Dissolution of the monasteries facts for kids

The dissolution of the monasteries was a big change in England, Wales, and Ireland between 1536 and 1541. During this time, Henry VIII closed down many Catholic monasteries, priories, convents, and friaries. He took their money and property, and decided what would happen to the people who lived and worked there.

King Henry VIII needed money for his wars. He got the power to close these religious houses from the Act of Supremacy in 1534. This Act made him the head of the Church in England, separate from the Pope in Rome. The monasteries were officially closed by two laws: the First Suppression Act (1535) and the Second Suppression Act (1539).

While Thomas Cromwell, a key minister for Henry VIII, oversaw the process, the idea to close the monasteries came from others. Thomas Audley and Richard Rich were important figures in making this happen.

Historian George W. Bernard said that closing the monasteries was one of the biggest changes in English history. There were almost 900 religious houses in England, with about 12,000 people living in them. This meant that about one in every fifty adult men was part of a religious order.

Contents

- Why Monasteries Were Closed

- Earlier Closures of Monasteries

- Changes in Europe

- How the Dissolution Happened

- King Henry Becomes Head of the Church

- Inspecting the Monasteries

- Reports and Closures

- The First Closures and Rebellions

- The Second Wave of Closures

- Closing the Friaries and Final Steps

- What Happened to Public Life?

- Effects on Arts and Learning

- Effects on Health and Education

- Effects on Religion

- Political Impact

- Ireland

- See also

Why Monasteries Were Closed

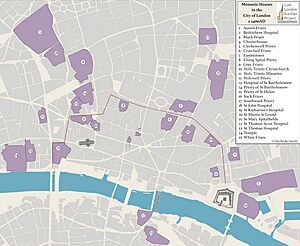

Most of the 625 religious communities that Henry VIII closed down had started in the 11th and 12th centuries. These houses were given land and money from churches. Because of this, religious houses in the 1500s controlled about two-fifths of all church jobs in England. They also had about half of all church income and owned about a quarter of the country's land. People even had a saying that if the abbot of Glastonbury married the abbess of Shaftesbury, their child would own more land than the King!

There were also about 200 houses of friars in England and Wales. Friaries were mostly in towns. Unlike monasteries, friars didn't own much land. They relied on donations from people and grew some of their own food.

The closing of monasteries in England and Ireland happened at a time when many church institutions in Europe were being challenged. This was part of the Reformation. In many parts of Europe, rulers who became Protestant also took over monastic property. However, in England, the changes were led by the King and the most powerful people, not by common people.

What Were the Complaints About Monasteries?

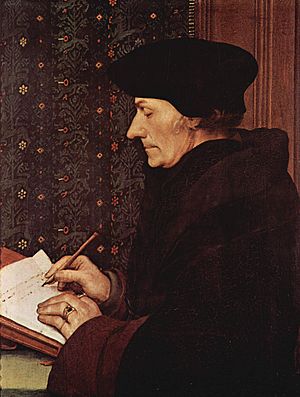

Many rulers and church leaders in Europe were unhappy with the state of religious life and the huge wealth of monasteries. Desiderius Erasmus, a famous scholar, criticized monasteries. He said they were too relaxed, focused too much on worldly things, wasted resources, and were superstitious. He thought it would be better if monks were under the direct control of bishops. Many bishops also felt that the money spent on monasteries could be better used to fund schools and train priests to serve ordinary people. They believed that caring for people was more important than just prayer and contemplation.

Erasmus had three main criticisms:

- Monks and nuns focused on their own rules and vows (like poverty, chastity and obedience) more than on God's teachings in the Gospels.

- Most monasteries were places for lazy people. They kept too much wealth for themselves and did little to help ordinary people spiritually.

- Monasteries made money from showing off relics and promoting pilgrimages to places where supposed miracles happened. Erasmus thought this was a trick played on people who easily believed such things.

Historian David Knowles summarized that there were too many religious houses. He also believed that monks owned too much wealth, which was not good for them or the economy.

How Did Reforms Start?

People still went on pilgrimages to holy sites until Henry VIII stopped them in 1538. However, the closing of monasteries didn't change much about how people practiced religion in their local churches. The religious changes in England in the 1530s were different from what Protestant reformers wanted. People often didn't like these changes.

Cardinal Wolsey had tried to make some small reforms in the English Church as early as 1518. But reformers were frustrated that things weren't changing fast enough. Henry VIII wanted to fix this. In 1529, Parliament passed laws to stop abuses in the Church. These laws limited fees for wills and burials, tightened rules for criminals seeking sanctuary, and reduced the number of church jobs one person could hold. These actions showed that the King's control over the Church would bring "religious reformation" where the Pope's power had failed.

The monasteries were next. J. J. Scarisbrick, a biographer of Henry VIII, said that English monasteries were a "huge and urgent problem." He felt that strong action was needed.

Stories of bad behavior in monasteries, collected by Thomas Cromwell's visitors, might have been exaggerated. But most religious houses in England and Wales had stopped being important spiritual centers. Only a few orders, like the Carthusians and Observant Franciscans, were still strict. Most monks and nuns were comfortable, not living a strict religious life. Many monasteries were less than half full.

From 1534, Cromwell and King Henry looked for ways to get church money for the Crown. They argued that much of the church's money had originally been taken from the King. Rulers across Europe faced money problems, especially for armies and forts. Many ended up taking wealth from monasteries. Monastic wealth was seen as too much and not being used well, making it tempting for rulers who needed money.

The official actions focused on monasteries and their property. Closing them caused some public anger. However, friaries were closed almost as an afterthought. Monasteries usually supported themselves from their lands and were often liked locally. Friars, who relied on donations, were sometimes less popular.

Earlier Closures of Monasteries

Before Henry VIII, English kings had already closed religious houses for over 200 years. The first cases were "alien priories." After the Norman Conquest, some French religious groups owned property in England.

Because England and France were often at war, English governments didn't like money going to France from these priories. They also didn't like foreign church leaders having power over English monasteries.

King Henry V closed about ninety smaller alien priories in 1414. Their properties went to the Crown. Some were kept, some were given or sold to Henry's supporters, and others were used for new monasteries or schools. The Pope approved these closures.

In the Middle Ages, religious houses were seen as connected to their property, not just the monks and nuns living there. If a house's property was taken, the house stopped existing. The original founders or their heirs had rights to the property. If a community failed, the property would go back to the founder's heirs or the Crown. The Crown often claimed these properties.

Bishops also started closing small, poor, or indebted monasteries in the 15th century. They used the money to fund universities. For example, John Alcock, Bishop of Ely, closed St Radegund's Priory, Cambridge to start Jesus College, Cambridge in 1496.

In 1522, John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, closed two women's monasteries to help St John's College, Cambridge. That same year, Cardinal Wolsey closed St Frideswide's Priory (now Oxford Cathedral) to create Christ Church, Oxford. In all these cases, the remaining monks and nuns moved to other houses of their orders.

Most people agreed that the English church needed reform. This would mean combining monks and nuns into fewer, larger houses. This would also free up monastic money for other religious, educational, and social uses.

However, this was hard to do. Monks and nuns didn't want to move. Local leaders didn't like the changes. Also, monks and nuns often had their own money, which gave them freedom from strict rules. Many religious houses were not following their rules strictly.

The King supported these reforms, but progress was slow. In 1532, the priory of Christchurch Aldgate was closed without a jury decision. Thomas Audley, the Lord Chancellor, suggested that such closures should be made legal by a special Act of Parliament.

Changes in Europe

While England was dealing with these issues, other parts of Europe were also changing. In 1521, Martin Luther wrote that monastic life had no basis in the Bible and was wrong. He said that monastic vows were meaningless. Many friars in his order agreed and left their monasteries to marry.

News of these events spread quickly. In Sweden, King Gustav Vasa was allowed to take monastic lands to increase royal income in 1527. Monasteries were forbidden from taking new members, and existing members could leave. In Denmark–Norway, King Frederick I did something similar in 1528.

In Switzerland, the city of Zürich closed all monasteries in its territory in 1524, using their money for education and the poor. Basel followed in 1529, and Geneva in 1530.

In France and Scotland, kings took monastic income in a different way. They appointed people, often lay courtiers, to be "commendatory abbots." These people would receive much of the monastery's income without being monks. This way, the French and Scottish kings gained a lot of money from monasteries with the Pope's blessing.

The English government, especially Thomas Cromwell, surely noticed these events. However, Henry VIII was more influenced by thinkers like Desiderius Erasmus and Thomas More. They criticized monastic practices like repetitive prayers, superstitious pilgrimages, and the accumulation of wealth. Henry seemed to agree with these views.

How the Dissolution Happened

King Henry Becomes Head of the Church

When the Pope refused to annul his marriage, Henry declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England in 1531. He then passed laws to make this official. An Act in 1533 stopped clergy from appealing to Rome. All church fees that used to go to Rome now went to the King. The English clergy agreed that the King was the head of the Church.

This meant that any resistance from monasteries to the King's authority would be seen as treason. Most religious houses agreed to the King's supremacy. However, some, like the Carthusian monks, Observant Franciscan friars, and Bridgettine monks and nuns, resisted. These were known for their strict religious life. The government tried hard to make them agree. Those who refused were imprisoned or executed for treason.

Inspecting the Monasteries

In 1534, Cromwell ordered a survey of all church property in England and Wales, including monasteries. This was to find out how much tax the Church could pay. At the same time, Henry gave Cromwell power to "visit" all monasteries. This was to check their religious life and make sure they obeyed the King, not the Pope.

Cromwell sent special commissioners to inspect the monasteries. These commissioners, like Richard Layton and Thomas Legh, were often critical of monastic life and disliked relics. They interviewed each person in the monastery, asking them to confess wrongdoings and report on others. The commissioners knew that Cromwell wanted to hear about problems. While they might have exaggerated, they didn't seem to invent stories.

Reports and Closures

In late 1535, the commissioners sent reports to Cromwell about the problems they found. They also sent bundles of items like "miraculous wimples" that monks and nuns had lent out for money. Many monks and nuns chose to leave their vows and start new lives.

The commissioners found that some houses had too many problems or too few members. They suggested closing them. The King then needed a legal way to do this. Parliament passed the Suppression of Religious Houses Act 1535 (also called the "Dissolution of the Lesser Monasteries Act") in 1535. This law allowed the King to close monasteries with an annual income of less than £200. However, the King could choose to spare some of these houses.

Many smaller monasteries tried to avoid closure by paying large fines. About 80 houses were spared. Only about 243 houses were actually closed at this time. The law stated that the property of closed houses would go to the Crown. Cromwell created a new government office, the Court of Augmentations, to manage this property.

Local commissions visited the smaller houses chosen for closure in 1536. They made lists of assets and offered pensions to monastic leaders who cooperated. Most monks and nuns were given a choice: leave religious life with a small payment or move to a larger, still-open monastery. Most chose to continue religious life. However, finding new homes for them was harder than expected.

Two monasteries, Norton Priory and Hexham Abbey, tried to fight the commissioners. Henry saw this as treason. The leaders of Hexham were executed for their involvement in the Pilgrimage of Grace, a rebellion.

The First Closures and Rebellions

The first round of closures caused a lot of anger, especially in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire. This led to the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536. Some monasteries that had been spared joined the rebels. This made Henry VIII see monasteries as a threat.

The law stated that if a monastery's leader was found guilty of treason, all its property would go to the Crown. Cromwell had planned this. The First Suppression Act had said that the goal was reform, not total closure. Many historians believe that Henry still wanted to reform, but also planned to take action against richer monasteries later.

For most of 1537, there was a pause in closures. Monasteries tried to improve their discipline. Many also leased out their lands and offered jobs and payments to local important people. This reduced the money the Crown would get later, but it also made local leaders more likely to support the dissolutions.

By late 1537, it became clear that the government planned to close all monasteries. However, they wanted this to happen through "voluntary surrender" by the monastic leaders, rather than by law. Furness Abbey in Lancashire, whose monks were involved in the Pilgrimage of Grace, voluntarily surrendered to avoid treason charges. From then on, most closures were "voluntary." Monks were offered pensions if they cooperated. This put pressure on abbots and priors to surrender.

From early 1538, Cromwell pushed monastery leaders to apply for surrender. The government still publicly said that well-run houses could survive. But Cromwell also warned against hiding valuables, which could be seen as treason.

The Second Wave of Closures

In 1538, many monasteries applied to surrender. Cromwell sent local commissioners to oversee the sales of monastic goods and buildings. They also made sure former monks and nuns received pensions and payments. This process was much faster and easier this time.

Existing tenants of monastic lands kept their leases. Lay people who held jobs or received payments from monasteries continued to get their income. Older, sick, or disabled monks and nuns received more generous pensions. The goal was to ensure no one was left without support. Some monastic servants even received a year's wages.

The land and income from the monasteries went to the Court of Augmentations. This court paid out the pensions. Monks typically received about £5 per year, while nuns received about £3 per year. This was a good amount of money at the time. However, nuns had fewer options for work and were not allowed to marry during Henry's reign. Many returned to live with their families.

Once it was clear that all monasteries would close, the future of the ten monastic cathedrals was questioned. Some were closed, but eight needed to continue. The plan was to turn them into "collegiate churches" with secular priests, like the one at Stoke-by-Clare.

In 1538, the monastic cathedral of Norwich surrendered and became a collegiate church. This meant fewer clergy, but they would focus on preaching and education. Many people, including Cromwell, hoped that some great monasteries would be refounded as colleges.

When the Second Suppression Act was passed in 1539, it allowed the King to create new bishoprics and collegiate cathedrals from existing monasteries. However, Henry VIII needed money for fortifications due to a fear of invasion. So, the number of new foundations was greatly reduced. Only six abbeys became cathedrals for new dioceses, and two others became non-cathedral colleges.

Even in late 1538, Cromwell thought some nunneries might be allowed to continue if they were well-run. Godstow Abbey was one such place, known for educating girls. But this only lasted a year. Godstow and all other nunneries were closed in November 1539, as Henry wanted none to continue.

Closing the Friaries and Final Steps

The friaries were not part of the earlier laws. In the 1300s, there were about 5,000 friars in England. By the 1500s, their numbers had dropped to less than 1,000. Their buildings were often falling apart or rented out. Most friars were living outside their friaries and supporting themselves with paid jobs.

By early 1538, people expected friaries to close. Cromwell sent Richard Yngworth, a bishop, to get the friars to surrender. Yngworth made them follow strict rules again, which meant that if they didn't surrender, they would likely become homeless and starve. Once they surrendered, friars were released from their vows and given a small payment. They were also given permission to become secular priests.

Yngworth had no power to save the friary churches, even though many were still used by local people. Most of these churches were quickly sold off. Today, very few friary churches remain standing.

In April 1539, Parliament passed a new law that made all voluntary surrenders legal. By then, most monasteries in England and Wales had already been closed. Some still resisted. That autumn, the abbots of Colchester, Glastonbury, and Reading were executed for treason. Their monasteries were closed, and their monks received small pensions.

St Benet's Abbey in Norfolk was the only abbey in England that was not formally dissolved. Its property was transferred to the Bishop of Norwich. The last two abbeys to be closed were Shap Abbey in January 1540 and Waltham Abbey in March 1540.

What Happened to Public Life?

When monasteries surrendered, it meant the end of religious life for their members, unless they went into exile. Some groups of former monks or nuns lived together, but they didn't continue their religious practices openly. The laws were about taking property, not about stopping religious life. However, it would have been dangerous for former communities to continue secretly.

Local officials were told to make sure that parts of abbey churches used by local parishes could continue to be used. As a result, parts of 117 former monasteries are still used as parish churches today. Fourteen former monastic churches also survived as cathedrals. Some wealthy people or parishes bought entire monastic churches to use as new parish churches. Many others bought monastic wood carvings, choir stalls, and stained-glass windows.

The abbots' homes were often turned into country houses by their new owners. Other monastic buildings were converted into mansions. The most valuable material in monastic buildings was often the lead on the roofs. Buildings were sometimes burned down to get the lead. Stone and slate were also sold.

Cromwell had also started a campaign against "superstitions." This meant that old and valuable items from pilgrimages and saint worship were taken and melted down. The tombs of saints and kings were looted, and their relics were destroyed. Great abbeys like Glastonbury and Walsingham, which had been pilgrimage sites for centuries, were left in ruins. However, there wasn't a general policy to destroy everything. Buildings often fell apart from neglect or were used for building materials.

After providing for new cathedrals and other needs, the Crown gained about £150,000 per year. About £50,000 of this was used for monastic pensions. Cromwell wanted this wealth to be regular government income. But after Cromwell's fall in 1540, Henry needed money for his wars. So, monastic property was sold off quickly. By 1547, this brought in £90,000 per year.

The land was not auctioned. Instead, the government responded to requests to buy it. Many buyers were founders or patrons of the houses. They were usually leading nobles, local powerful families, and gentry. They wanted to increase their family's status and land. Owning manorial estates was important for status, and this was a rare chance to buy them. The Court of Augmentations kept enough land to pay pensions. As pensioners died, more property became available. The last surviving monks received pensions until the early 1600s.

The dissolution didn't change much for English parish churches. Parishes that used to pay their tithes to a monastery now paid them to a lay person. Rectors and vicars stayed in their jobs, and their incomes and duties didn't change. Congregations that shared monastic churches continued to do so, with the monastic parts often walled off and ruined.

Many churches also had "chantries," which were funds to pay a priest to say Mass for the souls of donors. These continued for a while. There were also over a hundred collegiate churches that maintained choral worship. These survived Henry VIII's reign but were closed under his son, Edward VI, in 1547. Many former monks had become chantry priests, so they experienced dissolution twice.

Effects on Arts and Learning

The destruction of monastic libraries was a great cultural loss. Worcester Priory had 600 books when it was dissolved, but only six are known to exist today. A library of 646 books at the Augustinian Friars in York was destroyed, with only three known survivors. Some books were destroyed for their valuable covers, others were sold by the cartload. Much was lost, especially handwritten books of English church music.

John Bale wrote in 1549: "A great number of them which purchased those superstitious mansions, reserved of those library books, some to serve their jakes, some to scour candlesticks, and some to rub their boots. Some they sold to the grocers and soapsellers."

Effects on Health and Education

The 1539 Act also closed religious hospitals, which cared for older people. A few, like Saint Bartholomew's Hospital in London, were spared, but most closed. Their residents were given small pensions.

Monasteries also provided free food and help for the poor. Some argue that losing this charity, about 5% of monastic income, led to more beggars in England. However, others, like G. W. O. Woodward, argue that monastic charity was only a small part of the problem. He says that even if monasteries had stayed, they couldn't have handled the poverty caused by population growth and inflation in the 1500s.

Monasteries provided schooling for their new members and sometimes for other young students. This educational resource was lost. However, grammar schools run by monasteries were often refounded with more money. Some were refounded by the King for new cathedrals, and others by private individuals. Five of the six monastic colleges at Oxford and Cambridge universities survived as refoundations.

Many new almshouses and charities were founded by wealthy people later. However, it's estimated that overall charitable giving in England didn't return to pre-dissolution levels until 1580. Before the closures, monasteries owned about 2 million acres of land, over 16% of England.

Effects on Religion

Some argue that closing English monasteries led to a decline in contemplative spirituality in Europe. However, in the new cathedrals, the daily singing of the Divine Office continued as public worship. Many former monks and friars became parish clergy. The number of new ordinations dropped sharply after the dissolution.

In 1549, former monks and nuns were allowed to marry. Many did, but under Queen Mary, they were forced to separate and lost their pensions. When Elizabeth I became queen, these former monks and friars (who got their wives and pensions back) became a key part of the new Anglican church. They helped keep religious life going until a new generation of clergy was trained.

Before the dissolution, there were no special schools to train parish clergy. Monasteries often sponsored candidates for ordination. With the monasteries gone, new ways to sponsor clergy were needed. The laws allowed lay and church leaders who took over monastic property to provide sponsorship. However, it took time for these new arrangements to work.

The number of new clergy dropped greatly for 20 years. This led to many vacant church positions. However, a long-term result of the dissolution was that parish clergy in England became a more educated and professional group.

While Henry VIII said the increased wealth would fund religious, charitable, and educational institutions, only about 15% of the monastic money was used for these purposes. This included refounding eight of nine former monastic cathedrals and creating six new bishoprics with their cathedrals, choirs, and grammar schools. It also involved refounding some monastic institutions as secular colleges and funding professorships at Oxford and Cambridge universities.

The Court of Augmentations kept about a third of the monastic income to pay pensions. Just over half of the remaining property was sold. Henry gave very little property away for free. The English dissolutions created fewer new educational institutions compared to other parts of Protestant Europe. However, former monks and nuns were treated more kindly, and the system for paying their pensions was very efficient.

Political Impact

The closing and destruction of monasteries and shrines was very unpopular in many areas. In northern England, especially Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, it led to a popular uprising called the Pilgrimage of Grace. This rebellion threatened the King for several weeks in 1536. There were rumors that the King would also tax livestock and strip parish churches. The rebels demanded that Cromwell be removed and that the monasteries not be dissolved. Henry made promises to calm the unrest, then quickly executed some of the leaders.

When Henry VIII's Catholic daughter, Mary I, became queen in 1553, she hoped to bring back religious life. Westminster Abbey became a monastery again. The Bridgettine nuns and Observant Franciscans, who had left England, returned to their former houses. A small group of Carthusians also returned. However, Mary found it hard to persuade former monks and nuns to resume religious life. Plans to restore abbeys like Glastonbury failed because there weren't enough volunteers.

All the refounded houses were on property that the Crown still owned. Mary's supporters would not give back their monastic lands. Parliament was strongly against bringing back the "mitred" abbeys, which would have given church leaders a majority in the House of Lords. People also worried that bringing back religious communities might question the legal ownership of monastic land.

In 1554, Cardinal Pole, the Pope's representative, allowed the new owners to keep the former monastic lands. When Mary died in 1558 and Elizabeth I became queen, five of the six revived communities left England again. An Act of Elizabeth's first parliament dissolved the refounded houses. Within 20 years, monastic life had effectively ended in England.

Ireland

The closures in Ireland were very different from England and Wales. In 1530, Ireland had about 400 religious houses. Unlike England, friaries in Ireland were thriving in the 1400s, with popular support and new buildings. Irish monasteries, however, had seen a big drop in members.

Henry's direct power in Ireland only covered the area around Dublin called the Pale. Outside this area, he had to make deals with local clan chiefs and lords.

Despite this, Henry wanted to close monasteries in Ireland. In 1537, he passed a law in the Irish Parliament to do this. There was strong opposition, and only sixteen houses were closed. From 1541, as part of the Tudor conquest of Ireland, Henry continued to push for more closures. He often gave monastic property to local lords in exchange for their loyalty. So, Henry gained little wealth from Irish houses.

By Henry's death in 1547, about half of the Irish houses had been closed. But many continued to resist until the reign of Elizabeth I, and some in western Ireland were active until the early 1600s. In 1649, Oliver Cromwell led an army to Ireland and systematically destroyed former monastic houses. However, some sympathetic landowners later housed monks or friars near ruined religious houses, allowing them to continue secretly.

|

See also

In Spanish: Disolución de los monasterios para niños

In Spanish: Disolución de los monasterios para niños

- Cestui que

- Charter of Liberties

- Compendium Competorum

- Dissolution (Sansom novel)

- List of monasteries dissolved by Henry VIII of England

- Little Jack Horner, a children's rhyme allegedly based on the episode.

- Religion in the United Kingdom

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |