Palermo Stone facts for kids

The Palermo Stone is a very old piece of stone that tells us about the kings of Ancient Egypt. It is one of seven pieces left from a much larger stone tablet called the Royal Annals of the Old Kingdom. This tablet listed all the kings of Egypt from the First Dynasty up to the early part of the Fifth Dynasty. It also recorded important events that happened each year during their rule.

Historians believe the original tablet was made around the time of the Fifth Dynasty (about 2392–2283 BCE). The Palermo Stone itself is kept in a museum in Palermo, Italy, which is how it got its name.

Sometimes, "Palermo Stone" is used to talk about all seven pieces of the Royal Annals, including those found in museums in Cairo and London. These pieces are also sometimes called the "Cairo Annals Stone." The name "Cairo Stone" can also refer only to the pieces kept in Cairo.

The Royal Annals are likely the oldest historical writings we have from Ancient Egypt. They are super important for learning about Egyptian history during the Old Kingdom period.

Contents

What the Palermo Stone Looks Like

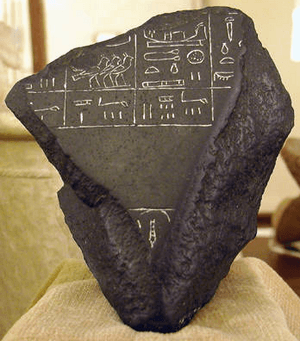

The original Royal Annals tablet, from which the Palermo Stone comes, was probably quite large. It might have been about 60 centimeters (2 feet) tall and 2.1 meters (7 feet) wide. The pieces that remain are made of a hard, black stone, likely basalt.

The Palermo Stone itself is shaped a bit like a shield. It is about 43.5 centimeters (17 inches) tall, 25 centimeters (10 inches) wide, and 6.5 centimeters (2.5 inches) thick.

The front of the stone has six lines of hieroglyphs, which are ancient Egyptian pictures used as writing.

- The first line lists the names of early kings from Lower Egypt. These kings wore the Red Crown.

- The lines that follow have parts of the royal records for pharaohs from the First to the Fourth Dynasties.

These records are lists of key events that happened each year of a king's rule. They are organized by date. The second line on the Palermo Stone starts with the last details for a king of the First Dynasty. His name is missing, but it was likely Narmer or Aha. The rest of this line shows the first nine yearly entries for the next king, probably Aha or Djer. The rest of the writing on this side continues the royal records up to the kings of the Fourth Dynasty.

The back of the Palermo Stone also has writing. This side lists events during the rule of pharaohs up to Neferirkare Kakai, who was the third ruler of the Fifth Dynasty. We don't know if the Royal Annals continued beyond this time from the pieces we have. When a king is named, the name of his mother is also written down. For example, it mentions Betrest, mother of the First Dynasty king Semerkhet, and Meresankh I, mother of the Fourth Dynasty king Seneferu.

The Royal Annals recorded many different details, such as:

- The height of the yearly Nile flood (measured by a Nilometer).

- Details about festivals, like the Sed festival.

- Information about taxes.

- Records of sculpture and buildings.

- Notes about warfare.

How the Palermo Stone Was Found

We don't know exactly where the original large stone tablet came from. None of the seven pieces have a clear history of where they were dug up. One piece in Cairo is said to have come from an ancient site called Memphis. Three other pieces in Cairo were reportedly found in Middle Egypt. No one has ever said where the Palermo Stone itself was found.

A lawyer from Sicily, Ferdinand Guidano, bought the Palermo Stone in 1859. It has been in Palermo since 1866. In 1877, the Guidano family gave it to the Palermo Archaeological Museum.

There are five pieces of the Royal Annals in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Four of these were added to the museum between 1895 and 1914. The fifth piece was bought in 1963. One small piece is in the Petrie Museum in London. It is part of the collection of the famous archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie.

In 1895, a French archaeologist visited Palermo and realized how important the stone was. The writing on the stone was translated in 1902 by Heinrich Schäfer.

Things We Don't Know For Sure

There are some debates among historians about the Palermo Stone and the Royal Annals.

- Historians are not sure if the writing was all done at once or if it was added to over many years.

- There is also no full agreement on when the writing was actually made. Was it written soon after the events happened, or much later? Some think it might have been made much later, perhaps during the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (747-656 BCE). However, most details suggest that even if it was copied later, it was based on a very old original from the Old Kingdom.

- People also wonder if all the pieces we have truly belong to the same original stone tablet or if they come from different copies. Some have even suggested that certain pieces in Cairo might not be real.

The writing on the stone is hard to read. This is because some parts are damaged, and also because it is extremely old. If the writing is a later copy, there's also a chance that mistakes were made when it was copied.

Why the Palermo Stone is Important

The Palermo Stone and the other pieces of the Royal Annals are incredibly important for understanding the history of the Old Kingdom. For example, they list the names of royal family members during the first five dynasties that are not found anywhere else.

Later Egyptian king lists, like the Turin Canon (from the 13th century BCE) and the Abydos king list (from the time of Seti I, 1294–1279 BCE), say that Menes (who was probably Narmer) was the first king of the First Dynasty. They say he was the one who united Egypt. However, the top line of the Royal Annals names some earlier rulers of Upper and Lower Egypt. These rulers must have lived before Egypt was united. Historians are still discussing how to connect these names to real historical people.

The ancient historian Manetho probably used something like the Royal Annals tablet to write his history of Egypt's early dynasties. He wrote this history in the third century BCE. The king list that best matches his work is the Turin Canon.

See also

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Piedra de Palermo para niños

In Spanish: Piedra de Palermo para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |