Irish Boundary Commission facts for kids

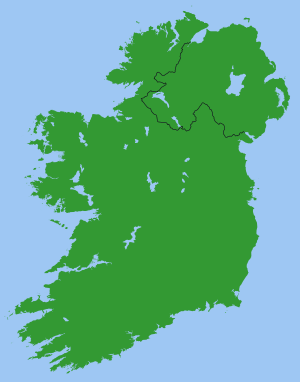

The Irish Boundary Commission (Irish: Coimisiún na Teorann) was a group that met in 1924–1925. Their job was to figure out the exact border between the Irish Free State (which is now the Republic of Ireland) and Northern Ireland.

This commission was set up because of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty. This treaty ended the Irish War of Independence. It said that if Northern Ireland decided to separate from the Irish Free State, a commission would be formed. Northern Ireland did choose to separate in December 1922, which led to the partition of Ireland (the splitting of the island).

The governments of the United Kingdom, the Irish Free State, and Northern Ireland were each supposed to pick one person for the commission. However, the Northern Ireland government refused to take part. So, the British government chose a newspaper editor from Belfast to represent Northern Ireland's interests.

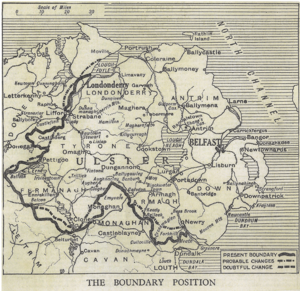

The border that existed in 1922 was set by the Government of Ireland Act 1920. Many Irish nationalists hoped the commission would give a lot of land to the Free State. They believed this because most areas along the border had more nationalists living there. But the commission suggested only small changes, and some land would even go to Northern Ireland. This information was leaked to a newspaper called The Morning Post in 1925. This leak caused protests from both unionists (who wanted to stay part of the UK) and nationalists (who wanted a united Ireland).

To avoid more arguments, the British, Free State, and Northern Ireland governments agreed to keep the commission's report a secret. On December 3, 1925, they decided to keep the existing border as it was. This agreement was signed by W. T. Cosgrave for the Free State, Sir James Craig for Northern Ireland, and Stanley Baldwin for the British government. It was part of a bigger deal that also sorted out money problems. All three parliaments then approved this agreement. The commission's full report was not made public until 1969.

Contents

How the Border Started (1920–1925)

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 was passed during the Irish War of Independence. This law divided the island into two self-governing parts of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. These parts were called Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland.

When this border was decided, the Parliament of the United Kingdom listened to the Irish Unionist Party. But they did not listen to most of the elected Irish nationalist leaders. Sinn Féin, the biggest nationalist party, refused to accept that the London Parliament had any right to decide Irish matters. They did not attend the debates.

The British government first thought about a Northern Ireland made of all nine counties of Ulster. But James Craig, the leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, clearly told the British House of Commons that six northeastern counties were the largest area unionists could realistically control. Craig suggested a Boundary Commission to check how people were spread out along the borders of these six counties. He wanted people in those areas to vote on which side they wanted to be on. However, this idea was rejected because it might cause more conflict. So, the Government of Ireland Act 1920 was passed, creating a six-county Northern Ireland using the old county borders.

The Commission's Unclear Rules

During the talks for the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George suggested a Boundary Commission. He hoped it would help solve the difficult border issue. The Irish leaders, Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, agreed to this idea, but they weren't happy about it. They thought the border would be drawn based on where people lived, down to very small areas. They believed this would give a lot of land to the Irish Free State. They hoped it would make Northern Ireland so small and weak that it wouldn't last long.

However, the final treaty also said that economic and geographical factors should be considered. Lloyd George also told James Craig that the commission would only make "small fixes" to the border, with "give and take on both sides." This meant the rules for the commission were very unclear. One expert, Kieran J Rankin, said the way the border clause was written was "only explicit in its ambiguity." Historian Jim McDermott felt that Lloyd George had tricked both Craig and Collins. Collins thought the commission would give almost half of Northern Ireland to the Free State. But Craig was told that only tiny adjustments would be made.

Article 12 of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed on December 6, 1921, described the commission like this:

...a Commission consisting of three persons, one to be appointed by the Government of the Irish Free State, one to be appointed by the Government of Northern Ireland, and one who shall be Chairman to be appointed by the British Government shall determine in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions the boundaries between Northern Ireland and the rest of Ireland, and for the purposes of the Government of Ireland Act 1920, and of this instrument, the boundary of Northern Ireland shall be such as may be determined by such Commission.

The British Parliament approved the treaty soon after, and the Irish Dáil (parliament) approved it in early 1922. In March 1922, Michael Collins and James Craig tried to solve the border issue themselves. They signed the "Craig–Collins Agreement." This agreement suggested a meeting between the Northern Ireland government and the Provisional Government of Southern Ireland. They wanted to see if they could unite Ireland, or at least agree on the border without the commission. But this agreement quickly failed for other reasons, and Michael Collins was later killed.

The Irish Free State government then set up the North-Eastern Boundary Bureau (NEBB) in October 1922. By 1925, this office had prepared many files to argue for areas of Northern Ireland to join the Free State. By December 1924, the commission's chairman had decided that public votes (plebiscites) would not be used.

The Commission's Work

A war broke out in the Irish Free State, which delayed the start of the Boundary Commission. It finally began its work in 1924. The Northern Ireland government did not want to lose any land, so they refused to appoint their own representative. To fix this, the British and Irish governments passed laws allowing the UK government to choose someone for Northern Ireland. Some people argued that the person chosen by the British government clearly supported the Unionist side.

The commission officially started on November 6, 1924, in London. Its members were:

- Justice Richard Feetham (chairman, representing the British government).

- Eoin MacNeill (Minister for Education, representing the Free State Government).

- Joseph R. Fisher (a Unionist newspaper editor, representing the Northern Ireland government, chosen by the British).

- A small team of five people helped the commission.

The commission's discussions were kept secret. On November 28, 1924, they placed an advertisement asking people and groups to send in their ideas and evidence. In mid-December, the commission toured the border area. They learned about the local conditions and met with local politicians, council members, police, and church leaders. The Catholic Church actively helped represent Catholics, with about 30 priests giving evidence. Catholic bishops told the commission that Catholics in their areas wanted to join the Free State.

The commission met again on January 29, 1925, to look at the 103 responses they received. Formal meetings were held in Ireland from March to July 1925 in places like Armagh, Enniskillen, and Derry. The commission met directly with those who had sent in their ideas. They also met with customs officials from both sides of the border and Irish Free State officials. The British and Northern Irish governments declined to attend these meetings. The commission then returned to London and continued its work through August and September 1925.

Despite what the Irish delegation wanted, Justice Feetham kept the discussions focused on a small area near the existing border. This meant there would be no large transfers of land that the Free State had hoped for. The commission's report said they started with the existing border and would only change it if there was a very good reason. They believed that "no wholesale reconstruction of the map is contemplated." They also felt that Northern Ireland "must, when the boundaries have been determined, still be recognisable as the same provincial entity."

Since Feetham ruled out public votes, the commission mostly used information about religious groups from the 1911 United Kingdom census. They also used the information gathered from the meetings in 1925.

A draft of the new border was decided on October 17, 1925. The new border was only slightly different from the old one. It was shorter, going from 280 miles to 219 miles. Only small amounts of land were transferred to the Free State (282 square miles), and some land even went the other way (78 square miles). In total, 31,319 people would have moved to the Irish Free State (mostly Catholics), and 7,594 people would have moved to Northern Ireland (mostly Protestants). Only about one in every twenty-five Northern Irish Catholics would have ended up under Free State rule. By November 5, the commission agreed their work was done and they were ready to give their suggestions to the British and Irish governments.

Areas Considered and Changes Suggested

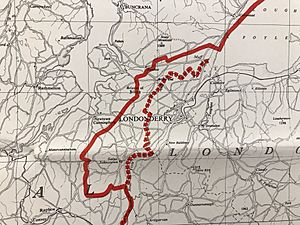

Derry and Parts of County Donegal

The future of Derry city, its nearby areas, and the Protestant parts of County Donegal was a big debate. Many groups spoke to the commission. Nationalists in Derry and Donegal wanted Derry city to join the Irish Free State. If not, they wanted the border to follow the River Foyle, leaving most of the city in the Free State.

However, Derry's city council and port officials wanted only small changes to the border that would help Northern Ireland. Shirt and collar makers wanted the border to stay the same. They said their business relied on easy access to the British market.

For Donegal, Protestants wanted the whole county to be part of Northern Ireland. They said it had many Protestants and was closely linked to County Londonderry. Both Nationalists and Unionists agreed that County Donegal depended on Derry as its main town. They said the customs border between them hurt trade. Unionists argued this meant Donegal should be in Northern Ireland, while Nationalists said it meant Derry should be in the Free State.

The commission decided against moving Derry to the Free State. Even though it had a Catholic majority (54.9%), they felt this wasn't enough for such a big change. They also thought moving Derry would create new problems between Derry and the rest of County Londonderry, and counties Tyrone and Fermanagh. They believed Derry's industries would suffer if cut off from their English markets. The idea of drawing the border along the River Foyle was also rejected because it would split the town.

However, the commission did suggest that mostly Protestant areas in County Donegal near the border should join Northern Ireland. This was based on their Protestant population and would move the customs border further out, helping local traders. If these changes had happened, the Donegal towns of Muff, Killea, Carrigans, Bridgend and St Johnston would have moved to Northern Ireland.

Unionists also argued that all of Lough Foyle should be part of County Londonderry. The Free State disagreed, and the British government didn't take a side. The commission couldn't find clear evidence either way. In the end, they suggested the border follow the main shipping channel through the lough.

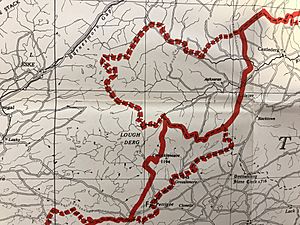

County Tyrone

In County Tyrone, Catholics and Protestants lived mixed together, making it hard to draw a fair border. Nationalist groups wanted the whole county to join the Irish Free State because most people there were Catholic. This was supported by officials from Omagh and other towns.

However, the Tyrone Boundary Defence Association (TBDA) disagreed. They said many areas, especially near the border, had a Protestant majority. Unionist groups from towns like Clogher and Dungannon supported this.

The commission found that areas right next to the border were mostly Protestant. The main exception was Strabane, which had more Catholics. But the areas east of Strabane, which relied on it for business, were mostly Protestant. It was also thought impossible to move Strabane to the Free State without causing major economic problems. The commission also noted that Tyrone's economy depended on other parts of Northern Ireland. Much of western Tyrone traded with Derry, and eastern Tyrone traded with Belfast and Newry. Also, if Tyrone joined the Free State, County Fermanagh (which had many Protestants) would likely have to join too, making Northern Ireland much smaller. In the end, only Killeter and a small rural area west of it, plus a tiny area northeast of Castlederg, were suggested to move to the Irish Free State.

County Fermanagh

The commission heard from Nationalist groups in County Fermanagh. They also heard from the Fermanagh County Council, which was mostly Unionist. The Nationalist groups argued that since the county had a Catholic majority, it should fully join the Free State. They also said the county's economy was too connected to the Free State counties around it to be separated. The county council disagreed. They wanted small changes to the border that would benefit Northern Ireland, like moving Pettigo (in County Donegal) and the Drummully area (in County Monaghan) into Northern Ireland.

The commission concluded that the existing border negatively affected towns like Pettigo (in County Donegal) and Clones (in County Monaghan). The commission suggested several border changes:

- The rural part of County Donegal between counties Tyrone and Fermanagh (including Pettigo) would move to Northern Ireland.

- The Free State would gain a large part of southwest Fermanagh (including Belleek, Belcoo, Garrison and Larkhill).

- A piece of land in southern Fermanagh would go to the Free State.

- The areas around the Drummully area would go to the Free State (except a tiny sliver of northwestern Drummully, which would go to Northern Ireland).

- Rosslea and its surrounding area would also go to the Free State.

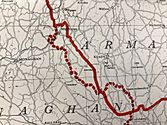

Counties Armagh and Down, with Parts of County Monaghan

Nationalist residents wanted areas like Middletown, Keady, Armagh, Newry, South Armagh, and southern County Down (including Warrenpoint and Kilkeel) to join the Free State. Unionists in these areas, along with business groups, opposed these claims. They argued that Newry, Armagh, and other areas were too connected economically to the rest of Northern Ireland to be moved. Protestant residents of Mullyash, County Monaghan, wanted to join Northern Ireland.

The commission suggested transferring a thin strip of land including Derrynoose, Tynan, and Middletown to the Free State. They also recommended moving all of South Armagh (including towns like Cullyhanna, Crossmaglen, and Forkhill) to the Free State. This was based on their Catholic majorities and the fact that these areas did not rely economically on Newry or the rest of Armagh. The Mullyash area of County Monaghan was to be transferred to Northern Ireland. Other areas were too mixed to divide fairly. Newry, which had a Catholic majority, was kept in Northern Ireland because moving it would cause "economic disaster." Because of Newry's location, no serious transfers from County Down to the Free State were considered.

The Report is Leaked

On November 7, 1925, an English newspaper called The Morning Post published secret notes from the commission's talks. It even included a draft map. People believe the information came from Fisher, who had been telling Unionist politicians about the secret work. The leaked report correctly showed that parts of eastern County Donegal would move to Northern Ireland.

The commission's suggestions, as reported in The Morning Post, were embarrassing for Dublin. They felt this went against the main goal of the commission, which they thought was to give more Nationalist parts of Northern Ireland to the Free State. MacNeill left the commission on November 20 and resigned from his government job on November 24. Even though he left, MacNeill later voted for the final agreement on December 10.

Agreement Between Governments (November–December 1925)

The newspaper leak effectively stopped the commission's work. After MacNeill resigned, Fisher and Feetham continued without him. Since the commission's official report would have immediate legal effects, the Free State government quickly started talks with the British and Northern Ireland governments.

In late November, Irish government members visited London. The Irish believed that Article 12 of the treaty only meant that areas *within* Northern Ireland could be given to the Free State. But the British insisted that the entire 1920 border could be changed in either direction.

Cosgrave worried his government might fall. But after getting an idea from a senior civil servant, Joe Brennan, he thought of a bigger solution. This solution would also include financial matters between the countries. On December 2, Cosgrave explained his view of the problem to the British Cabinet.

Under Article 5 of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, the Irish Free State had agreed to pay its share of the British Empire's debt. The British claimed this was £157 million.

(5) The Irish Free State shall assume liability for the service of the Public Debt of the United Kingdom as existing at the date hereof and towards the payment of war pensions as existing at that date in such proportion as may be fair and equitable, having regard to any just claims on the part of Ireland by way of set-off or counter-claim, the amount of such sums being determined in default of agreement by the arbitration of one or more independent persons being citizens of the British Empire.

This payment had not been made by 1925, partly because of the high costs from the Irish Civil War (1922–1923). The main part of the new agreement was that the 1920 border would stay the same. In return, the UK would not demand the debt payment agreed in the treaty. Since 1925, this payment was never made or asked for. However, the Free State did have to pay costs related to the Irish War of Independence, which the British called 'malicious damage'.

Historian Diarmaid Ferriter (2004) suggested a more complex trade-off. The Free State was freed from its debt, and the report was not published. In return, the Free State gave up its claim to rule some Catholic/Nationalist areas of Northern Ireland. This way, each side could blame the other for the outcome. W. T. Cosgrave admitted that the safety of the Catholic minority depended on the good intentions of their neighbors. Economist John Fitzgerald (2017) argued that getting rid of the UK debt was a big relief for the Free State. It helped Ireland become more independent, as its debt-to-GNP (how much it owed compared to its economy) dropped from 90% to 10%.

The final agreement between the Irish Free State, Northern Ireland, and the United Kingdom was signed on December 3, 1925. Later that day, Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin read the agreement in the House of Commons. The agreement became law through the "Ireland (Confirmation of Agreement) Act," which the British parliament passed unanimously on December 8–9. The three governments made the agreement, and the commission then simply approved it. So, whether the commission's report was published or not became unimportant. The agreement was officially registered with the League of Nations on February 8, 1926.

Discussions in the Irish Parliament (December 1925)

In the Dáil (Irish parliament) discussions on December 7, 1925, Cosgrave said the exact amount of the Imperial debt was not set. But it was estimated at £5–19 million annually. The UK's total debt was over £7 billion. The Free State's annual budget was about £25 million. Cosgrave's goal was to get rid of this debt: "I had only one figure in my mind and that was a huge nought. That was the figure I strove to get, and I got it." Cosgrave also hoped that the large nationalist minority in Northern Ireland would help bring Belfast and Dublin closer.

On the last day of the debate, Cosgrave said that one reason for independence, ending poverty caused by London's high taxes on Ireland, had not been solved even after four years of freedom:

In our negotiations we went on one issue alone, and that was our ability to pay. Not a single penny of a counter-claim did we put up. We cited the condition of affairs in this country—250,000 occupiers of uneconomic holdings, the holdings of such a valuation as did not permit of a decent livelihood for the owners; 212,000 labourers, with a maximum rate of wages of 26s. a week: with our railways in a bad condition, with our Old Age Pensions on an average, I suppose, of 1s. 6d. a week less than is paid in England or in Northern Ireland, with our inability to fund the Unemployment Fund, with a tax on beer of 20s. a barrel more than they, with a heavier postage rate. That was our case.

His main opponent was William Magennis, a Nationalist politician from Northern Ireland. He was especially upset that the Council of Ireland was not mentioned. This council was a way for future unity, as suggested in the Government of Ireland Act 1920.

Magennis argued that the 1920 Act had a plan for eventual unity. He asked if the new agreement had any plan for setting up a parliament for all of Ireland. He said, "No!"

The government side felt that some kind of border, and the division of Ireland, had been likely for years. If the border moved closer to Belfast, it would be harder to get rid of in the long run. Kevin O'Higgins wondered if the Boundary Commission was truly a good idea. He questioned if moving the line a few miles, leaving Nationalists north of it in an even smaller group, would make unity less likely.

On December 9, a group of Irish nationalists from Northern Ireland came to share their views with the Dáil, but they were turned away.

After four days of intense debate, the boundary agreement was approved on December 10 by a Dáil vote of 71 to 20. On December 16, the Irish Senate approved it by 27 votes to 19.

Why the Report Was Not Published

Both the Irish President of the Executive Council and the Northern Ireland Prime Minister agreed during the talks on December 3 to keep the report secret. This was part of the larger agreement between the governments. The remaining commissioners discussed this with the politicians and expected the report to be published within weeks.

However, W. T. Cosgrave said he:

...believed that it would be in the interests of Irish peace that the Report should be burned or buried, because another set of circumstances had arrived, and a bigger settlement had been reached beyond any that the Award of the Commission could achieve.

Sir James Craig added that:

If the settlement succeeded it would be a great disservice to Ireland, North and South, to have a map produced showing what would have been the position of the persons on the Border had the Award been made. If the settlement came off and nothing was published, no-one would know what would have been his fate. He himself had not seen the map of the proposed new Boundary. When he returned home he would be questioned on the subject and he preferred to be able to say that he did not know the terms of the proposed Award. He was certain that it would be better that no-one should ever know accurately what their position would have been.

For different reasons, the British government and the two remaining commissioners agreed with these views. The commission's full report was not published until 1969. Even the discussions about keeping the report secret remained hidden for decades.

Images for kids

See also

- History of Ireland

- History of Northern Ireland

- History of the Republic of Ireland

- Repartition of Ireland

- Government of Ireland Bill 1886 (First Irish Home Rule Bill)

- Government of Ireland Bill 1893 (Second Irish Home Rule Bill)

- Government of Ireland Act 1914 (Third Irish Home Rule Bill)

- Government of Ireland Act 1920 (Fourth Irish Home Rule Bill)

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |