William IV facts for kids

Quick facts for kids William IV |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by Martin Archer Shee, 1833

|

|||||

| King of the United Kingdom (more...) | |||||

| Reign | 26 June 1830 – 20 June 1837 | ||||

| Coronation | 8 September 1831 | ||||

| Predecessor | George IV | ||||

| Successor | Victoria | ||||

| King of Hanover | |||||

| Reign | 26 June 1830 – 20 June 1837 | ||||

| Predecessor | George IV | ||||

| Successor | Ernest Augustus | ||||

| Born | 21 August 1765 Buckingham House, London, England |

||||

| Died | 20 June 1837 (aged 71) Windsor Castle, Berkshire, England |

||||

| Burial | 8 July 1837 Royal Vault, St George's Chapel, Windsor |

||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue more... |

|

||||

|

|||||

| House | Hanover | ||||

| Father | George III | ||||

| Mother | Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz | ||||

| Religion | Protestant | ||||

| Signature |  |

||||

| Military career | |||||

| Allegiance | Great Britain | ||||

| Service/ |

Royal Navy | ||||

| Years of active service | 1779–1790 | ||||

| Rank | Rear-Admiral (active service) | ||||

| Commands held |

|

||||

| Battles/wars | Battle of Cape St. Vincent | ||||

William IV (born William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover. He ruled from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837.

William was the third son of George III. He became king after his older brother, George IV, died. William was the last king from Britain's House of Hanover.

In his younger years, William served in the Royal Navy. He spent time in British North America and the Caribbean. This led to his nickname, the "Sailor King". In 1789, he was given the title Duke of Clarence and St Andrews. Later, in 1827, he became Britain's first Lord High Admiral since 1709.

William became king at 64 years old because his two older brothers had no children who could legally inherit the throne. His time as king saw many important changes. These included updates to the English Poor Laws, rules to limit child labour, and the end of slavery in most of the British Empire. The way people voted was also changed by the Reform Acts of 1832.

William did not get involved in politics as much as his father or brother. However, he was the last British king to choose a prime minister against the wishes of Parliament. He also gave his German kingdom, Hanover, a new, more liberal constitution, which did not last long.

When William died, he had no surviving children who could legally inherit the throne. However, he had ten children with actress Dorothea Jordan; eight of them were still alive when he died. Later in his life, he married Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen. He was succeeded by his niece, Queen Victoria, in the United Kingdom. His brother, Ernest Augustus, became King of Hanover.

Contents

William was born on 21 August 1765 at Buckingham House in London. He was the third child and son of King George III and Queen Charlotte. Since he had two older brothers, George and Frederick, he was not expected to become king. He was baptized on 20 September 1765 at St James's Palace.

William spent most of his early life in Richmond and at Kew Palace. He was taught by private teachers. At 13, he joined the Royal Navy as a midshipman. He was part of Admiral Digby's group of ships. For four years, his officer was Richard Goodwin Keats, who became a lifelong friend. William said he learned all his naval skills from Keats.

He was at the Battle of Cape St Vincent in 1780. His experiences in the navy were much like those of other midshipmen. He even helped with cooking and was briefly held after a small incident in Gibraltar. He was quickly released when his identity was known.

William served in New York during the American War of Independence. This made him the only member of the British royal family to visit America during the American Revolution. There was a plan to kidnap him, but British forces found out and assigned guards to William, who had been walking around New York without protection.

In 1785, William became a lieutenant. The next year, he became a captain of HMS Pegasus. In 1786, he was in the West Indies under Horatio Nelson. Nelson wrote that William was a very good officer. They were close friends and often had dinner together. William even gave away the bride at Nelson's wedding.

He was given command of HMS Andromeda in 1788. The next year, he was promoted to rear-admiral while commanding HMS Valiant.

William wanted to be made a duke like his older brothers. He also wanted more money from Parliament. His father, King George III, was not keen on this. To pressure his father, William threatened to run for a seat in the British House of Commons. King George III was worried about his son speaking to voters. So, on 16 May 1789, he made William the Duke of Clarence and St Andrews and Earl of Munster. William often sided with the Whigs, like his older brothers, who disagreed with their father's political views.

William stopped his active service in the Royal Navy in 1790. When Britain declared war on France in 1793, he wanted to serve. He hoped to be given command of a ship. However, he was not, perhaps because he had broken his arm. Later, it might have been because he spoke against the war in the House of Lords.

The next year, he spoke in favour of the war, hoping for a command, but none came. The Admiralty did not respond to his requests. He still hoped for an active role. In 1798, he was made an admiral, but this was just a title. Despite asking many times, he was never given a command during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1811, he was given the honorary title of Admiral of the Fleet.

In 1813, he came closest to fighting. He visited British troops in the Low Countries. While watching the bombing of Antwerp from a church tower, he came under fire. A bullet even went through his coat.

Instead of serving at sea, William spent time in the House of Lords. He spoke against the abolition of slavery. Slavery still existed in British colonies at that time. He argued that freedom would not help the slaves much. He had traveled widely and believed that the living standards of free people in parts of Scotland were worse than those of slaves in the West Indies. His experiences in the Caribbean made him agree with plantation owners about slavery. Some people at the time thought his views were well-argued. Others found it "shocking" that a young man would support the slave trade. In his first speech, William said that those who wanted to abolish slavery were "fanatics or hypocrites." He even insulted William Wilberforce, a leading abolitionist. On other issues, William was more open-minded. For example, he supported ending laws against non-Anglican Christians.

Family Life and Marriage

From 1791, William lived with an Irish actress named Dorothea Bland, known as Mrs. Jordan. King George III accepted his son's relationship with the actress. In 1797, he made William the Ranger of Bushy Park. This included a large home, Bushy House, for William's growing family. William lived there until he became king. His London home, Clarence House, was built between 1825 and 1827.

William and Mrs. Jordan had ten children together. Five were sons and five were daughters. Nine of them were named after William's siblings. All were given the last name "FitzClarence". Their relationship lasted for twenty years, ending in 1811. Mrs. Jordan's acting career began to decline. She went to France to avoid people she owed money to and died there in 1816.

William was deeply in debt. He tried many times to marry a rich heiress, like Catherine Tylney-Long, but he was not successful. In 1817, William's niece, Princess Charlotte of Wales, died. She was second in line to the British throne. This meant King George III had twelve children, but no grandchildren who could legally inherit the throne.

His sons, the royal dukes, then raced to marry and have an heir. William had good chances. His two older brothers had no children and were separated from their wives, who were too old to have children anyway. William was also the healthiest of the three. If he lived long enough, he would likely become king.

William's first choices for wives were either rejected by his oldest brother or turned him down. His younger brother, Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, went to Germany to find available Protestant princesses. He suggested Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel, but her father refused. Two months later, Adolphus married Augusta himself.

Finally, a princess was found who was kind and loved home life. She was happy to accept William's nine surviving children. On 11 July 1818, at Kew Palace, William married Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen.

William's marriage lasted almost twenty years until his death and was a happy one. Adelaide helped William manage his money. For their first year, they lived simply in Germany. William's debts were soon paid off, especially after Parliament gave him more money. They had two daughters, but both died very young.

Becoming Lord High Admiral

William's older brother, the Prince of Wales, had been Prince Regent since 1811. This was because their father, King George III, was mentally ill. In 1820, George III died, and the Prince Regent became King George IV. William, Duke of Clarence, was now second in line to the throne. Only his brother Frederick, Duke of York, was ahead of him.

After his marriage, William had changed. He walked for hours, ate simple meals, and mostly drank barley water. Both of his older brothers were not healthy, so it seemed likely he would become king. When Frederick died in 1827, William, then over 60, became the heir to the throne.

Later that year, the new prime minister, George Canning, made William the Lord High Admiral. This important naval role had not been held by one person since 1709. While in this job, William often argued with his Council, who were naval officers. Things got worse in 1828 when William, as Lord High Admiral, sailed off with a group of ships. He did not tell anyone where he was going and was gone for ten days. The King, George IV, asked for William's resignation through the Prime Minister, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington. William agreed to step down.

Despite these problems, William did a lot of good as Lord High Admiral. He stopped the use of the cat o' nine tails (a type of whip) for most crimes, except for mutiny. He also tried to make naval gunnery better and asked for regular reports on the condition of each ship. He ordered the first steam warship and wanted more to be built. This job allowed him to make mistakes and learn from them. This learning was very helpful before he became king.

William spent much of his remaining time during his brother's reign in the House of Lords. He supported the Catholic Emancipation Bill. His younger brother, Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, was against it. William called his brother's stance "infamous," which angered Ernest.

George IV's health was getting worse. By early 1830, it was clear he was dying. The King said goodbye to William at the end of May. He told William, "God's will be done. I have injured no man. It will all rest on you then." William truly cared for his older brother, but he also felt excited about becoming king soon.

William IV's Reign

Becoming King and Early Popularity

When George IV died on 26 June 1830, William became King William IV. He was 64 years old, making him the oldest person to become a British monarch until Charles III in 2022.

Unlike his brother, who loved grand ceremonies, William was humble. He did not like a lot of pomp and show. George IV often stayed at Windsor Castle. But William, especially early in his reign, was known to walk alone through London or Brighton. He was very popular with the people, who saw him as more friendly and down-to-earth than his brother. This popularity lasted until the Reform Crisis.

The King quickly showed he was a hard worker. The Prime Minister, Wellington, said he got more done with King William in ten minutes than with George IV in many days. Lord Brougham said William was excellent at business. He asked enough questions to understand things. George IV was afraid to ask questions, and George III asked too many and did not wait for answers.

The King tried his best to be liked by the people. Charlotte Williams-Wynn wrote that the King was working hard to be popular. Emily Eden noted that he was a great improvement over the previous king. She said William "wishes to make everybody happy."

William fired his brother's French chefs and German band. He replaced them with English ones, which the public liked. He gave many of George IV's art pieces to the nation. He also cut the royal horse stud in half. George had started expensive renovations on Buckingham Palace. William refused to live there. He even tried twice to give the palace away. Once he offered it to the Army as barracks, and another time to Parliament after the Houses of Parliament burned down in 1834.

His informal style could be surprising. When at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, King William would ask hotels for their guest lists. He would then invite anyone he knew to dinner. He told guests not to "bother about clothes."

When he became king, William did not forget his nine surviving children. He made his oldest son, George, the Earl of Munster. He gave his other children high social standing. However, his children often asked for more money and titles. This annoyed the press, who called them "impudent and greedy." William's relationship with his sons had many "painful quarrels" over money and honours. His daughters, however, were a joy to his court. They were "pretty and lively" and made society more fun.

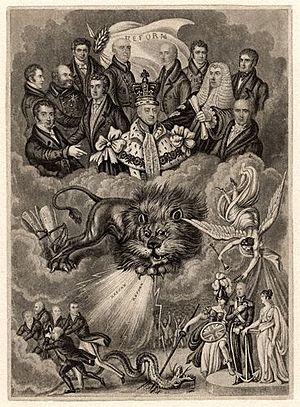

The Reform Crisis of 1832

When a monarch died, new elections were required. In the 1830 election, Wellington's Tories lost ground to the Whigs, led by Lord Grey. The Tories still had the most seats, but they were divided. Wellington was defeated in the House of Commons in November, and Lord Grey formed a new government.

Grey promised to reform the voting system. It had not changed much since the 1400s. There were many unfair parts. For example, large cities like Manchester and Birmingham had no Members of Parliament (MPs). But small towns, called rotten or pocket boroughs, like Old Sarum with only seven voters, elected two MPs each. Often, rich aristocrats controlled these rotten boroughs. Their chosen candidates were always elected by their tenants, especially since voting was not secret yet. Landowners could even sell these seats to people who wanted to become MPs.

In 1831, the First Reform Bill was defeated in the House of Commons. Grey's government asked William to dissolve Parliament, which would lead to a new election. At first, William was unsure. Elections had just happened the year before, and the country was very excited, which could lead to violence. However, he was annoyed by the Opposition. They planned to pass a resolution in the House of Lords against dissolving Parliament.

William saw this as an attack on his power. At the strong request of Lord Grey and his ministers, the King decided to go to the House of Lords himself to stop Parliament. The monarch's arrival would stop all debate and prevent the resolution from passing. When told his horses could not be ready quickly, William supposedly said, "Then I will go in a hackney cab!"

His coach and horses were quickly prepared, and he went straight to Parliament. The Times newspaper described the scene before William arrived: "It is utterly impossible to describe the scene... The violent tones and gestures of noble Lords... astonished the spectators." Lord Londonderry even waved a whip, threatening government supporters, and had to be held back. William quickly put on his crown, entered the Chamber, and dissolved Parliament.

This forced new elections for the House of Commons. The reformers won a great victory. But even though the Commons wanted reform, the House of Lords was still strongly against it.

The crisis paused briefly for the King's coronation on 8 September 1831. William first wanted to skip the coronation entirely. He felt that wearing the crown to stop Parliament was enough. But traditionalists convinced him otherwise. However, he refused to have an expensive coronation like his brother's. The 1821 coronation had cost £240,000. William ordered his coronation to cost less than £30,000. When traditional Tories threatened to boycott it, calling it the "Half Crown-nation," the King replied that they should go ahead. He said he expected "greater convenience of room and less heat."

After the House of Lords rejected the Second Reform Bill in October 1831, calls for reform grew across the country. Protests became violent in what were called "Reform Riots." Despite the Lords' stubbornness, the Grey government refused to give up and brought the Bill back.

Frustrated, Grey suggested that the King create enough new peers (members of the House of Lords) to pass the Bill. The King did not like this idea. He had already created 22 new peers for his Coronation Honours. William reluctantly agreed to create enough peers to "secure the success of the bill." However, he told Grey that the new peerages should be limited to the eldest sons or other heirs of existing peers. This way, the new titles would eventually merge with older ones.

This time, the Lords did not reject the bill completely. Instead, they started to change its main points through amendments. Grey and his ministers decided to resign if the King did not agree to create many new peers right away to pass the bill as it was. The King refused and accepted their resignations.

The King tried to bring the Duke of Wellington back into power. But Wellington did not have enough support to form a government. The King's popularity dropped very low. Mud was thrown at his carriage, and people booed him in public. The King then agreed to bring Grey's government back. He also agreed to create new peers if the House of Lords continued to cause problems.

Worried by the threat of new peer creations, most of the bill's opponents did not vote. The 1832 Reform Act was then passed. The public blamed William's actions on his wife and brother. His popularity soon recovered.

Foreign Policy and Hanover

William did not trust foreigners, especially the French. He admitted this was a "prejudice." He also strongly believed that Britain should not get involved in other countries' internal affairs. This caused problems with his Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, who wanted to intervene more.

William supported Belgian independence. After some unsuitable candidates were suggested, he favored Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Leopold was the widower of William's niece, Charlotte. He became a candidate for the new Belgian throne.

Though he was sometimes seen as clumsy, William could be smart and diplomatic. He predicted that building a canal at Suez would make good relations with Egypt very important for Britain. Later in his reign, he praised the American ambassador at a dinner. He said he regretted not being "born a free, independent American." He respected that nation for giving birth to George Washington, whom he called "the greatest man that ever lived." By using his personal charm, William helped improve relations between Britain and America, which had been damaged during his father's reign.

In Germany, people thought Britain controlled Hanoverian policy, but this was not true. In 1832, Austrian leader Klemens von Metternich introduced laws to stop new liberal movements in Germany. Lord Palmerston was against this. He wanted William to influence the Hanoverian government to take the same stance. However, the Hanoverian government agreed with Metternich, much to Palmerston's dismay. William refused to interfere.

The disagreement between William and Palmerston over Hanover continued the next year. Metternich called a meeting of German states in Vienna. Palmerston wanted Hanover to decline the invitation. Instead, William's brother, Prince Adolphus, who was Viceroy of Hanover, accepted. William fully supported this. In 1833, William signed a new constitution for Hanover. This constitution gave more power to the middle class, some power to the lower classes, and expanded the role of the parliament. This constitution was later cancelled by his brother and successor in Hanover, King Ernest Augustus.

Later Reign and Death

For the rest of his reign, William only actively interfered in politics once. This was in 1834. He became the last British king to choose a prime minister against the wishes of Parliament. In 1834, the government was becoming unpopular. Lord Grey retired, and Lord Melbourne became Prime Minister. Melbourne kept most of the previous ministers, and his government had a large majority in the House of Commons.

However, some government members were disliked by the King. He was also worried by their increasingly left-wing policies. The year before, Grey had passed a law reforming the Protestant Church of Ireland. This Church collected tithes (taxes) throughout Ireland and was very wealthy. But only about one-eighth of the Irish people belonged to the Church of Ireland. In some areas, there were no Church of Ireland members at all. Yet, a priest was still paid by tithes collected from local Catholics and Presbyterians. This led to complaints that lazy priests lived in luxury at the expense of poor Irish people. Grey's law had cut the number of bishops in half, removed some unnecessary jobs, and changed the tithe system. More radical members of the government, including Lord John Russell, suggested taking the extra money from the Church of Ireland. The King especially disliked Russell, calling him "a dangerous little Radical."

In November 1834, Lord Althorp, who was the leader of the House of Commons and Chancellor of the Exchequer, inherited a noble title. This moved him from the Commons to the Lords. Melbourne had to choose a new Commons leader and a new Chancellor. The only person Melbourne thought suitable was Lord John Russell. But William (and many others) found Russell unacceptable because of his radical political ideas.

William claimed the government was too weak to continue. He used Lord Althorp's move to the Lords as an excuse to dismiss the entire government. With Lord Melbourne gone, William chose a Tory, Sir Robert Peel, to lead. Since Peel was in Italy, the Duke of Wellington was temporarily made Prime Minister. When Peel returned and took over, he realized he could not govern because the Whigs had a majority in the House of Commons. So, Parliament was dissolved for new elections. Although the Tories won more seats than in the previous election, they were still a minority. Peel stayed in office for a few months but resigned after several defeats in Parliament. Melbourne was then restored as Prime Minister and remained so for the rest of William's reign. The King was forced to accept Russell as the Commons leader.

The King had a mixed relationship with Lord Melbourne. Melbourne's government suggested more democratic ideas. For example, giving more power to the Legislative Council of Lower Canada. This worried the King greatly, as he feared it would lead to losing the colony. At first, the King strongly opposed these ideas. William told Lord Gosford, who was going to be Governor General of Canada: "Mind what you are about in Canada... the Cabinet is not my Cabinet; they had better take care or by God, I will have them impeached."

When William's son Augustus asked if the King would host dinners during Ascot week, William sadly replied, "I cannot give any dinners without inviting the ministers, and I would rather see the devil than any one of them in my house." Despite his feelings, William approved the government's reform plans. The King and Prime Minister eventually found a way to work together. Melbourne used tact and firmness, and William realized his prime minister was not as radical as he had feared.

Both the King and Queen were fond of their niece, Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent. They tried to build a close relationship with her. However, this was difficult because of the conflict between the King and Victoria's widowed mother, the Duchess of Kent and Strathearn. The King was angry because he felt the Duchess disrespected his wife. At his last birthday dinner in August 1836, William used the chance to speak his mind. With the Duchess and Princess Victoria present, William said he hoped to live until Victoria was 18. This way, the Duchess would never be regent (ruler in Victoria's place). He said he trusted "that my life may be spared for nine months longer... I should then have the satisfaction of leaving the exercise of the Royal authority to the personal authority of that young lady... and not in the hands of a person now near me, who is surrounded by evil advisers and is herself incompetent to act with propriety." This speech was so shocking that Victoria cried, and her mother sat silently. William's outburst likely contributed to Victoria's view of him as "a good old man, though eccentric and singular." William lived, though very ill, until the month after Victoria turned 18. "Poor old man!" Victoria wrote as he was dying, "I feel sorry for him; he was always personally kind to me."

William was deeply affected by the death of his eldest daughter, Sophia, Lady de L'Isle and Dudley, in April 1837. She died during childbirth. William and his eldest son, the Earl of Munster, were not speaking at the time. William hoped a letter of sympathy from Munster meant they would make up. But his hopes were not met. Munster remained bitter until the end, still feeling he had not received enough money or support.

Queen Adelaide cared for William devotedly as he was dying. She did not go to bed herself for over ten days. William died early on 20 June 1837 at Windsor Castle. He was buried in the Royal Vault at St George's Chapel.

William IV's Legacy

Since William had no surviving children who could legally inherit the throne, the British crown passed to his niece, Victoria. She was the only child of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, George III's fourth son. Under Salic Law, a woman could not rule Hanover. So, the Hanoverian throne went to George III's fifth son, Ernest Augustus. William's death thus ended the personal union of Britain and Hanover, which had lasted since 1714.

The main people who benefited from William's will were his eight surviving children with Mrs. Jordan. Although William is not a direct ancestor of later British monarchs, he has many famous descendants through his children with Mrs. Jordan. These include former prime minister David Cameron, TV presenter Adam Hart-Davis, and author Duff Cooper.

William IV had a short but important reign. In Britain, the Reform Crisis showed that the House of Commons was becoming more powerful. At the same time, the House of Lords was becoming less powerful. The King's failed attempt to remove the Melbourne government showed that the monarch's political influence was decreasing.

During George III's reign, the king could dismiss a government, appoint another, dissolve Parliament, and expect voters to support the new government. This happened in 1784 and 1807. But when William dismissed the Melbourne government, the Tories under Peel failed to win the next elections. The monarch's power to influence voters and national policy had been reduced. None of William's successors have tried to remove a government or appoint one against Parliament's wishes. William understood that as a constitutional monarch, he could not act against Parliament's opinion. He said, "I have my view of things, and I tell them to my ministers. If they do not adopt them, I cannot help it. I have done my duty."

During William's reign, the British Parliament passed major reforms. These included the Factory Act of 1833 (which prevented child labour), the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (which freed slaves in the colonies), and the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 (which standardized help for the poor). William received criticism from both reformers, who felt changes did not go far enough, and from those who thought changes went too far. Some historians now see him as a capable constitutional monarch. He tried to find a middle ground between two strongly opposing groups.

Honours

British and Hanoverian Honours

- 5 April 1770: Knight of the Thistle

- 19 April 1782: Knight of the Garter

- 23 June 1789: Member of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- 2 January 1815: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- 12 August 1815: Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Hanoverian Guelphic Order

- 26 April 1827: Royal Fellow of the Royal Society

Foreign Honours

Kingdom of Prussia: 11 April 1814: Knight of the Black Eagle

Kingdom of Prussia: 11 April 1814: Knight of the Black Eagle Kingdom of France: 24 April 1814: Knight of the Holy Spirit

Kingdom of France: 24 April 1814: Knight of the Holy Spirit Russian Empire:

Russian Empire:

- 9 June 1814: Knight of St. Andrew

- 9 June 1814: Knight of St. Alexander Nevsky

Denmark: 15 July 1830: Knight of the Elephant

Denmark: 15 July 1830: Knight of the Elephant Baden:

Baden:

- 1831: Knight of the House Order of Fidelity

- 1831: Knight Grand Cross of the Zähringer Lion

Spain: 21 February 1834: Knight of the Golden Fleece

Spain: 21 February 1834: Knight of the Golden Fleece Württemberg: Knight Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown

Württemberg: Knight Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown

Issue

William had children with Dorothea Jordan and two daughters with Queen Adelaide.

| Children with Dorothea Jordan | |||

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| George FitzClarence, 1st Earl of Munster | 29 January 1794 | 20 March 1842 | Married Mary Wyndham, had children. Died aged 48. |

| Henry FitzClarence | 27 March 1795 | September 1817 | Died unmarried, aged 22. |

| Sophia FitzClarence | August 1796 | 10 April 1837 | Married Philip Sidney, 1st Baron De L'Isle and Dudley, and had children. |

| Mary FitzClarence | 19 December 1798 | 13 July 1864 | Married Charles Richard Fox, no children. |

| Lord Frederick FitzClarence | 9 December 1799 | 30 October 1854 | Married Lady Augusta Boyle, one surviving daughter. |

| Elizabeth FitzClarence | 17 January 1801 | 16 January 1856 | Married William Hay, 18th Earl of Erroll, had children. |

| Lord Adolphus FitzClarence | 18 February 1802 | 17 May 1856 | Died unmarried. |

| Augusta FitzClarence | 17 November 1803 | 8 December 1865 | Married twice, had children. |

| Lord Augustus FitzClarence | 1 March 1805 | 14 June 1854 | Married Sarah Gordon, had children. |

| Amelia FitzClarence | 21 March 1807 | 2 July 1858 | Married Lucius Cary, 10th Viscount Falkland, had one son. |

| Children with Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen | |||

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

| Princess Charlotte Augusta Louisa of Clarence | 27 March 1819 | Died a few hours after being baptized, in Hanover. | |

| Stillborn child | 5 September 1819 | Born dead at Calais or Dunkirk. | |

| Princess Elizabeth Georgiana Adelaide of Clarence | 10 December 1820 | 4 March 1821 | Born and died at St James's Palace. |

| Stillborn twin boys | 8 April 1822 | Born dead at Bushy Park. | |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Guillermo IV del Reino Unido para niños

In Spanish: Guillermo IV del Reino Unido para niños

- Cultural depictions of William IV

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |