Scuttling of the German fleet at Scapa Flow facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Scuttling of the German fleet at Scapa Flow |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

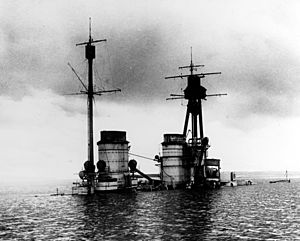

Bayern sinking by the stern |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| First Battle Squadron | High Seas Fleet | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None |

|

||||||

The scuttling of the German fleet was a dramatic event that happened right after World War I. It took place at Scapa Flow, a naval base in the Orkney Islands of Scotland. The German High Seas Fleet was kept there after the war ended, while leaders decided what would happen to the ships.

Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, who was in charge of the German fleet, made a big decision. He worried that the British might take the ships, or that Germany might restart the war and use the ships against them. So, he decided to sink his own fleet. This happened on June 21, 1919. British ships tried to stop them, but 52 out of 74 German ships sank. Many of these sunken ships were later pulled up and taken apart for scrap metal. The ships that are still underwater are now popular places for divers to explore. They are also a special source of low-background steel, which is used in sensitive scientific equipment.

Contents

Why Did the Ships Sink Themselves?

World War I ended on November 11, 1918, when Germany signed an agreement to stop fighting. The winning countries, called the Allied powers, decided that Germany's U-boats (submarines) had to be given up. But they couldn't agree on what to do with Germany's large surface ships.

The Americans suggested keeping the ships in a neutral country until a final decision was made. But Norway and Spain, the countries asked, said no. A British admiral, Rosslyn Wemyss, suggested that the German fleet be kept at Scapa Flow. Only a small crew of German sailors would stay on board, and the British Grand Fleet would guard them.

Germany was told these terms on November 12, 1918. They had to get their High Seas Fleet ready to sail by November 18. If not, the Allies would take over Heligoland, a German island.

On November 15, a German admiral named Hugo Meurer met with British Admiral David Beatty on Beatty's ship, HMS Queen Elizabeth. Admiral Beatty explained the terms. German U-boats would surrender at Harwich. The main fleet would sail to the Firth of Forth in Scotland and surrender to Beatty. From there, they would be taken to Scapa Flow and kept there until a peace treaty was signed.

Admiral Meurer asked for more time. He knew that many German sailors were unhappy and might not follow orders. He eventually signed the agreement after midnight.

The German Fleet Surrenders

The first German ships to surrender were the U-boats, starting on November 20, 1918. In total, 176 U-boats were handed over. Admiral Franz von Hipper, the German fleet commander, refused to lead his fleet to surrender. Instead, he sent Admiral Ludwig von Reuter.

On November 21, the German fleet met the British light cruiser Cardiff. The British ship led them to meet over 370 ships from the Grand Fleet and other Allied navies. There were 70 German ships in total. Two ships, the battleship König and the light cruiser Dresden, had engine problems and couldn't make it. One destroyer, V30, hit a mine and sank.

The German ships were escorted into the Firth of Forth and anchored. Admiral Beatty sent them a message:

The German flag will be taken down at sunset today and will not be put up again without permission.

Between November 25 and 27, the fleet moved to Scapa Flow. The destroyers went to Gutter Sound, and the larger battleships and cruisers went to the north and west of Cava Island. In the end, 74 ships were kept there. The last ship to arrive was the battleship Baden on January 9, 1919. British ships guarded the interned German fleet.

Life in Captivity

Life for the German sailors on the interned ships was very difficult. A historian named Arthur Marder said it was "complete demoralization." This was because of several problems:

- Lack of discipline: Sailors often didn't follow orders.

- Poor food: Food sent from Germany was not good and boring.

- No fun activities: Sailors were not allowed to go ashore or visit other German ships.

- Slow mail: Letters to and from Germany took a long time.

These problems made some ships very dirty. British officers who visited were shocked by the conditions. Sailors tried to catch fish and seagulls to add to their food. They also received a lot of brandy. British officers were only allowed to visit for official reasons. All mail was checked by the British. German sailors received cigarettes or cigars, but they had no dentists, and the British wouldn't provide dental care.

Admiral Reuter was in charge of the interned ships. He used a small British boat to visit ships and send orders. His staff could sometimes visit other ships to arrange for sailors to go home. Reuter's health was not good. He moved his flag to the light cruiser Emden because a group of revolutionary sailors called the "Red Guard" kept him from sleeping.

Over seven months, the number of German sailors was greatly reduced. Many were sent back to Germany, leaving only about 4,815 men. About 100 men were sent home each month.

Meanwhile, leaders were discussing the fate of the ships at the Paris Peace Conference. France and Italy wanted some of the ships. Britain wanted them all destroyed. They knew that if the ships were divided among the Allies, it would reduce Britain's naval advantage.

Under the Armistice rules, Germany was not allowed to destroy their ships. British admirals had plans to take over the German ships if they tried to sink them. They even suggested taking the ships anyway and holding the crews on land. But these ideas were not acted upon.

Admiral Reuter had thought about sinking the fleet as early as January 1919. When he learned about the possible terms of the Treaty of Versailles in May 1919, he started making detailed plans to scuttle his ships. He was told that the fleet should be sunk at all costs. More sailors were sent home on June 18, 1919. This left Reuter with only loyal men to carry out his plan.

On June 18, he sent out orders. Paragraph 11 said: "It is my intention to sink the ships only if the enemy should attempt to obtain possession of them without the assent of our government." He meant that if the British tried to take the ships without Germany's permission, he would sink them. If Germany agreed to hand over the ships in the peace treaty, they would be given up.

The signing of the Treaty of Versailles was planned for noon on June 21, 1919. The British First Battle Squadron was ready to board the German ships to see if they were preparing to sink them. On June 13, Admiral Madden asked for daily updates on Germany's attitude towards the peace terms. But he was told there was "no reliable indication."

Admiral Fremantle, who was guarding the German ships, planned to seize them at midnight on June 21/22. He thought the treaty would be signed by then. Admiral Madden approved the plan on June 19. But Madden was told the deadline for signing the treaty was moved to 7:00 PM on June 23, and he forgot to tell Fremantle. Fremantle saw the news in a newspaper and thought it was true.

Fremantle had orders to practice his battleships against torpedo attacks. This needed good weather. The weather on the night of June 20 was good, so Fremantle ordered his squadron to sea at 9:00 AM on June 21. The plan to seize the German ships was put off until his squadron returned on June 23, after the treaty deadline. Fremantle later said he unofficially told Reuter that the armistice was still in effect before he left.

The Fleet Sinks

Around 10:00 AM on June 21, 1919, Admiral Reuter sent a signal telling the fleet to get ready to sink. At about 11:20 AM, the final signal was sent: "To all Commanding Officers and the Leader of the Torpedo Boats. Paragraph Eleven of to-day's date. Acknowledge. Chief of the Interned Squadron."

The scuttling began right away. Sailors opened valves to let water in, smashed internal pipes, and opened drain valves. Portholes were already loose, and watertight doors were left open to help the water spread. One German commander wrote that before June 21, the valves were prepared to be opened easily, and large hammers were placed next to them.

Nothing seemed to happen until noon. Then, the Friedrich der Grosse began to lean heavily to the right, and all the ships raised the Imperial German flag. The crews then started to leave their ships.

The British naval forces left at Scapa Flow were small: three destroyers (one was being repaired), seven fishing boats, and some smaller boats. Fremantle started getting news of the scuttling at 12:20 PM. He canceled his squadron's exercise at 12:35 PM and rushed back to Scapa Flow. He and some ships arrived at 2:30 PM, but only the largest ships were still floating. He had radioed ahead, ordering all available boats to try and stop the German ships from sinking or to push them onto the shore.

The last German ship to sink was the battlecruiser Hindenburg at 5:00 PM. By then, 15 large ships had sunk, and only the Baden survived. Four light cruisers and 32 destroyers also sank. Sadly, nine German sailors were killed and about 16 were injured while trying to get to land in their lifeboats.

In the afternoon, 1,774 German sailors were picked up and taken to Invergordon. Admiral Fremantle declared that the Germans would be treated as prisoners of war because they had broken the armistice. They were sent to prisoner-of-war camps. Reuter and some of his officers were brought onto the deck of HMS Revenge. Fremantle, through an interpreter, said their actions were dishonorable. Reuter and his men listened without showing any emotion. Admiral Fremantle later said he felt some sympathy for Reuter, who had kept his dignity in a very difficult situation.

What Happened Next?

France was upset that the German fleet was gone, as they had hoped to get some of the ships. But a British admiral, Wemyss, privately said:

I look upon the sinking of the German fleet as a real blessing. It solves, once and for all, the difficult question of how to divide these ships.

German Admiral Reinhard Scheer was proud of the scuttling:

I am happy. The shame of surrender has been wiped from the German Fleet's honor. The sinking of these ships has shown that the fleet's spirit is not dead. This last act follows the best traditions of the German Navy.

Out of the 74 German ships at Scapa Flow, 15 of the 16 large battleships and battlecruisers, 5 of the 8 cruisers, and 32 of the 50 destroyers sank. The rest either stayed afloat or were moved to shallower water and pushed onto the shore. These ships were later given to the Allied navies.

Most of the sunken ships were left at the bottom of Scapa Flow at first. It was too expensive to pull them up, and there was already a lot of scrap metal after the war. But locals complained that the wrecks were dangerous for boats. So, in 1923, a company was formed to raise them. They pulled up four sunken destroyers.

Around this time, a businessman named Ernest Cox got involved. He bought 26 destroyers from the British for £250. He also bought the large battlecruisers Seydlitz and Hindenburg. He started pulling up the destroyers using an old German dry dock that he changed. He managed to lift 24 of his 26 destroyers in about a year and a half. Then he started working on the bigger ships.

Cox developed a new way to salvage ships. Divers would patch holes in the sunken ships. Then, air was pumped into the hulls to push the water out, making the ships float to the surface. Once floating, they could be towed away to be broken up. Using this method, he refloated several ships. His methods were expensive. For example, raising Hindenburg cost about £30,000.

A coal strike in 1926 almost stopped his work. But Cox found coal in the sunken Seydlitz and used it to power his machines until the strike ended. Raising Seydlitz was also very hard. The ship sank again during the first attempt, damaging most of his equipment. But Cox didn't give up. He tried again. He even told workers to sink Seydlitz again when it accidentally refloated while he was on vacation! He wanted to be there with news cameras when it was raised a third time.

Cox's company eventually raised 26 destroyers, two battlecruisers, and five battleships. He sold his remaining interests and retired, known as the "man who bought a navy." Another company continued the work, raising five more cruisers, battlecruisers, and battleships before World War II began.

The remaining wrecks are in deeper water, up to 47 meters (154 feet) deep. It's not worth the cost to raise them now. They have been sold several times, and small pieces of steel are still sometimes recovered. This low-background steel is special because it was made before any nuclear contamination from atomic bombs. So, it's used in very sensitive devices like Geiger counters.

In 2001, the seven remaining wrecks were protected under a law for ancient monuments. Divers can visit them, but they need a permit. The story of the Scapa Flow scuttling became a symbol of defiance for new German navy recruits in the 1930s. The last known living person who saw the scuttling was Claude Choules, who passed away in 2011 at 110 years old. In 2019, three of the unsalvaged battleships, Markgraf, König, and Kronprinz Wilhelm, were sold on eBay for £25,500 each to a company in the Middle East. The cruiser Karlsruhe sold for £8,500 to a private buyer in England.

100th Anniversary Event

On Friday, June 21, 2019, two ceremonies were held to mark 100 years since the German High Seas Fleet was scuttled. Admiral von Reuter's grandson and three great-grandsons attended both events. The morning ceremony, called 'Reflection at Sea,' took place in the middle of Scapa Flow at 11:00 AM. Dive boats, a ferry, a lifeboat, and two ships from the Northern Lighthouse Board were there. The second ceremony was held at the Royal Naval Cemetery in Lyness, by the graves of the German sailors who died during the scuttling.

List of Ships Scuttled or Beached

| Name | Type | Sunk/Beached | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baden | Battleship | Beached | Given to the British, sunk as a target in 1921 |

| Bayern | Battleship | Sunk 14:30 | Pulled up in September 1933 |

| Friedrich der Grosse | Battleship | Sunk 12:16 | Pulled up in 1937 |

| Grosser Kurfürst | Battleship | Sunk 13:30 | Pulled up in April 1938 |

| Kaiser | Battleship | Sunk 13:15 | Pulled up in March 1929 |

| Kaiserin | Battleship | Sunk 14:00 | Pulled up in May 1936 |

| König | Battleship | Sunk 14:00 | Still underwater |

| König Albert | Battleship | Sunk 12:54 | Pulled up in July 1935 |

| Kronprinz Wilhelm | Battleship | Sunk 13:15 | Still underwater |

| Markgraf | Battleship | Sunk 16:45 | Still underwater |

| Prinzregent Luitpold | Battleship | Sunk 13:15 | Pulled up in March 1929 |

| Derfflinger | Battlecruiser | Sunk 14:45 | Pulled up in August 1939 |

| Hindenburg | Battlecruiser | Sunk 17:00 | Pulled up in July 1930 |

| Moltke | Battlecruiser | Sunk 13:10 | Pulled up in June 1927 |

| Seydlitz | Battlecruiser | Sunk 13:50 | Pulled up in November 1929 |

| Von der Tann | Battlecruiser | Sunk 14:15 | Pulled up in December 1930 |

| Bremse | Cruiser | Sunk 14:30 | Pulled up in November 1929 |

| Brummer | Cruiser | Sunk 13:05 | Still underwater |

| Cöln | Cruiser | Sunk 13:50 | Still underwater |

| Dresden | Cruiser | Sunk 13:50 | Still underwater |

| Emden | Cruiser | Beached | Given to the French, broken up in 1926 |

| Frankfurt | Cruiser | Beached | Given to the Americans, sunk as a target in 1921 |

| Karlsruhe | Cruiser | Sunk 15:50 | Still underwater |

| Nürnberg | Cruiser | Beached | Given to the British, sunk as a target in 1922 |

| S32 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in June 1925 |

| S36 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in April 1925 |

| G38 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in September 1924 |

| G39 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in July 1925 |

| G40 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in July 1925 |

| V43 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the Americans, sunk as a target in 1921 |

| V44 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the British, broken up in 1922 |

| V45 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in 1922 |

| V46 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the French, broken up in 1924 |

| S49 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in December 1924 |

| S50 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in October 1924 |

| S51 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the British, broken up in 1922 |

| S52 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in October 1924 |

| S53 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in August 1924 |

| S54 | Destroyer | Sunk | Partially pulled up |

| S55 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in August 1924 |

| S56 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in June 1925 |

| S60 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the Japanese, broken up in 1922 |

| S65 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in May 1922 |

| V70 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in August 1924 |

| V73 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the British, broken up in 1922 |

| V78 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in September 1925 |

| V80 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the Japanese, broken up in 1922 |

| V81 | Destroyer | Beached | Sank on the way to be broken up |

| V82 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the British, broken up in 1922 |

| V83 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in 1923 |

| V86 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in July 1925 |

| V89 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in December 1922 |

| V91 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in September 1924 |

| G92 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the British, broken up in 1922 |

| V100 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the French, broken up in 1921 |

| G101 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in April 1926 |

| G102 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the Americans, sunk as a target in 1921 |

| G103 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in September 1925 |

| G104 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in April 1926 |

| B109 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in March 1926 |

| B110 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in December 1925 |

| B111 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in March 1926 |

| B112 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in February 1926 |

| V125 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the British, broken up in 1922 |

| V126 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the French, broken up in 1925 |

| V127 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the Japanese, broken up in 1922 |

| V128 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the British, broken up in 1922 |

| V129 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in August 1925 |

| S131 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in August 1924 |

| S132 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the Americans, sunk in 1921 |

| S136 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in April 1925 |

| S137 | Destroyer | Beached | Given to the British, broken up in 1922 |

| S138 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in May 1925 |

| H145 | Destroyer | Sunk | Pulled up in March 1925 |

See also

In Spanish: Hundimiento de la flota alemana en Scapa Flow para niños

In Spanish: Hundimiento de la flota alemana en Scapa Flow para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |