Edward Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Earl of Halifax

|

|

|---|---|

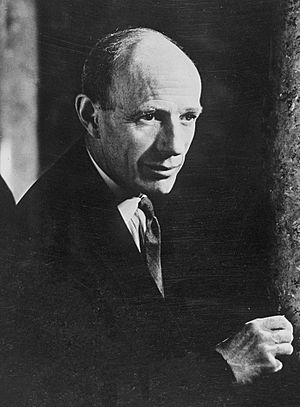

The Earl of Halifax in 1947

|

|

| British Ambassador to the United States | |

| In office 23 December 1940 – 1 May 1946 |

|

| Nominated by | Winston Churchill |

| Appointed by | George VI |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Lothian |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Inverchapel |

| Leader of the House of Lords | |

| In office 3 October 1940 – 22 December 1940 |

|

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Caldecote |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Lloyd |

| In office 22 November 1935 – 21 February 1938 |

|

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Londonderry |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Stanhope |

| Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 21 February 1938 – 22 December 1940 |

|

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | Anthony Eden |

| Succeeded by | Anthony Eden |

| Secretary of State for War | |

| In office 7 June 1935 – 22 November 1935 |

|

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Hailsham |

| Succeeded by | Duff Cooper |

| Lord President of the Council | |

| In office 28 May 1937 – 9 March 1938 |

|

| Prime Minister | Neville Chamberlain |

| Preceded by | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Hailsham |

| Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal | |

| In office 22 November 1935 – 28 May 1937 |

|

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Londonderry |

| Succeeded by | The Earl De La Warr |

| Chancellor of the University of Oxford | |

| In office 1933–1959 |

|

| Preceded by | The Viscount Grey of Fallodon |

| Succeeded by | Harold Macmillan |

| Viceroy and Governor-General of India | |

| In office 3 April 1926 – 18 April 1931 |

|

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | The Earl of Reading |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Goschen (acting) |

| Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries | |

| In office 6 November 1924 – 4 November 1925 |

|

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | Noel Buxton |

| Succeeded by | Walter Guinness |

| President of the Board of Education | |

| In office 24 October 1922 – 22 January 1924 |

|

| Prime Minister | Bonar Law Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | H. A. L. Fisher |

| Succeeded by | Sir Charles Trevelyan |

| Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies | |

| In office 1 April 1921 – 24 October 1922 |

|

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | Leo Amery |

| Succeeded by | Hon. William Ormsby-Gore |

| Member of the House of Lords | |

| Hereditary peerage 5 December 1925 – 23 December 1959 |

|

| Preceded by | Created Baron Irwin in 1925 (inherited his father's titles in 1934) |

| Succeeded by | The 2nd Earl of Halifax |

| Member of Parliament for Ripon |

|

| In office 10 February 1910 – 5 December 1925 |

|

| Preceded by | H. F. B. Lynch |

| Succeeded by | John Hills |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood

16 April 1881 Powderham Castle, Exminster, England |

| Died | 23 December 1959 (aged 78) Garrowby, England |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse |

Lady Dorothy Onslow

(m. 1909) |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, born on April 16, 1881, was a very important British politician in the 1930s. He was known by different titles during his life, including The Lord Irwin and The Viscount Halifax. He held many high-ranking jobs in the government. These included being the Viceroy of India from 1926 to 1931 and the Foreign Secretary from 1938 to 1940.

Halifax was involved in the policy of appeasement towards Adolf Hitler before World War II. This meant trying to give Hitler what he wanted to avoid war. However, after some terrible events, like Kristallnacht (a violent attack against Jewish people in Germany) and Germany taking over Czechoslovakia, Halifax pushed for a stronger approach. He wanted Britain to promise to defend Poland if Germany attacked.

When Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain resigned in May 1940, Halifax was offered the job. But he turned it down, believing that Winston Churchill would be a better leader during the war. A few weeks later, as British forces faced defeat at Dunkirk, Halifax thought about trying to make peace with Italy. But Churchill disagreed strongly. From 1941 to 1946, Halifax served as the British Ambassador to the United States.

Contents

Early Life and School Days

Edward Wood was born on April 16, 1881, at Powderham Castle in England. He came from a well-known family in Yorkshire. His great-grandfather was Earl Grey, famous for Earl Grey tea and for being a Prime Minister who introduced important reforms.

Edward was the sixth child in his family. Sadly, his three older brothers died young. This meant that by age nine, he became the heir to his father's wealth and a future seat in the House of Lords. He grew up in a very religious home and loved hunting. He was a very religious person, which earned him the nickname "Holy Fox."

Edward was born with a left arm that wasn't fully developed and no left hand. But this didn't stop him from enjoying activities like riding, hunting, and shooting. He used a special artificial hand that helped him hold reins or open gates.

He spent his childhood mainly at two family homes in Yorkshire: Hickleton Hall and Garrowby.

Edward went to Eton College and then to Christ Church, Oxford University. He wasn't very interested in student politics but did very well in his studies, earning a top degree in Modern History. He was also part of a private club at Oxford called the Bullingdon Club, known for its wealthy members.

After Oxford, he traveled a lot, visiting places like South Africa, India, Australia, and Canada.

Starting in Politics and War Service

Edward Wood first became a Member of Parliament (MP) for Ripon in Yorkshire in January 1910. He stayed an MP until 1925. Before World War I, he was a captain in a military regiment. When the war started, he pushed for conscription, meaning people would be required to join the army.

He was sent to the front lines in 1916 and rose to the rank of major. After the war, he continued his political career. He was re-elected as an MP several times without anyone running against him.

In 1918, he and another politician, George Lloyd, wrote a paper called "The Great Opportunity." They wanted the Conservative Party to focus on the well-being of everyone in the country, not just individuals.

Early Government Jobs

In April 1921, Edward Wood became the Under-Secretary for the Colonies, working under Winston Churchill. He later became the President of the Board of Education in October 1922. He saw this job as a step towards more important roles.

In November 1924, he was appointed Minister for Agriculture. This was a more demanding job, and he worked on new laws for farming.

Viceroy of India

In October 1925, Edward Wood was offered the very important job of Viceroy of India. This meant he would be the highest British official in India. His grandfather had also worked in India many years before. He accepted the job and was given the title Baron Irwin in December 1925. He arrived in India in April 1926.

Irwin enjoyed the grand ceremonies of being Viceroy. He was a skilled horseman and very tall, standing at 6 feet 5 inches. He was more understanding towards Indian people than previous Viceroys. He wanted Indians to be more united and friendly with Britain. He often spoke about ending violence between Hindus and Muslims.

Simon Commission

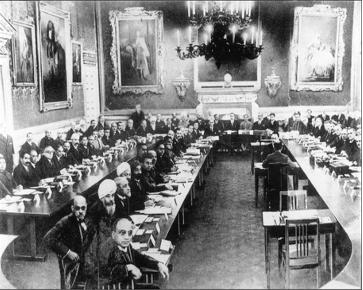

In 1927, a group called the Simon Commission was announced. Its job was to look at India's government and suggest changes. However, all the main Indian political groups, including the Indian National Congress, refused to work with the commission because it had no Indian members. This caused problems and led to more calls for India's independence.

The Irwin Declaration

In 1929, a new government came to power in Britain. Lord Irwin then made a big announcement called the Irwin Declaration. This statement promised that Britain would eventually give India dominion status. This meant India would become fully self-governing, like Canada or Australia. Many British politicians were upset by this, but it was a step towards India's independence.

However, Indian leaders felt it wasn't enough. Mahatma Gandhi then started a campaign of peaceful protest called the Salt Satyagraha. He walked for 24 days to the sea to make salt, breaking a government rule. Irwin had many Indian leaders, including Gandhi, put in jail. This made things worse, and unrest grew.

Agreement with Mahatma Gandhi

In 1931, Gandhi was released from prison. Lord Irwin invited him to meetings, and they talked eight times. Irwin found Gandhi very different but respected him.

These talks led to the Gandhi–Irwin Pact on March 5, 1931. In this agreement:

- The Indian National Congress would stop its protests.

- The Congress would join a meeting in London to discuss India's future.

- The British government would remove certain laws and release people jailed for non-violent protests.

Gandhi agreed to attend the Second Round Table Conference as the only representative of the Congress. Lord Irwin praised Gandhi's honesty and patriotism. However, shortly after, some Indian revolutionaries were executed, which caused more anger.

British Politics: 1931–1935

Lord Irwin returned to Britain in May 1931. He was given a special honor, the KG. He didn't take a new government job right away, saying he wanted to spend time at home.

In 1932, he became the President of the Board of Education again. In 1933, he was chosen as the Chancellor of Oxford University. In 1934, he inherited the title Viscount Halifax when his father passed away.

He helped create the Government of India Act 1935, a very important law about how India would be governed. In June 1935, he became the Secretary of State for War. He felt Britain was not ready for war but didn't push for more weapons. In November 1935, he became the Lord Privy Seal and the leader of the House of Lords.

Foreign Policy and World War II

Working with Anthony Eden

Halifax became very important in foreign affairs. He worked closely with Anthony Eden, who was the Foreign Secretary. They agreed that Germany's decision to re-arm its military was something Britain should accept, as it seemed like Germany was returning to normal after World War I.

In November 1937, Halifax visited Germany and met Adolf Hitler. This visit was seen as an attempt to talk with the German government. Halifax spoke about possible changes to Europe's borders, as long as they happened peacefully. He didn't object to Hitler's plans for Austria or parts of Czechoslovakia and Poland in principle.

In February 1938, Anthony Eden resigned as Foreign Secretary because he disagreed with Prime Minister Chamberlain's plans to make more deals with Benito Mussolini, the leader of Italy. Halifax was then appointed Foreign Secretary on February 21, 1938.

The Munich Agreement

When Hitler took over Austria in March 1938, Halifax became more convinced that Britain needed to re-arm its military. It was clear that Czechoslovakia was Hitler's next target. Britain and France felt they weren't strong enough to fight Germany.

Halifax stayed in London while Prime Minister Chamberlain flew to Germany to meet Hitler. At first, Halifax wanted to encourage Czechoslovakia to give in to Germany's demands. However, he soon realized that giving in too much was a bad idea.

On September 25, 1938, Halifax spoke against Hitler's demands after a second meeting between Hitler and Chamberlain. He helped convince the British government to reject Hitler's harsh terms. This brought Britain and Germany very close to war.

The Munich Agreement was eventually signed after a third meeting. It was popular at the time because it seemed to avoid war. But it also made Hitler more determined to destroy Czechoslovakia later. Halifax defended the agreement, saying it was the better of two bad choices.

After Munich, Halifax started to take a stronger stand against Germany. He pushed for Britain to re-arm and form stronger alliances to prevent more German aggression.

After Munich

Halifax advised Chamberlain not to call an early election after Munich. He was also disgusted by the violent attacks against Jewish people during Kristallnacht in November 1938. He wanted Britain to help countries in Eastern Europe financially to keep them from falling under Germany's control.

In January 1939, Halifax went with Chamberlain to Rome to talk with Mussolini. He also pushed for military talks with France because of the growing danger of war with Germany and Italy. After Hitler broke the Munich agreement and took over the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Halifax was a key person in changing Britain's policy. Chamberlain then announced that Britain would go to war to defend Poland.

Halifax gave a guarantee to Poland on March 31, 1939, hoping to send a clear message to Germany that there would be "no more Munichs."

Although he didn't like the Soviet government, Halifax realized that Britain should try to form an alliance with them. He said that Britain couldn't ignore a country with 180 million people. However, talks with the Soviets failed, and they signed an agreement with Germany instead in August 1939.

When Germany invaded Poland, Halifax refused any talks while German troops were still in Poland. Britain declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939.

The War Cabinet Crisis of May 1940

On May 8, 1940, Prime Minister Chamberlain's government faced a vote of no confidence because of problems in the war against Germany. The government won the vote, but by a small margin. This showed that Chamberlain had lost a lot of support.

On May 9, Chamberlain met with Halifax and Churchill. Churchill later wrote that Chamberlain tried to convince him that Halifax should be Prime Minister. But other accounts say Halifax quickly said he wasn't the right person for the job. Halifax felt that Churchill was better suited to lead the country during wartime. He also worried that if he became Prime Minister, he would just be a figurehead, with Churchill making all the important decisions about the war.

On May 10, the Labour Party agreed to join a new government, but only if Chamberlain was not the Prime Minister. So, Chamberlain resigned, and King George VI asked Churchill to form a new government. Churchill then created a smaller War Cabinet, keeping only Halifax and Chamberlain from the old government.

Churchill's position was not very strong at first. Many in his own party didn't like him. But Halifax had the support of most Conservatives and the King. Despite this, Halifax believed Churchill's energy and leadership were better for the country at that time. He also thought he could have more influence as Churchill's deputy.

Dunkirk and Peace Talks

On May 10, 1940, the same day Churchill became Prime Minister, Germany invaded Belgium, the Netherlands, and France. By May 22-23, the German army had trapped British forces at Dunkirk. Halifax believed Britain should try to negotiate a peace deal with Hitler, using Italy as a go-between. He thought this would help bring the British troops home. He didn't think Britain could realistically defeat Germany.

Churchill strongly disagreed. He believed that nations that fought on could recover, but those that surrendered were finished. He also felt the British people would never accept surrender.

Between May 25 and 28, Churchill and Halifax argued in the War Cabinet. It seemed Halifax might win, and Churchill could be forced out. Halifax almost resigned.

However, Churchill gathered his larger group of ministers and gave a powerful speech. He said Britain must fight on, no matter the cost. He convinced everyone that Britain had to keep fighting Hitler. Churchill also got the support of Neville Chamberlain.

Churchill told the War Cabinet that there would be no peace talks. Halifax had lost the argument. A few weeks later, Halifax rejected German peace offers.

Ambassador to the United States

When Chamberlain retired due to illness, Churchill offered Halifax a job as a kind of Deputy Prime Minister. But Halifax refused.

In December 1940, the British Ambassador to the United States suddenly died. Churchill told Halifax to take the job. Churchill believed this was a great chance for Halifax to help bring the United States into the war. Churchill thought Halifax's reputation from the appeasement policy meant he had no future in Britain.

Halifax sailed to the United States in January 1941. President Franklin D. Roosevelt personally welcomed him. At first, Halifax made some mistakes in public relations. For example, he asked about the timeline for a new law, which made some Americans think Britain was interfering in their politics.

Halifax was initially quiet in public. His relationship with Roosevelt was good, but Churchill often communicated directly with the President, which limited Halifax's role. However, Halifax soon became more effective. He toured the country and met many ordinary Americans. He became very popular after the attack on Pearl Harbor, which brought the US into the war.

Halifax grew tired of his job in Washington, especially after his middle son died in the war in November 1942, and his younger son was seriously wounded in January 1943. He asked to be relieved of his post in March 1943 but had to stay.

In May 1944, he was given the new title Earl of Halifax. He took part in many international meetings about the United Nations and the Soviet Union.

After the Labour Party won the election in July 1945, Halifax agreed to stay on as Ambassador until May 1946. In February 1946, he was present when Churchill gave his famous "Iron Curtain" speech. Halifax didn't fully agree with Churchill's strong views on the Soviet Union and urged him to be more friendly. He also helped negotiate an important loan from the US to Britain.

His time as Ambassador was challenging, as American power grew. But the partnership between Britain and the US during World War II was very successful.

Later Life

Back in the United Kingdom, Halifax chose not to rejoin the main Conservative Party leadership. He felt it wouldn't be right since he had been working for the Labour government. He supported the Labour government's plan for India to become fully independent.

In his retirement, he took on many honorary roles. He was the Chancellor of the Order of the Garter and the Chancellor of Oxford University. He was also the Chancellor of the University of Sheffield. He was the Master of the Middleton Hunt, a fox hunting group. From 1947, he was chairman of the General Advisory Council of the BBC.

By the mid-1950s, his health was declining. One of his last major speeches was in November 1956, where he criticized the government's actions during the Suez Crisis. He died of a heart attack at his home in Garrowby on December 23, 1959, at the age of 78.

Halifax was known for being very tall, standing at 6 feet 5 inches. He had a charming personality and the natural authority of someone from a noble family.

Styles

- April 16, 1881 – August 8, 1885: Edward Frederick Lindley Wood

- August 8, 1885 – February 10, 1910: The Hon. Edward Frederick Lindley Wood

- February 10, 1910 – October 25, 1922: The Hon. Edward Frederick Lindley Wood MP

- October 25, 1922 – December 22, 1925: The Rt. Hon. Edward Frederick Lindley Wood MP

- December 22, 1925 – April 3, 1926: The Rt. Hon. The Lord Irwin PC

- April 3, 1926 – April 18, 1931: His Excellency The Rt. Hon. The Lord Irwin PC, Viceroy and Governor-General of India

- April 18, 1931 – January 19, 1934: The Rt. Hon. The Lord Irwin PC

- January 19, 1934 – December 1940: The Rt. Hon. The Viscount Halifax PC

- December 1940 – 1944: His Excellency The Rt. Hon. The Viscount Halifax PC, HM Ambassador to the United States of America

- 1944–1946: His Excellency The Rt. Hon. The Earl of Halifax PC, HM Ambassador to the United States of America

- 1946–1959: The Rt. Hon. The Earl of Halifax PC

Honours

- Honours of Edward Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax

Marriage and Family

Halifax married Lady Dorothy Evelyn Augusta Onslow in 1909. She was the daughter of William Onslow, 4th Earl of Onslow, who had been a Governor-General of New Zealand.

They had five children:

- Lady Anne Dorothy Wood (born 1910)

- Lady Mary Agnes Wood (born and died 1910)

- Charles Ingram Courtenay Wood, 2nd Earl of Halifax (born 1912)

- Major Hon. Francis Hugh Peter Courtenay Wood (born 1916, died in action in 1942 during World War II)

- Richard Frederick Wood, Baron Holderness (born 1920)

Images for kids

-

Halifax and Winston Churchill in 1938. Notice Halifax's artificial left hand, hidden by a black glove.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |