dead inside their settlements, unlike Egyptians who buried them outside. Some tombs had Egyptian-style chapels. They also included burials of young females, possibly sacrifices, placed in front of the tomb chamber.

The Hyksos also buried horses and other animals like donkeys. This might have been a mix of Egyptian beliefs (linking the god Set with donkeys) and Near Eastern ideas about animals showing status.

Technology

The Hyksos' horse burials suggest they brought both the horse and the chariot to Egypt. However, there's no direct evidence that the Hyksos themselves used chariots. Chariots are first mentioned in Egyptian warfare against the Hyksos at the end of their rule. It seems chariots didn't play a big role in how the Hyksos gained or lost power. Some historians also believe horse-riding might have been in Egypt even before the Hyksos.

The Hyksos are also traditionally credited with bringing other military inventions, like the sickle-sword and the composite bow. However, historians are still debating how much credit the Hyksos kingdom should get for these. They might also have introduced better ways of working with bronze. They may have worn full-body armor, which Egyptians did not use until later.

The Hyksos also introduced better weaving techniques and new musical instruments to Egypt. They also improved how wine was made.

-

The horse was probably introduced to Egypt by the Hyksos. It became a popular subject in Egyptian art, like this whip handle from the time of Amenhotep III (1390–1353 BC).

-

The two-wheeled horse chariot, seen here from the tomb of Tutankhamun, may have been introduced to Egypt by the Hyksos.

Trade and Economy

During the early Hyksos period, their capital, Avaris, became a major trade center in the Delta. The Hyksos mainly traded with Canaan and Cyprus. Trade with Canaan was very strong, with many Canaanite goods imported into Egypt. This might reflect the Hyksos' Canaanite origins. They also traded with other parts of Egypt, Nubia, and Mesopotamia. Trade with Cyprus became very important towards the end of the Hyksos period.

The Kamose stelae (stone tablets) say that the Hyksos imported "chariots and horses, ships, timber, gold, lapis lazuli, silver, turquoise, bronze, axes without number, oil, incense, fat and honey." The Hyksos also exported many items looted from southern Egypt, especially Egyptian sculptures, to Canaan and Syria. King Apepi may have been responsible for many of these transfers. The Hyksos also made their own goods, like Tell el-Yahudiyeh Ware, which had a Levantine influence.

There is little evidence of trade between Upper and Lower Egypt during the Hyksos period. Some historians believe there was a "mutual trade boycott," which might have weakened the Hyksos' economy.

Religion

Temples in Avaris were built in both Egyptian and Levantine styles. The Levantine temples were probably for Levantine gods. The Hyksos are known to have worshipped the Canaanite storm god Baal, who was linked to the Egyptian god Set. Set seems to have been the main god of Avaris even before the Hyksos. Some Hyksos artwork shows their kings in Egyptian pharaoh clothing but holding a club, which is a symbol of Baal. Although later sources claimed the Hyksos were against worshipping other gods, they did offer gifts to Egyptian gods like Ra, Hathor, Sobek, and Wadjet.

Possible Bible Connections

Ancient Historians' Views

Josephus and other ancient writers connected the Hyksos with the Jews. Josephus wrote that when the Hyksos were forced out of Egypt, they founded Jerusalem. It's not clear if this idea came from Manetho or if Josephus added it himself.

Josephus's account also links the Hyksos' expulsion to another event much later, where a group of lepers led by a priest named Osarseph were expelled from Egypt. They supposedly allied with the Hyksos and ruled Egypt for 13 years before being driven out. During this time, they were said to have oppressed Egyptians and destroyed temples. After being expelled, Osarseph supposedly changed his name to Moses. Some historians believe this second story mixes the Hyksos invasion with events from the later Amarna period.

Modern Scholarship

Most modern historians do not believe that the Egyptian stories in the Bible can be proven with historical methods. However, some scholars have tried to connect the Hyksos period to the biblical story of the Exodus.

For example, scholars like Jan Assmann and Donald Redford have suggested that the Exodus story might have been partly inspired by the Hyksos' expulsion. The Hyksos' expulsion is the only known large-scale event where people from Asia were forced out of Egypt. However, other scholars, like Manfred Bietak, point out problems with these theories. For instance, the Hyksos were a ruling elite involved in trade, while the Bible describes the Israelites as oppressed workers in Egypt.

John Bright noted that Egyptian and Biblical records show Semitic people always had access to Egypt. He suggested that Joseph, who held a high position in the Egyptian court according to the Old Testament, might have been connected to the Hyksos rule. This connection could have been easier because they shared a Semitic background. However, he also stated there is no proof for these events. Howard Vos suggested that Joseph's "coat of many colors" might be similar to the colorful clothes seen in the painting of foreigners in the tomb of Khnumhotep II.

Other scholars point out problems with connecting the Joseph story to the Hyksos period. For example, the Egyptians were said to dislike Joseph's people (shepherds), and there are many things in the story that don't fit the time period. Manfred Bietak suggests the story fits better with the later Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt. Donald Redford argues that reading the Joseph story as history is "quite wrongheaded."

Many scholars today do not believe the Exodus has any historical basis at all. The current idea among archaeologists is that if an Israelite exodus from Egypt happened, it would have been in the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt (13th century BC). The possible link between the Hyksos and the Exodus is no longer a main focus of study for historians, but it continues to be a popular idea.

Legacy of the Hyksos

Even after their defeat, the Hyksos' rule was criticized by New Kingdom pharaohs. For example, Hatshepsut, 80 years after their defeat, claimed to rebuild many shrines and temples that the Hyksos had neglected.

Ramses II later moved Egypt's capital to the Delta, building Pi-Ramesses on the site of Avaris. He set up a stone tablet there to mark the 400th anniversary of the cult of the god Set. Historians used to think this marked 400 years since the Hyksos began their rule. However, Ramses' lists of ancestors did not include the Hyksos, and there's no evidence they were honored during his reign. The Turin King List, which includes the Hyksos and other rulers not considered legitimate, seems to be from Ramses' time. The Hyksos are marked as foreign kings in this list.

Egyptian Presence in the Levant

It is often believed that Egypt created an empire in Canaan after defeating the Hyksos. Campaigns against places in Canaan and Syria were carried out by Ahmose I and Thutmose I at the start of the Eighteenth Dynasty. However, some historians, like Felix Höflmayer, argue there is little evidence for a large Egyptian empire during the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Later Stories

The New Kingdom story The Quarrel of Apophis and Seqenenre claimed that the Hyksos only worshipped the god Set. This made the conflict seem like a battle between Ra, the god of Thebes, and Set, the god of Avaris.

Manetho's description of the Hyksos, written almost 1300 years after their rule ended, was even more negative. He described them as violent conquerors. This view greatly influenced how people saw the Hyksos until modern times.

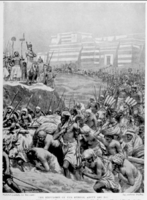

Early Modern Depictions

When the Hyksos were rediscovered in the 19th century, people developed many theories about their history and appearance. These ideas were often shown in imaginative paintings.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |