History of Ireland (1801–1923) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ireland

Éire (Irish)

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1801–1922 | |||||||||||

|

Flag of the Lord Lieutenant

|

|||||||||||

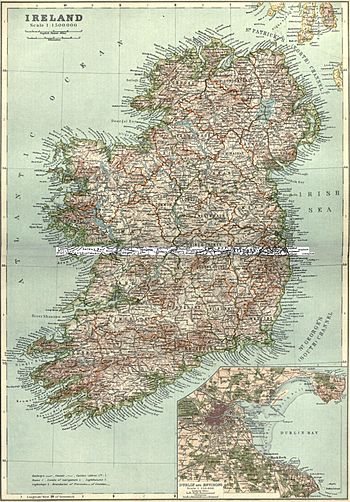

Map of Ireland in 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica eleventh edition

|

|||||||||||

| Status | Country of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland | ||||||||||

| Capital | Dublin | ||||||||||

| Largest city | Dublin (-1901) Belfast (1901-1922) |

||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||

| Religion |

|

||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Irish | ||||||||||

| Government | Division of a constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||

|

• 1801–1820 (first)

|

George III | ||||||||||

|

• 1910–1921 (last)

|

George V | ||||||||||

| Lord Lieutenant | |||||||||||

|

• 1801–1805 (first)

|

Philip Yorke | ||||||||||

|

• 1921 (last)

|

Edmund FitzAlan | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Imperial Britain | ||||||||||

|

• Acts of Union came into effect

|

1 January 1801 | ||||||||||

| 29 April 1916 | |||||||||||

|

• Government of Ireland Act enacted

|

3 May 1921 | ||||||||||

| 6 December 1921 | |||||||||||

|

• Irish Free State established

|

6 December 1922 | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1911 | 84,421 km2 (32,595 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

|

• 1911

|

4,390,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency |

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 1801 to 1922. During this time, the island was mostly controlled by the UK Parliament in London. This was done through a special government office in Dublin, called the Dublin Castle administration.

The 19th century was a tough time for Ireland. The Great Irish Famine in the 1840s caused a huge drop in population. Many people died or left the country. Later, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, there was a strong push for Home Rule. This meant Ireland would govern itself, but still be part of the UK.

Even though a law for Home Rule was passed, some people in Ireland, especially in Ulster, strongly opposed it. They were called unionists. When World War I started, the Home Rule plan was put on hold. By 1918, many Irish people wanted full independence, not just Home Rule. This led to a war between Irish independence fighters and the British government.

Eventually, talks between the main Irish party, Sinn Féin, and the UK government led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty. This treaty meant that most of Ireland became a new country, the Irish Free State (now the Republic of Ireland). Only the six northeastern counties, now called Northern Ireland, stayed part of the United Kingdom.

Contents

- Joining the United Kingdom: The Acts of Union

- The Great Famine: A Time of Hunger

- Young Irelander Rebellion

- Land Rights and Farmers' Struggles

- Irish Language and Culture

- The Home Rule Movement

- Workers' Rights and Strikes

- The Home Rule Crisis and World War I

- The Easter Rising

- The War of Independence

- The Irish Civil War

- Images for kids

- See also

Joining the United Kingdom: The Acts of Union

Ireland started the 19th century after a big rebellion in 1798. There was still some fighting and another small rebellion in 1803. The Acts of Union were created to make Ireland a part of Britain. This was meant to stop future rebellions and prevent other countries from using Ireland against Britain.

In 1800, both the Irish Parliament and the Parliament of Great Britain passed laws to join together. From January 1, 1801, the Irish Parliament was closed. The Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain became one country: the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

It took a lot of effort to get the Act passed in the Irish Parliament. Many members were given rewards and titles to agree to it. This was similar to how Scotland and England joined in 1707.

After the Union, Ireland was managed by British government officials. The main people were the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, who represented the King, and the Chief Secretary for Ireland. The Chief Secretary became more important over time. Irish politicians were elected to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom in London.

The British administration in Ireland was often called "Dublin Castle". It was mostly controlled by wealthy Anglo-Irish families until 1922.

Catholic Rights and Daniel O'Connell

Many Irish Catholics and Dissenters hoped the Union would end unfair laws against them. These laws, called Penal Laws, limited their rights. They also hoped for Catholic Emancipation, which would allow Catholics to hold public office. However, King George III refused to allow this.

An Irish Catholic lawyer named Daniel O'Connell started a campaign for Catholic Emancipation. He formed the Catholic Association. A famous soldier and statesman, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, who was Prime Minister, helped pass the law. He convinced King George IV to sign the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829. This law allowed British and Irish Catholics to be members of Parliament. Daniel O'Connell was the first Catholic to join Parliament since 1689.

O'Connell then led a campaign to undo the Act of Union and bring back Irish self-government. He used peaceful methods, like large public meetings, to show how much support he had. Even though he didn't get the Union repealed, his work led to important changes in local government and laws for the poor.

Despite O'Connell's peaceful approach, there was still some violence in Ireland. In Ulster, there were fights between Catholics and the Orange Order. In other areas, poor farmers fought against landlords and the government. Secret groups like the Whiteboys and Ribbonmen used violence to scare landlords into treating tenants better. The Tithe War in the 1830s was about Catholic farmers having to pay taxes to the Protestant Church of Ireland. The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) police force was set up to deal with this violence.

The Great Famine: A Time of Hunger

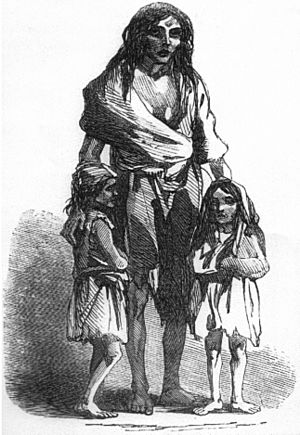

Ireland faced big economic challenges in the 19th century. The worst was the Great Irish Famine (1845–1851). About one million people died, and another million left the country.

Before the famine, many Irish people had very small farms. The population grew quickly, and farms were divided among sons, making them even smaller. People relied heavily on potatoes for food. Many landlords lived far away and didn't manage their estates well.

When potato blight (a plant disease) destroyed the potato crops in 1845, many rural families had no food. The British government's response was slow and not enough. Even though Ireland produced other food, much of it was sent to England. Public works projects were set up, but they couldn't help everyone. The situation became terrible when diseases like typhoid and cholera spread.

People around the world sent money to help. This included the Choctaw people in the US, former slaves in the Caribbean, and even Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. However, the government's actions were not enough, turning a bad situation into a disaster.

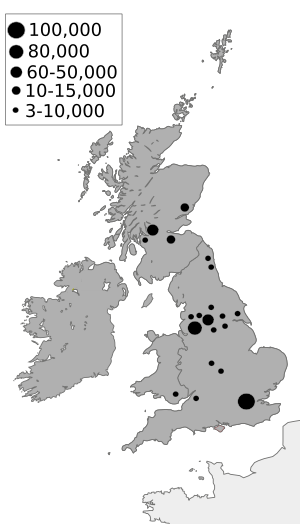

Many Irish people had already been leaving Ireland before the famine. But during the famine, emigration greatly increased. Many went to Great Britain, North America, and Australia. The large number of Irish people who moved to America, called the Irish American diaspora, later helped fund and encourage the Irish independence movement. In 1858, a secret group called the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), also known as the Fenians, was formed. They wanted to fight for Irish independence.

Young Irelander Rebellion

In 1848, some members of O'Connell's group, called the Young Irelanders, tried to start a rebellion against British rule. This happened during the worst years of the famine. The British military quickly stopped it. The leader, William Smith O'Brien, failed to capture a group of police. He and his friends were arrested and sent to Australia.

Land Rights and Farmers' Struggles

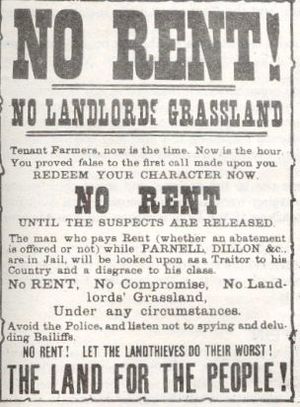

After the famine, many Irish farmers and workers had died or left. Those who stayed fought for better rights for tenant farmers. They also wanted land to be shared more fairly. This period was called the "Land War". It had both a nationalist and a social side. Most landlords in Ireland were Protestant settlers from England. Many Irish Catholics believed their land had been unfairly taken from their ancestors.

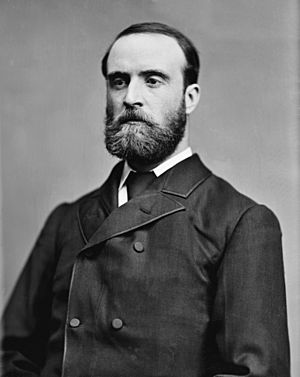

The Irish National Land League was formed to protect farmers' interests. They demanded "Fair rent, Free sale, and Fixity of tenure." This meant fair prices for rent, the right to sell their farm improvements, and secure tenancy. Leaders like Michael Davitt and Charles Stewart Parnell joined the movement.

The Land League's most effective tactic was the boycott. This is when people refuse to deal with someone they disagree with. Unpopular landlords were avoided by the local community. There was also violence against landlords and their property. The British government passed laws to control the violence. Leaders like Parnell were put in prison for a time.

Over time, new laws like the Landlord and Tenant (Ireland) Act 1870 and the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881 gave more rights to tenant farmers. Later, the Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903 allowed farmers to buy their land from landlords. These laws created many small landowners in the Irish countryside. This reduced the power of the old Anglo-Irish landowning class.

Irish Language and Culture

Irish culture changed a lot in the 19th century. After the Famine, the Irish language began to decline. This started in the 1830s when the first National Schools were set up. These schools taught only in English and did not allow Irish to be spoken.

The Famine hit the Irish-speaking areas the hardest, as these were often poor and rural. Many Irish speakers died or emigrated. By 1900, English was the main language in Ireland.

In response, Irish nationalists started a Gaelic revival in the late 1800s. They wanted to bring back the Irish language, literature, and sports. Groups like the Gaelic League and the Gaelic Athletic Association became very popular. However, most of their members spoke English, and the movement couldn't stop the decline of the Irish language.

The English spoken in Ireland, called Hiberno-English, became unique. It mixed older forms of English with Irish language structures. Famous Irish writers like J.M. Synge and George Bernard Shaw used this style.

The Home Rule Movement

Before the 1870s, most Irish politicians belonged to the main British parties. But in the 1870s, a new movement for Home Rule began. This movement wanted Ireland to govern itself as a region within the United Kingdom.

Charles Stewart Parnell became a strong leader of this movement. His party, the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), became very powerful in Irish politics. They won many seats in the British Parliament.

Two Home Rule bills were introduced by British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, but neither became law. Many people in England, especially in rural areas, did not support Home Rule for Ireland.

Home Rule also divided Ireland. Many Unionists, especially in Ulster, were against it. They worried that a Catholic-dominated Irish Parliament would treat them unfairly. Riots broke out in Belfast in 1886 when the first Home Rule Bill was discussed.

In 1889, a personal scandal involving Parnell split the Irish party. This weakened the Home Rule movement for a time. However, the party eventually reunited under John Redmond. After 1910, the Irish Parliamentary Party held the balance of power in the British Parliament.

In 1911, a new law reduced the power of the House of Lords to block bills. This meant a Home Rule Bill could finally pass. In 1912, a third Home Rule Bill was introduced. It passed in the House of Commons but was delayed by the House of Lords for two years. By 1914, the situation was tense. Both unionists and nationalists formed armed groups, leading to a crisis.

Workers' Rights and Strikes

While nationalism was a big issue, social and economic problems were also important in the early 1900s. Dublin had extreme poverty, with some of the worst slums in the British Empire.

Unemployment was high, and workers' pay and conditions were very poor. Socialist leaders like James Larkin and James Connolly started organizing trade unions. In 1907, Belfast saw a big strike by dockworkers. In Dublin, the Dublin Lockout of 1913 was an even bigger dispute. Over 20,000 workers were fired for joining Larkin's union. There was rioting, and some people died.

The labor movement was divided along nationalist lines. Southern unions were part of the Irish Trades Union Congress, while Ulster unions joined British ones. Mainstream Irish nationalists didn't like radical social ideas. However, some socialists found support among more extreme Irish Republicans. James Connolly formed the Irish Citizen Army in 1913 to protect striking workers. This group later took part in the Easter Rising in 1916.

The Home Rule Crisis and World War I

By early 1914, Ireland seemed close to civil war. Two private armies, one nationalist and one unionist, were ready to fight over Home Rule.

In 1912, 100,000 unionists formed the Ulster Volunteers to resist Home Rule. They later created the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). In 1914, they secretly brought in 30,000 German rifles. In response, Irish nationalists formed the Irish Volunteers to ensure Home Rule passed. They also brought in weapons.

In September 1914, as First World War began, the UK Parliament finally passed the Government of Ireland Act 1914. This law would give Ireland self-government. However, it was put on hold until after the war. To ensure Home Rule happened, nationalist leaders supported Ireland joining the British war effort. Many Irishmen joined the British Army.

Irish soldiers fought bravely and suffered huge losses in the war. Both sides hoped that after the war, Britain would support their goals. But the delay of Home Rule and Ireland's involvement in the war led some radical nationalists to plan an armed rebellion.

The Easter Rising

In Easter 1916, about 1500 republican rebels, including members of the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army, started a rebellion in Dublin. This was called the "Easter Rising". It was put down after a week of fighting.

At first, many Irish people condemned the Rising. But the British government's harsh response, including the executions of the rebel leaders, changed public opinion. People began to feel sympathy for the rebels.

The government and media wrongly blamed Sinn Féin for the rebellion. Sinn Féin was a small political party at the time. However, after the Rising, many survivors, like Éamon de Valera, joined Sinn Féin. They made the party's goal a fully independent Irish Republic.

In the December 1918 general election, Sinn Féin won 73 out of 105 seats in Ireland. The Sinn Féin politicians refused to sit in the British Parliament. Instead, on January 21, 1919, they met in Dublin and formed their own parliament, called Dáil Éireann. They declared an Irish Republic.

The War of Independence

For three years, from 1919 to 1921, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) fought a guerrilla war against the British Army and special police units. These police units were known as the Black and Tans and the Auxiliary Division. Both sides committed brutal acts. The Black and Tans burned towns and treated civilians very harshly. The IRA caused harm to many civilians they believed were helping the British. This conflict was called the Irish War of Independence or the Anglo-Irish War.

The war made Unionists in Ulster even more worried about an all-Ireland government. The British government still wanted to give Ireland self-government. They passed a new law, the Government of Ireland Act 1920. This law divided Ireland into two self-governing regions: Northern Ireland (six counties) and Southern Ireland (twenty-six counties). The Parliament of Northern Ireland was created in 1921. However, nationalists boycotted the government of Southern Ireland, so it never really worked.

In July 1921, a ceasefire was agreed. Talks between Irish and British leaders led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty. This treaty gave southern and western Ireland a special status, similar to Canada. It was more independence than had been offered before.

Northern Ireland was given the right to leave the new Irish Free State, which it immediately did. A special commission was set up to decide the final border. In 1925, the existing border was kept.

The Irish Civil War

The Second Dáil narrowly approved the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921. Under leaders like Michael Collins, the Irish Free State was set up. The pro-Treaty IRA became the new National Army, and a new police force, the Garda Síochána, was formed.

However, a strong group led by Éamon de Valera opposed the treaty. They believed it:

- Ended the Irish Republic declared in 1916.

- Required Irish politicians to swear an oath to the King.

- Accepted the division of Ireland.

De Valera and his supporters left the Dáil. The IRA also split. This led to a bloody Irish Civil War between those who supported the treaty and those who opposed it. The war ended in 1923, and many people were put to death. The Civil War caused more deaths than the War of Independence and created divisions that are still felt in Irish politics today.

Images for kids

See also

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |