Scapa Flow facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Scapa Flow |

|

|---|---|

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

|

|

| Location | Orkney, Scotland |

| Coordinates | 58°54′N 3°03′W / 58.900°N 3.050°W |

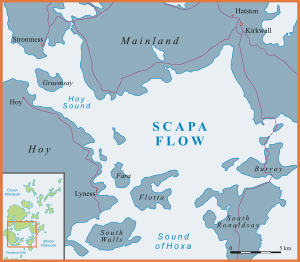

Scapa Flow is a large area of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland. It is protected by several islands, including Mainland, Graemsay, Burray, South Ronaldsay and Hoy. This sheltered bay has been very important for travel, trade, and wars for many centuries. Over a thousand years ago, Vikings used Scapa Flow to anchor their longships. It was the main naval base for the United Kingdom during both the First and Second World Wars. The base closed in 1956.

After the German fleet was sunk on purpose here after World War I, the shipwrecks became a famous place for diving. These wrecks are now home to many sea creatures.

Scapa Flow also has an oil port called the Flotta oil terminal. When the weather is good, large ships can transfer crude oil to each other here. In 2007, the world's first ship-to-ship transfer of liquefied natural gas (LNG) happened in Scapa Flow. Two ships, Excalibur and Excelsior, moved 132,000 cubic meters of LNG.

Contents

What is Scapa Flow like?

Scapa Flow has a sandy bottom that is usually about 30 meters (98 feet) deep, but it can be up to 60 meters (200 feet) deep. It is one of the world's best natural harbors and anchorages. It is big enough to hold many navies at once. The harbor covers an area of 324.5 square kilometers (125.3 square miles) and holds almost 1 billion cubic meters of water.

Why is Scapa Flow important for birds?

Scapa Flow is known as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International. This is because many birds live here, especially in winter. These include velvet scoters, horned grebes, common loons, European shags, and Eurasian curlews. Black guillemots also breed here.

A Look Back in Time: Scapa Flow's History

How did Vikings use Scapa Flow?

Stories from the 11th century, like the Orkneyinga sagas, tell us about Viking trips to Orkney.

In 1263, King Haakon IV of Norway anchored his fleet, including his large ship Kroussden, at St Margaret's Hope. He saw a sun eclipse there before sailing to the Battle of Largs. Later, on his way back to Norway, Haakon kept some of his ships in Scapa Flow for the winter. He died in December at the Bishop's Palace in Kirkwall.

By the 15th century, when Norse rule in Orkney was ending, powerful leaders called jarls controlled the islands. They had large farms near Scapa Flow to guard its entrances.

Scapa Flow during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

In 1650, during the wars of the Three Kingdoms, a Royalist general named James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose docked his ship, the Herderinnan, in Scapa Flow. He was getting ready to start a rebellion in Scotland. However, his plan failed at the Battle of Carbisdale.

Scapa Flow in the First World War

Before the 1900s, Britain's main naval bases were closer to the English Channel. This was to defend against naval powers like the Dutch, French, and Spanish.

In 1904, Germany started building up its navy, the Kaiserliche Marine. Britain decided it needed a northern base to control the North Sea. Scapa Flow had been used for British navy exercises many times before the war. So, when World War I began, it was chosen as the main base for the British Grand Fleet, even though it wasn't fortified yet.

Admiral John Rushworth Jellicoe, who led the Grand Fleet, was always worried about submarine attacks on Scapa Flow. While the fleet patrolled the west coast of Britain, Scapa Flow was made stronger. Over sixty old ships were sunk in the channels between the southern islands. These "blockships" helped to block the way and allowed the navy to use submarine nets and booms. Minefields, artillery, and concrete barriers also protected the area.

German U-boats tried to enter the harbor twice during the war, but neither attempt worked:

- In November 1914, U-18 tried to get in. A British trawler rammed it, causing a leak. The U-boat had to leave and surface, and one crew member died.

- In October 1918, UB-116 tried, but the defenses were too strong. It was found by hydrophones before it could enter. Then, shore-triggered mines destroyed it, killing all 36 sailors.

After the Battle of Jutland, the German High Seas Fleet rarely left its bases. In the last two years of the war, the British fleet was so strong that some ships moved to the dockyard at Rosyth.

