Recruitment to the British Army during World War I facts for kids

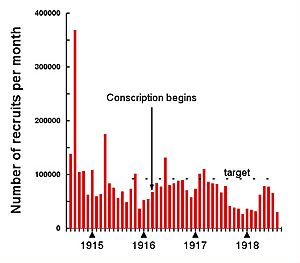

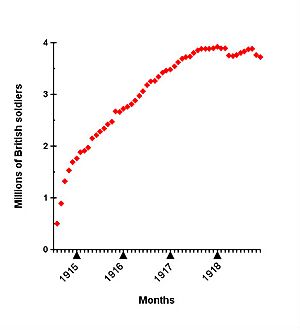

In early 1914, the British Army had about 710,000 men, including those in reserve. Only around 80,000 were professional soldiers ready for battle. By the end of the First World War, over five million men from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland had joined up. This was almost a quarter of all the men in the country. About 2.67 million joined willingly, while 2.77 million were made to join through conscription (a forced enlistment). The number of new recruits joining the army each month changed a lot.

Contents

Joining the Army in August 1914

When the war started on August 4, 1914, the regular British Army had 247,432 serving soldiers. This number did not include reservists who could be called back, or the part-time volunteers of the Territorial Army. About one-third of the regular soldiers were in India and could not join the fight in Europe right away.

For 100 years, the British government and public did not like the idea of conscription for wars in other countries. At the start of World War I, the British Army had six infantry divisions and one cavalry division in the UK. Four other divisions were stationed overseas. There were also fourteen Territorial Force divisions and 300,000 soldiers in the Reserve Army.

Lord Kitchener, who was the Secretary of State for War, thought the Territorial Force was not well trained. He believed the regular army should not be used in early battles. Instead, he wanted them to help train a new army of 70 divisions. This new army would be as big as the French and German armies. Kitchener believed the war would last many years and this large army would be needed.

British Army Medical Checks

All new recruits had to have a physical exam by Army doctors. This was to see if they were healthy enough for military service. Doctors used a system of numbers and letters to describe each recruit's health. Here are the categories the British Army used in 1914:

- A Able to march, see well enough to shoot, hear well, and handle active service.

-

- A1 Fit to be sent overseas, both physically and mentally, and trained.

- A2 Like A1, but without the training part.

- A3 Men who had returned from the Expeditionary Force, ready except for their physical condition.

- A4 Men under 19 who would be A1 or A2 when they turned 19.

- B No serious diseases. Able to serve on supply lines in France or in army bases in hot countries.

-

- B1 Able to march 5 miles, see well enough to shoot with glasses, and hear well.

- B2 Able to walk 5 miles, see and hear well enough for everyday tasks.

- B3 Only good for desk work.

- C No serious diseases. Able to serve in army bases at home.

-

- C1 Able to march 5 miles, see well enough to shoot with glasses, and hear well.

- C2 Able to walk 5 miles, see and hear well enough for everyday tasks.

- C3 Only good for desk work.

- D Unfit now, but could be fit within 6 months.

-

- D1 Regular soldiers from Royal Artillery (RA), Royal Engineers (RE), or infantry in special training camps.

- D2 Regular soldiers from RA, RE, or infantry in their home bases.

- D3 Men in any base or unit waiting for medical treatment.

How Exams Were Done

Medical exams followed strict rules from the War Office, set on August 1, 1914. Recruits needed to meet basic requirements for height, weight, chest size, and age, based on a standard chart. Doctors could guess a recruit's "apparent age" if they did not have proof of age. They would look at how the person appeared and their body size.

Doctors also noted a recruit's intelligence, voice, and character. They would ask questions to create a psychological profile. This helped decide if the person was fit for military service.

Why Some Were Rejected

Many medical reasons could make recruits unfit for service.

- Any signs of tuberculosis (a lung disease).

- Any respiratory tract infections (breathing problems).

- Palpitations (fast heartbeats) or heart disease.

- Generally poor health.

- Poor eyesight.

- Hearing loss.

- Stammering (speech difficulty).

- Tooth decay that made eating hard.

- Deformed chest or joints.

- Abnormal curve of the spine.

- Low intelligence.

- Hernia (a bulge in the body).

- Haemorrhoids (swollen veins).

- Varicose veins or varicocele (swollen veins).

- Long-lasting skin problems.

- Long-lasting sores.

- Fistula (an abnormal connection between body parts).

- Any other disease or physical problem preventing military service.

Volunteers, 1914–1915

In 1914, Britain had about 5.5 million men old enough for the military. Another 500,000 turned 18 each year. The first call for 100,000 volunteers came on August 11. Another 100,000 were asked for on August 28. By September 12, almost half a million men had joined. About 250,000 underage boys also volunteered. They often lied about their age or used false names. If their lie was found out, they were always rejected.

A unique idea was the creation of 'pals battalions'. These were groups of men from the same factory, football team, or bank who joined and fought together. Lord Derby first suggested this idea. In just three days, he had enough volunteers for three battalions. Lord Kitchener quickly approved the idea, and many groups joined. For example, Manchester formed nine specific pals battalions. Accrington, a smaller town, formed one. A sad result of pals battalions was that a whole town could lose many of its young men in a single fierce battle.

The women's suffrage movement was divided. Most members became very patriotic. They asked their members to give white feathers (a sign of being a coward) to men of military age in the streets. This was meant to shame them into joining the army. After some men were attacked, the Silver War Badge was given to those who were not eligible or had been medically discharged.

Popular music hall performers also helped with recruitment. Harry Lauder toured, asking young men to join the army on stage. He often offered "ten pounds for the first recruit tonight." Marie Lloyd sang a recruiting song called "I didn't like you much before you joined the army, John, but I do like you, cockie, now you've got yer khaki on." Vesta Tilley sang "The Army of Today's alright."

About 1.5 million men were "starred," meaning they were kept in important jobs. This reduced the number of available recruits. Also, almost 40 percent of volunteers were rejected for health reasons. Many people in the UK were not well-fed. For example, working-class 15-year-olds were, on average, only 157 cm (5 ft 2 in) tall. Upper-class 15-year-olds were 168 cm (5 ft 6 in) tall.

Lord Kitchener believed Britain needed a huge army for a long war. He argued that Britain had to raise as many soldiers as France and Germany. His goal was 70 divisions. The army asked for 92,000 recruits each month, but fewer men were volunteering. The clear solution was conscription, but this was a big political debate. Many politicians, including Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, were against forcing people to join. However, by 1915, they started to change their minds.

On July 15, 1915, the National Registration Act was passed. One month later, a census was taken of every citizen aged 15 to 65. About 29 million forms were filled out. Each person received a pink registration card with their information. These records were supposed to be destroyed in 1921. However, some survived, including forms for 2,409 women in Cirencester, which are now public.

In September 1915, Arthur Henderson, the Minister of Education and the only Labour member in the Cabinet, gave a strong warning. He said many working men would resist serving a country where they had no real say in the government. They did not like the idea of being forced to fight and possibly die by a Parliament they could not vote for. Forty percent of men over 21 could not vote at that time. To them, conscription felt like another way rich people were taking away workers' rights. The government's only argument was that it was absolutely necessary to win the war. Henderson's own son was killed in the war a year later.

The Derby Scheme

The Derby Scheme was started in late 1915 by the Earl of Derby. He was Kitchener's new Director General of Recruiting. The scheme aimed to find out how many new recruits could be signed up. Canvassers (people who went door-to-door) visited eligible men at home. They tried to persuade them to "volunteer" for war service.

When the scheme was announced, more people joined at first. Some preferred to go to the recruiting office rather than wait for a canvasser. The process began with each eligible man's registration card from the August 1915 National Registry. This information was sent to his local recruiting committee. This committee chose "tactful and influential men" as canvassers. These canvassers were not eligible for service themselves. They visited men in their homes. Many canvassers had political experience. Veterans and fathers of serving soldiers were the most effective. Some canvassers even used threats to persuade men. Women were not allowed to canvas, but they helped by tracking men who had moved.

Every man received a letter from the Earl of Derby. It explained the program and said that Britain was "fighting... for its very existence." Men had to say if they were willing to sign up.

Those who agreed had to go to their recruiting office within 48 hours. Some went right away with the canvasser. If they passed a medical exam, they were sworn in and paid a small "signing bonus." The next day, they were moved to Army Reserve B. All who enlisted, or were officially rejected, received a khaki armband with the Royal Crown. This also applied to men in essential jobs or those already discharged. This practice stopped when conscription began in January 1916.

The enlistee's information was copied onto another card. This was used to put him into one of 46 age groups for married or unmarried men. The scheme promised that only entire groups would be called for active service, with 14 days' notice. Single men's groups would be called before married men's groups. Men who married after the scheme started were still counted as single. Married men were told their group would not be called if too few single men signed up, unless conscription was introduced.

The Derby Scheme took place in November and December 1915. It got 318,553 healthy single men to sign up. However, 38% of single men and 54% of married men resisted the pressure to enlist. So, the British Government decided to force people to join. They passed The Military Service Act for compulsory conscription on January 27, 1916. This was to ensure enough soldiers for the growing number of casualties overseas.

Conscription 1916–1918

Since not enough men volunteered, the Military Service Bill was introduced in January 1916. This was the first time Britain had compulsory conscription. Every unmarried man and widower without children, aged 18 to 41, had three choices:

- Join the army right away.

- Sign up right away under the Derby Scheme.

- Or, on March 2, 1916, be automatically considered to have joined.

In May 1916, the law was extended to married men. In April 1918, the upper age limit was raised to 50 (or 56 if needed). Ireland was not included because of the 1916 Easter Uprising. However, many Irish men still volunteered.

One immediate effect of conscription was the largest protest Britain had seen since 1914. Thousands marched from London's East End to Trafalgar Square. They listened to speeches from Sylvia Pankhurst and a Glasgow politician. The event ended violently when soldiers and sailors attacked the crowd, tearing banners and throwing dye in their faces.

As Arthur Henderson had warned, forced enlistment was not popular. By July 1916, 93,000 men (30%) called for service did not show up. (They had little chance of escaping, though a few lucky ones were hidden by supporters.) Also, 748,587 men claimed an exemption. Men, or their employers, could appeal to a civilian Military Service Tribunal in their area. They could claim they were doing important national work, faced business or family hardship, were medically unfit, or were conscientious objectors (meaning they refused to fight for moral or religious reasons).

Dealing with these cases filled the courts. However, the appeal tribunals often had low standards. In York, a case was decided in about eleven minutes. In Paddington, London, two minutes was typical. Besides those who objected to joining, 1,433,827 men were already "starred" for being in war-related jobs, being sick, or already discharged due to illness. The forced conscription act ultimately did not fully meet the government's need for soldiers.

Only two percent of those appealing were conscientious objectors. About 7,000 of them were given non-fighting duties. Another 3,000 ended up in special work camps. 6,000 were sent to prison. Forty-two were sent to France, where they could have faced a firing squad. Thirty-five were sentenced to death but immediately pardoned, receiving ten years of hard labor instead.

Many who appealed were given some kind of exemption. This was usually temporary (a few weeks to six months) or depended on their work or home situation remaining serious enough. In October 1916, 1.12 million men had tribunal exemptions or pending cases. By May 1917, this number fell to 780,000 exempt and 110,000 pending. At this point, 1.8 million men were exempt. This was more men than were serving overseas with the British Army. Some men were exempted if they joined the Volunteer Training Corps for part-time training and home defense duties. By February 1918, 101,000 men had been sent to this Corps by the tribunals.

A newspaper report on February 17, 1916, listed five examples of appeals for exemption from conscription and their results.

| Appealer(s) | On behalf of | Plea | Result of plea |

|---|---|---|---|

| a firm of art dealers | their clerk | busy with a big export trade | appeal rejected |

| Royal Academy | W. R. H. Lamb (its secretary) | busy with 12,000 incoming works; no available replacement | his conscription was delayed 3 months |

| a tobacco and cigarette manufacturers | their blender | "we supply army officers" | appeal rejected |

| Oswald Stoll | J. P. Seaborn (artist and photographer) | busy making images, etc. for Mr. Stoll's theatres | wait while accumulating a list of about 40 appealed employees |

| Mr. Brenman (clog dancer, member of the music hall act Five Dorinos) | needed to hold group together | his conscription was delayed 1 month | |

In 1917, the House of Commons passed a bill to give all males over 21 the right to vote (and many women too). But it did not become law until February 6, 1918. In the same month, job exemptions were removed for men aged 18 to 23. By October 1918, 2,574,860 men were in reserved jobs. Men aged 18 and a half were sent to the front lines starting in March 1918. This broke a promise to keep them safe until they were 19. There were also problems with men being fit for active service. There simply were not enough healthy men. Recruits were put into three classes: A, B, and C, based on their fitness for front-line service. In 1918, 75 percent were Class A. Some Class B men also had to be sent to the trenches.

The number of men forced to join is usually calculated by assuming all recruits after March 1, 1916, were conscripts. This would be 1,542,807 men, or 43.7% of all who served in the Army during the war. However, the Derby Scheme had already enlisted 318,553 single men in Special Reserve B. These men were called up in spring 1916. This means the number of truly conscripted men is closer to 37%. It is harder to categorize married men who signed up under the Derby plan because they were not called from the Reserve but swept up with everyone else. It seems that slightly less than 35% of the men in the army were forced to serve.

Ireland

In 1918, a law was planned to extend conscription to Ireland. This was strongly opposed by many Irish nationalists and the Catholic Church in Ireland. The main role of Sinn Féin in this movement made them very popular before the November general election.

Advertising for Recruits

Official advertising for recruits was managed by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee (PRC). However, private efforts, like the one by the London Opinion magazine with the famous image of Kitchener, were also made. Posters were printed in different sizes for different places. Common sizes were 102 cm by 76 cm (40 by 30 in) and 51 cm by 38 cm (20 by 15 in). The PRC included the Prime Minister and leaders of political parties. Other representatives, like those from the Trades Union Congress, later joined. Its sub-committees handled creating and printing recruiting materials.

During the war, the PRC created 164 poster designs and 65 pamphlets. In total, over 54 million pieces of advertising were produced. This cost £40,000. Based on the number of posters produced, the most popular official PRC posters were:

- "Lord Kitchener", 1915. Posters No. 113 and 117, 145,000 copies.

- "Remember Belgium", 1914–1915. PRC16 and PRC 19. It showed a British soldier guarding while a woman fled her burning home. 140,000 copies.

- "Take Up The Sword of Justice", September 1915. PRC 105, 106, 11. By Bernard Partridge. It showed the sinking of the Lusitania in the background with a figure offering a sword. 105,000 copies.

- "Serve The Guns" May 1915. PRC 85a, 85b, 85c. It showed a soldier and a munitions worker shaking hands. 101,000 copies.

- "He did his duty. Will You do Yours". December 1914. PRC 20. A portrait of Frederick Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts (who had recently died after visiting Indian troops) with his Victoria Cross. 95,000 copies.

The "King's Message" was reprinted as a poster and ran to 290,000 copies.

Recruiting Staff

Some notable men who worked as army recruiters during the war included:

- Sergeant John Doogan, who received the Victoria Cross for bravery.

- Captain Samuel Hoare, who later became an intelligence officer and a Conservative politician.

- Major Lionel Nathan de Rothschild, a banker and Conservative Member of Parliament (he received an OBE for his services).

See also

- British Army First World War reserve brigades

- Conscription in Australia

- Conscription Crisis of 1917 in Canada

- Compulsory military training in New Zealand

- No-Conscription Fellowship

- Opposition to World War I

- Temporary gentlemen

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |