Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan facts for kids

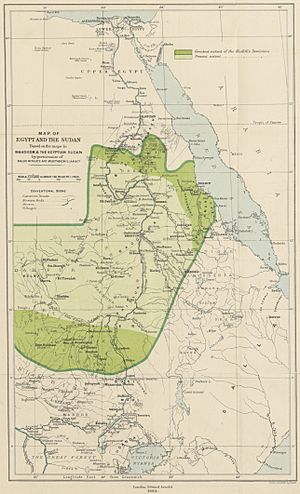

The Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan was a military campaign between 1896 and 1899. It was led by Britain and Egypt to take back control of Sudan. This land had been lost by Egypt between 1884 and 1885 during the Mahdist War. After a big defeat at Khartoum, Egypt only held onto Suakin and Equatoria. The conquest from 1896 to 1899 defeated the Mahdist State. It brought back Anglo-Egyptian rule, which lasted until Sudan became independent in 1956.

Contents

Why the Conquest Happened

Many people in Britain wanted to take back Sudan after 1885. They especially wanted to "avenge Gordon", a British general who had been killed. However, Lord Cromer, the top British official in Egypt, thought Egypt needed to get its money in order first. He believed Sudan was important, but not worth making Egypt go bankrupt.

By 1896, British Prime Minister Salisbury saw that other countries like France, Italy, and Germany were interested in Sudan. He knew that only by taking back control could Britain and Egypt stop these other powers. Also, Italy had just lost a big battle to Ethiopia in March 1896. This made Italy ask Britain for help to stop Mahdist forces from attacking their soldiers.

On March 12, Britain decided to advance towards Dongola. This was partly to help Italy. Britain also wanted to stop France, which had sent an explorer to claim part of Sudan for France. This made Britain decide to fully defeat the Mahdist State and bring back Anglo-Egyptian rule.

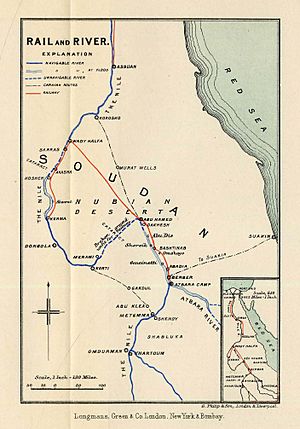

Lord Salisbury then ordered Brigadier Herbert Kitchener to prepare for an advance up the Nile River. Kitchener had never led a large army in battle before. He planned his attack carefully. In the first year, he aimed to take back Dongola. In the second, he would build a new railway. In the third, he would retake Khartoum.

Kitchener's Army

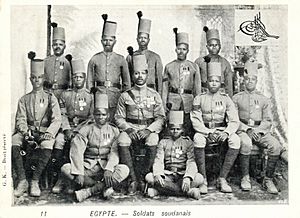

The Egyptian army got ready. By June 4, 1896, Kitchener had about 9,000 soldiers. This included ten infantry battalions, fifteen cavalry and camel corps squadrons, and three artillery batteries. Most of the soldiers were Sudanese or Egyptian. Only a few hundred British soldiers and some Maxim gunners were part of the force.

Kitchener used as many Sudanese troops as possible. They were cheaper and could handle the harsh conditions in Sudan better than Europeans. To get more Sudanese soldiers for the invasion, the Sudanese troops guarding Suakin on the Red Sea were moved. Indian soldiers replaced them in Suakin.

The Sudan Military Railway

Kitchener believed that good transport and communication were very important. In 1885, relying on the river and its changing water levels had caused problems for a previous British expedition. Kitchener wanted to avoid this. So, he decided to build new railways to support his army.

The first railway was built along the Nile to a supply base at Akasha. Then it went south towards Kerma. This railway helped supplies reach Dongola all year round, even when the Nile was not flooded. The railway reached Akasha by June 26 and Kosheh by August 4, 1896.

A dockyard was also built. Three new, larger gunboats were brought in pieces by rail. They were then put together on the river. Each gunboat had a 12-pounder gun, two 6-pounders, and four Maxim guns. In August 1896, a storm washed away 12 miles of the railway. Kitchener personally oversaw 5,000 men who worked day and night to rebuild it in just one week. After Dongola was captured, this line was extended south to Kerma.

Building the 225-mile railway from Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamad was a much bigger challenge. Many thought it was impossible. But Kitchener hired Percy Girouard, who had worked on the Canadian Pacific Railway. Work started on January 1, 1897. It picked up speed after the Kerma line was finished in May. By July 23, 103 miles were laid. However, Mahdist forces from Abu Hamad kept attacking the project.

Kitchener ordered General Archibald Hunter to advance and deal with this threat. Hunter's forces traveled 146 miles in eight days and captured Abu Hamad on August 7, 1897. The railway then reached Abu Hamad on October 31.

Building a railway in a waterless desert was very difficult. But Kitchener was lucky to find two water sources and had wells dug. To save money, he used old materials from a railway built in the 1870s. He also borrowed steam engines from South Africa. Kitchener's workers were soldiers and convicts. He pushed them very hard, often working himself and sleeping only four hours a night. As the railway progressed, many men died due to the harsh desert conditions.

The Sudan Military Railway was later called the deadliest weapon against the Mahdist forces. The 230 miles of railway cut the travel time between Wadi Halfa and Abu Hamad from 18 days by camel and steamer to just 24 hours by train. This was possible all year round. Kitchener also laid 630 miles of telegraph cable and built 19 telegraph offices. These offices soon handled hundreds of messages daily.

Later, when the line was extended towards Atbara, Kitchener could transport three heavily armed gunboats in sections. These were put back together at Abadieh. This allowed him to patrol the river up to the sixth cataract.

Campaign of 1896

The Egyptian army quickly moved to the border at Wadi Halfa. On March 18, they began moving south to take Akasha. This village was meant to be the main base for the expedition. Akasha was empty when they arrived on March 20. Kitchener spent the next two months building up his forces and supplies.

The first serious fight with Mahdist forces happened in early June at Farka. This village was a strong Mahdist position. Its commanders, Hammuda and Osman Azraq, had about 3,000 soldiers. They decided to stand their ground. At dawn on June 7, two Egyptian columns attacked the village from the north and south. They killed 800 Mahdist soldiers. Others jumped into the Nile to escape. This cleared the way to Dongola. But Kitchener stuck to his careful and prepared approach.

Kitchener took time to gather supplies at Kosheh. He also brought his gunboats south through the second cataract of the Nile. This was to prepare for an attack on Dongola. The Egyptian river navy included gunboats like Tamai and El Teb. They had to wait for the Nile to flood before they could pass over the second cataract. In 1896, the flood was very late. The first boat could not pass until August 14. Each of the seven boats had to be pulled over the cataract by two thousand men. This took one day per boat. Three new gunboats, brought by rail and assembled at Kosheh, joined this force.

Dongola was defended by a large Mahdist force led by Wad Bishara. It included 900 jihadiyya (fighters), 800 Baqqara Arabs, 2,800 spearmen, and over 1,000 camel and horse cavalry. Kitchener could not advance on Dongola right after the Battle of Farka. A disease called cholera broke out in the Egyptian camp. It killed over 900 men in July and early August 1896.

With the summer of 1896 bringing disease and bad weather, Kitchener's forces, supported by gunboats, finally began to move up the Nile towards Kerma. Wad Bishara had set up a position there. But instead of defending it, he moved his forces across the river. This way, he could fire heavily on the Egyptian gunboats as they came upstream.

On September 19, the gunboats attacked the Mahdist positions several times. But the Mahdist fire was too strong. Kitchener ordered his boats to simply steam past the Mahdist position towards Dongola. Seeing this, Wad Bishara pulled his forces back to Dongola. On September 20, the gunboats exchanged fire with the town's defenders. On September 23, Kitchener's main army reached the town. Wad Bishara saw the huge Egyptian force and had been weakened by days of gunboat attacks. He withdrew. The town was captured, as were Merowe and Korti. The Egyptian army lost only one soldier killed and 25 wounded in the capture of Dongola. Kitchener was promoted to Major-General.

Campaign of 1897

The fall of Dongola surprised the Khalifa and his followers in Omdurman. Their capital was now directly threatened. They thought Kitchener might attack by crossing the desert from Korti to Metemma, as a previous British expedition had done. So, the Khalifa ordered his commanders to bring their forces to Omdurman. This strengthened its defenses with about 150,000 extra fighters. This gathered the Mahdist forces in the capital and the areas leading to it along the Nile.

The Khalifa knew Kitchener had a strong river force that had passed the second cataract. He tried to stop it from going further upriver by blocking the sixth cataract at the Shabluka gorge. This was the last river obstacle before Omdurman. Forts were built at the gorge, and the paddle-steamer Bordein carried guns and supplies upriver.

Kitchener did not advance on Omdurman right after taking Dongola. By May 1897, the Khalifa's forces had grown. He felt strong enough to take a more aggressive approach. He decided to move his Kordofan army down the river to Metemma. The people of Metemma, the Ja'alin, were becoming less loyal to the Mahdist state as the Egyptian army advanced. Their chief, Abdallah wad Saad, wrote to Kitchener on June 24. He promised his people's loyalty to Egypt and asked for help against the Khalifa. Kitchener sent 1,100 rifles and ammunition. But they did not arrive in time. The Khalifa's army reached Metemma on June 30, attacked the town, killed wad Saad, and drove away his followers.

For Kitchener, much of 1897 was spent extending the railway to Abu Hamed. The town was captured on August 7, and the railway reached it on October 31. Even before this strongpoint was secured, Kitchener ordered his gunboats to go upriver past the fourth cataract. With help from the local Shayqiyya people, the attempt began on August 4. The current was so strong that the gunboat El Teb could not be pulled over the rapids and sank. However, the Metemma made it safely on August 13. The Tamai followed on August 14. On August 19 and 20, the new gunboats Zafir, Fateh, and Nasir also passed the cataract.

The sudden advance of the river force and uncertainty about reinforcements made the Mahdist commander in Berber abandon the town on August 24. The Egyptians occupied it on September 5. The land route from Berber to Suakin was now open again. This meant the Egyptian army could get reinforcements and supplies by river, rail, and sea. As the Red Sea area returned its loyalty to Egypt, an Egyptian force also marched from Suakin to retake Kassala. Italy had temporarily held Kassala since 1893. The Italians gave control back on Christmas Day.

For the rest of the year, Kitchener extended the railway from Abu Hamad. He also built up his forces in Berber and fortified the north bank of the Atbarah River. Meanwhile, the Khalifa strengthened the defenses of Omdurman and Metemma. He also planned an attack on the Egyptian positions when the river was low. This would prevent the gunboats from moving freely.

Campaign of 1898

To ensure he had enough strength to defeat the Mahdist forces, Kitchener brought in more soldiers from the British Army. A brigade led by Major General William F. Gatacre arrived in Sudan in late January 1898. These British soldiers had to march the last thirty miles because the railway had not yet reached the front line.

Small fights happened in early spring. In March, the Mahdist forces tried to outsmart Kitchener by crossing the Atbara River. But they were outmaneuvered. The Egyptians steamed upstream and raided Shendi. Finally, at dawn on April 8, the Anglo-Egyptians launched a full attack on the forces of Osman Digna. Three infantry brigades attacked, with one held in reserve. The fighting lasted less than an hour. 81 Anglo-Egyptian soldiers were killed and 478 wounded. Over 3,000 Mahdist troops died.

The Khalifa's forces then retreated to Omdurman. They abandoned Metemma and the sixth cataract. This allowed the Egyptian army to pass without trouble. Preparations continued for an advance on Omdurman. The railway was extended south, and more reinforcements arrived. By mid-August 1898, Kitchener had 25,800 troops. This included the British Division and the Egyptian Division. The gunboat Zafir sank near Metemma on August 28. Meanwhile, the Khalifa tried to place a mine in the river to stop the Egyptian boats from attacking Omdurman. But the mine-laying ship Ismailia blew up with its own mine.

The final advance on Omdurman began on August 28, 1898.

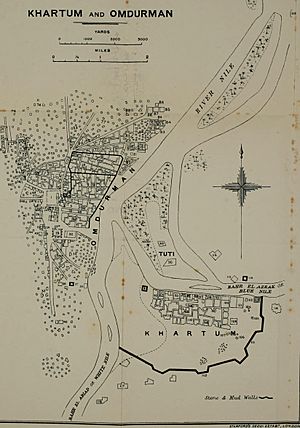

Battle of Omdurman

The defeat of the Khalifa's forces at Omdurman effectively ended the Mahdist State. Over 11,000 Mahdist fighters died at Omdurman, and another 16,000 were seriously wounded. On the British and Egyptian side, fewer than fifty soldiers died, and several hundred were wounded. The Khalifa retreated into Omdurman city but could not get his followers to defend it. Instead, they scattered and escaped. Kitchener entered the city, which surrendered without more fighting. The Khalifa escaped before he could be captured.

British gunboats attacked Omdurman before and during the battle. They damaged part of the city walls and the tomb of the Mahdi. However, the destruction was not very widespread. There was some debate about how Kitchener and his troops behaved during and after the battle. In February 1899, Kitchener denied that he had ordered or allowed his troops to kill wounded Mahdist soldiers. He also denied that Omdurman had been looted or that civilians were deliberately shot. There is no proof for the last claim. But there is some evidence for the others. Winston Churchill criticized Kitchener's actions. He privately said that the "victory at Omdurman was disgraced by the inhuman slaughter of the wounded." The Mahdi's tomb, the largest building in Omdurman, had already been looted when Kitchener ordered it to be blown up.

Final Campaigns

A force under Colonel Parsons was sent from Kassala to Al Qadarif. It was retaken from Mahdist forces on September 22. A group of two boats led by General Hunter went up the Blue Nile on September 19. Their goal was to place flags and set up small garrisons where needed. They raised the Egyptian and British flags at Er Roseires on September 30. They did the same at Sennar on their way back. Gallabat was reoccupied on December 7. However, two Ethiopian flags that had been raised there were left flying. This was done while waiting for instructions from Cairo. Even though these key towns were easily recovered, there was still much fear and confusion in the countryside. Groups of Mahdist supporters continued to roam, stealing and killing for several months after Omdurman fell. Once control was established in these areas, taking back Kordofan remained a big military challenge.

On July 12, 1898, a French explorer named Marchand reached Fashoda and raised the French flag. Kitchener quickly traveled south from Khartoum with his five gunboats. He reached Fashoda on September 18. Careful talks between both men made sure that French claims were not pushed. Anglo-Egyptian control was re-established. (See also Fashoda Incident)

On November 24, 1899, Colonel Sir Reginald Wingate trapped the Khalifa and 5,000 of his followers southwest of Kosti. In the battle that followed, the Khalifa was killed along with about 1,000 of his men. Osman Digna was captured but escaped again. (See also Battle of Umm Diwaykarat) Al Ubayyid was not taken until December 1899, by which time it had already been abandoned. In December 1899, Wingate took over from Kitchener as the leader of the army and Governor-General of Sudan. Kitchener left for South Africa.

The new Anglo-Egyptian government in Khartoum did not try to take back the far western territory of Darfur. The Egyptians had only held Darfur for a short time between 1875 and 1883. Instead, they recognized the rule of the last Sultan, Ali Dinar. They did not establish control over Darfur until 1913. (See also Anglo-Egyptian Darfur Expedition)

Osman Digna was not recaptured until 1900.

See Also

- The Mahdi

- The Khalifah

- Mahdist State

- The River War

- Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

|