UK Independence Party facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

UK Independence Party

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Abbreviation | UKIP |

| General Secretary | Donald Mackay |

| Spokesperson | Calvin Robinson |

| Leader | Nick Tenconi |

| Honorary President | Neil Hamilton |

| Chairman | Ben Walker |

| Treasurer | Ian Garbutt |

| Founder | Alan Sked |

| Founded | 3 September 1993 |

| Preceded by | Anti-Federalist League |

| Headquarters | Henleaze Business Centre, 13 Harbury Road, Henleaze, Bristol, BS9 4PN |

| Youth wing | Young Independence |

| Membership (2020) | |

| Ideology |

|

| Political position | Right-wing to far-right |

| National affiliation | Patriots Alliance - English Democrats and UKIP |

| European affiliation |

|

| European Parliament group |

|

| Colours | Purple Gold |

| Slogan | People not politics |

The UK Independence Party (UKIP) is a political party in the United Kingdom. It is known for its strong belief that the UK should not be part of the European Union (EU). This idea is called Euroscepticism. The party also has right-wing views and often uses populist ideas, meaning it tries to appeal directly to ordinary people.

UKIP had its biggest success in the mid-2010s. At that time, it had two members in the UK Parliament. It was also the largest party representing the UK in the European Parliament. The party is currently led by Nick Tenconi.

UKIP started as the Anti-Federalist League in 1991. It was founded by Alan Sked in London. The party changed its name to UKIP in 1993. Its main goal was to get the UK out of the EU. For a while, another party, the Referendum Party, was more popular. But after 1997, many of its members joined UKIP.

Nigel Farage became a very important figure in UKIP. He became leader in 2006. Under his leadership, UKIP started to focus on more issues, like concerns about immigration. This helped the party gain a lot of support in elections between 2013 and 2015. After the UK voted to leave the EU in 2016, Farage stepped down. Since then, UKIP's support and membership have decreased a lot. The party has also faced many internal changes.

UKIP is seen as a right-wing populist party. Its main focus has always been on leaving the EU. It also supports British nationalism, which means promoting a strong British identity. The party wants to lower immigration and has traditional views on social issues. It also supports liberal economic policies, which means it believes in less government involvement in the economy.

Contents

Understanding UKIP's Journey

How UKIP Started: 1991–2004

UKIP began as the Anti-Federalist League in 1991. It was created by a historian named Alan Sked. This group was against the Maastricht Treaty, which was a big agreement for European countries. They wanted the UK to leave the European Union. Sked himself ran for Parliament in 1992 but got very few votes.

On September 3, 1993, the group changed its name to the UK Independence Party. They chose "UK" instead of "British" to avoid confusion with other groups. In the 1994 European Parliament election, UKIP got 1% of the votes. Many people saw them as a party focused on just one issue: leaving the EU.

After 1994, UKIP lost some support to the Referendum Party, which had more money. In the 1997 general election, UKIP got only 0.3% of the national vote. However, after the Referendum Party closed down, many of its members joined UKIP.

After the 1997 election, Alan Sked left UKIP. Michael Holmes became the leader. In the 1999 European Parliament elections, UKIP did better, getting 6.5% of the vote and winning three seats. This was the first time they had elected members in the European Parliament.

Later, Jeffrey Titford and then Roger Knapman became leaders. Knapman had experience in mainstream politics. In the 2001 general election, UKIP got 1.5% of the vote. In 2004, UKIP changed its structure to be a private company.

Growing Stronger: 2004–2014

UKIP's support grew a lot in the 2004 European Parliament elections. They came in third place, getting 2.6 million votes and 12 seats. This was helped by more funding and support from a TV personality, Robert Kilroy-Silk. However, Kilroy-Silk later left UKIP to start his own party.

In the 2005 general election, UKIP got 2.2% of the vote but no seats. In 2006, Nigel Farage was elected leader. He tried to make UKIP appeal to more people by adding new policies. These included reducing immigration, cutting taxes, and bringing back grammar schools. Farage presented himself as an "ordinary person" who was against the main political parties.

After a scandal about politicians' expenses, UKIP gained more support. In the 2009 European Parliament election, they got 2.5 million votes and 13 members. They became the second-largest party in the European Parliament from the UK.

Farage resigned as leader in 2009, and Lord Pearson took over. Lord Pearson focused on opposing immigration. In the 2010 general election, UKIP got 3.1% of the vote but no seats. Farage was re-elected leader in 2010.

Farage then focused on building local support. UKIP did very well in the 2013 local elections, winning 147 new councillors. This was the best result for a smaller party in Britain since World War II.

Becoming a Major Force: 2014–2016

In 2014, UKIP was recognized as a "major party." In the 2014 local elections, they won 163 seats. In the 2014 European Parliament elections, UKIP received the most votes of any British party (27.5%). They won 24 seats, which was a huge success. This made Farage and UKIP very well-known. It was the first time since 1906 that a party other than Labour or the Conservatives won the most votes in a UK-wide election.

UKIP gained its first Member of Parliament (MP) when Douglas Carswell left the Conservative Party and won a special election in October 2014. Another Conservative MP, Mark Reckless, also joined UKIP and won a special election in November.

In the 2015 general election, UKIP got over 3.8 million votes (12.6%). This made them the third most popular party. However, they only won one seat, held by Douglas Carswell. Farage had said he would resign if he didn't win his own seat, and he did, but the party later asked him to return as leader.

In the 2016 Welsh Assembly election, UKIP significantly increased its votes and won seven seats. UKIP also took control of its first local council, Thanet, in May 2015.

The Brexit Vote and After: 2016–Present

To stop losing votes to UKIP, the Conservative government promised a vote on whether the UK should stay in the EU. This was the 2016 Brexit referendum. UKIP strongly supported leaving the EU. Farage was often in the news during the campaign, talking about the impact of immigration. In June 2016, the UK voted to leave the EU. This was UKIP's main goal achieved.

Party Changes (2016–2018)

After the Brexit vote, Farage resigned as UKIP leader. Diane James was elected but resigned after only 18 days. Paul Nuttall then became leader. In 2017, UKIP's only MP, Douglas Carswell, left the party. In the 2017 local elections, UKIP lost almost all the seats they were defending. Many former members suggested the party should close down. In the 2017 general election, UKIP got very few votes and no seats. Nuttall resigned, and Steve Crowther became interim leader.

Henry Bolton was elected leader in 2017. However, he faced a vote of no confidence from the party in January 2018. Many members left the party in protest. Gerard Batten became interim leader and then permanent leader in April 2018.

New Directions (2018–2019)

In the 2018 local elections, UKIP lost almost all its seats. Under Gerard Batten, the party focused more on opposing certain religions and worked with some controversial figures. This led to many high-profile members, including Nigel Farage, leaving the party. Farage said UKIP was not founded to fight a "religious crusade."

By April 2019, most of the UKIP members elected to the European Parliament in 2014 had left the party. Many joined Nigel Farage's new Brexit Party. In the 2019 local elections, UKIP lost about 80% of its seats. In the European elections later that month, UKIP got only 3.3% of the vote and lost all its remaining seats.

Gerard Batten resigned as leader in June 2019. Richard Braine was elected leader in August 2019. He faced criticism for some of his comments.

Challenges and Decline (2019–Present)

In October 2019, UKIP faced more leadership problems. Richard Braine was suspended from the party and then resigned. Patricia Mountain became interim leader for the December 2019 general election. UKIP only had 44 candidates in this election. The party received only 22,817 votes nationwide (0.1% of the total), which was its lowest result ever. They did not win any seats.

In January 2020, David Kurten, UKIP's last member in the London Assembly, left the party. This ended UKIP's presence there. In March 2020, the party was reported to be in financial difficulty.

Freddy Vachha was elected leader in June 2020 but was suspended in September. Neil Hamilton became interim leader and then permanent leader in October 2021.

In the 2021 Welsh Senedd election, UKIP performed very poorly. Neil Hamilton lost his seat, meaning UKIP no longer had any elected members outside of local councils in England. In the 2021 local elections, UKIP lost all the seats it was defending.

In April 2023, the party changed its rules about who could join. In the May 2023 local elections, UKIP lost all its remaining council seats. This meant the party had no elected representatives at any level of government, except for some parish and town councils.

In early 2024, Neil Hamilton announced he would retire as leader. Lois Perry was elected leader in May 2024 but resigned in June due to health issues. Deputy leader Nick Tenconi took over as interim leader. In the 2024 general election, UKIP's vote share declined even further, and they won no seats. On August 2, 2024, Calvin Robinson became the party's lead spokesman. Nick Tenconi became the permanent leader on February 5, 2025.

UKIP's Beliefs and Goals

Right-Wing Populism Explained

UKIP is considered a right-wing party. Experts describe it as a "right-wing populist" party. Populism means a political group that claims to represent "ordinary people" against a group of "elites" or "dangerous others." UKIP's founders described it as a populist party from the start.

The party often says there's a big difference between the British people and the politicians who govern them. UKIP claims to speak for ordinary people against this political elite. For example, Nigel Farage called UKIP supporters the "People's Army." He often met journalists in pubs to show he was a "man of the people."

UKIP uses simple language, calling its policies "common sense." They try to seem like a clear choice compared to the main parties. They often say the three main parties (Conservatives, Labour, and Liberal Democrats) are all the same.

National Identity and British Unity

A core part of UKIP's beliefs is about national identity. The party is nationalist, meaning it believes the UK should be fully governed by its own national state. UKIP says it supports "civic nationalism," which means it welcomes people of all backgrounds who identify as British. They say they are not racist.

However, UKIP also talks about "restoring Britishness" and stopping what they see as the "Islamification" of Britain. They also oppose strong Welsh, Scottish, and Irish nationalisms. Some people say this view makes it harder for UKIP to claim its nationalism is truly inclusive.

UKIP sees itself as a party that supports the unity of Britain. However, most of its support comes from England. Farage once called UKIP's growth "a very English rebellion." Some experts say UKIP mixes up English identity with British identity. They believe UKIP's ideas often look back to a past image of England.

UKIP also wants to fix what it sees as an unfair situation for England within the UK. They have supported the idea of an English Parliament, similar to the ones in Wales and Scotland. They also wanted to make St. George's Day and St. David's Day public holidays in England and Wales.

Views on Europe, Immigration, and Global Affairs

UKIP strongly believes the UK should not be part of the European Union. This has always been their main issue. They say the EU is undemocratic and takes away the UK's independence. They also blame the EU for high immigration to the UK, especially from Eastern Europe. UKIP believes the EU is corrupt and inefficient.

UKIP wanted the UK to leave the EU, stop payments to the EU, and end EU treaties. They wanted to keep trading with European countries. They eventually pushed for a public vote (referendum) on leaving the EU. UKIP also emphasizes the UK's connections with countries in the Commonwealth of Nations. They say they are not against European people, but against the EU system.

Immigration has been a very important issue for UKIP. They believe that being in the EU caused too much immigration to the UK. UKIP has used campaign materials that suggest EU migrants cause problems with crime, housing, and public services. Farage also talked about how immigration changes culture.

UKIP proposed a ban on unskilled migrants coming to the UK for five years. They also wanted a points-based system for skilled migrants, like Australia has. They aimed to reduce net annual immigration to between 20,000 and 50,000 people. UKIP also wanted immigrants to have health insurance and wait five years before claiming state benefits.

UKIP gained support because many Britons were concerned about immigration after 2008. However, the party's campaign against immigration has been criticized. Some people said it used ideas that were unfair to immigrants.

UKIP also wanted to cut the foreign aid budget. They supported increasing the UK's defense budget. They were against the UK getting involved in military conflicts that were not directly in the UK's interest. For example, they opposed military action in the Syrian civil war in 2014. The party was also known for having a friendly view towards Russia.

Economic Ideas

UKIP generally supports a capitalist market economy. They believe in a global free market, where businesses can trade freely. Some experts say UKIP wants to keep the good parts of the market economy but get rid of the negative parts. For example, they want free movement of money but less free movement of workers.

UKIP's early supporters often believed in liberal economic ideas. They were influenced by Margaret Thatcher, a former Prime Minister. Farage said UKIP was the "true inheritors" of Thatcher's ideas. Some suggest a UKIP government would follow very strong Thatcher-like economic policies.

UKIP has been described as a libertarian party, meaning it supports individual freedom and limited government. However, some critics say this isn't true because of their traditional social views and some policies that protect local industries.

UKIP would allow businesses to prefer British workers over migrants. They also wanted to change some laws about discrimination. Farage said his comments on these issues were misunderstood.

Social Policies

UKIP's approach to many social issues is seen as traditional and conservative. They were against allowing same-sex marriage in the United Kingdom. UKIP wanted to get rid of the Human Rights Act 1998 and leave the European Convention on Human Rights. They also wanted a public vote on bringing back the death penalty.

In 2015, Farage suggested that non-British citizens with certain health conditions should not get free treatment on the National Health Service (NHS). He said the NHS should be for British people who have paid into the system. Critics have claimed that UKIP secretly wanted to privatize the NHS.

Farage also spoke about concerns regarding certain religious groups in the UK. He called for Western countries to promote their traditional heritage and criticized government policies that he felt led to social separation. In its 2017 plan, UKIP wanted to ban certain religious courts and face coverings in public. They said this would help people integrate into British society.

UKIP is different from other major UK parties because it does not support renewable energy or lower carbon emissions. They often question the idea of climate change. Farage and other UKIP figures have spoken against wind farms. They support using fossil fuels, nuclear power, and fracking. UKIP also wanted to protect green spaces.

In its 2015 election plan, UKIP promised to teach British history in schools. They also wanted to stop sex education for children under 11. UKIP suggested that students could take apprenticeship qualifications instead of some exams. They also wanted to change the goal of having 50% of school leavers go to university.

Farage believed that British Overseas Territories like Gibraltar should have representatives in the UK Parliament. He felt that all citizens affected by British laws should have a voice in Parliament.

Who Supports UKIP?

Money Behind the Party

In its early years, UKIP relied on a few big financial supporters. A report from 2012 suggested that money for the party would come from the "hedge fund industry."

In 2013, UKIP's total income was over £2.4 million. Most of this came from donations and membership fees. Large donations over £7,500 must be reported by law.

Several wealthy people have supported UKIP. In 2009, Stuart Wheeler, a big donor to the Conservative Party, gave £100,000 to UKIP. In 2014, Arron Banks increased his donation to UKIP to £1 million. The millionaire Paul Sykes also gave over £1 million for UKIP's 2014 European Parliament campaign.

In December 2014, Richard Desmond, who owns several newspapers, donated £300,000 to UKIP. His newspapers then supported UKIP in the 2015 general election. He gave another £1 million just before the election.

Party Members

UKIP's membership grew from 2002 to 2004. It stayed around 16,000 members in the late 2000s. By July 2013, it had grown to 30,000 members, and by May 2015, it reached 45,000. However, membership then fell to 32,757 in November 2016 and as low as 18,000 by January 2018.

In June 2018, some well-known social media activists joined the party, which led to about 500 new members. In July 2018, the party gained 3,200 new members, a 15% increase. By December 2020, UKIP reported having 3,888 members.

Who Votes for UKIP?

In its early days, UKIP aimed for middle-class voters in southern England who were against the EU. Many thought UKIP supporters were mainly former Conservative voters.

After 2009, UKIP started to appeal more to white, working-class people. These were often people who used to vote for the Labour Party or had stopped voting. This meant UKIP's support didn't fit the usual left-right political lines.

Studies in 2014 found that UKIP's supporters were often older, male, working-class, white, and had less education. For example, 57% of UKIP supporters were over 54, and only 1 in 10 were under 35. This is because UKIP's ideas appealed more to older generations.

Most UKIP supporters (99.6%) identified as white. Over half (55%) had left school by age 16. This suggests the party appealed most to voters with less formal education. UKIP's voters were also more working-class than any other party's supporters. They were often described as the "left behind" group in society.

However, some studies also found that UKIP got votes from lower professionals and managers. They also noted that UKIP drew more votes from Conservative voters than Labour voters.

Studies showed that being against the EU was the main reason people voted for UKIP. Concerns about immigration and distrust of mainstream politicians were also important.

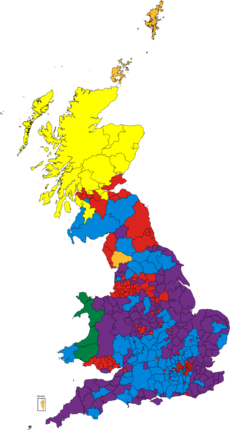

UKIP has been most successful in eastern and southern England, and in some working-class areas in Northern England and Wales. They have not done well in London or in university towns with younger, more diverse populations.

Younger Britons, university graduates, and ethnic minorities generally do not support UKIP. In 2014, a poll showed that only 3% of young people aged 17-22 planned to vote for UKIP.

UKIP supporters are sometimes called "Kippers." After many members left the party in 2017, one expert said that "Former Kippers... literally sprinted over to the Conservatives."

How UKIP is Organized

Leadership Structure

| Leader of the UK Independence Party | |

|---|---|

|

Incumbent

Nick Tenconi (Interim) since 16 June 2024 |

|

| Term length | Four years |

| Inaugural holder | Alan Sked |

| Formation | 3 September 1993 |

The leader of UKIP is chosen by a vote of all paid-up party members. The person with the most votes wins. If there's only one candidate, they become leader without a vote. The leader usually serves for four years. If the leader's position becomes empty suddenly, the party's National Executive Committee (NEC) chooses an interim leader. The leader can also choose a Deputy Leader.

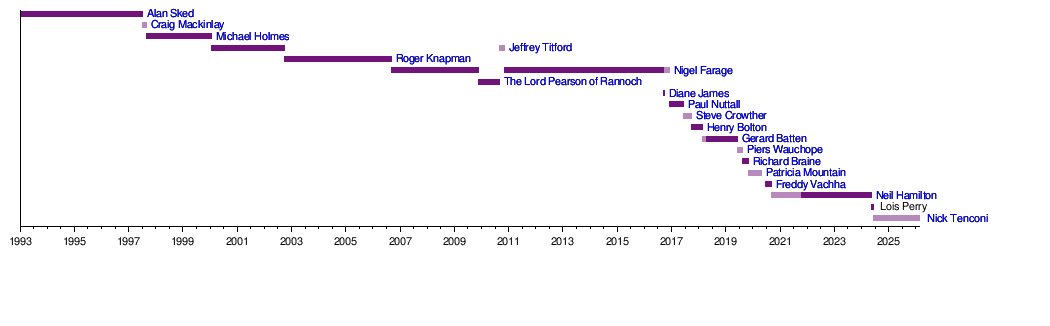

| Leader | Took office | Left office | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alan Sked | 3 September 1993 | July 1997 | Party founder; left party in 1997 |

| Craig Mackinlay was acting leader during this interim | ||||

| 2 | Michael Holmes | September 1997 | 22 January 2000 | MEP 1999–2002; left party in 2000 |

| 3 | Jeffrey Titford | 22 January 2000 | 5 October 2002 | MEP 1999–2009; left party in 2023 |

| 4 | Roger Knapman | 5 October 2002 | 12 September 2006 | MEP 2004–2009 |

| 5 | Nigel Farage | 12 September 2006 | 27 November 2009 | Former chairman; MEP 1999–2020; left party in 2018 |

| 6 | The Lord Pearson of Rannoch | 27 November 2009 | 2 September 2010 | Member of House of Lords; left party in 2019 |

| Jeffrey Titford was acting leader during this interim | ||||

| (5) | Nigel Farage | 5 November 2010 | 16 September 2016 | |

| 7 | Diane James | 16 September 2016 | 4 October 2016 | Leader-elect, MEP 2014–2019; left party in 2016 |

| Nigel Farage was acting leader during this interim | ||||

| 8 | Paul Nuttall | 28 November 2016 | 9 June 2017 | Deputy leader 2010–2016; MEP 2009–2019; left party in 2018 |

| Steve Crowther was acting leader during this interim | ||||

| 9 | Henry Bolton | 29 September 2017 | 17 February 2018 | Left party in 2018 |

| Gerard Batten was acting leader during this interim | ||||

| 10 | Gerard Batten | 14 April 2018 | 2 June 2019 | MEP 2004–2019 |

| Piers Wauchope was acting leader during this interim | ||||

| 11 | Richard Braine | 10 August 2019 | 30 October 2019 | Suspended from party in October 2019; subsequently resigned as leader |

| Patricia Mountain was acting leader during this interim until 25 April 2020 | ||||

| Leadership was vacant until 22 June 2020 | ||||

| 12 | Freddy Vachha | 22 June 2020 | 12 September 2020 | Chairman of UKIP London, Leadership candidate in 2019. Suspended from party on 12 September 2020 |

| 13 | Neil Hamilton | 12 September 2020 | 13 May 2024 | Initially served as interim leader; substantiated on 19 October 2021 |

| 14 | Lois Perry | 13 May 2024 | 15 June 2024 | |

| Nick Tenconi was interim leader during this period | ||||

| 15 | Nick Tenconi | 5 February 2025 | Present | |

Leadership Timeline

Deputy Leaders

| Deputy Leader | Tenure | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Craig Mackinlay | 1997–2000 | Left party in 2005 |

| 2 | Graham Booth | 2000–02 | MEP 2002–2008; died 2011 |

| 3 | Mike Nattrass | 2002–06 | MEP 2004–2014; left party in 2013 |

| 4 | David Campbell Bannerman | 2006–10 | MEP since 2009; left party in 2011 |

| 5 | The Viscount Monckton of Brenchley | Jun–Nov 2010 | Leader of UKIP in Scotland, 2013 |

| 6 | Paul Nuttall | 2010–16 | MEP since 2009; left party in 2018 |

| 7 | Peter Whittle | 2016–17 | London AM since 2016; left party in 2018 |

| 8 | Margot Parker | 2017–18 | MEP 2014–2019; left party in 2019 |

| 9 | Mike Hookem | 2018–19 | MEP 2014–2019 |

| 10 | Pat Mountain | 2020 | Interim Leader 2019, NEC Member |

| 11 | Rebecca Jane | 2022–2024 | |

| 12 | Nick Tenconi | May - June 2024 | |

Party Chairmen

| Chairman | Tenure | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nigel Farage | 1998–2000 | Later became Party Leader |

| 2 | Mike Nattrass | 2000–02 | |

| 3 | David Lott | 2002–04 | |

| 4 | Petrina Holdsworth | 2004–05 | |

| 5 | David Campbell Bannerman | 2005–06 | |

| 6 | John Whittaker | 2006–08 | |

| 7 | Paul Nuttall | 2008–2010 | Later became Party Leader |

| 8 | Steve Crowther | 2010–2016 | |

| 9 | Paul Oakden | 2016–18 | |

| 10 | Tony McIntyre | 2018 | |

| 11 | Kirstan Herriot | 2018–2019 | |

| 12 | Ben Walker | 2020– | |

Regional Organization

UKIP is divided into 12 regions across the UK. There is also a branch in Gibraltar.

In 2013, UKIP Scotland faced problems and was dissolved. However, after David Coburn won a European Parliament seat in Scotland in 2014, he became the leader of UKIP Scotland.

In August 2018, Gareth Bennett was elected leader of UKIP in Wales.

UKIP's Elected Members

In the House of Commons

The UK's voting system makes it hard for smaller parties like UKIP to win seats in the House of Commons. This is because votes are spread out, not concentrated in specific areas. UKIP believed the best way to win a seat was through special elections called by-elections.

In 2008, Bob Spink, an MP, joined UKIP but later left. In 2014, two Conservative MPs, Douglas Carswell and Mark Reckless, switched to UKIP. They then won their seats in by-elections. Carswell became the first MP elected to represent UKIP.

In the 2015 general election, Carswell kept his seat, but Reckless lost his. UKIP got 12.6% of the total votes, making them the third-largest party by vote share. However, they only won one seat. This led to calls for changes to the voting system. Carswell left UKIP in March 2017, leaving the party with no MPs. In the 2017 election, UKIP got only 1.8% of the votes and no seats.

In the House of Lords

UKIP gained its first member in the House of Lords in 1995, Lord Grantley. However, he left in 1999. Another peer, The Earl of Bradford, also joined and left in 1999.

In 2007, Lord Pearson of Rannoch and Lord Willoughby de Broke joined UKIP. Lord Pearson later became party leader. By December 2018, most of UKIP's peers had left the party. Lord Pearson resigned his membership in October 2019, leaving UKIP with no members in the House of Lords.

In Devolved Parliaments and Assemblies

UKIP has also run in elections in Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales.

Northern Ireland

In October 2012, UKIP gained its first member in the Northern Ireland Assembly, David McNarry. However, the party did not win any seats in the 2016 or 2017 elections.

Scotland

UKIP has had very little support in Scotland and has no representatives in the Scottish Parliament. They ran candidates in the 2011, 2016, and 2021 Scottish Parliament elections but did not win any seats.

Wales

UKIP ran candidates for the Senedd (Welsh Parliament). In the 2016 election, they entered the Senedd for the first time, winning seven seats. However, many of their members later left the party. After the 2021 Senedd election, UKIP was left with no members in the Senedd.

In Local Government

UKIP initially did not focus much on local elections. But Nigel Farage realized that building local support could help the party. They started to focus on local elections in 2011.

UKIP won its first local council election in 2000. Over the years, many local councillors from other parties joined UKIP. In May 2013, UKIP gained 139 seats in local elections, bringing their total to 147. They became the main opposition party in six English county councils.

In the 2013 and 2014 local elections, UKIP made big gains. In the 2015 local elections, UKIP took control of Thanet District Council, their first council majority. However, they lost control later that year. They briefly regained control in 2016.

In the 2017 local elections, UKIP lost almost all the seats they were defending. In the 2018 local elections, they lost 123 seats. In the 2019 local elections, UKIP suffered severe losses, with their number of councillors falling to 31.

In the 2021 local elections, UKIP lost all 48 council seats they were defending in England. They also won no seats in the London Assembly or for mayors. In the 2022 local elections, they lost all three seats they were defending.

In the 2023 local elections, UKIP lost all its remaining council seats. This means the party no longer has any elected representatives at the council level. They only have a few members on parish and town councils, which are the lowest level of local government.

In the European Parliament

Because UKIP was against the European Union, they did not recognize the European Parliament's authority. However, after 1997, they decided their elected members would take their seats to promote their anti-EU message.

In the 1999 European Parliament election, three UKIP members were elected. They joined a group called Europe of Democracies and Diversities (EDD). After the 2004 election, 12 UKIP members were elected. They formed a new group called Independence and Democracy. After the 2009 election, UKIP helped form a new right-wing group called Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD).

After the 2014 European Parliament election, UKIP won 24 seats, the most of any British party. They formed a new group called Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD).

UKIP members in the European Parliament were often criticized for not attending many votes. Farage said their goal was not to vote for more EU laws, but to show that power should be with the UK Parliament.

Former Members of the European Parliament

UKIP had no members in the European Parliament after the 2019 EU election. Twenty-four UKIP members were elected in 2014, but many later left the party. For example, James Carver, William Dartmouth, Bill Etheridge, Patrick O'Flynn, Louise Bours, Nigel Farage, David Coburn, Paul Nuttall, Peter Whittle, Julia Reid, Jonathan Bullock, Jill Seymour, Jane Collins, Margot Parker, Jonathan Arnott, and Ray Finch all left UKIP. Many of them joined the Brexit Party.

Election Results Summary

European Parliament Elections

| Election year | Leader | # of total votes | % of overall vote | # of seats won | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Alan Sked | 150,251 #8th |

1.0% |

0 / 87

|

No seats |

| 1999 | Jeffrey Titford | 696,057 #4th |

6.5% |

3 / 87

|

Opposition |

| 2004 | Roger Knapman | 2,650,768 #3rd |

15.6% |

12 / 87

|

Opposition |

| 2009 | Nigel Farage | 2,498,226 #2nd |

16% |

13 / 87

|

Opposition |

| 2014 | Nigel Farage | 4,352,251 #1st |

27.5% |

24 / 87

|

Opposition |

| 2019 | Gerard Batten | 554,463 #8th |

3.2% |

0 / 87

|

No seats |

General Elections

| Election year | Leader | # of total votes | % of overall vote | # of seats won | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Alan Sked | 105,722 |

0.3% |

0 / 659

|

No seats |

| 2001 | Jeffrey Titford | 390,563 |

1.5% |

0 / 659

|

No seats |

| 2005 | Roger Knapman | 603,298 |

2.2% |

0 / 646

|

No seats |

| 2010 | Lord Pearson | 919,546 |

3.1% |

0 / 650

|

No seats |

| 2015 | Nigel Farage | 3,881,099 |

12.6% |

1 / 650

|

Opposition |

| 2017 | Paul Nuttall | 593,852 |

1.8% |

0 / 650

|

No seats |

| 2019 | Patricia Mountain

(interim leader) |

22,817 |

0.1% |

0 / 650

|

No seats |

| 2024 | Nick Tenconi

(interim leader) |

6,530 |

0.01% |

0 / 650

|

No seats |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Partido de la Independencia del Reino Unido para niños

In Spanish: Partido de la Independencia del Reino Unido para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |