Temporary gentlemen facts for kids

Temporary gentlemen was a special name for officers in the British Army who had temporary jobs as officers, especially during big wars. These officers often came from regular families, not the rich, traditional "officer class." The name suggested they would go back to their old lives after the war.

Historically, most British Army officers were from wealthy families. It cost a lot of money to join and be an officer, so only the rich could afford it. But when World War I started, the army needed many more officers quickly. Over 200,000 new officers joined, many with temporary roles. A lot of these new officers came from middle-class or working-class backgrounds.

After the war, many of these "temporary gentlemen" found it hard to go back to their old jobs, which often paid less. Some even faced tough times. However, some became famous writers, and their stories appeared in books, plays, and movies.

The term "temporary gentlemen" was used again during World War II for similar reasons. After this war, the army tried to help officers return to civilian life more smoothly. The name was even used for officers who joined through National Service until 1963. It was also used to describe conscript officers in the Portuguese Army in the 1960s and 70s.

Contents

Becoming an Officer: A Look Back

For a long time, becoming an officer in the British Army meant you had to buy your position! This was called the "purchase system." It was very expensive, so only rich families could afford it. For example, a high-ranking officer job could cost as much as a large house today. This system meant that only the wealthy, often younger sons of noble families, could become officers. They could even sell their officer jobs when they retired. This system also saved the government money because they didn't have to pay officers a high salary or pension.

Because of this, officers were usually seen as "gentlemen," a term for people from the upper classes. Many went to special private schools where they started training to be officers from a young age.

Even after the purchase system ended in 1871, it was still mostly rich people who became officers. Officers were expected to play expensive sports like polo and pay high bills at their army clubs (called "mess"). They also had to buy their own uniforms and equipment, which cost a lot. In 1900, a young officer in a fancy cavalry regiment needed a private income of about £500 a year, which was a huge amount of money back then. This meant that most people from working-class families couldn't afford to be officers.

Before World War I, only a very small number of soldiers from the regular ranks became officers, usually for special jobs like veterinarians.

World War I: A New Kind of Officer

The term "temporary gentlemen" became well-known during World War I. It described officers who were given temporary roles just for the war. Many of these men were not from the traditional wealthy families. Older, traditional officers sometimes used the term to remind the new officers that they were expected to go back to their old lives after the war. This often felt insulting to the new officers. However, as the new officers proved themselves brave and capable in battle, the term was used less often. Some even started using it themselves in a joking way.

Sometimes, the opposite happened. Some wealthy men chose to serve as regular soldiers instead of becoming officers. For example, David Lindsay, 27th Earl of Crawford, a nobleman, served as a lance corporal at age 45.

The War Begins: More Officers Needed

When World War I began, the British Army had about 10,800 officers. But over the next four years, more than 200,000 new men became officers, mostly on temporary commissions. This meant they were expected to return to their civilian jobs after the war.

At first, some experienced non-commissioned officers (NCOs) and warrant officers from the regular army were made officers. In October 1914, 187 men were promoted this way, which was a huge number for the army. By the end of 1918, about 10,000 soldiers from the ranks had become officers.

Some NCOs who became temporary officers faced money problems because they lost some of their old pay. This made some men refuse officer roles. Later in the war, the army started giving grants and allowances to officers to help with costs. By 1916, a new officer could earn over £210 a year, plus some civilian employers continued to pay half wages. So, money worries became less of an issue for temporary gentlemen later in the war.

It was sometimes hard for former NCOs to become officers. They were used to being in charge of many men, but as a new officer, they had smaller commands. They were also often moved to new units because the army didn't want officers to be too friendly with their old soldiers. Some regular soldiers didn't like officers who had come from the ranks because they knew too much about army life and were harder to trick.

In the early months of the war, the army grew very quickly. Many new recruits joined Kitchener's Army, a volunteer force. At first, most new officer jobs went to men from the traditional officer class. However, there was a preference for those who had military training from school, which often meant students from well-known private schools.

Future prime minister Harold Macmillan was a temporary officer himself. Even though he came from a good family, he used the term "temporary gentlemen" to describe others, showing how the term was used to highlight social differences.

More Temporary Officers Join

Many of the original officers in the British Expeditionary Force were injured or killed in the first year of the war. The army's traditional training schools couldn't produce enough new officers. So, the army started giving out many more temporary commissions based on skill, not just background. By February 1916, over 80,000 temporary commissions had been given out.

The army also set up officer cadet battalions, where all potential officers had to train. Eventually, 23 of these battalions were created, producing over 107,000 temporary officers by the end of the war.

This big change meant that people who wouldn't have been considered "officer material" before the war could now become officers. This included people from the lower middle class and even some from the working class. Many early temporary officers were former clerks, who often had a good education.

The idea of these new officers being "gentlemen" was a bit tricky. They were considered gentlemen only because of their officer role, which was temporary. The expectation was that they would stop being "gentlemen" when the war ended and they returned to their old lives. Even with all these changes, the British Army still expected all officers to act and look like "gentlemen." Some very traditional regiments still preferred officers from wealthy families.

Serving Before Becoming an Officer

In February 1916, the army decided that temporary commissions would only be given to men who had already served for two years as regular soldiers or in officer training units. This rule led to even more working-class men becoming temporary gentlemen. By 1917, each army division had to provide 50 suitable officer candidates each month.

The idea was that the army wanted experienced men who knew how to lead, not just men with money. Some commanders even saw this as a way to get rid of difficult men from their units. However, many NCOs didn't want to leave their friends to go to officer training. Despite this, by the end of the war, more than half of all British officers had served as regular soldiers before becoming officers.

After World War I: Returning Home

Demobilisation: Back to Civilian Life

After the war, temporary gentlemen were quickly sent home. By the end of 1920, over 200,000 officers had left the army. Very few temporary commissions were made permanent.

It was hard for many temporary gentlemen to go back to civilian life, especially those who weren't from wealthy backgrounds. Many had gained more responsibility and power as officers than they ever had before. They expected to keep their higher status, even if they didn't have a good education. They often looked for jobs where they could supervise or control other people.

The government tried to help by setting up a department to find jobs for former officers. At first, they tried to find jobs that matched the officers' wartime rank, but this was later changed back to matching their pre-war social standing and education. This meant that many former officers, even those who saw themselves as "gentlemen," struggled to keep that status after the war.

The government offered training in farming and business, along with grants. But many former officers were unhappy. Some high-ranking officers ended up in much lower jobs, like former colonels working as grocers or majors as salesmen. Some even became railway porters or cab drivers.

Many temporary officers found their financial situation much worse. A junior officer might have earned £300 a year, but many civilian jobs paid less than £150. The government warned them not to expect their army pay to be matched. Thousands of former officers faced hardship, with some even sleeping rough in Hyde Park. Many charities were set up to help them.

The problem got worse in early 1920 as more officers were sent home and there weren't enough jobs. The economy was also slowing down. Unemployment rose sharply. Former officers were not allowed to use job centers or claim unemployment benefits like regular soldiers, which made things even harder. Eventually, most former officers were happy to take almost any job they could find.

Back to Old Ways

After the war, the army quickly went back to its old traditions. The expensive social habits returned, and many temporary gentlemen couldn't afford to stay in the peacetime army. Those who left found they no longer had the same social standing they had enjoyed in the army. Some historians believe the war blurred social lines, making lower-class officers more confident. Others think it just made people more aware of class differences.

Attempts were made to open up the Sandhurst military academy to more people, but with limited success. The high cost of living for officers meant that a private income was still needed. By the mid-1930s, Sandhurst was again mostly filled with students from private schools and sons of officers.

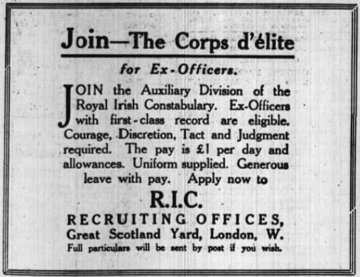

Some former temporary gentlemen found work with the Black and Tans or the Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary. These groups were sometimes made up of men who struggled to adjust to civilian life after the war.

How "Temporary Gentlemen" Appeared in Stories

During the war, newspapers often joked about the social awkwardness of temporary gentlemen. Many wartime books and memoirs, like Robert Graves' Good-Bye to All That, also talked about the tension between regular officers and temporary gentlemen.

Many temporary gentlemen became famous writers, including J. B. Priestley and R. C. Sherriff. Sherriff's famous play Journey's End features a character, Second Lieutenant Trotter, who is a working-class man promoted from the ranks. The "temporary gentleman" became a common character in stories after the war.

The challenges faced by these officers were captured by George Orwell in his novel Coming Up for Air. The main character, a former temporary officer, remembers how they "suddenly changed from gentlemen holding His Majesty's Commission into miserable out-of-works whom nobody wanted."

World War II and Beyond

New Temporary Officers

At the start of World War II, the British Army had only about 14,000 regular officers. With conscription introduced in 1939, the army grew rapidly, and about 250,000 men became officers, many of them "temporary gentlemen."

Before 1939, it was hard for ordinary people to become officers. But the system slowly changed. In 1942, the army introduced the War Office Selection Board (WOSB), where candidates were interviewed by psychologists. This helped improve the quality of officers and also led to more people from different backgrounds becoming officers. Some notable examples included a former blast furnace worker who became a lieutenant and a road sweeper who became a captain. Still, by the end of the war, about 34% of officers still came from private schools.

After World War II

After World War II, the government carefully planned when soldiers and temporary officers would return home. This was done to avoid a sudden rush of people looking for jobs.

A law passed in 1944 required employers to let former employees return to their old jobs. However, many temporary gentlemen chose not to, as they had gained more responsibility and confidence in the army. Some who did return were disappointed, like a Royal Artillery officer who had commanded a gunnery school but ended up making tea in a bank. The government tried to help them find new jobs or training.

Many temporary officers found civilian jobs boring or lower paying than their army roles. Some even became unemployed. They were sometimes criticized for expecting high salaries. It was also hard for some to reconnect with their working-class friends and family.

The term "temporary gentlemen" continued to be used for officers who joined through National Service until 1963, when the British Army became an all-volunteer force. Over the years, the army's officer corps became more diverse. By 1960, fewer officers came from fee-paying schools. In 1972, the term "gentleman" was even removed from a military charge called "conduct unbecoming a gentleman," showing that officers were no longer automatically considered gentlemen just because of their rank.

Other Military Branches

The British Indian Army also had "emergency commissioned officers" during World War II, similar to temporary gentlemen. These officers, both Indian and European, received quick training. There was less tension between these temporary officers and regular officers compared to World War I.

The Royal Navy traditionally recruited officers from wealthy families. While some changes were made during World War I, it was World War II that brought a big shift. Many "temporary gentlemen" from working and middle-class backgrounds joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. This experience led to changes in how the Navy recruited officers after the war. Today, many Navy officers started as regular sailors, and a large percentage identify as coming from working-class backgrounds.

The Royal Air Force (RAF), founded in 1918, also used temporary commissions during World War II. The RAF was seen as more "classless" than the army, and it recruited more temporary gentlemen from lower classes. While Fighter Command was still considered elite, Bomber Command was more focused on skill, as its planes needed technical experts. After the war, the RAF moved towards a more merit-based system for selecting officers.

"Milicianos" in the Portuguese Army

The term milicianos was used for conscript officers in the Portuguese Army in the 1960s and 1970s, and it's been translated as "temporary gentlemen." These officers served in colonial wars. Regular officers sometimes called them "just doctors or lawyers in uniform."

Tensions grew between temporary and regular officers when a rule in 1973 allowed temporary officers to become permanent. This meant some former milicianos could get promoted faster than regular officers. This unhappiness was one of the reasons for the Carnation Revolution in 1974, when the military overthrew the government. Portugal later ended conscription in 2004, moving to an all-professional army.

See also

- Gentleman ranker

- Officer Training Unit, Scheyville

- The Best Years of Our Lives

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |