Battle of Abu Hamed facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Abu Hamed |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mahdist War | |||||||

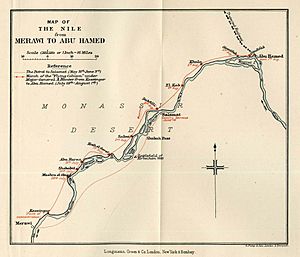

A map from Winston Churchill's The River War depicting the march of General-Major Hunter's flying column from Merawi to Abu Hamed. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

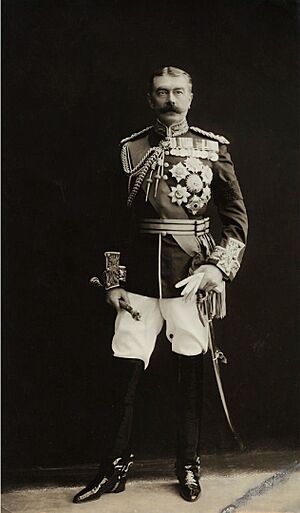

| Major-General Sir Archibald Hunter | Mohammed ZainExpression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{".Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{".Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{". | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,600 Sudanese and Egyptian soldiers | Between 400 and 1,000 Mahdist riflemen and cavalry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 23 killed 61 wounded |

250–850 killed | ||||||

The Battle of Abu Hamed happened on August 7, 1897. It was a fight between Anglo-Egyptian soldiers and Mahdist rebels. The Anglo-Egyptian forces were led by Major-General Sir Archibald Hunter. The Mahdist rebels were led by Mohammed Zain.

The Anglo-Egyptian forces won the battle. This victory gave them control of Abu Hamed. This town was very important for trade and travel across the Nubian Desert.

Abu Hamed was vital for Lord Kitchener. He was leading the Anglo-Egyptian campaign. This campaign started in March 1896. Its goal was to defeat the Mahdist state in Sudan. The Mahdists had controlled Sudan since 1881.

Kitchener wanted to build a supply railway to Abu Hamed. This railway would cross the huge Nubian Desert. It would help his forces avoid a difficult part of the Nile River. This would make it easier to reach Omdurman, the Mahdist capital. But Mahdist forces held Abu Hamed. The railway could not be built safely until they were gone.

So, Kitchener sent a special group of soldiers. This group was called a "flying column." It was led by Major-General Hunter. It had about 3,000 Egyptian soldiers. They marched quickly from Merowe to Abu Hamed. They left Merowe on July 29, 1897. After eight days, they reached Abu Hamed at dawn on August 7.

Major-General Hunter arranged his soldiers in a wide curve. This pushed the Mahdist defenders towards the river. At about 6:30 AM, Hunter ordered his troops to attack. The Mahdist riflemen were outnumbered. They were forced out of their defenses in the town. A small group of Mahdist cavalry rode away. They did not fight. They went south to report the loss. By 7:30 AM, the battle was over. Major-General Hunter sent news of the victory to Lord Kitchener.

Hunter's column lost 80 soldiers killed or wounded. The Mahdist forces lost between 250 and 850 soldiers. Mohammed Zain, the Mahdist commander, was captured. After the victory, work on the desert railway started again. The railway reached Abu Hamed on October 31. Major-General Hunter and his soldiers had stayed there. The railway solved Kitchener's biggest problem: getting supplies. It allowed his army to advance into the heart of Mahdist Sudan.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

Background of the Conflict

The Mahdist Rebellion began in 1881. A religious leader, calling himself the Mahdi, started a holy war. He fought against the Egyptian government. The British had more and more control over Egypt. This was because of the Suez Canal, built about ten years earlier.

Many people were angry about European influence. The Mahdi promised to renew the Islamic faith. He quickly gained many followers. He became a serious threat to the government. Early Egyptian attempts to stop him failed badly. The Mahdist forces, though smaller and less equipped, won. This made the Mahdi even more famous.

By 1883, the Mahdi had conquered much of Sudan. Egypt controlled Sudan at that time. The Mahdi won important battles. These victories gave him wealth and modern weapons. Colonel William Hicks, a British officer, led 8,000 Egyptian soldiers. His mission was to crush the rebellion. But Colonel Hicks and almost all his army were killed. This happened at the Battle of El Obeid.

After this defeat, Britain faced money problems in Egypt. They decided not to fight more. Instead, they chose General Charles George Gordon. He was to lead the evacuation of civilians and equipment from Sudan. Gordon worked from Khartoum. He helped many loyal civilians leave Sudan. But he refused to leave Khartoum himself. He kept a small force there. He decided to fight the Mahdi.

Mahdist forces then surrounded Khartoum in March 1884. The city was cut off. Gordon had to surrender or be defeated. After a long delay, the British government sent help. Sir Garnet Wolseley led this relief group. They quickly followed the Nile to Khartoum. But Wolseley's group arrived on January 28, 1885. This was two days after Khartoum had fallen. General Charles Gordon was killed.

The Mahdi died less than six months later. But he had already set up his Islamic state in Sudan. He moved its capital to Omdurman. A leader called the Khalifa took over after the Mahdi died. He kept the state strong through his rule.

Kitchener's Plan

Britain and Egypt did not try to intervene again until 1896. Several things made the British government act. Egypt's economy had improved. People in Britain wanted revenge for General Gordon's death. Also, France, Britain's rival, was moving into the Nile river valley. Belgians were also a concern. Finally, Britain wanted to distract the Khalifa. This would help the Italians in Eritrea. They were weak after a recent defeat by Menelik II, Emperor of Ethiopia.

The government chose Herbert Horatio Kitchener to lead the new mission. He was given about 10,000 soldiers. He also had Britain's newest technology. This included Maxim guns, heavy artillery, and small gunboats.

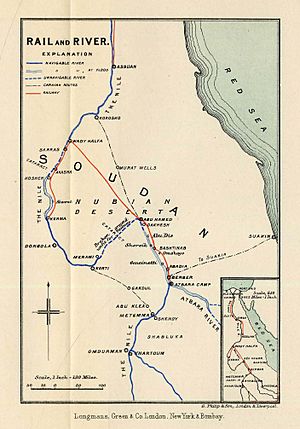

Kitchener's mission started in March 1896. They left Egypt and entered Mahdist Sudan that month. His soldiers moved along the Nile. They used the river for supplies and communication. They also built railway tracks around parts of the river that boats could not pass.

But they could not use this method all the way to Omdurman. The Nile goes far south to Ed Debba. Then it turns sharply north-east to Abu Hamed. From there, it turns south again. The part of the river from Merowe to Abu Hamed has many cataracts. These are rocky, unnavigable sections. The land along the banks was also not good for railroads. This made the journey very hard and slow.

Kitchener looked for another way. He decided to build a railway across the vast, dry Nubian Desert. This was thought to be impossible. The railway would connect Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamed. Abu Hamed was a small town controlled by the Mahdists. Top engineers in Britain thought the railway was impossible. One reason was the lack of water. There were no water sources along 120 miles of the 230-mile line.

Kitchener ignored these problems. He ordered Lieutenant Percy Girouard to prepare for construction. Girouard was a skilled engineer. He surveyed the proposed route. He found that it was difficult and water was scarce. But it was possible. The decision was made in December 1896. Work on the railway officially began on January 1, 1897.

Building the railway was very hard. But steady progress was made. By July 23, 1897, the track stretched 103 miles into the desert. Here, work stopped. They feared Mahdist attacks from Abu Hamed. The railway could not continue until the town was captured. The whole campaign was waiting for the railway to be finished. Any delay could be dangerous. If the Mahdists found out Kitchener's plans, the whole operation could fail.

In May, Captain Le Gallais led a scouting mission. They checked the area around Abu Hamed. They reported that the town was not well defended. The Mahdist presence was small. But Mahdist forces had been moving. No one was sure if more soldiers were coming. Kitchener had to act fast. In late July, he chose Major-General Sir Archibald Hunter to lead the attack.

Major-General Hunter's Flying Column

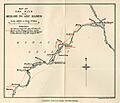

The plan was for Major-General Hunter to lead a "flying column." This was a fast-moving group of elite soldiers. They would race from Merowe north-east to Abu Hamed. Their goal was to surprise the Mahdist soldiers there. Speed was very important. Hunter's column would likely be seen by Mahdist scouts. If the scouts warned the town, Mahdist reinforcements could arrive. Then Hunter's column might be outnumbered and forced to retreat.

The soldiers chosen were among Kitchener's best. They included the 3rd Egyptian, 9th Sudanese, 10th Sudanese, and 11th Sudanese Battalions. These made up Lieutenant Hector Archibald MacDonald's brigade. Hunter's column also had an artillery battery. This included six Krupp twelve-pounders, two Maxim guns, and two older British machine guns. These were a Gardner and a Nordenfelt.

A small group of cavalry was also with the column. They had many camels for transport and supplies. The column carried food for 18 days. They also had telegraph cable. This was to keep constant communication during the 146-mile journey. In total, the force had about 3,600 soldiers.

Major-General Hunter's flying column left Kassinger on July 29 at 5:30 PM. Kassinger was a small town near Merowe. They marched only at night. This helped them avoid the hot sun and Mahdist lookouts. There was no road or path. The ground was very hard to cross. It changed between broken, rocky areas and deep sand. This made it very difficult to travel in the dark.

Hunter and Lieutenant MacDonald pushed their units hard. They wanted to arrive before Mahdist reinforcements. The column marched until midnight, covering over 16 miles. Sleeping during the day was impossible due to the heat. The tired men could only rest when they found enough shade in the desert.

The march continued this way. On August 4, they reached the village of El Kab. A shot fired at the column showed that the Mahdists knew they were there. Major-General Hunter knew reinforcements would be heading to Abu Hamed. He increased his column's speed even more. Three soldiers from the 3rd Egyptian Battalion died. Fifty-eight others fell behind. On August 5, 150 friendly Ababdeh joined Hunter's forces at Kuli.

On the night of August 6, the column marched another 16 miles. The ground was extremely difficult. They reached Ginnifab, just two miles from Abu Hamed. Here, half of the 3rd Egyptian Battalion left the column. They guarded the supply train and reserve ammunition. After a two-hour rest, Major-General Hunter ordered his men to prepare. The final attack began.

The Battle

Abu Hamed was a small town. It had many houses and narrow alleyways. It was on the bank of the Nile river. A slightly raised plateau surrounded it on three sides. Three stone watchtowers stood nearby. Mahdist lookouts in these towers saw Major-General Hunter's force coming.

Reinforcements from Berber had not arrived in time. But the town's commander, Mohammed Zain, refused to run away. The Mahdist soldiers quickly took up defensive positions. Riflemen stood in trenches in front of the town. Soldiers with close-combat weapons were inside houses and in the streets. A small group of cavalry waited, ready to act. In total, the defense had between 400 and 1,000 soldiers.

Hunter's force moved towards the town in a semi-circle shape. The four battalions were arranged from left to right: 10th Sudanese, 9th Sudanese, the smaller 3rd Egyptian, and 11th Sudanese. The artillery battery was with the 3rd Egyptian.

They reached the top of the plateau overlooking the town. It was about 300 yards away. This was at 6:15 AM. Major-General Hunter saw that the Mahdist soldiers were ready. They were dug into their defenses. He ordered the artillery to fire at their positions. This started at 6:30 AM. But the artillery was not very effective. The guns could not hit inside the narrow trenches. They also could not break the cover where the Mahdist soldiers waited.

Hunter stopped the artillery fire. He ordered Lieutenant MacDonald to lead his brigade forward. The command to fix bayonets was given. The troops began to advance in an orderly way. They crossed the 300 yards to their target. But they faced Mahdist riflemen well-protected in their trenches. So, the soldiers in each battalion started firing without direct orders. The uncoordinated shots were somewhat effective. The Mahdist riflemen had not yet fired back.

When the battalions were about halfway across, their lines of fire started to cross. This was because of their semi-circle formation. The 10th Sudanese, on the left, had to stop. They needed to avoid being hit by the 11th Sudanese on the right.

The Mahdists in the trenches had old rifles and makeshift ammunition. They planned to wait until Hunter's forces were very close to open fire. The entrenched Mahdists endured the constant firing from the advancing forces. They waited until the distance was 100 yards. Then, the Mahdist line fired together. They hit the advancing battalions hard, especially the stopped 10th Sudanese.

Two British officers, Brevet-Major Henry Sidney and Lieutenant Edward Fitzclarence, were killed. Three Egyptian officers and a dozen regular soldiers also died. Over 50 soldiers in the brigade were wounded. After this exchange, the battalions stopped their orderly approach. They charged the trenches with their bayonets.

A fierce close-quarters fight began. Soldiers from MacDonald's brigade poured into the trenches and through the town. They fought hand-to-hand with Mahdists. This happened in the winding alleyways and narrow houses of Abu Hamed. In some places, artillery was used to dislodge strong defenders. Meanwhile, the Mahdist cavalry watched. As Hunter's battalions swept through the town, they turned and fled south towards Berber.

By 7:30 AM, Major-General Hunter's force controlled the town. Almost all the Mahdist soldiers, except the cavalry, were killed in the desperate fighting. However, a few small groups of Mahdist fighters remained. They were in fortified houses and refused to give up. Six men sent to capture a Mahdist sniper's position were killed. Hunter had to use his artillery. The building was shelled until it was ruins. But the sniper survived. Another soldier sent to find his body was shot. Finally, a second artillery barrage destroyed what was left of the structure. The rubble became silent. The sniper's body was never found. The local people had armed themselves with clubs and spears. They tried to defend themselves during the battle. But they did not play a big part in the outcome.

Aftermath

The number of Mahdists killed in the battle varies in different reports. It ranges from 250 to 850. On the Anglo-Egyptian side, 23 men were killed and 61 wounded. The 10th Sudanese Battalion alone had 16 killed and 34 wounded. The Mahdist commander, Mohammed Zain, was captured and became a prisoner. Major-General Hunter captured many weapons, camels, horses, and other goods from the town.

After the battle, Lieutenant MacDonald criticized his soldiers. He was angry they had fired during their advance. He had not ordered them to do so. He thought it was a clear act of disobedience. It ruined his plan for a 150-yard bayonet charge. Brevet-Major Henry Sidney and Lieutenant Edward Fitzclarence were the only two British officers killed in the entire campaign. Lieutenant Fitzclarence was the great-grandson of King William IV. The dead soldiers from Major-General Hunter's column were buried near the town. The British officers were in decorated tombs. The other soldiers were in unmarked graves. There is a legend that the ghost of Lieutenant Sidney is guarded every night by the ghosts of his fallen battalion.

News of Major-General Hunter's victory was sent by riders and telegrams. Several sources say Kitchener himself learned of the victory. He saw the bodies of several Mahdist rebels floating down the Nile past Merowe. As soon as he heard the news, work on the desert railway started again. Construction moved quickly. The railway reached Abu Hamed by October 31, 1897.

The success of the desert railway was extremely important for Kitchener's campaign. His army's advance towards the Mahdist capital depended entirely on the trains. These trains brought water, supplies, and reinforcements every day. Capturing Abu Hamed allowed this railway to be completed across the difficult Nubian Desert. This made Kitchener's approach possible.

When Major-General Hunter captured Abu Hamed, Mahdist reinforcements were less than 20 miles away. Hunter knew they had been racing towards the town since his force was spotted on August 4. Hunter was low on supplies. His men were very tired. He doubted he could hold the town if there was a counter-attack. However, the small group of Mahdist cavalry that fled the battle met the incoming Mahdist forces. They told them what happened. The incoming forces immediately turned south, away from Abu Hamed.

The Mahdist commander at Berber heard about the battle on August 9. He faced incoming Anglo-Egyptian forces and internal conflicts. So, he decided to leave Berber in late August. Major-General Hunter then left Abu Hamed. He and his column had stayed there since the battle. He moved south to occupy Berber. This helped the campaign advance further.

Images for kids

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |