Anglo-Irish trade war facts for kids

The Anglo-Irish Trade War (also called the Economic War) was a tough fight over trade between the Irish Free State (which is now Ireland) and the United Kingdom. It lasted from 1932 to 1938. The problem started because the Irish government stopped paying back loans to Britain. These loans had helped Irish farmers buy land many years before. This refusal led both countries to put special taxes on each other's goods, which really hurt the Irish economy.

This "war" was about two main things:

- How much independence the Irish Free State had from Britain.

- New economic plans in Ireland after the Great Depression (a time when economies around the world struggled).

Contents

Protecting Irish Businesses

When Éamon de Valera's new government, called Fianna Fáil, came to power in 1932, they wanted to protect Irish businesses. They started a policy called protectionism. This meant adding special taxes, called tariffs, on many imported goods, especially from Britain. Britain was the Free State's biggest trading partner.

The government believed this was important for a few reasons:

- To help new Irish industries grow.

- To reduce Ireland's strong reliance on Britain.

- To deal with the big drop in demand for Irish farm products because of the Great Depression, which began in 1929.

Seán Lemass, the minister for Industry and Commerce, led a strong effort to make the Free State self-sufficient. This meant producing enough food and goods for itself. People were encouraged to avoid British imports and to "Buy Irish Goods."

Stopping Land Annuity Payments

The Irish government also wanted to stop paying "land annuities" to Britain. These payments came from loans given to Irish tenant farmers by the Land Commission starting in the 1880s. These loans helped farmers buy land from their landlords.

In 1923, the previous Irish government had promised Britain that the Free State would keep paying these debts. However, in 1932, de Valera decided that the Free State would no longer pay them. His government passed the Land Act 1933, which allowed this money to be used for local projects in Ireland instead.

After many talks in 1932, discussions broke down. The two sides couldn't agree on who should decide if the payments were owed. De Valera also demanded that Britain:

- Pay back the £30 million already paid in land annuities.

- Pay the Irish Free State £400 million for supposedly overtaxing Ireland between 1801 and 1922.

The Conflict Gets Worse

To get the annuity money back, British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald put a 20% tax on Irish farm products coming into the UK. These products made up 90% of all Irish exports. Irish households were also unwilling to pay 20% extra for these food products.

The Irish Free State responded by putting similar taxes on British imports. For British coal, they even used a famous old slogan: "Burn everything English except their coal." While Britain was not affected as much, the Irish economy suffered greatly from this "Economic War."

Inside Ireland, the government still collected the annuities from its own farmers, which cost them over £4 million each year. Unemployment was very high, and the Great Depression made things worse. The government asked everyone to support the fight with Britain and share the hardship. Farmers were told to grow more crops to feed the home market.

The Economic War was very hard, especially for farmers. In 1935, a "Coal-Cattle Pact" helped a little. Britain agreed to buy a third more Irish cattle, and the Free State agreed to import more British coal. But the cattle industry was still in trouble. The government bought most of the extra beef and paid farmers to slaughter calves that couldn't be exported. They even started a "free beef for the poor" program.

Many farmers, especially large cattle breeders, faced huge problems. Like the "Land War" of the past century, they refused to pay their property taxes or land annuities. To get the payments, the government seized their livestock and quickly sold them at auctions for low prices. Farmers tried to stop these sales by blocking roads and railways. Police were called in to protect buyers, and some people were even killed.

With farmers having little money, people bought fewer manufactured goods, which hurt industries. New import taxes helped some Irish industries grow. Seán Lemass introduced the Control of Manufactures Act, which said that most of an Irish company had to be owned by Irish citizens. This caused some larger Irish companies, like Guinness, to move their main offices abroad. New sugar beet factories were opened in Mallow, Tuam, and Thurles.

The Economic War did not seriously affect the balance of trade between the two countries because imports from Britain were limited. However, British exporters were very unhappy because they lost business in Ireland. The pressure from British businesses and the unhappiness of Irish farmers pushed both sides to find a solution.

Changes to Irish Government and Laws

In 1933, de Valera removed the Oath of Allegiance. This oath required loyalty to the Free State Constitution and to George V as "King in Ireland." In late 1936, he used the Edward VIII abdication crisis (when the British king gave up his throne) to pass new laws. These laws ended the role of the Governor-General of the Irish Free State in Irish affairs.

From 1934 to 1936, the government was concerned about delays caused by the Senate (called Seanad Éireann in Irish). They passed a law to change it. The modern Seanad Éireann was created by the 1937 Constitution and first met in January 1939.

Even with the economic problems, de Valera's government remained popular. He called an election in 1933, before the worst effects of the war were felt. In the July 1937 election, his support dropped a little, but so did support for his main rival, the Fine Gael party. He stayed in power with the help of the Labour Party.

On the same day as the 1937 election, the Constitution of Ireland was approved by a public vote. This new Constitution moved the state even further away from the original Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921.

Ending the Economic War

In 1935, the tension between Britain and Ireland started to ease. With the 20% taxes, coal and cattle became very expensive. There was so much extra cattle in Ireland that farmers had to start slaughtering them because they couldn't be sold to the British.

Britain and Ireland then signed the Coal-Cattle Pact. This agreement made buying these goods cheaper and easier. The Coal-Cattle Pact showed that both sides wanted to end the Economic War.

The crisis ended after a series of talks in London between British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and de Valera. An agreement was made in 1938. Under the Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement, all the special taxes put in place over the past five years were removed.

Even though the Economic War caused a lot of suffering and financial loss for Ireland, its outcome was seen as good. Ireland could still put taxes on British imports to protect its new industries. The agreement also settled the £3 million-per-year land annuities debt with a single payment of £10 million to Britain. Both sides also agreed to drop all other claims against each other.

The agreement also included the return of the Treaty Ports to Ireland. These ports had been kept by Britain under the 1921 Treaty. When World War II started in 1939, having control of these ports allowed Ireland to remain neutral during the war.

Long-Term Effects

Protectionism, the policy of taxing imports to protect local industries, stayed a key part of Irish economic policy into the 1950s. This policy limited trade and caused many people to leave Ireland.

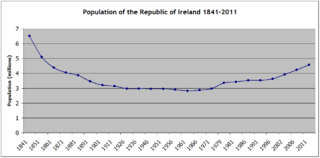

However, Seán Lemass, who first pushed for protectionism, later became known for ending it from 1960 onwards. He was advised by T. K. Whitaker's 1958 report, "First Programme for Economic Expansion." This change was important for Ireland's application to join the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in 1961, which it finally joined in 1973. The population of the Republic of Ireland started to grow in the late 1960s for the first time since the Free State was formed in 1922.