The German fleet is sunk on purpose

After Germany lost the war, 74 ships of the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet were held in Scapa Flow. They were waiting for a decision about their future in the peace Treaty of Versailles.

On June 21, 1919, after seven months, German Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter decided to sink the fleet. He did this to stop the ships from falling into British hands. He thought the time for the treaty negotiations had run out, but he wasn't told that there had been a last-minute extension.

He waited for most of the British fleet to leave for exercises. Then, he gave the order to sink the ships. The Royal Navy tried hard to board the ships to stop them from sinking. But the German crews had been preparing for this order. They had welded doors open, placed explosives in weak parts of the ships, and quietly dropped important keys overboard.

The Royal Navy managed to save the battleship Baden, the light cruisers Emden, Nürnberg, and Frankfurt, and 18 destroyers. But 53 ships, most of the High Seas Fleet, were sunk. Nine German sailors died when British forces fired at them as they tried to sink their ships. These were reportedly the last deaths of the war.

Today, at least seven of the sunken German ships and some sunken British ships can be visited by divers.

Salvaging the wrecks

Many of the large ships turned upside down and settled deep in the water (25–45 meters or 82–148 feet). Some, like the battlecruiser Moltke, had parts sticking out of the water or just below the surface.

These wrecks were dangerous for ships. Small boats and fishing trawlers often got caught on them. At first, the British Admiralty said they would not try to salvage the ships. They would just let them "rest and rust." But by the early 1920s, things changed.

In 1922, the Admiralty asked companies to bid on salvaging the sunken ships. Few people thought it would be possible to raise the deeper wrecks. The contract went to Ernest Cox, a rich engineer and scrap metal dealer. He started a new company for this huge project. This began what is often called the greatest maritime salvage operation ever.

For the next eight years, Cox and his team worked to raise the sunken fleet. First, they used pontoons and floating docks to lift the smaller destroyers. These were sold for scrap to help pay for the operation. Then, they lifted the bigger battleships and battlecruisers. They sealed holes in the wrecks and welded long steel tubes to the hulls. These tubes stuck out of the water and acted as airlocks. This way, the sunken hulls became airtight. They were then raised to the surface using compressed air, still upside down.

Cox faced many challenges, including bad luck and strong storms that often ruined his work. Ships that had just been raised would sometimes sink again. During the General Strike of 1926, the salvage work almost stopped because there was no coal for the pumps and generators. Cox ordered his team to break into the fuel bunkers of the sunken battlecruiser Seydlitz to get coal. This allowed the work to continue.

Even though he lost money on the contract, Cox kept going. He used new technology and methods as needed. By 1939, Cox and the company he sold to had successfully raised 45 of the 52 sunken ships. The last one, the huge Derfflinger, was raised from a record depth of 45 meters (148 feet) just before World War II started. It was then taken to Rosyth and broken up in 1946.

A Morse key found from the battleship Grosser Kurfürst during the salvage is now in a museum in Fife.

Scapa Flow in the Second World War

Scapa Flow was chosen as the main British naval base again during the Second World War. This was mainly because it was far from German airfields.

However, the strong defenses built during the First World War had fallen apart. Protection against air attacks was not good, and the old blockships had mostly collapsed. There were anti-submarine nets, but they were weak. There were also not enough patrolling destroyers or other anti-submarine ships. Efforts to fix these problems started late and were not finished in time.

On October 14, 1939, a German U-boat, U-47, led by Günther Prien, got into Scapa Flow. It sank the battleship HMS Royal Oak, which was anchored in Scapa Bay. The U-boat fired its first torpedoes, then turned to leave. But when it saw no immediate danger, it returned for another attack. The second torpedoes made a 30-foot (9.1 m) hole in the Royal Oak. The ship quickly filled with water and turned over. Out of 1,400 crew members, 833 were lost. The wreck is now a protected war grave.

Three days later, on October 17, four Luftwaffe Junkers Ju 88 bombers attacked Scapa Flow. This was one of the first bombing attacks on Britain during the war. The attack badly damaged an old base ship, the decommissioned battleship HMS Iron Duke. It was then pulled ashore at Ore Bay. One person died and 25 were hurt. One of the bombers was shot down by British anti-aircraft guns. Three of its crew died.

New blockships were sunk, and booms and mines were placed at the main entrances. Coastal defense and anti-aircraft guns were set up. Winston Churchill ordered the building of causeways to block the eastern entrances to Scapa Flow. Italian prisoners of war built these "Churchill Barriers". They also built the Italian Chapel. These barriers now connect Mainland to Burray and South Ronaldsay by road, but they block ships from passing through. An airfield, RAF Grimsetter, was also built in 1940.

Scapa Flow Today

How is Scapa Flow used by the oil industry?

Scapa Flow is an important place for transferring and processing North Sea oil. An underwater pipeline, 30 inches (76 cm) wide and 128 miles (206 km) long, carries oil from the Piper oilfield to the Flotta oil terminal. The Claymore and Tartan oil fields also send oil to this pipeline.

What is the Scapa Flow Visitor Centre?

The Scapa Flow Visitor Centre is in Lyness on Hoy, the second largest island in Orkney. Ferries run from Houton on the Mainland from morning to evening.

The Visitor Centre is in an old naval fuel pumping station and storage tank. Next to it, you can see a round stone battery and an old artillery gun. Inside, there is a large model of the island, Scapa Flow, and the German warships.

The Scapa distillery, which makes Scotch whisky, is also located on the shore.

Scuba Diving in Scapa Flow

The wrecks of the seven remaining German ships, along with other sites like the blockships, are very popular for recreational scuba divers. They are often listed as top dive sites in the UK, Europe, and even the world. While other places have warmer water and better visibility, few offer so many large, historic wrecks close together in relatively calm diving conditions. As of 2010, at least twelve "live aboard" boats take divers to the main sites, mostly from Stromness. Diving brings a lot of business and money to the local area.

Divers need to get a permit from the Island Harbour Authorities, which can be found at diving shops. Most wrecks are 35 to 50 meters (115 to 164 feet) deep. Divers can enter the wrecks, but they are not allowed to take anything from within 100 meters (330 feet) of any wreck. However, broken pieces of pottery and glass bottles from the ships can sometimes be found in shallow waters and on beaches. The underwater visibility changes, from 2 to 20 meters (7 to 66 feet), so you can't see the whole length of most wrecks at once. But new technology now allows divers to see 3D images of them.

The important wrecks to see are:

German Battleships to Explore

The three sister battleships of the König class class: SMS König, SMS Kronprinz, and SMS Markgraf, were part of the 3rd Battleship Squadron. They fought fiercely at the Battle of Jutland in 1916. Their upside-down hulls are about 25 meters (82 feet) deep. They were never fully raised, but parts of them have been salvaged. Armor plates were blasted away, and non-ferrous metals were removed. These wrecks are highly rated dive sites because of their depth.

German Light Cruisers for Divers

The light cruisers SMS Dresden, SMS Karlsruhe, SMS Brummer, and SMS Cöln are easier for divers to reach. They lie on their sides with about 16–20 meters (52–66 feet) of water above them. Except for the shallowest, Karlsruhe, they have been salvaged less than the battleships.

Other Interesting Vessels to Dive

Other interesting dive sites include the destroyer SMS V83. This ship was raised and used by Ernest Cox during his salvage operations, then later left behind. The Churchill blockships, like the Tabarka, the Gobernador Bories, and the Doyle in Burra Sound, are also popular. You can also dive to the U-boat SM UB-116 and the trawler James Barrie. Many large parts from the ships that were raised, like the main gun turrets, fell off when the ships capsized. These still rest on the seabed near the craters made by the sunken ships.

War Grave Wrecks: Restricted Access

The wrecks of the battleships Royal Oak and Vanguard (which exploded in World War I) are war graves. They are protected sites under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986. Only divers from the British armed forces are allowed to visit these wrecks.

Legend of the Scapa Flow Curse

According to an old story, a witch once put a curse on Scapa Flow. She buried a thimble in the sand at Nether Scapa. The curse said that no more whales would be caught in the area until the thimble was found.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Scapa Flow para niños

In Spanish: Scapa Flow para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |