Brexit facts for kids

Brexit is a word made from "Britain" and "Exit." It means when the United Kingdom (UK) left the European Union (EU). The UK officially left the EU at 11:00 PM on 31 January 2020.

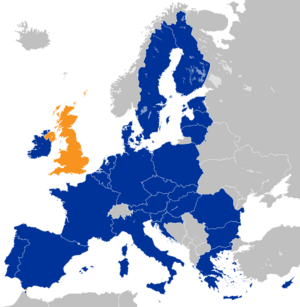

The UK joined the EU's earlier group, the European Communities (EC), on 1 January 1973. It is the only country to have left the EU. After Brexit, EU laws and the EU's main court no longer have power over British laws. However, the UK still follows many agreements it has with other countries, including EU countries.

Groups in the UK who did not like the EU, called "Eurosceptics," had always existed. In 1975, the UK held a public vote (a referendum) asking if people wanted to stay in the EC. Most people, 67.2%, voted to stay.

Years later, in the mid-2010s, the UK Independence Party (UKIP) became more popular. This led the Prime Minister, David Cameron, to promise another referendum on staying in the EU. This vote happened on 23 June 2016. People who wanted to stay were called "Remain," and those who wanted to leave were called "Leave."

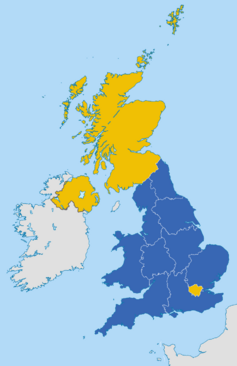

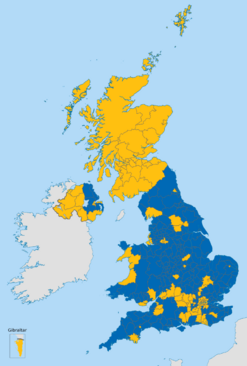

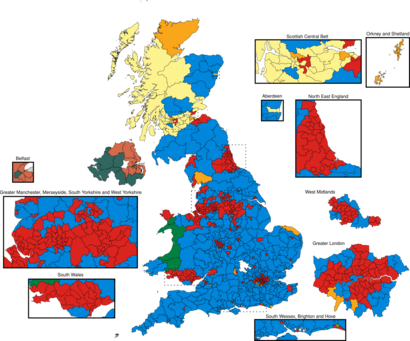

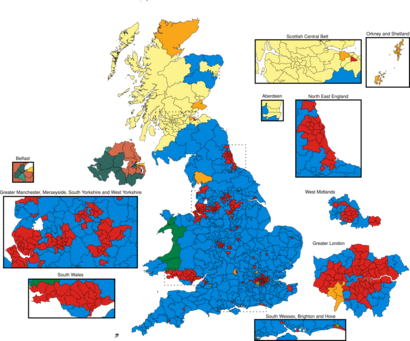

The "Leave" side won with 51.9% of the votes. Most of England and Wales voted to leave, but London, Scotland, and Northern Ireland voted to stay. After the vote, David Cameron resigned. Theresa May became the new Prime Minister. The UK then spent four years negotiating how to leave the EU.

The leaving process was difficult and caused many disagreements in the UK. The UK finally left the EU on 31 January 2020. After leaving, there was an eleven-month transition period. During this time, the UK still followed many EU rules while a new trade deal was worked out. A trade deal was agreed on 30 December 2020.

Contents

Timeline of Brexit

After the public vote on 23 June 2016, where 51.89% voted to leave, Prime Minister David Cameron resigned. On 29 March 2017, the new government, led by Theresa May, officially told the EU that the UK wanted to leave. This started a two-year process.

The UK was supposed to leave on 29 March 2019. But there were many disagreements in the British Parliament. This caused the leaving date to be delayed three times.

The disagreements ended after another general election in December 2019. In this election, Boris Johnson and his Conservative Party won a large number of seats. This allowed Parliament to agree to the leaving deal. The UK officially left the EU at 11:00 PM on 31 January 2020.

After leaving, there was a transition period until 31 December 2020. During this time, the UK still followed EU laws and was part of the EU's customs union and single market. But it was no longer part of the EU's political groups.

In the 1970s and 1980s, some people in the Labour Party wanted to leave the EC. But later, the Conservative Party had more members who wanted to leave. After promising a new vote, Prime Minister David Cameron held the 2016 referendum. He wanted to stay in the EU, but resigned after the "Leave" vote won.

On 29 March 2017, the British government officially started the leaving process by using Article 50 of the EU treaty. This rule explains how a country can leave. Theresa May called an early election in June 2017 to try and get more support for her plans. But her party lost its majority in Parliament.

The UK and EU then started negotiations. The UK wanted to leave the EU's customs union and single market. This led to a deal in November 2018. But the British Parliament voted against this deal three times. Many politicians disagreed about parts of the deal, like the money the UK would pay and the plan for the border with Ireland.

Because the deal was not approved, Brexit was delayed again. Theresa May resigned in July 2019, and Boris Johnson became Prime Minister. He wanted to change parts of the deal and leave by the new deadline. On 17 October 2019, a new deal was agreed.

Parliament approved the new deal for review, but did not pass it into law before the 31 October deadline. This forced the government to ask for another delay. An early general election was held on 12 December 2019. The Conservatives won a large majority, and Boris Johnson said the UK would leave in early 2020. The deal was approved by the UK on 23 January and by the EU on 30 January. It officially started on 31 January 2020.

Ratification and Departure

After the election, the government quickly passed a law to approve the leaving deal. This law became official on 23 January 2020. The European Parliament also approved the deal on 29 January.

At 11:00 PM on 31 January 2020, the UK's membership of the European Union ended. This was 47 years after it first joined. To mark the moment, a countdown clock was shown on 10 Downing Street, and Big Ben chimed.

Transition Period and Final Trade Agreement

After leaving, the UK entered a "Transition Period" for the rest of 2020. During this time, trade, travel, and freedom of movement mostly stayed the same.

The leaving deal included rules for the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. It allowed goods to move freely between them. This meant checks would happen on goods coming into Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK.

During the transition period, the UK and EU continued to negotiate a new trade agreement. On 24 December 2020, they announced that a deal had been reached. This deal was approved by the British Parliament on 30 December. The transition period ended under the terms of this new deal on 31 December 2020.

What "Brexit" Means

The word Brexit is a mix of "British" and "exit." It was first used in 2012 to talk about the UK leaving the EU. By 2016, it was a very common word.

UK and EU Membership History

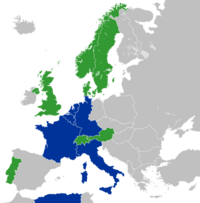

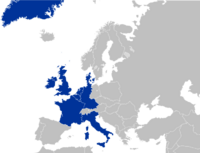

The first European countries to work together signed a treaty in 1951. This created the European Coal and Steel Community. Later, in 1957, the European Economic Community (EEC) was formed. These groups became known as the European Communities (EC) in 1967.

The UK tried to join in 1963 and 1967, but the President of France, Charles de Gaulle, stopped them. He worried the UK would bring too much US influence.

After de Gaulle left office, the UK successfully applied to join the EC. The British Parliament voted to join in 1971. The UK officially became a member on 1 January 1973, along with Denmark and Ireland.

In 1975, the UK held its first national referendum on whether to stay in the EC. Most people, 67.2%, voted to stay.

In 1993, the EC became the European Union (EU) with the Maastricht Treaty. This treaty aimed for closer ties between member countries. The British Parliament approved this treaty without another public vote.

Euroscepticism in the UK

"Euroscepticism" means having doubts or opposition to the European Union. Some British politicians, like Margaret Thatcher, warned against the EU becoming too powerful.

The vote to approve the Maastricht Treaty in 1993 made some people more Eurosceptic. New parties were even formed to push for a referendum on the UK's relationship with the EU.

Role of EU Leadership

How the EU handled big problems also made some people in the UK more Eurosceptic. For example, during the eurozone debt crisis, the EU asked countries to help with bailouts. Critics in the UK felt this was unfair and took away their country's power.

During the 2015 migration crisis, Germany's leader, Angela Merkel, decided to open EU borders to refugees. Many in the UK felt this was forced upon them without asking. This made people more worried about losing control of their own country.

Parties like UKIP used these worries in their campaigns. They said the EU was too powerful and that the UK was losing its independence.

Electoral Success and the 2016 Referendum

UKIP became very successful in elections because of its anti-EU message. In the 2014 European elections, it became the largest UK party. This put pressure on the Conservative Party. It led Prime Minister David Cameron to promise the 2016 referendum on EU membership.

By connecting worries about EU leadership to losing national control, Eurosceptic groups influenced public opinion. This helped lead to the "Leave" vote in the referendum.

Public Opinion Before 2016

From 1977 to 2015, public opinion on the EU changed often. Sometimes more people wanted to stay, and sometimes more wanted to leave. In 1975, two-thirds of British voters wanted to stay in the EC.

Surveys showed that the number of people who wanted to leave the EU or reduce its powers grew from 38% in 1993 to 65% in 2015. However, a survey in late 2015 still showed 60% wanted to stay and 30% wanted to leave.

2016 EU Membership Referendum

Negotiations for Membership Reform

In 2012, Prime Minister David Cameron first said no to a referendum. But then he suggested a future vote to approve changes to Britain's relationship with the EU. On 23 January 2013, Cameron promised a vote on EU membership by the end of 2017 if his party won the 2015 election.

The Conservative Party won the election. Cameron wanted to stay in a reformed EU. He tried to negotiate changes, such as protecting the single market for non-euro countries, reducing rules, and limiting immigration from the EU.

In December 2015, polls showed most people wanted to stay in the EU. But support would drop if Cameron did not get good changes.

The results of the negotiations were announced in February 2016. Some limits on benefits for new EU immigrants were agreed, but they would need EU permission to be used.

On 22 February 2016, Cameron announced the referendum date: 23 June 2016. He said that if the UK voted to leave, the process to exit would start right away. The official question for the vote was: "Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?"

Referendum Result

In the referendum, 51.89% voted to leave the EU, and 48.11% voted to remain. After this result, Cameron resigned. Theresa May became Prime Minister. A petition asking for a second referendum got over four million signatures, but the government rejected it.

| Choice | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| Leave the European Union | 17,410,742 | 51.89 |

| Remain a member of the European Union | 16,141,241 | 48.11 |

| Valid votes | 33,551,983 | 99.92 |

| Invalid or blank votes | 25,359 | 0.08 |

| Total votes | 33,577,342 | 100.00 |

| Registered voters and turnout | 46,500,001 | 72.21 |

| Source: Electoral Commission | ||

| National referendum results (excluding invalid votes) | |

|---|---|

| Leave 17,410,742 (51.9%) |

Remain 16,141,241 (48.1%) |

| ▲ 50% |

|

Leave Remain

| Region | Electorate | Voter turnout, of eligible |

Votes | Proportion of votes | Invalid votes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remain | Leave | Remain | Leave | ||||||

| East Midlands | 3,384,299 | 74.2% | 1,033,036 | 1,475,479 | 41.18% | 58.82% | 1,981 | ||

| East of England | 4,398,796 | 75.7% | 1,448,616 | 1,880,367 | 43.52% | 56.48% | 2,329 | ||

| Greater London | 5,424,768 | 69.7% | 2,263,519 | 1,513,232 | 59.93% | 40.07% | 4,453 | ||

| North East England | 1,934,341 | 69.3% | 562,595 | 778,103 | 41.96% | 58.04% | 689 | ||

| North West England | 5,241,568 | 70.0% | 1,699,020 | 1,966,925 | 46.35% | 53.65% | 2,682 | ||

| Northern Ireland | 1,260,955 | 62.7% | 440,707 | 349,442 | 55.78% | 44.22% | 374 | ||

| Scotland | 3,987,112 | 67.2% | 1,661,191 | 1,018,322 | 62.00% | 38.00% | 1,666 | ||

| South East England | 6,465,404 | 76.8% | 2,391,718 | 2,567,965 | 48.22% | 51.78% | 3,427 | ||

| South West England (inc Gibraltar) | 4,138,134 | 76.7% | 1,503,019 | 1,669,711 | 47.37% | 52.63% | 2,179 | ||

| Wales | 2,270,272 | 71.7% | 772,347 | 854,572 | 47.47% | 52.53% | 1,135 | ||

| West Midlands | 4,116,572 | 72.0% | 1,207,175 | 1,755,687 | 40.74% | 59.26% | 2,507 | ||

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 3,877,780 | 70.7% | 1,158,298 | 1,580,937 | 42.29% | 57.71% | 1,937 | ||

Who Voted Which Way?

Studies showed that people who voted to leave often had lower incomes and fewer qualifications. They also lived in areas with a history of manufacturing jobs and where many Eastern European migrants had moved. Older people were more likely to vote "Leave," while younger people were more likely to vote "Remain."

For example, 64% of people over 65 voted to leave, but only 29% of 18–24-year-olds did. People with less education were more likely to vote leave. Also, households earning less than £20,000 were more likely to vote leave.

There were big differences across the UK. Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain. Most of London also voted to remain. But industrial areas in northern England strongly supported leaving.

People who voted "Leave" believed it would bring a better immigration system, stronger border controls, and more control over UK laws. People who voted "Remain" believed staying in the EU was better for the economy, jobs, and the UK's influence in the world.

Withdrawal Process

Leaving the European Union is guided by Article 50 of the EU treaty. This rule says that any country can leave by telling the European Council. This starts a two-year negotiation period. During this time, the EU and the leaving country try to agree on how they will separate and what their future relationship will be. If no agreement is reached in two years, membership ends. However, all EU countries can agree to extend the time.

Starting Article 50

The 2015 referendum law did not force the government to start Article 50. But the government said it would respect the vote. When Cameron resigned, he said the next Prime Minister would start the process. Theresa May became Prime Minister and said she would wait until 2017 to start Article 50.

In January 2017, the UK's highest court ruled that Parliament had to approve starting Article 50. A law was passed on 16 March 2017 to allow this. On 29 March, Theresa May officially started Article 50. This meant the UK was expected to leave the EU on 29 March 2019.

2017 UK General Election

In April 2017, Theresa May called an early general election for 8 June. She hoped to get more support for her Brexit negotiations. The Conservative Party, Labour, and UKIP all promised to follow the referendum result. Other parties, like the Liberal Democrats, wanted another referendum to try and stay in the EU.

The election resulted in no single party having a clear majority in Parliament. The Conservatives remained the largest party but lost seats. Labour gained many votes and seats.

The Conservatives then made an agreement with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) to help them govern. This agreement included extra money for Northern Ireland and support for Brexit.

UK-EU Negotiations in 2017 and 2018

Before negotiations, May said the UK would not stay in the single market, would end the EU court's power, and would stop free movement of people. The EU wanted to negotiate in two parts: first, agree on money and citizens' rights, then discuss the future relationship. The EU asked the UK to pay a "divorce bill," estimated at £35–39 billion.

Negotiations started on 19 June 2017. They focused on citizens' rights, money, and the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. In December 2017, a partial agreement was reached. It aimed to avoid a hard border in Ireland and protect citizens' rights. After this, EU leaders agreed to move to the second phase: discussing the future relationship and a trade deal.

In March 2018, a 21-month transition period was agreed. In July 2018, the British government published its "Chequers plan" for the future relationship. This plan aimed to keep access to the single market for goods but allow an independent trade policy. This plan caused some government ministers to resign.

May's Agreement and Failed Approval

On 13 November 2018, the UK and EU agreed on a draft leaving deal. May got her government's support, but some ministers resigned because of problems they saw in the deal. It was expected to be hard to get Parliament to approve it. On 25 November, all 27 remaining EU leaders approved the deal.

On 10 December 2018, the Prime Minister delayed the vote in Parliament on her Brexit deal. She faced a likely defeat. This gave her more time to negotiate. Also on this day, the European Court of Justice ruled that the UK could stop its leaving process if it wanted to.

Some Conservative MPs strongly opposed May's deal. They did not like the "Irish backstop" plan, the financial payment, or that the UK would still follow some EU rules.

On 15 January 2019, the House of Commons voted against the deal by a large margin (432 to 202). This was the biggest defeat for a UK government ever. A vote of no confidence in the government was then held, but it was rejected.

May tried again on 12 March, but the deal was defeated again by 391 votes to 242. The Speaker of the House of Commons then said that a third vote could only happen if the deal was very different.

The deal was brought back on 29 March without some attached understandings. It was defeated again by 344 votes to 286.

Article 50 Extensions and Johnson's Agreement

On 20 March 2019, the Prime Minister asked the EU to delay Brexit until 30 June 2019. The EU rejected this date and offered two other options: 12 April 2019 (if no deal was approved) or 22 May 2019 (if May's deal was approved). Parliament approved these new dates.

Because Parliament did not approve the deal by 29 March, the UK was set to leave on 12 April 2019. On 10 April 2019, after more talks, the EU agreed to another delay, until 31 October 2019. If the deal was passed before October, Brexit would happen on the first day of the next month.

The EU had said it would not change the leaving deal. But after Boris Johnson became Prime Minister on 24 July 2019, the EU changed its mind. On 17 October 2019, a new, revised leaving deal was agreed. This deal included new arrangements for Northern Ireland.

The British Parliament passed a law that forced the Prime Minister to ask for a third delay if no deal was reached by October 2019. On 28 October 2019, the EU agreed to this third delay, setting a new leaving deadline of 31 January 2020.

2019 UK General Election

After Boris Johnson could not get Parliament to approve the revised deal, he called for an early election. This election was held on Thursday 12 December 2019. Polls showed the Conservatives were leading.

In the election, the Conservative Party promised to leave the EU with the deal agreed in October 2019. Labour wanted to renegotiate the deal and hold another referendum. The Liberal Democrats wanted to stop Brexit completely. The Scottish National Party wanted another independence referendum. The Brexit Party wanted to leave the EU without a deal.

Boris Johnson's Conservatives won a large majority of 80 seats. Labour had its worst election result since 1935. This result ended the disagreements in Parliament and made sure the UK would leave the EU on 31 January 2020.

Ratification and Departure

After the election, the government quickly passed a law to approve the leaving deal. This law became official on 23 January 2020. The European Parliament also approved the deal on 29 January.

At 11:00 PM on 31 January 2020, the UK's membership of the European Union ended. This was 47 years after it first joined. To mark the moment, a countdown clock was shown on 10 Downing Street, and Big Ben chimed.

Transition Period and Final Trade Agreement

After leaving, the UK entered a "Transition Period" for the rest of 2020. During this time, trade, travel, and freedom of movement mostly stayed the same.

The leaving deal included rules for the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. It allowed goods to move freely between them. This meant checks would happen on goods coming into Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK.

During the transition period, the UK and EU continued to negotiate a new trade agreement. On 24 December 2020, they announced that a deal had been reached. This deal was approved by the British Parliament on 30 December. The transition period ended under the terms of this new deal on 31 December 2020.

UK Laws After Brexit

European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018

In October 2016, Theresa May promised a "Great Repeal Bill." This bill would cancel the 1972 law that made EU law apply in the UK. It would also copy all existing EU laws into British law. This bill was later called the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill.

The bill passed its first vote in Parliament on 12 September 2017. It was changed several times. When it became law on 26 June 2018, it was called the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018.

This law set a deadline for the government to decide what to do if no deal was reached. It also said that any final leaving deal would need another law passed by Parliament. The Act did not change the two-year time limit for negotiations under Article 50.

The Withdrawal Act allowed for different outcomes, even leaving without a deal. It gave the government power to set the exact "exit day" and cancel the 1972 law. The exit day had to be the same day and time that EU treaties stopped applying to the UK.

Exit Day

The official "exit day" was 11:00 PM on 31 January 2020. The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 defined this date.

Additional Government Bills

A report in March 2017 said that many new laws would be needed after Brexit. These laws would cover areas like customs, immigration, and farming. It was thought that up to 15 new Brexit laws might be needed.

The House of Lords also published reports on different Brexit topics, such as:

- Trade options

- UK-Irish relations

- Security cooperation

- Fisheries

- Environment and climate change

- Justice for families and businesses

- Trade in services

European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020

The European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 made the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement legal in the UK. This bill was first introduced in October 2019. It was reintroduced after the 2019 general election. It passed its final vote on 9 January 2020. This law became official on 23 January 2020, just nine days before the UK left the EU.

Planning for No-Deal Brexit

On 19 December 2018, the EU Commission shared its plan for a "no-deal" Brexit. This plan covered specific areas if the UK left without an agreement.

The UK government also made plans. The Department for International Trade was created to make new trade agreements with countries outside the EU. In March 2019, the government said it would cut many import taxes to zero if there was a no-deal Brexit. However, some groups, like the Confederation of British Industry, said this would harm the economy.

In June 2020, Germany's leader, Angela Merkel, said the EU must prepare for trade talks with the UK to fail. She said negotiations were speeding up to try and get a deal by the end of the year.

Impact of Brexit

The effects of Brexit depended on whether the UK left with a deal or without one. In 2017, it was noted that the UK would no longer be part of about 759 international agreements with 168 non-EU countries after leaving the EU.

Economic Effects

Many experts believed Brexit would harm the economies of the UK and some EU countries. There was a general agreement that Brexit would likely reduce the UK's income per person in the long run. Studies found that the uncertainty caused by Brexit reduced British economic growth, business investment, jobs, and international trade from June 2016 onwards.

A 2019 study found that British companies moved more of their business to the EU after the Brexit vote. Meanwhile, European companies invested less in the UK. The British government's own analysis in 2018 showed that UK economic growth could be 2–8% lower over 15 years after Brexit.

In January 2024, the Mayor of London's Office reported that Brexit had caused nearly 300,000 fewer jobs in London and two million fewer jobs nationwide. It also said that the average person was nearly £2,000 worse off in 2023 because of Brexit.

Local and Geographic Effects

The border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland was a big concern. Since 2005, this border had been almost invisible. After Brexit, it became the only land border between the UK and the EU. Everyone agreed that a "hard border" (with checks and controls) should be avoided. This was important to protect the Good Friday Agreement, which ended the conflict in Northern Ireland.

To avoid a hard border, the EU suggested a "backstop agreement." This would keep the UK in the Customs Union and Northern Ireland in parts of the Single Market. The UK Parliament rejected this. Later, a different plan, the "Northern Ireland Protocol," was agreed. Under this plan, Northern Ireland is outside the EU single market, but EU rules for goods still apply. This means no customs checks between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Instead, there are some checks on goods coming from Great Britain to Northern Ireland.

After the Brexit referendum, the Scottish Government wanted another independence referendum. This was because Scotland voted to stay in the EU, while England and Wales voted to leave. In 2014, 55% of Scottish voters chose to stay in the UK. But in the 2016 Brexit vote, 62% of Scottish voters wanted to stay in the EU. In March 2017, the Scottish Parliament voted for another independence referendum.

Gibraltar, a British territory next to Spain, was also affected. Spain claims Gibraltar. In late 2018, the UK and Spanish governments agreed that disputes over Gibraltar would not stop Brexit talks. In December 2020, Spain and the UK agreed on future arrangements for Gibraltar.

The French and British governments agreed to keep the "Le Touquet Agreement." This allows UK border checks to happen in France, and French checks to happen in the UK.

Effects on the European Union

Brexit meant the EU lost its second-largest economy and third-most populated country. The UK was also the second-largest net contributor to the EU budget.

The UK is no longer a shareholder in the European Investment Bank. The remaining EU countries increased their contributions to keep the bank's funding the same.

Before Brexit, the European Medicines Agency and European Banking Authority moved their main offices from London to Amsterdam and Paris.

Effects on Different Areas

The UK left the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which gave money to farmers in the EU. This allowed the UK to create its own farming policy. The UK also left the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), which allowed all EU countries to fish in British waters. By leaving the CFP, the UK could set its own fishing rules.

Brexit also created challenges for British universities and research. The UK lost some research funding from the EU. It also became harder to hire researchers from the EU, and British students faced more difficulties studying in the EU.

A study in early 2019 found that Brexit could reduce the number of staff in the National Health Service (NHS). It also raised worries about access to vaccines and medicines. The number of non-British EU nurses registering with the NHS dropped after the referendum. However, the total number of EU staff in the NHS has increased since 2016.

After Brexit, EU laws no longer have power over British laws. The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 copied EU laws into British law. The British Parliament can now decide which of these laws to keep, change, or remove. British courts are also no longer bound by decisions from the EU Court of Justice.

After Brexit, the UK can control immigration from EU countries. The UK government planned a new "skills-based immigration system." EU citizens already living in the UK could apply to stay through the EU Settlement Scheme. Studies suggest that ending free movement will likely lead to fewer people moving from EU countries to the UK.

The UK also left the European Common Aviation Area. This means new agreements were needed for flights between the UK and EU. The UK now has its own air service agreements with many countries. Ferry services continue, but with new customs checks.

Some lawmakers worried that Brexit could create security problems for the UK. This is because UK police and counter-terrorism forces would no longer have access to some EU security databases.

Some experts believe the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK hid the effects of Brexit in 2021. In December 2021, economists said Brexit's economic impact on the UK was "negative but uncertain." The Office for Budget Responsibility suggested that the new trade deal could reduce British productivity by 4% over time.

Brexit was also seen as a reason for the 2021 UK fuel supply crisis. It made the shortage of truck drivers worse. In July 2021, it was estimated that the UK needed up to 100,000 more truck drivers.

While trade between the UK and EU dropped in 2020 due to lockdowns, by 2022, trade in both directions had risen to higher levels than before Brexit. Goods trade had fallen, but this was balanced by an increase in professional services.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Salida del Reino Unido de la Unión Europea para niños

In Spanish: Salida del Reino Unido de la Unión Europea para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |