Brexit withdrawal agreement facts for kids

| Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community | |

|---|---|

United Kingdom (UK) European Union (EU) and Euratom

|

|

| Type | Treaty setting out terms of withdrawal |

| Context | UK withdrawal from the EU (Brexit) |

| Drafted | November 2018 October 2019 (revision) |

| Signed | 24 January 2020 |

| Effective | 1 February 2020 |

| Condition | Ratification by the European Union (Council of the European Union after consent of the European Parliament), Euratom (Council of the European Union) and the United Kingdom (Parliament of the United Kingdom). |

| Negotiators |

|

| Signatories | Boris Johnson for the UK Ursula von der Leyen and Charles Michel for the EU and Euratom |

| Parties | |

| Depositary | Secretary General of the Council of the European Union |

| Languages | The 24 EU languages |

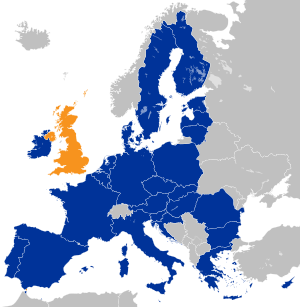

The Brexit withdrawal agreement is an important treaty between the European Union (EU), Euratom (a European group for nuclear energy), and the United Kingdom (UK). It was signed on 24 January 2020. This agreement set the rules for the UK leaving the EU and Euratom.

The main text of the treaty was released on 17 October 2019. It was a new version of an earlier agreement from November 2018. The first version was rejected three times by the House of Commons, which is part of the UK Parliament. This led to Theresa May stepping down as Prime Minister. Boris Johnson then became the new Prime Minister on 24 July 2019.

The Parliament of the United Kingdom approved the agreement on 23 January 2020. The UK government officially confirmed its approval on 29 January 2020. The Council of the European Union approved it on 30 January 2020, after the European Parliament agreed on 29 January 2020. The UK officially left the EU at 11 p.m. GMT on 31 January 2020. At that exact moment, the Withdrawal Agreement became law.

This agreement covers important topics like money, the rights of citizens, border rules, and how to solve disagreements. It also included a transition period and a general idea of the future relationship between the UK and the EU. The agreement was first put forward on 14 November 2018. It was the result of long Brexit negotiations. Leaders from the 27 remaining EU countries and the British Government (led by Prime Minister Theresa May) supported it. However, it faced strong opposition in the British Parliament, which needed to approve it. The European Parliament also needed to give its approval.

On 15 January 2019, the House of Commons voted against the agreement. They rejected it again on 12 March 2019, and a third time on 29 March 2019. On 22 October 2019, the updated agreement, negotiated by Boris Johnson's government, passed an early stage in Parliament. But Johnson stopped the process when his plan for quick approval failed. He then announced a general election. On 23 January 2020, Parliament finally approved the agreement by passing the Withdrawal Agreement Act. The European Parliament gave its consent on 29 January 2020. The Council of the European Union then officially approved it on 30 January 2020.

The agreement included a transition period. This period lasted until 1 January 2021. During this time, the UK stayed in the single market. This helped to keep trade smooth while a long-term relationship was being worked out. If no new agreement was made by this date, the UK would have left the single market without a trade deal. A separate, non-binding statement about the future EU–UK relationship was also connected to the agreement.

Why the Agreement Was Needed

The 2016 Brexit Referendum

In 2015, the Conservative Party promised a public vote on whether the UK should stay in the EU. This promise was part of their plan for the general election.

The vote, called a referendum, happened on 23 June 2016. The result was that 51.9% of people voted to leave the European Union, and 48.1% voted to stay.

What the 2018 Draft Agreement Covered

The first version of the withdrawal agreement in 2018 was very long. It covered several key areas:

- Money: How money, assets, and debts would be shared.

- Citizens' Rights: The rights of British citizens living in EU countries and EU citizens living in the UK.

- Borders and Customs: Especially for the border between the UK and the Republic of Ireland.

- Laws and Disputes: How laws would apply and how disagreements would be settled.

This draft also set up a transition period until 31 December 2020. This period could be extended if both sides agreed. During this time, EU laws still applied to the UK. The UK also continued to pay into the EU budget. However, the UK did not have a say in EU decisions. This transition period gave businesses time to get ready for the changes. It also gave the UK and EU governments time to negotiate a new trade deal.

For the Irish border question, a special plan called the Irish backstop was added. This was a safety net to avoid a hard border (where goods and people are strictly checked) if no other solution was found. It meant the UK would follow some EU customs rules, and Northern Ireland would keep some single market rules.

The agreement also planned for a Joint Committee. This committee would have representatives from both the EU and the UK government. It would oversee how the agreement was put into action.

Main Parts of the 2018 Draft

The agreement had important sections:

- Common Rules: This part explained how the UK would leave the EU and Euratom. It also defined the UK's territory and made sure the agreement was legally binding. It stated that after the transition, the UK would lose access to EU information systems.

- Citizens' Rights: This section defined who counted as a citizen, family member, or border worker. It ensured that people could continue to live in their host country. It also said that people could not be treated unfairly because of their nationality.

- Rights and Obligations: British and EU citizens, along with their family members, kept the right to live in their host country. Host countries could not limit these rights. People with valid documents would not need visas to enter or leave. If a visa was needed for family members joining later, it would be given quickly and for free. This part also covered rights for workers and self-employed people, and how professional qualifications would be recognized.

- Social Security: This part dealt with how social security systems would work together.

- Goods on the Market: It stated that goods or services legally sold before the UK left the EU could still be sold in the UK or EU countries.

- Customs Procedures: This section covered customs checks for goods moving between the UK and the EU.

- VAT and Excise Duty: This part explained how Value Added Tax (VAT) would apply to goods traded between the UK and the EU.

Annexes and the Northern Ireland Backstop

The 2018 draft had ten extra parts called annexes. The first one was a plan to keep an open border on the island of Ireland. This was known as the 'Irish backstop'. It was a safety plan to avoid a hard border if no other solution was found.

This backstop caused many problems for the UK government, especially with the Democratic Unionist Party, which supported the government. This draft was later replaced by a new Northern Ireland Protocol in 2019.

Changes Made in 2019

The agreement was changed in 2019 under Boris Johnson's government. About 5% of the text was updated.

New Protocols

The agreement also included special rules for the 'Sovereign Base Areas in Cyprus' and Gibraltar.

Northern Ireland Protocol

The original Irish backstop was removed. It was replaced by a new protocol for Northern Ireland and Ireland. This new plan meant that Great Britain could fully leave the European Single Market and the EU Customs Union. However, Northern Ireland would still follow some EU customs rules. A key difference was that the Northern Ireland Assembly would get to vote every four years on whether to continue with these arrangements.

This new protocol still kept some EU laws for goods and electricity in Northern Ireland. It also gave the European Court of Justice a role in making sure rules were followed.

Political Declaration

The 2019 changes also updated the political declaration. This declaration talks about the future relationship between the UK and the EU. Some words were changed, which meant that certain standards, like labour standards, might not be covered by dispute resolution. Also, the idea of a "level playing field" (fair competition rules) was moved from the legally binding agreement to this political declaration.

Joint Committee of the Withdrawal Agreement

The agreement created a Joint Committee. This committee helps to put the agreement into practice. It is led by both the EU and the UK and has six smaller committees. This committee is important for managing any problems or disagreements.

Both sides have equal say, and if they can't agree, they can go to an international arbitration panel. One of the smaller committees, the 'Northern Ireland subcommittee', has received a lot of attention because of issues related to the Irish Sea border.

The Joint Committee has met nine times as of February 2022.

Specialised Committee on Citizens' Rights

This committee was set up to check how the rules about citizens' rights are being followed. It has met ten times as of June 2022.

UK Parliament Votes

On 15 January 2019, the House of Commons voted against the Brexit withdrawal agreement by a large number of votes. This was the biggest defeat for a UK government in history. The government survived a vote of confidence the next day. On 12 March 2019, the Commons voted against the agreement a second time.

A third vote was planned for 19 March 2019, but the Speaker of the House of Commons stopped it. This was based on an old rule that prevents the government from making Parliament vote repeatedly on the same issue. However, a shorter version of the agreement, without the political declaration, was allowed. So, a third vote happened on 29 March 2019, but it was also rejected.

On 22 October 2019, the House of Commons agreed to the updated agreement (negotiated by Boris Johnson). But when Johnson's plan for a quick approval failed, he paused the process.

After the Conservative Party won the 2019 United Kingdom general election in December 2019, the House of Commons passed the Withdrawal Agreement Bill. After some changes suggested by the House of Lords, the bill became law on 23 January 2020. This allowed the UK to officially approve the agreement.

European Union Approval

The European Parliament also approved the agreement on 29 January 2020. The Council of the European Union officially approved it on 30 January 2020. On the same day, the EU formally confirmed its approval. This meant the deal was complete and could become law when the UK left the EU at 11 p.m. GMT on 31 January 2020.

Future Relationship Plan

The Declaration on Future European Union–United Kingdom Relations is a statement that was agreed alongside the main Withdrawal Agreement. It is not legally binding, but it outlines the planned future relationship between the UK and the EU after Brexit and the end of the transition period.

How the Agreement Was Put into Practice

Citizens' Rights

In June 2020, a group called "British in Europe" said that many EU countries had not yet set up systems to confirm the future rights of British citizens living there. They said that about 1.2 million British citizens were unsure about their future. In contrast, the UK had launched its own system for EU citizens in March 2020. More than 3.3 million people had been given "pre-settled" or "settled" status to stay in the UK after Brexit.

Brexit also meant that British residents living in EU countries lost the right to vote in European Parliament elections and the right to work in other EU countries.

Northern Ireland

In September 2020, there were reports that the British government planned new laws that would go around the Northern Ireland Protocol in the withdrawal agreement. The government said these laws would clarify parts of the protocol. However, EU leaders warned the UK not to break international law. On 8 September, a UK minister stated that the planned law would "break international law".

On 1 October 2020, the European Commission started a legal process against the UK. They said the UK's planned law was "in full contradiction" to the Northern Ireland Protocol. After discussions, the UK agreed to remove the problematic parts of its law.

However, on 3 March 2021, the UK government announced it would extend a grace period for checks on some goods entering Northern Ireland from Great Britain. The EU objected to this, saying it was the second time the UK tried to break international law regarding the protocol. The European Parliament, which still needed to officially approve the agreement, delayed its decision until the issue was resolved.

The Windsor Framework, announced in February 2023, changed parts of the Protocol. It aimed to make customs checks easier for goods coming from Great Britain. It also gave the UK government more control over VAT rates in Northern Ireland. Medicines in Northern Ireland would be regulated by the UK, not the EU. This framework also gave Northern Ireland and the UK government a way to object to new EU laws that might affect them.

See also

- European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) – a separate group from the EU, but with the same members, which the UK also left

- EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement

- No-deal Brexit

- Proposed referendum on the Brexit withdrawal agreement

- Trade negotiation between the UK and the EU