History of the Republic of Ireland facts for kids

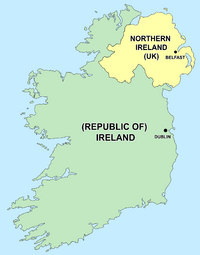

The Irish state, officially called the Republic of Ireland, began in 1919 as the 32-county Irish Republic. In 1922, it left the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland under the Anglo-Irish Treaty. It then became the Irish Free State. This state included 32 counties, but six counties in the north, controlled by Unionists, chose to stay with the UK.

The 1937 constitution changed the state's name to 'Ireland'. In 1949, the 26 counties of the state officially became a republic under the Republic of Ireland Act 1948. This ended its connection to the British Commonwealth. In 1973, the Republic of Ireland joined the European Communities (EC), which later became the European Union (EU).

When the Irish Free State was founded, it faced a civil war. This war was between Irish nationalists who supported the Treaty and those who opposed it. The pro-Treaty side, known as Cumann na nGaedheal, won the war and later elections. They governed until 1932. Then, the anti-Treaty group, Fianna Fáil, won an election and took power peacefully. Even with its difficult start, the Irish state has always been a democracy. In the 1930s, many links with Britain were removed. Ireland's neutrality in the Second World War also showed its independence from Britain in foreign policy.

Economically, Ireland has had ups and downs. At independence, it was one of Europe's richer countries per person. However, it also had problems from British rule, like unemployment, people leaving the country, uneven development, and a lack of local industries. For much of its history, the state tried to fix these issues. Many people left Ireland in the 1930s, 1950s, and 1980s, when the economy grew very little.

In the 1930s, Fianna Fáil governments tried to create Irish industries. They used government help and taxes on foreign goods to protect these new businesses. In the late 1950s, these policies changed. Ireland started to favor free trade with some countries and encouraged foreign companies to invest with low taxes. This expanded when Ireland joined the European Economic Community in 1973. In the 1990s and 2000s, Ireland had a huge economic boom called the Celtic Tiger. The country's wealth grew faster than many other European countries. More people moved to Ireland than left, bringing the population to over 4 million. However, since 2008, Ireland has faced a big crisis in its banks and government debt. This economic downturn made the global recession worse for Ireland.

From 1937 to 1998, the Irish constitution said that Northern Ireland was part of its national territory. But the state also fought against armed groups, mainly the Provisional Irish Republican Army, who tried to unite Ireland by force. This happened in the 1950s, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, and continued on a smaller scale. Irish governments also tried to find a peaceful solution to the conflict in Northern Ireland, known as the Troubles, from 1968 to the late 1990s. The British government officially allowed the Irish government to be part of the Northern negotiations in the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985. In 1998, as part of the Good Friday Agreement, the Irish constitution was changed. It removed the claim to Northern Ireland. Instead, it offered Irish citizenship to all people on the island if they wanted it.

Contents

How Ireland Became Independent

Steps Towards Independence and Division

From 1801 until December 6, 1922, all of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. But from the 1880s, many Irish people wanted more control over their own affairs, a system called Home Rule. A smaller group, like the Irish Republican Brotherhood, wanted full independence.

In 1912–1913, the British government suggested a Home Rule law. This worried Unionists in the north, who formed an armed group called the Ulster Volunteers to resist it. Nationalists then created their own group, the Irish Volunteers. Because of this tension, the idea of dividing Ireland was discussed. In 1914, the UK Parliament passed a Third Irish Home Rule Bill, but it was put on hold until after World War I.

The nationalist leader John Redmond supported Britain in the war, and many Irishmen joined the British Army. However, the war and the delay of Home Rule made some Irish nationalists more radical. In 1916, a group of activists in Dublin led an uprising for independence, known as the Easter Rising. The rebellion failed quickly, but the execution of its leaders and the arrest of many nationalists made the public very angry. After the Rising, another attempt to solve the Home Rule issue failed. Finally, Britain's plan to force Irishmen into the army (see Conscription Crisis of 1918) caused widespread resistance. This also made the Irish Parliamentary Party, who supported Britain, lose public trust.

All these events led to strong support for Sinn Féin. This party was led by people from the Easter Rising and wanted an independent Irish Republic. In the Irish general election, 1918, Sinn Féin won most of the seats. Their elected members refused to go to the UK Parliament in Westminster. Instead, they met in Dublin as a new parliament called "Dáil Éireann". They declared the "Irish Republic" existed and set up a government to challenge British rule.

The first meeting of the Dáil happened at the same time as a shooting of two policemen in Tipperary. This event is seen as the start of the Irish War of Independence. From 1919 to 1921, the Irish Volunteers (now called the Irish Republican Army, or IRA) fought a guerrilla warfare against the British army and police. The violence started slowly but grew sharply. In the first six months of 1921 alone, 1,000 people died. The main political leader was Éamon de Valera, the President of the Republic. But he spent much of the war in the United States, raising money. In his absence, Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy became important leaders of the IRA.

Several attempts to end the conflict failed. In 1920, the British government proposed the Government of Ireland Act 1920. This law divided Ireland into two self-governing areas: Northern Ireland (six northeastern counties) and Southern Ireland (the rest of the island). Southern republicans did not accept this. Only Northern Ireland was set up under this Act in 1921. The political area of Southern Ireland was replaced in 1922 by the Irish Free State.

After more failed talks in December 1920, the fighting ended in July 1921 with a truce between the IRA and the British. Formal peace talks then began.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty

Negotiations between British and Irish teams led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed on December 6, 1921. The Irish team was led by Michael Collins. The British team, led by David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill, would give Ireland more independence but not a full republic. Towards the end, Lloyd George threatened "immediate and terrible war" if the Irish did not accept the terms.

The Treaty created a new system of Irish self-government called "dominion status". The new state was named the Irish Free State. It was much more independent than a Home Rule parliament would have been. It had its own police and army, and controlled its own taxes. However, there were some limits. It remained a dominion of the British Commonwealth. Members of its parliament had to promise loyalty to the British monarch. Britain also kept three naval bases, known as the Treaty Ports. Also, the Irish state had to pay pensions to former British civil servants, except for the police force, which was disbanded.

There was also the issue of partition, which the Treaty confirmed. Northern Ireland was included in the Treaty, but Article 12 gave it the option to leave within a month. So, for three days in December 1922, the new Irish Free State theoretically included all of Ireland. But Northern Ireland was already a working self-governing area and formally left the Irish Free State on December 8, 1922.

Because of these limits to its independence and because the Treaty ended the Republic declared in 1918, the Sinn Féin movement, the Dáil, and the IRA were deeply divided over accepting the Treaty. Éamon de Valera, the President of the Republic, was the main leader of those who rejected it. He objected, among other things, that Collins had signed it without the Dáil's permission.

The Civil War

The Dáil narrowly approved the Anglo-Irish Treaty on January 7, 1922, by a vote of 64 to 57. Éamon de Valera and some other cabinet members resigned in protest.

The pro-Treaty leaders, Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith, formed a Provisional Government. They began setting up the Irish Free State. They started recruiting for a new army, made of pro-Treaty IRA units. They also began recruiting for a new police force, the Civic Guard, to replace the old police.

However, most of the IRA, led by Rory O'Connor, opposed the Treaty. They believed it ended the Irish Republic they had sworn to defend. They also disliked the oath of loyalty to the British monarch. In March 1922, the IRA held a meeting where they rejected the Dáil's authority and gave it to their own Army Council. In April, O'Connor led anti-Treaty forces to occupy public buildings in Dublin, like the Four Courts. Éamon de Valera, though not leading the anti-Treaty IRA, also led political opposition in a new party called Cumann na Poblachta.

With two rival Irish armies, a civil war seemed likely in the spring of 1922. Three events started it. First, the election on June 18, 1922, which the pro-Treaty Sinn Féin won, giving the Free State public support. Second, the killing of a retired British general in London by Irish republicans. The British government thought the anti-Treaty IRA was responsible and told Collins to act or face British military action. Third, the IRA in the Four Courts kidnapped a Free State general. These events forced Collins's government to attack the anti-Treaty positions in Dublin. They succeeded after a week of fighting in July 1922. Éamon de Valera supported the anti-Treaty IRA after the fighting began.

A military push secured Free State control over other major towns by early August. Despite losing in open battles, the IRA regrouped and started a guerrilla campaign. They saw this as a fight to restore the Irish Republic. The war continued as a guerrilla conflict until April 1923. In August 1922, the Free State lost its two main leaders. Michael Collins was killed in an ambush on August 22, 1922, and Arthur Griffith died a week earlier. W. T. Cosgrave took control. The Irish Free State officially began on December 6, 1922.

The anti-Treaty IRA, led by Liam Lynch, used the same guerrilla tactics as they had against the British. But without as much public support, they were less effective. By late 1922, the Irish National Army controlled all major towns. The IRA's campaign became small-scale attacks. About 12,000 anti-Treaty fighters were held by the Free State. The war also saw harsh actions from both sides. The Free State executed 77 prisoners and unofficially killed over 100 more. Anti-Treaty forces killed one pro-Treaty politician and wounded others. But the Free State's tactics weakened the anti-Treaty forces by April 1923.

Liam Lynch's death in April led the anti-Treaty IRA, under Frank Aiken and urged by de Valera, to call a ceasefire and "dump arms" (give up weapons). There was no negotiated end to the war.

The Civil War caused deep bitterness among Irish nationalists. It also created the two main political parties of independent Ireland in the 20th century. About 2,000 people died, a number similar to those killed in the War of Independence.

Ireland from 1922 to 1939

After the Civil War, elections were held, and anti-Treaty Sinn Féin was allowed to take part. Even though many of their candidates, including Éamon de Valera, were in prison, they won about one-third of the votes. However, the pro-Treaty side, organized as Cumann na nGaedheal, won a clear majority. They formed the government until 1932.

The Cumann na nGaedheal governments, led by WT Cosgrave, were very traditional. Their main goal was to set up the state's basic systems after the Civil War, rather than to make big social or political changes. The Irish Civil Service largely continued from the British system. The new government focused on balancing the budget. The Free State printed its own money, but its value was linked to British currency until the 1970s.

While the British had given much power to local governments, the Free State quickly reduced the powers of County Councils. They replaced them with unelected County managers. This was partly because some councils supported the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War. A major success of the Cumann na nGaedheal governments was creating the police force, the Garda Síochána. It was unarmed and politically neutral, which helped it avoid the bitterness of the civil war.

Economically, the Cosgrave government aimed to support Irish farming exports. They did this by making farms more efficient and improving product quality. The first Minister for Finance, Ernest Blythe, cut public spending to reduce debt. Cumann na nGaedheal governments did not prioritize social services. One important project was the Shannon hydroelectric scheme, which gave Ireland its first independent source of electricity.

Even after the last Civil War prisoners were released in 1924, the Free State kept strong emergency powers. These allowed them to hold and even execute political opponents. These powers were used after the IRA killed Minister Kevin O'Higgins in 1927.

Fianna Fáil Takes Power

The political group that opposed the Treaty reformed in 1926 as Fianna Fáil. Only a small group of hardline republicans remained in Sinn Féin and the IRA, refusing to accept the state's authority. Fianna Fáil first refused to take their seats in the Dáil. However, they entered parliament in 1927, partly to distance themselves from the killing of Kevin O'Higgins.

Cumann na nGaedheal was popular at first for setting up the state. But by 1932, their traditional economic policies and continued actions against anti-Treaty Republicans became unpopular. Fianna Fáil won the 1932 election. Their plan was to develop Irish industry, create jobs, provide more social services, and cut remaining ties with the British Empire. In 1932, Fianna Fáil formed a government with the Labour Party. A year later, they won a full majority. They would govern without interruption until 1948 and for much of the rest of the 20th century.

One of Fianna Fáil's first actions was to make the IRA legal again and release imprisoned republicans.

Economic Nationalism and Trade War

Fianna Fáil's economic plan was very different from Cumann na nGaedheal's. Instead of free trade, Fianna Fáil wanted to build Irish industries. They protected these industries from foreign competition with tariffs (taxes on imports) and government help. They also made foreign companies have a certain number of Irish members on their boards. They set up many state-owned companies, like the Electricity Supply Board. While this state-led approach had some good results, many people still left Ireland, with up to 75,000 going to Britain in the late 1930s.

In their pursuit of economic independence, Fianna Fáil also started a Anglo-Irish Trade War with Britain in 1933. They refused to keep paying back "Land Annuities," money Britain had provided for Irish farmers to buy land. Britain responded by raising taxes on Irish farm products, hurting Ireland's exports. De Valera then raised taxes on British goods coming into Ireland. This conflict mainly hurt cattle farmers, who could no longer sell their cattle cheaply in Britain.

The dispute with Britain ended in 1939. Half of the land annuity debt was cancelled, and the rest was paid as a lump sum. Britain also returned the Treaty ports to Ireland. Irish control over these bases allowed Ireland to remain neutral in the upcoming Second World War.

Ireland's Constitutional Status

From 1922 to 1937, the Free State was a constitutional monarchy. The British monarch was the head of state, and their representative was called the Governor-General. The Free State had a parliament and a cabinet called the "Executive Council". The head of government was called the President of the Executive Council.

In 1931, the UK Parliament passed The Statute of Westminster. This law gave legislative independence to six British Dominions, including the Irish Free State. In 1932, after Éamon de Valera and Fianna Fáil won the election, the 1922 constitution was changed. A new constitution was written by de Valera's government and approved by voters.

On December 29, 1937, the new "Constitution of Ireland" came into effect. It renamed the Irish Free State to "Éire" or "Ireland". The Governor-General was replaced by a President of Ireland. A new, more powerful prime minister, called the "Taoiseach", was created. The Executive Council was renamed the "Government". Even with a president, the new state was not a full republic. The British monarch still theoretically reigned as King of Ireland for international matters. The President of Ireland had symbolic roles only within the state.

Northern Ireland's Status

The Anglo-Irish Treaty said that if Northern Ireland chose not to be part of the Free State, a Boundary Commission would redraw the borders. Irish people hoped this would allow nationalist areas in Northern Ireland to join the Free State. The commission focused on economic factors rather than people's wishes. In 1925, the commission suggested giving some small Free State areas to Northern Ireland. For various reasons, the governments agreed to keep the original border. In return, Britain dropped Ireland's obligation to share in paying Britain's Imperial debts. The Dáil approved the boundary by a large vote.

World War II, Neutrality, and "The Emergency" 1939–1945

When World War II started, Ireland and de Valera's government faced a difficult choice. Britain and later the USA pressured Ireland to join the war or at least let the Allies use its ports. However, some Irish people felt that full independence had not yet been achieved and strongly opposed any alliance with Britain. Because of this, de Valera made sure Ireland remained neutral throughout the war, which was officially called "Emergency". Ireland's decision to be neutral was influenced by memories of past conflicts and its lack of military readiness.

The remaining parts of the IRA, which had split many times, started bombing campaigns in Britain and some attacks in Northern Ireland. They wanted to force Britain to leave Northern Ireland. Some IRA leaders even sought help from Nazi Germany. De Valera saw this as a threat to Irish neutrality and national interests. He held all active IRA members and executed several.

Behind the scenes, Ireland worked with the Allies. In 1940, the government agreed with Britain that it would accept British troops if Germany invaded Ireland. There was a German plan to invade Ireland, but it was never carried out. Also, Irish firefighters went to Northern Ireland to help after German bombings in Belfast in 1941.

There were other examples of cooperation. German pilots who crashed in Ireland were held, while Allied airmen were returned to Britain. There was also sharing of information. For example, the date of the D-Day landings was decided based on weather reports from Ireland. It is estimated that between 50,000 and 150,000 men from Ireland fought in the war, roughly split between Northern Ireland and the southern state.

However, after Adolf Hitler's death, de Valera, following diplomatic rules, offered condolences to the German ambassador. This was a controversial act.

Economically, the war was tough for Ireland. Industrial production dropped by 25%. Unlike World War I, when Irish farmers made money selling food to Britain, in World War II, Britain set strict price controls on Irish farm imports. Imports to Ireland dried up, leading to a focus on self-sufficiency in food and strict rationing, which lasted until the 1950s. Despite this, because of its neutrality, Ireland avoided the destruction and hardship faced by countries involved in the war in Europe.

1949 – Becoming a Republic

On April 18, 1949, the Republic of Ireland Act 1948 came into force. This law described Ireland as the Republic of Ireland, but it did not change the country's name. The international duties previously held by the King were now given to the President of Ireland, who clearly became the Irish head of state. Under the rules of the Commonwealth at the time, declaring a republic automatically ended Ireland's membership in the British Commonwealth. Unlike India, which became a republic soon after, Ireland chose not to rejoin the Commonwealth.

Although a republic since 1949, the old law that created the Kingdom of Ireland was not fully cancelled until 1962. However, long before that, the British Government in its Ireland Act 1949 recognized that "the Republic of Ireland had ceased to be part of His Majesty's dominions" but would not be considered a "foreign country" for legal purposes.

Ireland joined the United Nations in December 1955, after a long delay caused by the Soviet Union. After being rejected by France in 1961, Ireland finally joined the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in 1973.

Economic, Political, and Social History, 1945–Present

Ireland came out of World War II in better shape than many European countries. It had avoided direct involvement in the war and had a higher income per person than most warring nations. Ireland also received a loan of $36 million from the Marshall Plan. This money was used for housing projects and a successful effort to get rid of tuberculosis.

However, while most European countries had a strong economic boom in the 1950s, Ireland did not. Its economy grew by only 1% a year. As a result, about 50,000 people left Ireland each year during that decade. The population fell to a low of 2.81 million. The policies of protecting local industries and low public spending, which had been in place since the 1930s, were seen as failing.

Fianna Fáil's strong political control was broken in 1948–51 and 1954–1957. During these times, coalitions led by Fine Gael (descendants of Cumann na nGaedheal), along with the Labour Party, won elections and formed the government. However, these coalition governments did not change policies much. A plan by the Minister for Health, Noël Browne, to provide free medical care to mothers and children failed due to opposition from the Catholic Church and private doctors.

Poor economic growth and a lack of social services led Seán Lemass, who became leader of Fianna Fáil and Taoiseach in 1958, to say that if the economy did not improve, the future of independent Ireland was at risk.

Lemass, with T. K. Whitaker from the Department of Finance, made specific plans for economic growth. These included investing in industries, reducing protective tariffs, and giving tax breaks to foreign manufacturing companies to set up in Ireland. Attracting foreign direct investment has been a key part of Ireland's economic plan ever since. Lemass's economic plans led to 4% annual economic growth between 1959 and 1973. More government income meant more investment in social services. For example, free secondary education started in 1968. As living standards rose by 50%, fewer people left Ireland.

However, in the 1970s, the world energy crisis caused rising inflation and a budget deficit in Ireland. From 1973–1977, a coalition government tried to control spending by making cuts.

The economic crisis of the late 1970s led to a new crisis in Ireland that lasted through the 1980s. Fianna Fáil, back in power after the 1977 election, tried to boost the economy by increasing public spending. By 1981, this spending was 65% of Ireland's total economic output. Ireland's national debt grew hugely. This massive debt hurt Ireland's economy throughout the 1980s. Governments borrowed even more, and income tax rates became very high. High taxes and high unemployment caused many people to leave the country again. Governments changed frequently, with some lasting less than a year.

Starting in 1989, there were big policy changes. These included economic reforms, tax cuts, welfare reform, more competition, and a ban on borrowing for daily spending. There was also a "Social Partnership Agreement" with trade unions. Unions agreed not to strike in return for gradual pay raises. These policies were started by the 1989–1992 Fianna Fáil/Progressive Democrat government and continued by later governments. This was known as the Tallaght Strategy, where the opposition agreed not to block necessary economic measures.

The Irish economy started growing again by the 1990s, but unemployment remained high until the second half of that decade.

The Celtic Tiger

Ireland's economy had been disappointing for much of its history. But by the 1990s, it became one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. This was called the Celtic Tiger. One reason was a policy of attracting foreign investment by offering very low taxes on company profits (12%) and investing in education. This provided a well-educated workforce at relatively low wages and access to the European market. The second reason was controlling public spending through agreements with trade unions, where pay raises were given in return for no strikes. However, it was not until the second half of the 1990s that unemployment and emigration numbers improved.

By the early 2000s, Ireland had become the second richest member of the European Union (based on wealth per person). It went from receiving EU funds to contributing to them. It also changed from having more people leave to having more people move in. In 2005, its wealth per person was the second highest in the world (after Switzerland). 10 percent of the population was born abroad. The population grew to a record high of about 4.5 million.

By 2000, Ireland had a large budget surplus. The first decade of the new millennium also saw a big increase in public spending on roads, buildings, and social services. Some state-run industries, like Eircom, were also sold to private companies. In 2002, Ireland's national debt was low and continued to fall until 2007.

The Celtic Tiger started in the mid-1990s and boomed until 2001, then slowed down, only to pick up again in 2003. It slowed again in 2007. In June 2008, experts predicted Ireland would briefly go into recession before growth returned.

However, since 2001, the Irish economy had relied heavily on the property market. When this market crashed in 2008, the country's economy was badly hit.

Economic Downturn

Irish banks had invested a lot in loans to property developers. They faced ruin when the property market collapsed and loans from abroad dried up. Much of Ireland's economy and government money also depended on the property market. Its collapse, at the same time as the banking crisis, affected all parts of the Irish economy. It also meant that the money collected by the state fell sharply.

This situation worsened when the state took on the banks' debts in 2008. The Irish government, led by Brian Cowen, agreed to cover all the banks' debts. This debt, now estimated at over €50 billion, put a heavy burden on taxpayers. It also severely damaged Ireland's ability to borrow money from international markets.

The second problem was that public spending, which had risen sharply in the 2000s, was now too high to continue. The total Irish budget deficit in December 2010 was very large. Because it was unclear how much money was needed to fix the banks, international markets were unwilling to lend Ireland money at an affordable interest rate.

Under pressure from the European Union, Ireland had to accept an €85 billion loan from the IMF and EU. The interest rates were high, and the deal meant a loss of control. Irish budgets had to be approved by other EU parliaments, especially Germany's.

The political result of this crisis was the fall of the Cowen government. Fianna Fáil suffered a huge defeat in the Irish general election, 2011, winning only 17% of the vote. Many people have started leaving Ireland again, and many are worried about the economic future.

Relationship with Northern Ireland 1945–1998

The official position of the Irish state, as stated in the 1937 constitution, was that its territory included the whole island of Ireland. However, its laws only applied to the area of the Free State, as defined in the 1922 Treaty. After this, Irish governments worked for the peaceful unification of Ireland through groups like the anti-Partition League. But at the same time, the state saw paramilitary groups, especially the IRA, as a threat to its own safety. Also, their attacks on Northern Ireland could pull the Irish state into a conflict with Britain.

In the 1950s, the IRA launched attacks on security targets along the border (the Border Campaign). The Irish government first arrested the IRA's leaders and later held all IRA activists. This helped stop the campaign, and the IRA called it off in 1962. After this, the southern government under Seán Lemass tried to build closer ties with Northern Ireland authorities to promote peaceful cooperation. He and Northern premier Terence O'Neill exchanged visits, the first time leaders from both sides had done so since 1922.

However, in 1969, the Irish government faced a difficult situation when conflict erupted in Northern Ireland. This involved riots in Derry, Belfast, and other cities. The violence came from protests by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, who wanted fair treatment for Catholics and nationalists. Two events caused particular concern: the Battle of the Bogside in Derry, where nationalists fought the police for three days, and the riots in Belfast, where loyalists attacked and burned Catholic neighborhoods. Taoiseach Jack Lynch said on TV, "we can not stand by and watch innocent people being injured." This was taken to mean Irish troops might be sent over the border. This did not happen, but Irish Army field hospitals were set up, and some money and weapons were secretly given to nationalist groups for self-defense. Government ministers were later tried for allegedly supplying weapons to republican paramilitaries.

At the same time, the Provisional IRA emerged from the 1969 riots, planning an armed campaign against Northern Ireland. By 1972, their campaign was very intense. Unlike the IRA campaign of the 1950s, this one was seen as having strong public support among Northern nationalists. For this reason, Irish governments did not hold people without trial as they had before, because there was no political solution in Northern Ireland. The Irish government also refused to let British and Northern Ireland security forces chase republican paramilitaries across the border into the Republic. They arrested any soldiers or police who entered its territory armed.

However, Irish governments continued to see illegal armed activity by republicans on its territory as a major security risk. Representatives of republican paramilitaries were not allowed on television or radio.

There were also some attacks by loyalist paramilitary groups in southern Ireland, notably the Dublin and Monaghan bombings of 1975, which killed 33 people.

In 1985, the Irish government was part of the Anglo-Irish Agreement. In this agreement, the British government recognized that the Irish government had a role in a future peace settlement in Northern Ireland. In 1994, the Irish government was heavily involved in talks that led to an IRA ceasefire.

In 1998, Irish authorities were again part of a settlement, the Good Friday Agreement. This agreement set up power-sharing governments within Northern Ireland, North-South links, and connections between the UK and the Republic of Ireland. The Irish state also changed parts of its constitution to recognize Northern Ireland's existence and the desire of Irish nationalists for a united Ireland. Even after the Provisional IRA and Sinn Féin joined politics after the Good Friday Agreement, some republican paramilitary groups still want to use force to destabilize Northern Ireland. Irish security forces continue to try to prevent attacks by such groups.

Images for kids

-

U.S. president John F. Kennedy addresses the people of New Ross, 27 June 1963

-

The Spire of Dublin symbolises the modernisation and growing prosperity of Ireland.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la República de Irlanda para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la República de Irlanda para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |