Poor relief facts for kids

In English and British history, poor relief means the ways that governments and churches tried to help people who were struggling with poverty. For hundreds of years, leaders had to decide who truly needed help and who should pay for it. As ideas about poverty changed, many different ways were tried to answer these questions. Since the early 1500s, laws about poverty in England changed a lot. What started as a system that often punished people became a complex system of government help and protection, especially after the welfare state was created in the 1940s.

Contents

Helping the Poor in Tudor Times (1485-1603)

In the late 1400s, the English Parliament started to deal with the growing problem of poverty. Their first focus was on punishing people who were called "vagabonds" (people who wandered without a home or job) and those who were begging.

In 1495, during the time of King Henry VII, a law called the Vagabond Act was passed. This law allowed officers to arrest "vagabonds" and other suspicious people. They would be put in stocks for three nights with only bread and water. After that, they were told to leave the town. This law didn't clearly define what a "vagabond" was. It didn't separate people who were just unemployed and looking for work from those who chose to wander. This made the law hard to use fairly.

When Monasteries Closed Down

The problem of poverty in England became much worse in the early 1500s because the population grew very quickly. More people meant fewer jobs for everyone. Things got even harder when Henry VIII decided to break away from the Pope and the Catholic Church. This led to the Dissolution of the Monasteries, where hundreds of rich religious places in England and Wales were closed down, and their wealth was taken by the King.

Before this, monasteries played a big role in helping the poor. They gave out money and food to those in need. When they closed, a lot of this help disappeared. Many hospitals, which were often like almshouses (places for the poor and sick) back then, also closed. This left many elderly and sick people without a place to live or care.

In 1531, the Vagabond Act was changed. A new law was passed that tried to help different groups of poor people. The sick, the elderly, and people with disabilities were allowed to get special permits to beg. But those who were out of work and looking for a job were still punished. Throughout the 1500s, a big reason for new laws was the fear that poor people might cause social unrest.

New Punishments for the Poor

This fear continued into the time of King Edward VI. In 1547, a new law called the Vagabonds Act 1547 brought in even harsher punishments. For a first offense, people could be forced to work as servants for two years and even be branded with a 'V' (for vagabond). Trying to run away could lead to lifelong slavery. However, it seems these very harsh punishments were rarely used. In 1550, these punishments were changed again because they were too extreme to be put into practice.

Parliament and Local Parishes

After the 1547 Act was changed, Parliament passed the Poor Act 1552. This law focused on using local church areas, called parishes, to raise money for the poor. Each parish had two "overseers" whose job was to collect money. They would "gently ask" for donations. If someone refused, they would meet with the local bishop, who would try to convince them to give. But even this didn't always work.

Since voluntary donations weren't enough, Parliament passed a new law in 1563. This law meant that if people still refused to donate, the bishop could bring them before the Justices. Refusing to give money could even lead to being put in prison until they paid. Still, people could decide how much they wanted to give.

A more organized system for donations was created by the Vagabonds Act 1572. After figuring out how much money was needed for the poor in each parish, the Justices of the Peace could decide how much money wealthy property owners in that parish had to give. This law finally turned these donations into a local tax.

The 1572 Act also brought in new punishments for vagabonds. These included having an ear "bored through" for a first offense and hanging for people who kept begging. Unlike the earlier harsh punishments, these were actually used quite often.

However, the 1572 Act was also the first time Parliament started to tell the difference between different types of vagabonds. It still punished able-bodied men "without land or master" who wouldn't take a job or explain how they made a living. But it specifically said that men who had left the military, servants who had been let go, or servants whose masters had died were not to be punished by this Act. However, the law didn't offer any way to support these people.

A New Way to Help

A system to help people who wanted to work but couldn't find a job was set up by the Act of 1576. This law allowed Justices of the Peace to give towns materials like flax or hemp so that poor people could be employed. It also allowed for "houses of correction" to be built in every county to punish those who refused to work. This was the first time Parliament tried to provide work as a way to deal with the growing number of "vagabonds."

Two years later, in 1578, more big changes were made. The Act of 1578 gave church officials, instead of Justices of the Peace, the power to collect the new taxes for the poor that were set up in 1572. This Act also gave more power to the church by saying that "vagrants were to be quickly whipped and sent back to their home parish by local constables." This made it faster to enforce the laws.

From Elizabethan Times to 1750

By the late 1500s, public leaders started to be more careful about who they helped. People who were truly in need, sometimes called the "deserving poor," were allowed to get help. But those who were seen as lazy were not. People who couldn't take care of themselves, like young orphans, the elderly, and those with mental or physical disabilities, were seen as deserving. However, those who were able to work but seemed too lazy were considered "idle" and not worthy of help.

Most poor relief in the 1600s came from people giving money or goods voluntarily, often in the form of food and clothing. Parishes sometimes gave land or animals. Some charities offered loans to help craftsmen or provided almshouses and hospitals.

The Act for the Relief of the Poor 1597 was the first full set of laws for poor relief. It created Overseers of the Poor and was later improved by the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601. This 1601 law was one of the most important achievements of Queen Elizabeth I's time and stayed in place until 1834. It made each parish responsible for helping the truly needy people in their own community. It taxed wealthier citizens to provide basic shelter, food, and clothing. However, parishes were not required to help people from outside their own community.

Because each parish was responsible for its own poor, some parishes were more generous than others. This caused poor people to move to parishes where they might get more help. To stop this, the Poor Relief Act 1662, also known as the Settlement Act, was put in place. This law allowed people to be forced back to their home parish if they moved. This law was not popular. To fix its problems, the Act of 1691 allowed people to gain settlement in new places. This could happen by owning or renting property above a certain value, paying parish taxes, completing a legal apprenticeship, or working for one year while unmarried.

The main ideas of this system were:

- Able-bodied poor people were to be given work in a House of Industry. They would be given the materials needed for this work.

- Lazy poor people and vagrants were to be sent to a House of Correction or prison.

- Poor children would become apprentices, learning a trade.

During the 1500s and 1600s, England's population almost doubled. New ways of doing business, especially in farming and manufacturing, started to grow, and trade with other countries increased a lot. But even with this growth, there still weren't enough jobs by the late 1600s. The population grew faster than the number of jobs, which led to rising prices. At the same time, wages went down, sometimes to about half of what they were a century before.

The ups and downs in the European trade of woolen cloth, which was England's main product and export, caused even more people in England to become poor.

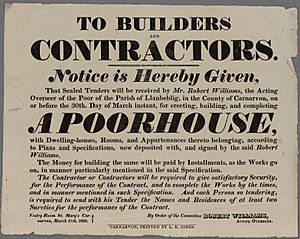

The Workhouse Test Act

In 1723, a law called the "Workhouse Test Act" was passed. It meant that if a person wanted to receive poor relief, they had to go into a workhouse and do a certain amount of work. This "test" was meant to stop people from asking for help if they didn't truly need it.

The Industrial Revolution and Poor Relief

By the mid to late 1700s, most of Britain was changing due to the Industrial Revolution. This meant new ways of making goods, new markets, and new ideas about social classes. Sometimes, factory owners hired children without paying them, which made poverty worse. The old Poor Laws encouraged children to become apprentices. But by the late 1700s, factory owners started hiring children to keep wages low, which meant fewer jobs for adult workers. For adults who couldn't find work, the workhouse became a place to get help.

Gilbert's Act

In 1782, a new poor relief law was suggested by Thomas Gilbert. It aimed to organize poor relief by county. Counties could set up workhouses together. However, these workhouses were only meant to help the elderly, sick, and orphans, not able-bodied people who could work. The sick, elderly, and weak were cared for in poorhouses, while able-bodied poor people were given help in their own homes.

The Speenhamland System

The Speenhamland system was a way to give "outdoor relief" (help given outside a workhouse) to reduce poverty in the countryside in the late 1700s and early 1800s. It was named after a meeting in 1795 in Speenhamland, Berkshire. Local leaders there created a system to help with the problems caused by very high grain prices. The price of grain likely went up because of bad harvests in 1795–96.

Under this system, families received extra money to bring their wages up to a certain level. This amount changed based on how many children a family had and the price of bread.

The New Poor Law of 1834

Indoor Relief vs. Outdoor Relief

After the Industrial Revolution began, the British Parliament changed the old Elizabethan Poor Law (1601) in 1834. They had studied the conditions of the poor. Over the next ten years, they started to stop giving "outdoor relief" (money given to people in their homes) and instead pushed poor people towards "indoor relief." This meant that people had to go into one of the workhouses to get help.

The Great Famine in Ireland

After the Poor Laws were changed in 1834, Ireland suffered a terrible potato blight from 1845 to 1849. This event, known as the Great Famine, caused about 1.5 million people to die. The effects of the famine lasted until 1851. During this time, many Irish people lost their land and jobs. They asked the British Parliament for help. This help usually came in the form of building more workhouses for "indoor relief." Some people argue that because the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a powerful empire at the time, it could have given more help, such as money, food, or rent support.

Around the same time, other parts of the United Kingdom also changed their poor laws. For example, in Scotland, the 1845 Scottish Poor Law Act updated the Poor Laws that had been in place since 1601.

See also

- Alms

- Debt relief

- Poverty in the United Kingdom

- Poverty reduction

- Public works

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |