Siege of Kimberley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Kimberley |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Boer War | |||||||

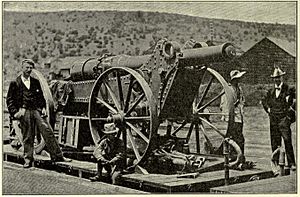

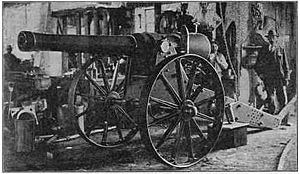

British RML 2.5-inch mountain gun employed in the defence of Kimberley during the Second Boer War |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| >1,600 | 3,000–6,500 Several guns |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 42 killed 135 wounded |

Heavy | ||||||

The Siege of Kimberley was a major event during the Second Boer War. It happened in Kimberley, which is now in South Africa. Forces from the Orange Free State and the Transvaal surrounded this important diamond mining town.

When the war began in October 1899, the Boer forces quickly tried to take Kimberley. The town was not fully ready for a fight. However, the people defending it quickly organized a strong and clever defense. This stopped the Boers from capturing the town.

Outside Kimberley, the Boers treated the land they took as their own. They even changed the name of a nearby town, Barkly West, to Nieu Boshof.

Cecil Rhodes, a very rich man who owned the diamond mines, was in Kimberley during the siege. He helped organize the town's defense. The Boers used powerful cannons to shell the town. They hoped this would make the defenders give up. The engineers from Rhodes's company, De Beers, even built their own huge gun called Long Cecil. But the Boers soon brought an even bigger gun. This new gun scared the people, and many had to hide in the Kimberley Mine.

The British military had to change their war plans. People back home wanted the sieges of Kimberley, Ladysmith, and Mafeking to end first. The first attempt to help Kimberley failed. This was after battles at Modder River and Magersfontein. After 124 days, the siege finally ended on 15 February 1900. A cavalry group led by Lieutenant-General John French broke through. The fight against the Boer general Piet Cronjé continued right after at Paardeberg.

Contents

Why Kimberley Was Important

Before the Second Boer War, Kimberley was the second-largest city in the Cape Colony. It was a busy and rich place. This was because it was the center of diamond mining for the De Beers Mining Company. This company supplied 90% of the world's diamonds.

Kimberley had about 40,000 people, with 25,000 being white. It was one of the few British areas far north in the colony. It was only a few kilometers from the borders of the Boer republics. Cape Town was 1,041 kilometers away by train. Port Elizabeth was 780 kilometers away. The closest Boer towns were Jacobsdal to the south and Boshof to the east.

Getting Ready for the Siege

The De Beers company worried about Kimberley's safety years before the war. They especially worried about attacks from the nearby Orange Free State. In 1896, they created a weapons storage area. They also sent a defense plan to the government and set up a local defense group.

As war seemed more likely, the people of Kimberley asked the leader of the Cape Colony, William Philip Schreiner, for more protection. But he did not think the town was in danger. He refused to send more weapons. In September 1899, he said: "There is no reason whatever for apprehending that Kimberley is or will be in any danger of attack and your fears are therefore groundless."

The town then asked the high commissioner, and this time they had more luck. On 4 October 1899, Major Scott-Turner was allowed to ask volunteers to join the town guard. He also formed the Diamond Fields Artillery. Three days later, Colonel Robert Kekewich took command of the town. He was from the 1st Battalion, Loyal Regiment (North Lancashire). The town was now safe from a quick attack, but not from a long siege.

Colonel Kekewich's troops included four companies of the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment. He also had some Royal Engineers, six small RML 2.5-inch mountain guns, and two machine guns. He also had 120 men from the Cape Police. There were 2,000 volunteer troops, the Kimberley Light Horse, and some older seven-pounder guns. Eight Maxim machine guns were placed on small forts built on top of mining waste piles around the town.

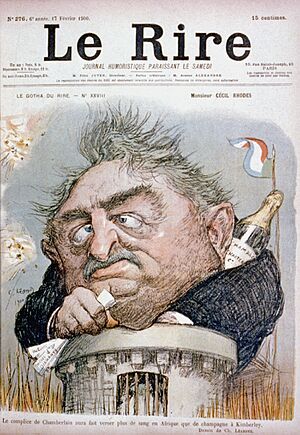

Cecil John Rhodes, who started De Beers, decided to move into the town. People worried that his presence would make the Boers angry. This was because he played a big part in the events that led to the war. So, the mayor of Kimberley and Rhodes's friends tried to stop him. But Rhodes did not listen. He moved into the town just before the siege began. He barely escaped capture on 11 October.

Rhodes's presence was a calculated move. He wanted to force the British government to send help to his mining operations. Since De Beers owned most of the resources in the town, Rhodes became very important in the defense. However, the military felt Rhodes was sometimes a problem. He did not always work well with them. The military and town leaders often disagreed.

Life During the Siege

The conflict at Kimberley began on 14 October 1899. Colonel Baden-Powell told all women and children to leave the town. Some left on a special train. On its way back, this train was captured by Boers. This was the first action of the war near Kimberley.

On 12 October, the Jacobsdal Commando cut the railway line south of Kimberley. The Boers then dug in at Spytfontein. The Boshof Commando cut the railway line north of town. They also shut off the main water supply. Water in the mines became more valuable than diamonds. On 14 October, the Boers cut the telephone line to the Cape. Messages then had to be sent by heliograph (using mirrors) or by dispatch riders. These riders had to travel through dangerous Boer lines. On 15 October, martial law was declared. This meant the military took control.

The cattle outside town were a problem. If left, the Boers would take them. If killed, the meat would spoil in the summer heat. The De Beers chief engineer, George Labram, found a solution. He built an underground refrigeration plant in the Kimberley mine to keep the meat fresh.

The Boer commander, Cornelius Wessels, demanded the town surrender on 4 November. Kekewich refused. When the siege truly began on 6 November, the Boers controlled the railway. Kimberley had limited weapons and ammunition. On 7 November, the Boers started shelling the town. The Boer plan was not to attack directly. Instead, they wanted to wear down the defenders with constant shelling until they gave up. The defenders tried to send away the many mine workers. But the Boers twice forced them back into town. This was likely to put pressure on Kimberley's limited food and water.

Rhodes had his own goals. He loudly demanded that the siege be lifted. He used newspapers and spoke directly to the government. But Kekewich was calmer. He told authorities in Cape Town that the situation was not desperate. He believed he could hold out for weeks. The conflict between the two men grew. The local newspaper, controlled by Rhodes, printed military information without permission. Kekewich got permission to arrest Rhodes if needed.

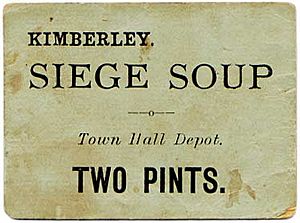

Food and water were carefully managed. Rationing was put in place as supplies ran low. Towards the end of the siege, people had to eat horse meat. Vegetables were hard to grow due to water shortages. The lack of vegetables hurt the poorest people most, especially the 15,000 local workers. A doctor suggested they eat aloe leaves to avoid scurvy. Rhodes organized a soup kitchen.

On 25 November, the British attacked a Boer redoubt (small fort) at Carter's Ridge. They hoped this would help the relief column at Magersfontein. A group of 40 men surprised the Boers. They captured 33 Boers and killed four. Three days later, a second raid failed badly. Major Scott-Turner was among those killed.

The engineers from Rhodes's company, led by George Labram, were key to the town's defense. They built forts, an armored train, a watch tower, shells, and a gun. This gun was called Long Cecil. It was made to help the defenders' weak weapons. Long Cecil could fire a 13 kg shell 6,000 meters. It was finished on 21 January 1900. It worked well against a Boer position that was previously out of reach.

The Big Guns

The Boers responded on 7 February with a much heavier gun. It was a 100-pounder called "Long Tom". This gun had been damaged by British spies at Ladysmith. It was then repaired in Pretoria and brought to Kimberley. Its shells were much bigger than any other siege guns used so far. Its longer range meant it could hit any part of Kimberley.

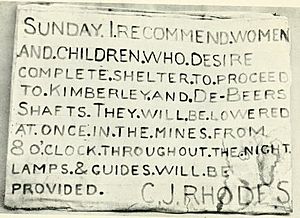

People in town had gotten used to shelling from smaller guns. They could find shelter and continue their lives. But the new gun changed everything. Terrified residents could no longer find safety anywhere above ground. Rhodes put out a notice inviting people to hide in the Kimberley Mine. This was to avoid the deadly shelling.

Luckily for the defenders, the gun did not use smokeless powder. This meant observers could see the smoke. They could give residents up to 17 seconds warning to take cover. Sadly, George Labram, the engineer who built Long Cecil, was killed. He died within a week of the siege's end. He was hit by a shell from the Boer Long Tom gun. Kekewich arranged a full military funeral for him. It was held after dark for safety. The procession was targeted by Boer shelling. A traitor in town lit a flare to guide the enemy.

The Boers surrounded the town for 124 days. They shelled it almost every day, except Sundays. Shelling eased during the Battle of Magersfontein. This was when the Boer guns were moved there temporarily. Kekewich often sent armed reconnaissance missions outside the town's defenses. Sometimes he used the armored train. Some of these fights were fierce, with losses on both sides. But they did not change the situation. In January 1900, General Ignatius Stephanus Ferreira took over the Boer command from Cornelius Wessels.

Help Arrives

The British commander in South Africa, General Sir Redvers Buller, first planned to march on the Boer capitals. But public opinion demanded that Kimberley, Ladysmith, and Mafeking be helped first. This was partly because Rhodes was in Kimberley and was asking for help in London. So, Buller had to change his plans. He divided his forces. Lord Methuen was sent north in December 1899 to help Kimberley and Mafeking.

On 1 December 1899, Methuen's relief column made contact with the defenders. However, Methuen's advance stopped. The Boers caused heavy losses at the Battle of Modder River. They also defeated him at the Battle of Magersfontein. These defeats were called "Black Week" by the British. For two of the four months of the siege, 10,000 British troops were only 19 kilometers from Kimberley. But they could not reach it.

Lord Roberts replaced Buller as British Commander-in-Chief in January 1900. Within a month, Roberts gathered a huge force. He had 30,000 foot soldiers, 7,501 cavalry, and 3,600 mounted infantry. He also had 120 guns. The largest British mounted division ever was created. It was led by Major-General John French. News of the Boer Long Tom gun reached Lord Roberts. On 9 February, he told his officers: "You must relieve Kimberley if it costs you half your forces."

Piet Cronjé thought Roberts would attack from the west. But Roberts ordered a clever move. He sent a brigade 32 kilometers west to Koedoesberg. This made Cronjé think the attack would happen there. But most of the force went south, then east into the Orange Free State. French's cavalry protected the British right side. On 13 February, Roberts started the second part of his plan. French's cavalry would move quickly north, east of Jacobsdal. They would cross the Modder River at Klip Drift.

As French's group neared the Modder River on 13 February, about 1,000 Boers attacked their right side. French moved his troops to face them. This allowed the left side to continue towards Klip Drift. The Boers were completely surprised at Klip Drift. They left their camp and supplies behind. French's tired men and horses were happy to take them. The cavalry had to wait for the foot soldiers to catch up. This was to secure their supply lines before moving to Kimberley.

French's quick move was hard on the horses and men. It was very hot. About 500 horses died or were too tired to ride. When Cronjé saw French's cavalry, he thought the British were trying to pull him east. He sent 900 men with guns to stop the British. French's men left Klip Drift at 9:30 am on 15 February. This was the last part of their journey to Kimberley. They were soon fighting the Boer force.

Rifle fire came from the river. Artillery shells rained down from the hills. The way to Kimberley was straight ahead, through the crossfire. So, French ordered a brave cavalry charge right down the middle. Horses galloped forward, hidden by a huge cloud of dust. The Boers fired from both sides. But the speed of the attack worked. The Boer force was defeated. British losses that day were five dead and 10 wounded. About 70 horses were lost from exhaustion.

The way to Kimberley was open. That evening, General French and his men passed through the empty Boer lines. They relieved Kimberley. It was hard at first to convince the defenders by heliograph that they were British, not Boers. The cavalry had traveled 193 kilometers in four days in the summer heat. When French arrived, he went to Rhodes first, not Kekewich.

French's men did not rest much. Their first night, they were called to try and capture the Long Tom gun. Early on 17 February, they were sent to cut off Cronjé's main force. Cronjé had left Magersfontein and was heading east. Kitchener told French to stop the Boers from escaping. Of French's original 5,000 men, only 1,200 cavalrymen were still fit. Their horses were exhausted.

At dawn, the cavalry headed towards the Boer dust clouds. They soon saw a valley full of Boers, with cattle, 400 wagons, and families. The British started shelling the Boer column. This caused great confusion and panic. Cronjé decided to stay put instead of escaping. This gave French time to call for more troops. The Battle of Paardeberg followed for the next week. It ended with Cronjé's defeat, but at a high cost for the British.

After the Siege

On 17 February, Kekewich was promoted to full colonel. French was promoted to major general. Many medals were given to those who fought. The Kimberley Star was created by Mayor H. A. Oliver. It was not an official military medal. The official awards were clasps for the Queen's South Africa Medal. These were called "Defence of Kimberley" and "Relief of Kimberley."

The British set up a concentration camp at Kimberley. It held Boer women and children, and black refugees. A memorial outside the Newton Dutch Reformed Church remembers those who died there.

The Honoured Dead Memorial was built to remember the defenders who died. Cecil Rhodes asked for it to be built. It was designed by Sir Herbert Baker. Twenty-seven soldiers are buried in the memorial. It was made from stone from the Matopo Hills in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). It has words by Rudyard Kipling: "This for a charge to our children in sign of the price we paid, The price that we paid for freedom that comes unsoiled to your hand; Read, revere and uncover, here are the victors laid, They who died for their City, being sons of the land." Long Cecil, the gun made in the De Beers workshops, is at the base. It faces the Free State. It is surrounded by shells from the Boer Long Tom.

The Sanatorium Hotel, where Cecil Rhodes stayed during the siege, is now the McGregor Museum. The stone he used to get on his horse is still in the gardens. The museum has many exhibits about the siege.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |