History of the United Kingdom facts for kids

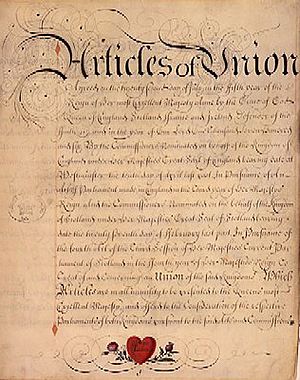

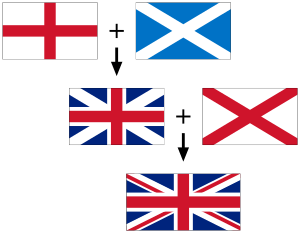

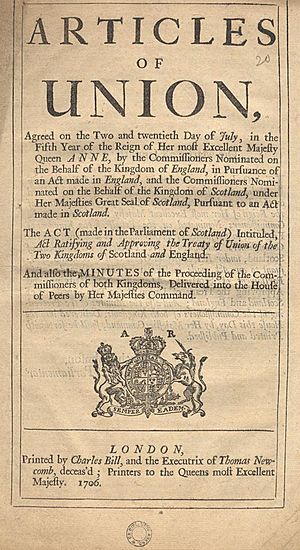

The history of the United Kingdom began in the early 1700s. It started with the Treaty of Union and Acts of Union in 1707. These agreements joined the kingdoms of England and Scotland. They formed a new country called Great Britain. One historian, Simon Schama, called this union "one of the most astonishing transformations in European history."

Later, in 1801, the Act of Union 1800 added the Kingdom of Ireland. This created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

The first years saw some rebellions, like the Jacobite risings. These ended with a defeat for the Stuart family at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. In 1763, Great Britain won the Seven Years' War. This led to the growth of the First British Empire.

Britain lost its 13 American colonies after being defeated by the United States, France, and Spain in the War of American Independence. After this, Britain built a Second British Empire in Asia and Africa. Because of this, British culture, its technology, and its way of governing spread worldwide.

A big event was the French Revolution and the wars with Napoleon from 1793 to 1815. British leaders saw this as a huge danger. They worked hard to form groups that finally defeated Napoleon in 1815. The Tories were in power from 1783 until 1830.

Later, ideas for reform, often from religious groups, led to changes. These changes allowed more people to vote and opened up the economy to free trade. Important leaders in the 1800s included Palmerston, Disraeli, Gladstone, and Salisbury.

The Victorian era was a time of wealth and strong middle-class values. Britain led the world economy and kept peace from 1815 to 1914. The First World War (1914–1918) saw Britain, allied with France, Russia, and the United States, fight a tough war against Germany. Britain helped create the League of Nations after the war.

Even though the Empire and London's financial markets were strong, Britain's industries started to fall behind Germany and the United States. People wanted peace so much that they supported trying to avoid war with Hitler's Germany in the late 1930s. But when Germany invaded Poland in 1939, the Second World War began. In this war, the Soviet Union and the U.S. joined Britain as main Allied powers.

After 1945, Britain was no longer a military or economic superpower. This was clear during the Suez Crisis in 1956. Britain could not afford its Empire anymore, so it gave independence to almost all its colonies. These new countries usually joined the Commonwealth of Nations.

The years after the war were hard. Financial help from the United States and Canada helped a lot. By the 1950s, things got better. From 1945 to 1950, the Labour Party created a welfare state. They took control of many industries and started the National Health Service.

Britain strongly opposed Communist expansion after 1945. It played a big part in the Cold War and helped form NATO. NATO is a powerful military alliance with West Germany, France, the U.S., Canada, and other countries. The UK has also been a leading member of the United Nations since it started.

In the 1990s, new economic ideas led to private companies taking over nationalized industries. London's role as a global financial center grew. Also in the 1990s, movements in Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales led to more local decision-making.

Britain's relationship with Western Europe has changed over time. It joined the European Economic Community in 1973, which changed its economic ties with the Commonwealth. However, the Brexit vote in 2016 meant the UK would leave the European Union, which it did in 2020.

In 1922, Catholic Ireland became the Irish Free State. A day later, Northern Ireland left the Free State and rejoined the United Kingdom. In 1927, the UK officially changed its name to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. It is often called Britain or the United Kingdom (or UK).

Contents

Forming the United Kingdom

Birth of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain was created on May 1, 1707. This happened when the Kingdom of England (which included Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland joined together. The details of this union were agreed upon in the Treaty of Union the year before. Then, the parliaments of Scotland and England approved the treaty through their own Acts of Union.

England and Scotland had shared a monarch since 1603. That's when James VI of Scotland also became James I of England after Queen Elizabeth I died without children. This event was called the Union of the Crowns. More than a hundred years later, the Treaty of Union combined the two kingdoms into one. Their two parliaments became a single parliament of Great Britain.

Queen Anne, who was ruling at the time, wanted the two kingdoms to be more closely linked. She became the first monarch of Great Britain. The union was important for England's safety. Scotland gave up the right to choose a different monarch after Anne's death. It also gave up the right to make its own alliances with European countries. This meant no European power could use Scotland to invade England.

Even though it was now one kingdom, some things stayed separate. Scottish and English law remained different. The Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the Anglican Church of England also stayed separate. England and Scotland also kept their own education systems.

The creation of Great Britain happened during the War of the Spanish Succession. In this war, Queen Anne continued the fight against France that William III had started. The Duke of Marlborough won big victories against the French. The war ended with the treaties of Utrecht and Rastadt in 1713–1714.

Hanoverian Kings Rule Britain

Queen Anne died in 1714. George Louis, the Elector of Hanover, became King George I (1714–1727). He focused more on Hanover and had many German advisors, which made him unpopular. However, he did make the army stronger and created a more stable political system in Britain. He also helped bring peace to northern Europe.

Groups who wanted the Stuart family back on the throne were still strong. They started a revolt in 1715–1716. The son of James II planned to invade England. But before he could, John Erskine, Earl of Mar, launched an invasion from Scotland, which was easily defeated.

George II (1727–1760) made the government system more stable. Sir Robert Walpole led the government from 1730–42. George II helped build the first British Empire. He made the colonies in the Caribbean and North America stronger. Working with Prussia, Britain defeated France in the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). This victory gave Britain full control of Canada.

George III ruled from 1760–1820. He was born in Britain and spoke English as his first language. He is often seen by Americans as the reason for the American War of Independence. He faced health challenges after 1788, and his eldest son acted as regent. George III was the last king to have a strong influence on government. His long reign is known for losing the first British Empire in the American Revolutionary War (1783). France helped the Americans to get revenge for its defeat in the Seven Years' War.

His reign also saw the start of a second empire in India, Asia, and Africa. The Industrial Revolution began, making Britain an economic powerhouse. Most importantly, there was a long struggle with the French. This included the French Revolutionary Wars (1793–1802) and the huge Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), which ended with Napoleon's defeat.

Warfare and Money

From 1700 to 1850, Britain was involved in many wars and rebellions. It had a large and expensive Royal Navy and a small army. When more soldiers were needed, Britain hired fighters from other countries or paid allies to fight. The rising costs of war meant the government had to find new ways to get money. It started relying on customs and excise taxes, and after 1790, an income tax.

Working with bankers, the government borrowed large sums during wartime and paid them back in peacetime. Taxes rose to 20% of the national income. The demand for war supplies helped the industrial sector grow, especially for naval supplies, weapons, and textiles. This gave Britain an advantage in international trade after the wars.

The French Revolution in the 1790s divided British political opinion. Conservatives were shocked by the killing of the king and the violence. Britain was at war with France almost constantly from 1793 until Napoleon's final defeat in 1815. Conservatives warned that radical ideas could cause chaos in British society. This anti-French Revolution feeling was strongest among the wealthy landowners and upper classes.

British Empire Grows

The Seven Years' War, which started in 1756, was the first global war. It was fought in Europe, India, North America, the Caribbean, and Africa. The Treaty of Paris (1763) had big effects on Britain and its empire. In North America, France lost its future as a colonial power. It gave New France to Britain and Louisiana to Spain. Spain gave Florida to Britain. In India, Britain defeated France, leaving Britain in control of India's future. Britain's victory made it the world's leading colonial power.

In the 1760s and 1770s, relations between the Thirteen Colonies and Britain became difficult. This was mainly because people in the colonies opposed Parliament's attempts to tax them without their agreement. Disagreements turned into violence, and in 1775, the American Revolutionary War began. In 1776, the Americans declared their independence. After capturing a British army in 1777, the U.S. allied with France (and Spain helped France). This balanced the military power. The British army only controlled a few coastal cities.

By 1780–81, things were tough for Britain. Taxes were high, and the war in America seemed endless. The Gordon Riots broke out in London in 1781. In October 1781, Lord Cornwallis surrendered his army at Yorktown, Virginia. The Treaty of Paris (1783) was signed in 1783, officially ending the war and recognizing the United States' independence.

Losing the Thirteen Colonies, which were Britain's most populated colonies, marked a change. Britain shifted its focus to Asia, the Pacific, and later Africa. Adam Smith's book Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, argued that colonies were not essential. He said that free trade should replace the old policies that had focused on protecting trade. The growth of trade between the new United States and Britain after 1783 showed that political control was not needed for economic success.

For its first 100 years, the British East India Company focused on trade in India. But in the 1700s, as the Mughal Empire weakened, the Company started to focus on gaining territory. The British, led by Robert Clive, defeated the French and their Indian allies in the Battle of Plassey. This gave the Company control of Bengal and made it a major military and political power in India. Over the next decades, it slowly took control of more land, either directly or through local rulers who were under British influence. The Indian Army, which was 80% native Indian sepoys, helped with this.

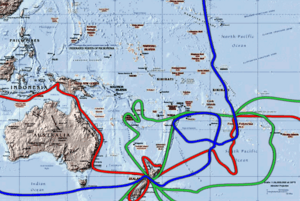

On August 22, 1770, James Cook discovered the eastern coast of Australia during a scientific voyage to the South Pacific. In 1778, Joseph Banks, Cook's botanist, told the government that Botany Bay was suitable for a penal settlement. In 1787, the first group of convicts sailed there, arriving in 1788.

Britain had mixed feelings about the French Revolution starting in 1789. When war broke out in Europe in 1792, Britain stayed neutral at first. But in January 1793, King Louis XVI was executed. This, along with France threatening to invade the Netherlands, pushed Britain to declare war. For the next 23 years, the two nations were almost constantly at war, except for a short break in 1802–1803. Britain was the only European nation that never gave in to or allied with France.

At the start of the 1800s, Britain faced a new challenge from France under Napoleon. This struggle was different from past wars. It was a fight between two ideas: Britain's constitutional monarchy versus the French Revolution's liberal ideas, which Napoleon's empire claimed to support. Napoleon even threatened to invade Britain itself.

Britain in the 1800s

Joining with Ireland

On January 1, 1801, Great Britain and Ireland joined to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

The events leading to this union had been going on for centuries. Invasions from England by the Normans starting in 1170 led to many conflicts in Ireland. English kings tried to conquer and control the whole island. In the early 1600s, many Protestant settlers from Scotland and England moved to Ireland, especially in Ulster. This displaced many native Roman Catholic Irish people.

After the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Irish Roman Catholics were not allowed to vote or attend the Irish Parliament. The new English Protestant rulers were known as the Protestant Ascendancy. By the late 1700s, the all-Protestant Irish Parliament gained more independence from the British Parliament. Under the Penal Laws, no Irish Catholic could be in the Irish Parliament. This was despite about 90% of Ireland's population being native Irish Catholic when these bans started in 1691. These laws disadvantaged Catholics and, to a lesser extent, Protestant dissenters.

In 1798, many dissenters joined with Catholics in a rebellion. It was inspired and led by the Society of United Irishmen. They wanted to create a fully independent Ireland with a republican government. Despite help from France, the Irish Rebellion of 1798 was put down by British forces.

Inspired by the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), a group of Irish volunteers pushed for more independence for the Irish Parliament. This was granted in 1782, giving Ireland free trade and law-making independence. However, the French Revolution encouraged more calls for reform. The Society of United Irishmen, made up of Presbyterians from Belfast and both Anglicans and Catholics in Dublin, wanted to end British control. Their leader, Theobald Wolfe Tone, worked with the Catholic Convention in 1792 to demand an end to the penal laws. When he couldn't get support from the British government, he went to Paris. He encouraged French naval forces to land in Ireland to help with planned uprisings. These uprisings were crushed by government forces. These rebellions convinced British Prime Minister William Pitt that the only solution was to end Irish independence.

The union of Great Britain and Ireland was made official by the Act of Union 1800. This created the "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland". The Act was passed by both the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland. The Irish Parliament was controlled by the Protestant Ascendancy and did not represent the country's Roman Catholic population. Many votes were gained through what some called bribery, like giving out peerages and honours to those who opposed the union.

Under the merger, the separate Parliaments of Great Britain and Ireland were ended. They were replaced by a single Parliament of the United Kingdom. Ireland became a part of the United Kingdom. It sent about 100 Members of Parliament (MPs) to the House of Commons in Westminster. It also sent 28 representative peers to the House of Lords, chosen by Irish peers. However, Roman Catholic peers were not allowed to sit in the Lords.

Part of the deal for Irish Catholics was supposed to be Catholic Emancipation. This would have removed many restrictions on Catholics. However, King George III blocked it. He said that freeing Roman Catholics would break his Coronation Oath. The Roman Catholic leaders had supported the Union. But blocking Catholic Emancipation greatly weakened the Union's appeal.

Napoleonic Wars

During the War of the Second Coalition (1799–1801), Britain took control of most French and Dutch colonies. However, many British troops died from tropical diseases. When the Treaty of Amiens ended the war, Britain had to return most of the colonies. This peace was only a short break. Napoleon continued to challenge Britain by trying to stop its trade and by taking over Hanover. In May 1803, war started again.

Napoleon's plans to invade Britain failed because his navy was weaker. In 1805, Lord Nelson's fleet decisively defeated the French and Spanish at Trafalgar. This was the last major naval battle of the Napoleonic Wars.

These naval and colonial conflicts were similar to earlier European wars. Battles in the Caribbean and taking colonial bases could affect the war in Europe. Historians later called the Napoleonic conflict a "world war" because it was so widespread, like the Seven Years' War.

In 1806, Napoleon issued the Berlin Decrees, starting the Continental System. This policy aimed to weaken Britain's economy by closing French-controlled areas to British trade. The British army was a small threat to France. Britain's army was only 220,000 at its peak, while France had a million men.

The Royal Navy stopped France's trade outside Europe. But it could not stop France's trade with other European countries. France's population and farms were much larger than Britain's. Many in the French government thought isolating Britain from Europe would end its economic power. But the Continental System never worked. Britain had the biggest industrial capacity in Europe. Its control of the seas allowed it to build great economic strength through trade with its growing new Empire. Britain's strong navy meant France could never have the peace needed to control Europe. It also could not threaten Britain or its main colonies.

The Spanish uprising in 1808 finally allowed Britain to get a foothold in Europe. The Duke of Wellington and his army slowly pushed the French out of Spain. In early 1814, as Napoleon was being pushed back in the east, Wellington invaded southern France. After Napoleon surrendered and was sent to Elba, peace seemed to return. But when he escaped in 1815, Britain and its allies had to fight him again. Wellington's and Von Blucher's armies defeated Napoleon for good at Waterloo.

Paying for the War

A key reason for British success was its ability to use its industries and money to defeat France. Britain had a population of 16 million, barely half of France's 30 million. France had more soldiers, but Britain paid for many Austrian and Russian soldiers. In 1813, Britain paid for about 450,000 allied soldiers. Most importantly, British production stayed strong. Businesses sent products to where the military needed them. Smuggling goods into Europe hurt French efforts to ruin the British economy.

The British budget in 1814 reached £66 million. This included £10 million for the Navy, £40 million for the Army, £10 million for allies, and £38 million for interest on the national debt. The national debt grew to £679 million, more than double the country's total yearly output. Hundreds of thousands of investors and taxpayers supported this, despite higher taxes. The total cost of the war was £831 million. In contrast, France's money system was not good. Napoleon's forces often had to take supplies from conquered lands.

Napoleon also tried to hurt Britain's economy. His Berlin Decree of 1806 stopped British goods from entering European countries allied with France. All connections were to be cut, even mail. But British merchants smuggled in many goods. The Continental System was not a strong economic weapon. It did some damage to Britain, especially in 1808 and 1811. But Britain's control of the oceans helped. It hurt France and its allies more, as they lost a good trading partner. Angry governments started to ignore the Continental System, which weakened Napoleon's alliances.

War of 1812 with the United States

At the same time as the Napoleonic Wars, trade arguments and Britain forcing American sailors into its navy led to the War of 1812 with the United States. Americans called it the "second war of independence." But in Britain, it was barely noticed, as all attention was on the fight with France. Britain could send few resources to this conflict until Napoleon fell in 1814. American frigates also caused some embarrassing defeats for the British navy, which lacked enough sailors due to the war in Europe.

A stronger war effort in 1814 brought some successes, like the burning of Washington. But many important people, like the Duke of Wellington, said that a full victory over the U.S. was impossible. Peace was agreed to at the end of 1814. But Andrew Jackson, not knowing this, won a big victory over the British at the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815. News took weeks to cross the Atlantic before steamships. The Treaty of Ghent ended the war in February 1815. The main result was the permanent defeat of the Native American allies Britain had relied on. The U.S.-Canada border became peaceful, and trade restarted.

Kings George IV and William IV

Britain was very different after the Napoleonic Wars than it was in 1793. As industries grew, society changed. More people lived in cities and fewer in the countryside. The years after the war saw an economic downturn. Bad harvests and rising prices caused widespread social unrest. Europe after 1815 was worried about new revolutions. Even in Britain, laws were passed in 1819 to stop radical activities. By the late 1820s, the economy improved, and many of these strict laws were removed. In 1828, new laws gave civil rights to religious dissenters.

George IV was a weak ruler as regent (1811–20) and king (1820–30). He let his ministers handle government affairs. It became clear that the king would accept as prime minister whoever had the most support in the House of Commons. His governments oversaw the victory in the Napoleonic Wars and tried to deal with the social and economic problems that followed. His brother William IV ruled (1830–37) but was not very involved in politics. His reign saw several reforms: the poor law was updated, child labour was limited, slavery was abolished in almost all the British Empire, and the Reform Act 1832 changed the British voting system.

There were no major wars until the Crimean War of 1853–56. While other European monarchies tried to stop new ideas, Britain accepted them. Britain helped a constitutional government in Portugal in 1826. It also recognized the independence of Spain's American colonies in 1824. British merchants, bankers, and later railway builders played big roles in the economies of most Latin American countries. In 1827, the British helped the Greeks, who were fighting for independence from the Ottoman Empire.

Whig Reforms of the 1830s

The Whig Party became strong again by supporting moral reforms. These included changing the voting system, ending slavery, and giving rights to Catholics. Catholic emancipation was achieved in the Catholic Relief Act of 1829. This removed most major restrictions on Roman Catholics in Britain.

The Whigs became strong supporters of Parliament reform. They made Lord Grey prime minister from 1830–1834. The Reform Act of 1832 was their most important achievement. It allowed more people to vote and ended the system of "rotten boroughs" and "pocket boroughs." These were places where powerful families controlled elections. Instead, power was shared based on population. This added 217,000 voters to the 435,000 in England and Wales.

The main effect of the act was to weaken the power of wealthy landowners. It increased the power of middle-class professionals and business owners. For the first time, they had a significant voice in Parliament. However, most manual workers, clerks, and farmers did not own enough property to vote. The aristocracy still controlled the government, the Army, the Royal Navy, and high society. After investigations showed the terrible conditions of child labor, limited reforms were passed in 1833.

Chartism started after the 1832 Reform Bill did not give working-class people the right to vote. Activists said the working class had been "betrayed." In 1838, Chartists issued the People's Charter. It demanded that all men could vote, equal election districts, secret ballots, payment for MPs (so poor men could serve), yearly Parliaments, and no property requirements to be an MP. Leaders saw the movement as extreme, so the Chartists could not force big changes to the constitution. Historians see Chartism as both a continuation of the 1700s fight against corruption and a new step in demands for democracy in an industrial society.

In 1832, Parliament abolished slavery in the Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. The government bought the slaves for £20,000,000 (the money went to rich plantation owners, mostly in England). The slaves were freed, especially those on the Caribbean sugar islands.

Victorian Era: 1837–1901

Victoria became queen in 1837 at age 18. Her long reign until 1901 saw Britain reach its peak of economic and political power. Exciting new technologies appeared, like steamships, railroads, photography, and telegraphs. These made the world much faster. Britain mostly stayed out of European politics and was not affected by the revolutions in 1848. The Victorian era saw the second British Empire grow.

Historians often call the mid-Victorian era (1850–1870) Britain's 'Golden Years'. There was peace and wealth, as national income per person grew by half. Much of this wealth came from growing industries, especially textiles and machinery. It also came from a worldwide network of trade and engineering. There was peace abroad (except for the short Crimean War, 1854–56) and social peace at home. The Chartist movement, a working-class movement for democracy, ended in 1848. Its leaders moved to other activities, like trade unions. The working class ignored foreign activists and joined in celebrating the new wealth. Employers often looked after their workers and generally accepted trade unions. Companies provided welfare services, from housing and schools to libraries and gyms. Middle-class reformers tried to help working classes adopt middle-class values.

There was a feeling of freedom, as people felt they were free. Taxes were very low, and government rules were minimal. There were still problems, like occasional riots, especially those against Catholics. Society was still ruled by the aristocracy and gentry. They controlled high government offices, both houses of Parliament, the church, and the military. Becoming a rich businessman was not as respected as inheriting a title and owning land. Literature was doing well, but fine arts were not as strong. The Great Exhibition of 1851 showed Britain's industrial strength, not its art or music. The education system was not great, and universities (outside Scotland) were also not top-notch.

Historian Llewellyn Woodward said that England was a better country in 1879 than in 1815. He noted that things were fairer for the weak, women, children, and the poor. There was more movement and less of the feeling that fate controlled everything. Public awareness was higher, and freedom meant more than just political limits. However, he also said that England in 1871 was not perfect. Housing and living conditions for the working class in towns and the countryside were still a disgrace.

Foreign Policy and Empire

Free Trade and Global Influence

The Great London Exhibition of 1851 clearly showed Britain's leadership in engineering and industry. This lasted until the United States and Germany grew stronger in the 1890s. Using free trade and financial investments, Britain had a big influence on many countries outside Europe, especially in Latin America and Asia. So, Britain had a formal Empire (where it ruled directly) and an informal one (based on the power of the British pound).

Russia, France, and the Ottoman Empire

A constant worry was the possible collapse of the Ottoman Empire. It was understood that this would lead to a fight for its land and possibly war for Britain. To prevent this, Britain tried to stop the Russians from taking Constantinople and the Bosporus Straits. It also wanted to stop Russia from threatening India through Afghanistan. In 1853, Britain and France joined the Crimean War against Russia. Despite some poor leadership, they captured the Russian port of Sevastopol. This forced Tsar Alexander II to ask for peace.

A second war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire in 1877 led to another European intervention. This time, it was at the negotiating table. The Congress of Berlin stopped Russia from forcing a harsh treaty on the Ottoman Empire. Despite its alliance with France in the Crimean War, Britain did not fully trust the Second Empire of Napoleon III. This was especially true as the emperor built strong warships and became more active in foreign policy. But after Napoleon's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, he was allowed to live his last years in exile in Britain.

American Civil War

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), British leaders personally disliked American republicanism. They favored the more aristocratic Confederacy, which was a major source of cotton for British textile mills. Prince Albert helped calm a war scare in late 1861. The British people, who relied heavily on American food imports, generally supported the United States. The small amount of cotton available came from New York, as the U.S. Navy's blockade stopped 95% of Southern exports to Britain.

In September 1862, during the Confederate invasion of Maryland, Britain (along with France) thought about stepping in to negotiate a peace. This would have meant war with the United States. But in the same month, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation. Since supporting the Confederacy now meant supporting slavery, European countries no longer had a reason to intervene.

Meanwhile, the British sold weapons to both sides. They built ships to run the blockade for profitable trade with the Confederacy. They also secretly allowed warships to be built for the Confederacy. These warships caused a major diplomatic argument that was settled in the Alabama Claims in 1872, in America's favor.

Empire Continues to Grow

In 1867, Britain united most of its North American colonies as the Dominion of Canada. This gave Canada self-government and control over its internal affairs. Britain handled foreign policy and defense.

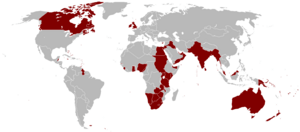

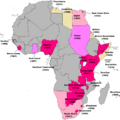

The second half of the 1800s saw a huge expansion of Britain's colonial empire in Asia. In the "Scramble for Africa," Britain aimed to have the Union Jack flag flying from "Cairo to Cape Town." Britain defended its empire with the world's strongest navy and a small professional army. It was the only power in Europe that did not force people into military service.

The rise of the German Empire after 1871 created a new challenge. Germany (along with the United States) threatened to take Britain's place as the world's top industrial power. Germany gained some colonies in Africa and the Pacific. But Chancellor Otto von Bismarck managed to keep general peace through his balance of power strategy. When William II became emperor in 1888, he removed Bismarck. He started using aggressive language and planned to build a navy to rival Britain's.

Boer War

Ever since Britain took control of South Africa from the Netherlands during the Napoleonic Wars, it had problems with the Dutch settlers. These settlers moved further away and created two republics of their own. The British wanted to control these new countries. The Dutch-speaking "Boers" (or "Afrikaners") fought back in the War in 1899–1902.

The Boers were outmatched by a mighty empire. They fought a guerrilla war, which was difficult for the British regular soldiers. But Britain's larger numbers, better equipment, and often harsh tactics eventually led to a British victory. The war was costly in terms of human rights and was widely criticized by Liberals in Britain and around the world. However, the United States supported Britain. The Boer republics were joined into the Union of South Africa in 1910. It had its own government but its foreign policy was controlled by London. It was a key part of the British Empire.

The difficulty in defeating the Boers had several effects in Britain. Militarily, it was clear that earlier army reforms were not enough. A plan to create a general staff to control military operations had been put aside. It took five more years to set up a general staff and other army reforms. The Royal Navy was now threatened by Germany's fast growth and advanced technology. Britain responded with a huge shipbuilding program started in 1904. This included the HMS Dreadnought in 1906. It was the first modern battleship with new armor, propulsion, and guns. It made all other warships old-fashioned.

The war showed that Britain was not loved around the world. It had more enemies than friends. Its policy of "splendid isolation" (having no formal allies) was risky. Britain needed new friends. It made a military alliance with Japan and settled old disagreements to build a close relationship with the United States.

Ireland and Home Rule

Part of the agreement for the 1800 Act of Union said that the Penal Laws in Ireland would be removed and Catholic Emancipation would be granted. However, King George III blocked emancipation. He argued that granting it would break his coronation oath to defend the Anglican Church. A campaign led by lawyer and politician Daniel O'Connell, and the death of George III, led to Catholic Emancipation in 1829. This allowed Catholics to sit in Parliament. O'Connell then tried, but failed, to get the Act of Union repealed.

When potato blight hit Ireland in 1846, many rural people had no food. Relief efforts were not enough, and hundreds of thousands died in the Great Hunger. Millions more moved to England or North America. Ireland's population became permanently smaller.

Isaac Butt started a new moderate nationalist movement, the Home Rule League, in the 1870s. It became the Irish Parliamentary Party. This party was a major political force under William Shaw and a young Protestant landowner, Charles Stewart Parnell. It controlled Irish politics, from conservative landowners to the Land League, which wanted big changes to how land was owned in Ireland.

Parnell's movement campaigned for 'Home Rule'. This meant Ireland would govern itself as a region within the United Kingdom. This was different from O'Connell, who wanted complete independence but with a shared monarch. Two Home Rule Bills (1886 and 1893) were introduced by Liberal Prime Minister Gladstone, but neither became law.

The issue divided Ireland. A significant unionist minority (mostly in Ulster) opposed Home Rule. They feared that a Catholic-Nationalist parliament in Dublin would treat them unfairly and put taxes on industry. While most of Ireland was farming, six counties in Ulster had heavy industry. Parliament passed laws in 1870, 1881, 1903, and 1909 that allowed most tenant farmers to buy their land and lowered rents for others.

Early 1900s

Edwardian Era: 1901–1914

Queen Victoria died in 1901, and her son Edward VII became king. This started the Edwardian Era. It was known for big displays of wealth, unlike the more serious Victorian Era. At the start of the 1900s, things like motion pictures, cars, and airplanes were becoming common. The new century felt very hopeful. Social reforms from the last century continued, and the Labour Party was formed in 1900.

Edward died in 1910, and George V became king (1910–36). George V was a popular king who worked hard and avoided scandals. He and Queen Mary set the example for modern British royalty, based on middle-class values. He understood the Empire better than his prime ministers. He used his excellent memory for details to connect with his people.

The era was prosperous, but political problems were growing. Historians noted a "strange death of liberal England" as several crises hit at once in 1910–1914. These included serious social and political instability from the Irish crisis, labor unrest, women's suffrage movements, and political fights in Parliament. At one point, it seemed the Army might refuse orders about Northern Ireland. No solution was in sight when the unexpected start of the Great War in 1914 put domestic issues on hold.

World War I: 1914–1918

Britain entered the war because it supported France, which supported Russia, which supported Serbia. Even more important, Britain was determined to keep its promise to defend Belgium. Britain was loosely part of the Triple Entente with France and Russia. They fought against the Central Powers of Germany, Austria, and the Ottoman Empire. After a few weeks, the Western Front became a deadly place where millions died, but no army made big advances.

The stalemate meant an endless need for men and supplies. By 1916, fewer people were volunteering. The government started conscription (forcing people to join the military) in Britain (but not in Ireland) to keep the Army strong. After a difficult start with industry, Britain replaced Prime Minister Asquith in December 1916 with the more energetic Liberal leader David Lloyd George. The nation successfully used its manpower, womanpower, industry, money, Empire, and diplomacy, with France and the U.S., to defeat the enemy.

After defeating Russia, the Germans tried to win in the spring of 1918 before millions of American soldiers arrived. They failed and were overwhelmed. They finally accepted an Armistice in November 1918, which was like a surrender.

Britain strongly supported the war. But in Ireland, Catholics were restless and planned a rebellion in 1916. It failed, but the harsh way the British put it down turned many against Britain. The economy grew about 14% from 1914 to 1918, even with so many men in the military. In contrast, the German economy shrank 27%. The war saw less civilian spending, with a lot of money going to weapons. The government's share of the country's total output jumped from 8% in 1913 to 38% in 1918. The war forced Britain to use up its financial savings and borrow large amounts from New York banks. After the U.S. entered in April 1917, Britain borrowed directly from the U.S. government.

The Royal Navy controlled the seas. It defeated the smaller German fleet in the only major naval battle of the war, the Battle of Jutland in 1916. Germany was blockaded, leading to food shortages. Germany's navy increasingly used U-Boats to attack British ships. This risked war with the powerful neutral United States. The waters around Britain were declared a war zone where any ship was a target. After the liner Lusitania was sunk in May 1915, killing over 100 American passengers, U.S. protests made Germany stop unrestricted submarine warfare.

With victory over Russia in 1917, Germany thought it could finally have more soldiers on the Western Front. Planning a huge spring attack in 1918, it started sinking all merchant ships without warning again. The U.S. entered the war with the Allies. It provided the money and supplies needed to keep the Allies fighting. The U-boat threat was finally defeated by using a convoy system across the Atlantic.

On other fronts, the British, French, Australians, and Japanese took Germany's colonies. Britain fought the Ottoman Empire, suffering defeats in the Gallipoli Campaign and in Mesopotamia. It also encouraged Arabs to help drive the Turks from their lands. Tiredness and war-weariness grew worse in 1917, as the fighting in France continued with no end in sight. The German spring attacks of 1918 failed. With American soldiers arriving at 10,000 per day in the summer, the Germans realized they were being overwhelmed. Germany agreed to surrender on November 11, 1918.

Victorian ideas that continued into the early 1900s changed during World War I. The army had not been a large employer before the war. But by 1918, about five million people were in the army and the new Royal Air Force. The almost three million casualties were known as the "lost generation." Such numbers deeply affected society.

After the War

Britain and its allies won the war, but at a terrible human and financial cost. This created a feeling that wars should never be fought again. The League of Nations was founded to help nations solve problems peacefully, but these hopes were not fully met. The harsh peace terms forced on Germany made it bitter and wanting revenge.

At the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, Lloyd George, American President Woodrow Wilson, and French premier Georges Clemenceau made the big decisions. They formed the League of Nations to prevent future wars. They divided up the losing countries to form new nations in Europe. They also divided up German colonies and Ottoman lands outside Turkey. They made Germany declare its guilt for starting the war. This policy caused deep anger in Germany and helped lead to movements like Nazism. Britain gained the German colony of Tanganyika and part of Togoland in Africa. Its dominions gained other colonies. Britain also gained control over Palestine and Iraq. Iraq became fully independent in 1932. Egypt, which Britain had controlled since 1882, became independent in 1922, though the British stayed there until 1952.

Irish Independence and Division

In 1912, the House of Lords delayed a Home Rule bill passed by the House of Commons. It became law as the Government of Ireland Act 1914. During these two years, there was a threat of religious civil war in Ireland. The Unionist Ulster Volunteers opposed the Act, and their nationalist rivals, the Irish Volunteers, supported it. The start of World War I in 1914 put the crisis on hold.

A disorganized Easter Rising in 1916 was brutally put down by the British. This made Catholics demand independence even more. Prime Minister David Lloyd George failed to introduce Home Rule in 1918. In the December 1918 General Election, Sinn Féin won most Irish seats. Its MPs refused to go to Westminster. Instead, they sat in the First Dáil parliament in Dublin. A declaration of independence was approved by Dáil Éireann, the self-declared Republic's parliament, in January 1919.

An Anglo-Irish War was fought between British forces and the Irish Republican Army from January 1919 to June 1921. The war ended with the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. This treaty created the Irish Free State. Six northern, mostly Protestant counties became Northern Ireland. They have remained part of the United Kingdom ever since, despite demands from the Catholic minority to join the Republic of Ireland. Britain officially adopted the name "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland" by the Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act 1927.

Between the World Wars

Historian Arthur Marwick believes that World War I caused a big change in British society. He says it swept away many old ideas and created a more equal society. He argues that the famous literary sadness of the 1920s was wrong. He says there were many good long-term effects of the war on British society. He points to workers becoming more aware of their rights, which quickly built up the Labour Party. He also notes that some women gained the right to vote, and there was faster social reform and more government control of the economy. Marwick says that class differences became less strict, national unity increased, and British society became more equal.

Popular Culture and Leisure

As people had more free time, could read more, had more money, and could travel more easily after 1900, there was more interest in leisure activities for everyone. The yearly vacation became common. Tourists flocked to seaside resorts; Blackpool had 7 million visitors a year in the 1930s. Organized leisure was mainly for men, with middle-class women joining in sometimes. More ordinary English people took part in sports and other activities, and their interest in watching sports grew a lot.

By the 1920s, cinema and radio attracted huge numbers of people of all classes, ages, and genders, with young women leading the way. Working-class men watched football loudly, sang along at music halls, gambled on horse racing, and took their families to Blackpool in summer. Political activists complained that working-class leisure distracted men from wanting revolution.

Cinema and Radio

The British film industry started in the 1890s. It built on London's strong theater reputation for actors and directors. The problem was that the American market was much larger and richer. It attracted top talent, especially when Hollywood became important in the 1920s. Hollywood produced over 80% of the world's films. Efforts to compete failed. The government set a quota for British films, but it didn't work. Hollywood also controlled the profitable Canadian and Australian markets. Bollywood (in Bombay) controlled the huge Indian market. The most famous directors left in London were Alexander Korda and Alfred Hitchcock. There was a creative boost from 1933-45, especially with Jewish filmmakers and actors escaping the Nazis. Meanwhile, huge cinemas were built for the large audiences who wanted to see Hollywood films. In Liverpool, 40% of the population went to one of the 69 cinemas once a week; 25% went twice. Traditionalists complained about American culture, but its long-term impact was small.

For radio, British audiences only had the BBC, a government agency that controlled broadcasting. John Reith, a very moral engineer, was in charge. His goal was to broadcast "All that is best in every department of human knowledge." He wanted to keep a "high moral tone." Reith successfully stopped an American-style free-for-all radio system that aimed for the biggest audiences and advertising money. The BBC had no paid advertising; all its money came from a tax on radio sets. Educated audiences enjoyed it greatly. While American, Australian, and Canadian stations had huge audiences cheering for local teams, the BBC focused on serving a national audience, not regional ones. Boat races, tennis, and horse racing were covered well. But the BBC was hesitant to spend its limited air time on long football or cricket games, no matter how popular they were.

Sports

The British showed a deep interest in many sports. They valued sportsmanship and fair play. Cricket became a symbol of the Imperial spirit across the Empire. Football became very popular with urban working classes, bringing noisy fans to sports. In some sports, there was debate about keeping amateur purity, especially in rugby and rowing. New games became popular quickly, including golf, lawn tennis, cycling, and hockey. Women were much more likely to play these new sports than the older ones. The aristocracy and wealthy landowners controlled hunting, shooting, fishing, and horse racing.

Cricket became well-known among the English upper class in the 1700s. It was a major part of sports competition in public schools. Army units across the Empire had free time and encouraged locals to learn cricket so they could have fun competitions. Most of the Empire adopted cricket, except for Canada. Cricket test matches (international games) started by the 1870s. The most famous is between Australia and England for "The Ashes."

For sports to become fully professional, coaching had to come first. Coaching slowly became professional in the Victorian era and was well established by 1914. In World War I, military units looked for coaches to oversee physical training and build team morale.

Reading Habits

As more people could read and had more free time after 1900, reading became a popular hobby. New adult fiction books doubled in the 1920s, reaching 2800 new books a year by 1935. Libraries tripled their book collections and saw high demand for new fiction. A big change was the cheap paperback book, started by Allen Lane at Penguin Books in 1935. The first titles included novels by Ernest Hemingway and Agatha Christie. They were sold cheaply (usually sixpence) in many inexpensive stores. Penguin aimed for an educated middle-class audience. It avoided the low-class image of American paperbacks. The books suggested cultural self-improvement and political education. The more political Penguin Specials, often with a left-wing view, were widely given out during World War II. However, the war years caused a shortage of staff for publishers and bookstores. There was also a severe shortage of rationed paper. This was made worse by an air raid on Paternoster Square in 1940 that burned 5 million books in warehouses.

Romantic fiction was especially popular, with Mills and Boon being the main publisher. Adventure magazines became very popular, especially those published by DC Thomson. The publisher sent people around the country to talk to boys and learn what they wanted to read. The stories in magazines and movies that boys liked most were about the exciting and just heroism of British soldiers fighting wars.

Politics and Economy in the 1920s

Growing the Welfare State

Two major programs that greatly expanded the welfare state were passed in 1919 and 1920 with little debate, even though Conservatives controlled Parliament. The Housing and Town Planning Act of 1919 set up a system of government housing. This followed the 1918 election promise of "homes fit for heroes." The Addison Act, named after the first Minister of Health, required local authorities to check their housing needs and start building houses to replace slums. The government paid for low rents. In England and Wales, 214,000 houses were built. The Ministry of Health became largely a ministry of housing.

The Unemployment Insurance Act of 1920 was passed when there was very little unemployment. It set up the "dole" system, which provided 39 weeks of unemployment benefits to almost all working people, except domestic servants, farm workers, and civil servants. Funded partly by weekly payments from both employers and employees, it gave weekly payments of 15 shillings for unemployed men and 12 shillings for unemployed women. Historian Charles Mowat called these two laws "Socialism by the back door." He noted how surprised politicians were when the costs to the government soared during the high unemployment of 1921.

Conservative Control

The Lloyd-George government ended in 1922. Stanley Baldwin, as leader of the Conservative Party (1923–37) and Prime Minister (in 1923–24, 1924–29, and 1935–37), was a dominant figure in British politics. His mix of strong social reforms and stable government was a powerful election strategy. As a result, the Conservatives governed Britain either alone or as the main part of the National Government. He was the last party leader to win over 50% of the vote (in the general election of 1931).

Baldwin's political plan was to make voters choose between the Conservatives on the right and the Labour Party on the left, pushing out the Liberals in the middle. This division happened. While the Liberals remained active, they won few seats and were a minor force until they joined a coalition with the Conservatives in 2010. Baldwin's reputation was high in the 1920s and 1930s. But it fell after 1945 as he was blamed for policies that tried to avoid war with Germany. Since the 1970s, Baldwin's reputation has improved somewhat.

Labour won the 1923 election, but in 1924, Baldwin and the Conservatives returned with a large majority.

Economy of the 1920s

Taxes rose sharply during the war and never returned to their old levels. A rich man paid 8% of his income in taxes before the war, and about a third afterwards. Much of the money went for the "dole," the weekly unemployment benefits. About 5% of the national income each year was transferred from the rich to the poor. Historian A.J.P. Taylor argued that most people "were enjoying a richer life than any previously known in the history of the world: longer holidays, shorter hours, higher real wages."

The British economy was slow in the 1920s. There were sharp declines and high unemployment in heavy industry and coal, especially in Scotland and Wales. Exports of coal and steel fell by half by 1939. Businesses were slow to adopt new ways of working from the U.S., like mass production and consumer credit. For over a century, the shipping industry had led world trade, but it struggled despite government efforts. With the very sharp drop in world trade after 1929, its situation became critical.

Chancellor of the Exchequer Winston Churchill put Britain back on the gold standard in 1925. Many economists blame this for the economy's poor performance. Others point to other factors, including the rising prices from the World War and problems caused by shorter working hours after the war.

By the late 1920s, the economy had stabilized. But the overall situation was disappointing, as Britain had fallen behind the United States as the leading industrial power. There was also a strong economic divide between the north and south of England. The south and Midlands were fairly prosperous by the 1930s. But parts of south Wales and the industrial north became known as "distressed areas" due to very high unemployment and poverty. Despite this, the standard of living continued to improve. Local councils built new houses for families moved from old slums. These new homes had modern facilities like indoor toilets, bathrooms, and electric lighting. The private sector also saw a house-building boom in the 1930s.

Labour and Strikes

During the war, trade unions were encouraged. Their membership grew from 4.1 million in 1914 to 6.5 million in 1918. They peaked at 8.3 million in 1920 before falling to 5.4 million in 1923.

Coal mining was a struggling industry. The best coal seams were running out, raising costs. Demand fell as oil started replacing coal for fuel. The 1926 general strike was a nine-day nationwide walkout. 1.3 million railwaymen, transport workers, printers, dockers, and steelworkers supported 1.2 million coal miners. The miners had been locked out by owners who demanded longer hours and less pay due to falling prices. The Conservative government had given a nine-month subsidy in 1925, but it was not enough to fix the struggling industry.

To support the miners, the Trades Union Congress (TUC), a group of all trade unions, called out certain key unions. They hoped the government would step in to reorganize the industry and increase the subsidy. The Conservative government had stored supplies, and essential services continued with middle-class volunteers. All three major parties opposed the strike. Labour Party leaders did not approve. They feared it would make the party seem too radical. The general strike itself was mostly peaceful. But the miners' lockout continued, and there was violence in Scotland. It was the only general strike in British history. TUC leaders like Ernest Bevin thought it was a mistake. Most historians see it as a unique event with few long-term effects. But Martin Pugh says it sped up working-class voters moving to the Labour Party, leading to future gains. The Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act 1927 made general strikes illegal. It also stopped unions from automatically paying money to the Labour Party. That act was mostly removed in 1946. The coal industry used up the easier-to-reach coal as costs rose. Output fell from 2567 million tons in 1924 to 183 million in 1945. The Labour government took control of the mines in 1947.

Great Depression

The Great Depression started in the United States in late 1929 and quickly spread worldwide. Britain had not experienced the economic boom of the 1920s like the U.S., Germany, Canada, and Australia. So, its economic downturn seemed less severe. Britain's world trade fell by half (1929–33). The output of heavy industry fell by a third. Employment and profits dropped in almost all areas. At its worst in summer 1932, 3.5 million people were officially unemployed, and many more had only part-time jobs.

Experts tried to stay positive. John Maynard Keynes, who had not predicted the slump, said, "There will be no serious direct consequences in London. We find the look ahead decidedly encouraging."

People who predicted doom, like Sidney and Beatrice Webb, repeated their warnings about capitalism's end. Now, more people listened. Starting in 1935, the Left Book Club offered a new warning every month. This made Soviet-style socialism seem more believable as an alternative.

The north of England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales were hit hardest by economic problems. Unemployment reached 70% in some areas in the early 1930s (with over 3 million out of work nationally). Many families relied entirely on payments from local government, known as the "dole."

In 1936, when unemployment was lower, 200 unemployed men marched from Jarrow to London. This highly publicized march aimed to show the struggles of the industrial poor. Although often romanticized by the Left, the Jarrow Crusade showed a deep split in the Labour Party and led to no government action. Unemployment remained high until the war created many jobs. George Orwell's book The Road to Wigan Pier describes the hardships of that time.

Appeasement and War

Strong memories of the horrors and deaths of World War I made Britain and its leaders want peace in the years between the wars. The challenge came from dictators, first Benito Mussolini of Italy, then Adolf Hitler of a much more powerful Nazi Germany. The League of Nations disappointed its supporters. It could not solve any of the threats from the dictators. British policy was to "appease" them, hoping they would be satisfied.

By 1938, it was clear that war was coming. Germany had the world's most powerful military. The final act of appeasement happened when Britain and France allowed Hitler to take Czechoslovakia at the Munich Agreement of 1938. Instead of being satisfied, Hitler threatened Poland. Finally, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain stopped appeasement and promised to defend Poland. However, Hitler made a deal with Joseph Stalin to divide Eastern Europe. When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Britain and France declared war. The British Commonwealth followed Britain's lead.

Second World War: 1939–1945

Britain, along with its dominions and the rest of the Empire, declared war on Nazi Germany in 1939 after Germany invaded Poland. After a quiet period called the "phoney war", the French and British armies collapsed under German attack in spring 1940. The British managed to rescue its main army from Dunkirk, but left all their equipment behind. Winston Churchill became Prime Minister, promising to fight the Germans to the very end.

The Germans threatened an invasion, which the Royal Navy was ready to stop. First, the Germans tried to control the air but were defeated by the Royal Air Force in the Battle of Britain in late summer 1940. Japan declared war in December 1941. It quickly took Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore, and Burma, and threatened Australia and India. Britain allied with the Soviet Union (starting in 1941) and had very close ties to the United States (starting in 1940).

The war was very expensive. It was paid for by high taxes, selling off assets, and accepting large amounts of Lend-Lease aid from the U.S. and Canada. The U.S. gave $40 billion in supplies. Canada also gave aid. (This American and Canadian aid did not have to be repaid, but there were also American loans that were repaid.)

Welfare State During War

Living conditions, especially regarding food, improved during the war. The government imposed rationing and paid for some food prices. Housing conditions worsened due to bombing, and clothing was in short supply.

Equality increased greatly. Incomes for the wealthy and white-collar workers dropped sharply as their taxes soared. Blue-collar workers benefited from rationing and price controls.

People demanded a bigger welfare state as a reward for their wartime sacrifices. This goal was outlined in a famous report by William Beveridge. It suggested that various income support services, which had grown bit by bit since 1911, should be made systematic and available to everyone. Unemployment and sickness benefits would be for everyone. There would be new benefits for maternity. The old-age pension system would be updated and expanded, requiring people to retire. A full National Health Service would provide free medical care for everyone. All major parties supported these ideas, and they were largely put into effect after the war.

The Royal Family's Role

The media called it a "people's war." This term caught on and showed the public's desire for planning and a bigger welfare state. The Royal family played important symbolic roles in the war. They refused to leave London during the Blitz (German bombing raids). They tirelessly visited troops, factories, shipyards, and hospitals across the country. Princess Elizabeth joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), a part of the army, and repaired trucks and jeeps. All social classes appreciated how the royals shared the hopes, fears, and hardships of the people.

After the War: 1945–Present

Britain won the war, but it lost India in 1947 and almost all the rest of its Empire by 1960. It discussed its role in world affairs. It joined the United Nations in 1945 and NATO in 1949, becoming a close ally of the United States. Prosperity returned in the 1950s. London remained a world center of finance and culture, but Britain was no longer a major world power. In 1973, after a long debate, it joined the European Union.

Austerity and Nationalization: 1945–1950

The end of the war saw a huge victory for Clement Attlee and the Labour Party. They were elected on a promise of greater social justice. Their policies included creating a National Health Service, building more council housing, and nationalizing major industries. Britain faced severe financial problems. It responded by reducing its international responsibilities and sharing the difficulties of an "age of austerity." Large loans from the United States and Marshall Plan grants helped rebuild and modernize its infrastructure and businesses.

Rationing and conscription continued into the postwar years. The country suffered one of the worst winters on record. However, events like the marriage of Princess Elizabeth in 1947 and the Festival of Britain boosted morale.

Nationalization of Industries

Labour Party experts found that there were no detailed plans for nationalization. The leaders realized they had to act fast to keep the momentum from the 1945 election victory. They started with the Bank of England, civil aviation, coal, and communications. Then came railways, canals, road transport, electricity, and gas. Finally, iron and steel were nationalized, which was special because it was a manufacturing industry. In total, about one-fifth of the economy was nationalized. Labour dropped its plans to nationalize farmlands.

The process used was developed by Herbert Morrison. He followed the model of public corporations already in place, like the BBC (1927). Owners of company stock were given government bonds, and the government took full ownership of each company, combining it into a national monopoly. The management stayed the same, but now they worked for the government. For the Labour Party leaders, nationalization was a way to control economic planning. It was not designed to modernize old industries or make them more efficient. There was no money for modernization. However, the Marshall Plan, run by American planners, did force many British businesses to adopt modern management methods.

Old socialists were disappointed. The nationalized industries seemed the same as the old private companies. Government financial problems made national planning almost impossible. Socialism was in place, but it did not seem to make a big difference. Workers had long supported Labour because of stories of mistreatment by managers. The managers were the same people as before, with similar power in the workplace. There was no worker control of industry. Unions resisted government efforts to set wages. By the time of the general elections in 1950 and 1951, Labour rarely boasted about nationalizing industry. Instead, Conservatives criticized the inefficiency and promised to reverse the takeover of steel and trucking.

Postwar Prosperity

As the country entered the 1950s, rebuilding continued. Immigrants from the remaining British Empire, mostly the Caribbean and the Indian subcontinent, were invited to help rebuild. As the 1950s went on, Britain lost its place as a superpower and could no longer keep its large Empire. This led to decolonization, and Britain withdrew from almost all its colonies by 1970. Events like the Suez Crisis showed that the UK's standing in the world had fallen.

The 1950s and 1960s were, however, relatively prosperous times after World War II. They saw the start of Britain's modernization, with the building of its first motorways. Also, in the 1960s, a great cultural movement began that spread worldwide. Unemployment was relatively low, and the standard of living continued to rise. More new private and council housing was built, and the number of slum properties decreased.

The postwar period also saw a big rise in the average standard of living. Average real wages increased by 40% from 1950 to 1965. Earnings for men in industry rose by 95% between 1951 and 1964. During the same time, the official workweek was shortened, and income tax was cut five times. People in traditionally low-paid jobs saw a particularly big improvement in their wages and living standards. As summarized by R. J. Unstead: "Opportunities in life, if not equal, were distributed much more fairly than ever before and the weekly wage-earner, in particular, had gained standards of living that would have been almost unbelievable in the thirties."

In 1950, the UK's standard of living was higher than in any EEC country except Belgium. It was 50% higher than West Germany's and twice as high as Italy's. However, by the early 1970s, the UK's standard of living was lower than all EEC countries except Italy. In 1951, the average weekly earnings for men over 21 were £8 6s 0d. A decade later, they nearly doubled to £15 7s 0d. By 1966, average weekly earnings were £20 6s 0d. Between 1964 and 1968, the percentage of households with a television rose from 80.5% to 85.5%. Washing machines rose from 54% to 63%, refrigerators from 35% to 55%, cars from 38% to 49%, telephones from 21.5% to 28%, and central heating from 13% to 23%.

Between 1951 and 1963, wages rose by 72% while prices rose by 45%. This allowed people to buy more consumer goods than ever before. Between 1955 and 1967, the average earnings of weekly-paid workers increased by 96% and salaried workers by 95%. Prices rose by about 45% in the same period. The growing wealth of the 1950s and 1960s was supported by steady full employment and a big rise in workers' wages. In 1950, the average weekly wage was £6 8s, compared with £11 2s 6d in 1959. As a result of wage rises, consumer spending also increased by about 20% during this period, while economic growth remained at about 3%. In addition, food rationing ended in 1954, and rules on buying on credit were relaxed in the same year. Because of these changes, many working-class people could buy consumer goods for the first time.

By 1963, 82% of all private households had a television, 72% a vacuum cleaner, 45% a washing machine, and 30% a refrigerator. Also, ownership of such items had spread down the social scale, and the gap between professional and manual workers had narrowed a lot.

The availability of household amenities steadily improved in the second half of the 1900s. From 1971 to 1983, households with their own fixed bath or shower rose from 88% to 97%. Those with an internal toilet rose from 87% to 97%. Also, the number of households with central heating almost doubled in that same period, from 34% to 64%. By 1983, 94% of all households had a refrigerator, 81% a color television, 80% a washing machine, 57% a deep freezer, and 28% a tumble-drier.

However, between 1950 and 1970, Britain was overtaken by most European Common Market countries in terms of telephones, refrigerators, television sets, cars, and washing machines per 100 people. Although the British standard of living was increasing, the standard of living in other countries increased faster. By 1967, Britain had fallen to eighth place among OECD countries in national income per person.

In 1976, UK wages were among the lowest in Western Europe. Also, while educational opportunities for working-class people had grown significantly since World War II, some developed countries surpassed Britain in education. By the early 1980s, about 80% to 90% of school leavers in France and West Germany received vocational training, compared with 40% in the United Kingdom. By the mid-1980s, over 80% of students in the United States and West Germany and over 90% in Japan stayed in education until age eighteen, compared with barely 33% of British students.

Empire to Commonwealth

Britain's control over its Empire became looser between the wars. Nationalism grew stronger in other parts of the empire, especially in India and Egypt.

Between 1867 and 1910, the UK gave "Dominion" status to Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. This meant they had almost complete self-rule within the Empire. They became founding members of the British Commonwealth of Nations (now called the Commonwealth of Nations since 1949). This is an informal but close group that replaced the British Empire. Starting with the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947, most of the rest of the British Empire was dismantled. Today, most of Britain's former colonies belong to the Commonwealth, almost all as independent members. However, there are 13 former British colonies, including Bermuda, Gibraltar, and the Falkland Islands. These have chosen to remain under London's rule and are known as British Overseas Territories.

The Troubles to Peace in Northern Ireland

In the 1960s, the moderate unionist Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Terence O'Neill, tried to reform the system. He wanted to give a greater voice to Catholics, who made up 40% of Northern Ireland's population. His goals were blocked by militant Protestants led by the Rev. Ian Paisley. Growing pressure from nationalists for reform and from unionists to resist reform led to the civil rights movement. Clashes grew out of control as the army struggled to contain the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the Ulster Defence Association.

British leaders feared that withdrawing would lead to widespread community conflict and many refugees. London shut down Northern Ireland's parliament and started direct rule. By the 1990s, the IRA's campaign had failed to gain wide public support or achieve its goal of British withdrawal. This led to negotiations that resulted in the 'Good Friday Agreement' in 1998. It gained popular support and largely ended the Troubles.

Economy in the Late 1900s

After the good times of the 1950s and 1960s, the UK faced extreme industrial problems and stagflation (high inflation and high unemployment) through the 1970s. This followed a global economic downturn. Labour had returned to government in 1964 under Harold Wilson, ending 13 years of Conservative rule. The Conservatives were restored to government in 1970 under Edward Heath, who failed to stop the country's economic decline. He was removed in 1974 as Labour returned to power under Harold Wilson. The economic crisis worsened after Wilson's return, and things did not get much better under his successor James Callaghan.

A strict modernization of the economy began under the controversial Conservative leader Margaret Thatcher. She became prime minister in 1979. This period saw record unemployment as deindustrialization ended many of the country's manufacturing industries. But it was also a time of economic boom as stock markets became more open and state-owned industries became privatized. Her rise to power was seen as the end of the time when the British economy was called the "sick man" of Western Europe. Inflation also fell during this period, and trade union power was reduced.

However, the miners' strike of 1984–1985 led to the end of most of the UK's coal mining. The use of North Sea gas and oil brought in a lot of tax and export money to help the new economic boom. This was also when the IRA brought the issue of Northern Ireland to Great Britain, carrying out a long bombing campaign on the British mainland.

After the economic boom of the 1980s, there was a short but severe recession between 1990 and 1992. This followed the economic chaos of Black Wednesday under the government of John Major, who had replaced Margaret Thatcher in 1990. However, the rest of the 1990s saw the start of a period of continuous economic growth that lasted over 16 years. This growth greatly expanded under the New Labour government of Tony Blair after his huge election victory in 1997. His party had changed its views, abandoning policies like nuclear disarmament and nationalization of key industries, and not reversing Thatcher's union reforms.

From 1964 until 1996, income per person had doubled. Ownership of various household goods had increased significantly. By 1996, two-thirds of households owned cars, 82% had central heating, most people owned a VCR, and one in five houses had a home computer. In 1971, 9% of households had no access to a shower or bathroom. This dropped to only 1% in 1990, mostly due to older properties being demolished or modernized. In 1971, only 35% had central heating, while 78% had it in 1990. By 1990, 93% of households had color television, 87% had telephones, 86% had washing machines, 80% had deep-freezers, 60% had video-recorders, and 47% had microwave ovens. Holiday entitlements also became more generous. In 1990, nine out of ten full-time manual workers were entitled to more than four weeks of paid holiday a year. Twenty years earlier, only two-thirds had been allowed three weeks or more. The postwar period also saw big improvements in housing conditions. In 1960, 14% of British households had no inside toilet, while in 1967, 22% of all homes had no basic hot water supply. By the 1990s, almost all homes had these amenities, along with central heating, which was a luxury just two decades before. From 1996/97 to 2006/07, real average household income increased by 20%. There has also been a shift towards a service-based economy. In 2006, 11% of working people were employed in manufacturing, compared with 25% in 1971.

Joining the European Community and Union

Britain's desire to join the Common Market (as the European Economic Community was known) was first stated in July 1961 by the Macmillan government. It was blocked in 1963 by French President Charles de Gaulle. After some hesitation, Harold Wilson's Labour Government applied for Britain to join the European Community (as it was now called) in May 1967. Like the first, this application was also blocked by de Gaulle.

In 1973, after DeGaulle was no longer president, Conservative Prime Minister Heath negotiated terms for admission. Britain finally joined the Community. The Labour Party, while in opposition, was deeply divided on the issue. However, its Leader, Harold Wilson, still supported joining. In the 1974 General Election, the Labour Party promised to renegotiate Britain's membership terms and then hold a referendum on whether to stay in the EC under the new terms. This was a new constitutional process in British history. In the referendum campaign, government members were free to express their views on either side of the question. A referendum was held on June 5, 1975, and the proposal to continue membership passed with a large majority.

The Single European Act (SEA) was the first major change to the 1957 Treaty of Rome. In 1987, the Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher made it law in the UK.

The Maastricht Treaty changed the European Community into the European Union. In 1992, the Conservative government under John Major approved it, despite opposition from some of his own party members.

The Treaty of Lisbon brought many changes to the Union's treaties. Key changes included more qualified majority voting in the Council of Ministers. It also increased the European Parliament's involvement in making laws. It removed the pillar system and created a President of the European Council and a High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. The Treaty of Lisbon also made the Union's human rights charter, the Charter of Fundamental Rights, legally binding. The Lisbon Treaty also increased the UK's voting power in the Council of the European Union from 8.4% to 12.4%. In July 2008, the Labour government under Gordon Brown approved the treaty, and the Queen ratified it.

Devolution for Scotland and Wales

On September 11, 1997, a referendum was held in Scotland. It asked if a devolved Scottish Parliament should be established. This resulted in a huge 'yes' vote for both establishing the parliament and giving it limited tax-changing powers. One week later, a referendum in Wales on establishing a Welsh Assembly was also approved, but with a very small majority. The first elections were held, and these bodies began to operate in 1999. The creation of these bodies has increased the differences between the Countries of the United Kingdom, especially in areas like healthcare. It has also brought up the "West Lothian question." This is a complaint that devolution for Scotland and Wales but not England means that all MPs in the UK parliament can vote on matters affecting England alone. But on those same matters, Scotland and Wales can make their own decisions.

21st Century

Wars and Terrorist Attacks

In the 2001 General Election, the Labour Party won a second time. However, voter turnout dropped to the lowest level in over 80 years. Later that year, the September 11th attacks in the United States led to American President George W. Bush starting the War on Terror. This began with the invasion of Afghanistan with British troops in October 2001.

Later, as the U.S. focused on Iraq, Tony Blair convinced Labour and Conservative MPs to vote to support the invasion of Iraq in 2003. This was despite huge anti-war marches in London and Glasgow. Forty-six thousand British troops, one-third of the Army's land forces, were sent to help with the invasion of Iraq. After that, British armed forces were responsible for security in southern Iraq. All British forces were withdrawn in 2010.

The Labour Party won the 2005 general election and a third term in a row.

Nationalist Government in Scotland