Manetho facts for kids

Manetho was an important ancient Egyptian historian and priest. He came from a city called Sebennytos. He lived around 300 BC, during the time of the Ptolemaic kings in Egypt.

Manetho wrote a famous book called Aegyptiaca, which means History of Egypt. This book is very helpful for Egyptologists. They use it to figure out the dates for events in ancient Egypt. The first time anyone mentioned Manetho's book was in a work by the Jewish historian Josephus, called "Against Apion".

Contents

What Does Manetho's Name Mean?

We don't know exactly what Manetho's name means. People have suggested a few ideas. It might mean "Gift of Thoth" or "Beloved of Thoth". Thoth was an Egyptian god of wisdom. Other ideas include "Truth of Thoth" or "Beloved of Neith". Neith was an ancient Egyptian goddess. Some also think it could mean "Horseherd" or "I have seen Thoth".

Manetho's Life and Writings

We don't know exactly when Manetho was born or when he died. His main book, Aegyptiaca, might have been written when Ptolemy I Soter (323–283 BC) or Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 BC) were ruling. Another old paper, the Hibeh Papyri, suggests he might have been writing during the time of Ptolemy III Euergetes (246–222 BC).

Manetho wrote his books in the Greek language. He also wrote other works. These include Against Herodotus, The Sacred Book, and On Festivals. He might have also written a book about astrology called the Book of Sothis.

He was probably a priest of the sun god Ra in a city called Heliopolis. He knew a lot about the worship of Sarapis. Sarapis was a god created by the Greeks and Egyptians. This worship started after Alexander the Great came to Egypt. Historians like Tacitus and Plutarch wrote that one of the Ptolemy kings brought a statue of Sarapis to Egypt.

Manetho's Aegyptiaca (History of Egypt)

The Aegyptiaca, or "History of Egypt", was probably Manetho's biggest work. It listed events in order of date. The book was split into three main parts, called volumes.

In Aegyptiaca, Manetho came up with the idea of a "dynasty". This word means a group of kings or rulers who come from the same family. He was the first person to group Egyptian rulers in this way. He started a new dynasty when there was a big change in who was in power. For example, he saw a change between the Fourth Dynasty in Memphis and the Fifth Dynasty in Elephantine. He also included many details about the kings.

Manetho might have written Aegyptiaca to be a more accurate history of Egypt than what Herodotus had written in his Histories. Manetho's other book, Against Herodotus, might have been a shorter version of Aegyptiaca. Sadly, we don't have any of the original copies of either book today.

Copies of the Book Over Time

The full Aegyptiaca book has not survived. It's very likely that other writers changed parts of it over time. They might have rewritten sections to support their own Egyptian, Jewish, or Greek histories. This makes it hard for today's historians to know how accurate the copies are.

The earliest mention of Manetho's work is in Josephus's book, Contra Apionem. This was written almost 400 years after Aegyptiaca. It seems Josephus did not have Manetho's original book. Around the same time, a shorter version of Aegyptiaca, called the Epitome, was being used. This shorter version kept Manetho's list of dynasties and some important parts. For example, it said that Menes, the first king of the First Dynasty, "was snatched and killed by a hippopotamus". We don't know if any of this short version is Manetho's original writing.

Later, writers like Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius of Caesarea made their own copies of the Epitome. Eusebius's copy was used by Jerome for a Latin translation. It was also used for an Armenian translation and by George Syncellus. Syncellus noticed that the copies by Eusebius and Africanus were very similar. So, he put them side by side in his own work.

These few copies are the only ones we have of Manetho's shorter history. Other parts of his work can be found in other old books.

Manetho used lists of kings to organize his history. Josephus wrote that Manetho also included stories, myths, and legends in his book. This was common for historians back then. Manetho likely knew about Herodotus's Greek writings. He tried to connect Egyptian history with Greek history. For example, he linked King Memnon with an Egyptian king named Amenophis. He also linked Armesis with Danaos. It's possible that later writers added these links. We do know that Manetho could write in Greek.

Ancient King Lists Manetho Might Have Used

We don't know exactly which king list Manetho used for his book. The Turin King List is the most similar one we have today. The oldest source that can be compared to Manetho's work is the Old Kingdom Annals. These date back to around 2500-2200 BC. There are also other lists like the Karnak king list, two lists at Abydos, and the Saqqara list.

The Old Kingdom Annals only exist on a stone called the Palermo Stone. There are many differences between this stone and Manetho's list. The stone stops at the fifth dynasty. It includes early kings from Lower Egypt and Upper Egypt. Manetho, however, lists several Greek and Egyptian gods as early rulers. The Annals also give yearly reports of what the kings did.

Some later king lists from the New Kingdom left out certain rulers. For example, the list made for Seti I has 76 kings. But it leaves out the Hyksos rulers and those connected to Akhenaten. The Saqqara list also leaves them out. These names were likely left out for religious reasons, not political ones. If Manetho used these lists, he couldn't have gotten all his information from them.

The Turin King List was probably a government document, not a religious one. It wouldn't have needed to leave out kings for religious reasons. Manetho, as a priest, would have had access to all kinds of written materials in the temple.

Manetho's list probably came from Lower Egypt. He included kings from the Third Intermediate Period, even those who ruled for a short time. For example, Amenemnisu (5 years) and Osochor (6 years). But he left out kings from Thebes, like Osorkon III and Pinedjem I. He also left out kings from Middle Egypt. This suggests Manetho's information came from a local temple library in the Nile Delta. The Pharaohs from Middle and Upper Egypt didn't control this part of the Delta, which is why those kings might be missing from Manetho's list.

How Kings' Names Were Recorded

By the Middle Kingdom, Egyptian kings had five different names. These included a "Horus" name, a "Two Ladies" name, and a "throne name". They also had a personal name given at birth. Some pharaohs even had more than one of these names. For example, Ramesses II used six different Horus names at different times.

We don't know if Manetho knew about all the different names for kings who lived long before him. Not all the different names for each king have been found. It's also possible kings were known by other names besides their official ones. Because Manetho translated the names into Greek, we don't know the exact original Egyptian names.

What Was Inside Aegyptiaca?

Manetho's Aegyptiaca was divided into three volumes:

Volume 1 started from the very earliest times. It listed gods and demigods as the first rulers of Egypt. Stories about gods like Isis, Osiris, Set, or Horus might have been in this part. The book then listed kings from the First Dynasty up to the Eleventh Dynasty. This covered the Old Kingdom, the First Intermediate Period, and the beginning of the Middle Kingdom.

Volume 2 covered the Twelfth Dynasty to the Nineteenth Dynasty. This included the end of the Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate Period. During this time, the Hyksos people invaded Egypt. Josephus thought the Hyksos, or "shepherd-kings", were the ancient Israelites who left Egypt. This volume also covered the start of the New Kingdom.

Volume 3 began with the Twentieth Dynasty and ended with the Thirtieth Dynasty.

Why Aegyptiaca Is Still Important Today

Even today, Egyptologists still use Manetho's way of grouping the pharaohs into dynasties. The famous French explorer and Egyptologist, Jean-François Champollion, used a copy of Manetho's lists. These lists helped him learn to read hieroglyphs, the ancient Egyptian writing. Modern histories of Egypt now use both the modern translations of names and Manetho's versions.

Images for kids

-

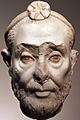

Plutarch connected Manetho with the Ptolemaic worship of Serapis. This is the head of a priest of Serapis in the Altes Museum, Berlin.

See also

In Spanish: Manetón para niños

In Spanish: Manetón para niños