Shangani Patrol facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Shangani Patrol |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Matabele War | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Matabele Kingdom | British South Africa Company | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~3,000 | 37 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~400–500 killed | 34 killed | ||||||

The Shangani Patrol was a small group of 34 soldiers from the British South Africa Company. In 1893, during the First Matabele War, they were surrounded and defeated by over 3,000 Matabele warriors. This happened north of the Shangani River in what is now Zimbabwe.

Led by Major Allan Wilson, the patrol's brave final stand became a famous story in British and Rhodesian history. It's often compared to other famous last stands like the Battle of the Little Bighorn or the Battle of the Alamo in the United States.

The patrol was part of a larger group trying to capture the Matabele King Lobengula. They crossed the Shangani River on 3 December 1893. The next morning, they found Lobengula's wagon but were ambushed by many Matabele fighters. Outnumbered, the patrol fought bravely. Three men managed to escape to get help, but the river had flooded, and the main British force was also in a fight. Wilson and his men were left alone. They fought until they ran out of bullets, killing many Matabele warriors before they were all defeated.

After their deaths, the patrol members, especially Wilson and Captain Henry Borrow, became national heroes. They were seen as symbols of courage against impossible odds. The date of the battle, 4 December 1893, became a public holiday in Rhodesia for many years. A film about the event, Shangani Patrol, was made in 1970.

Contents

Why the Shangani Patrol Happened

The Scramble for Africa and British Ambitions

During the 1880s, European countries were trying to take control of parts of Africa. This was called the "Scramble for Africa". A British businessman named Cecil Rhodes had a big dream. He wanted to connect the British territories from the Cape of Good Hope (in South Africa) all the way to Cairo (in Egypt) with a railway. This idea was known as the "Cape to Cairo red line".

To do this, Rhodes needed to control the land between these two points. North of the British Cape Colony were independent states, including the Matabele Kingdom led by King Lobengula.

The British South Africa Company

In 1888, Rhodes got mining rights from King Lobengula. Then, in 1889, Queen Victoria gave Rhodes and his British South Africa Company a special permission called a "royal charter". This charter allowed the company to trade, own land, create banks, and even have its own police force. This police force was first called the British South Africa Company's Police, and later the Mashonaland Mounted Police.

The company promised to govern and develop the land they took over. They also said they would respect local laws and allow free trade. The first settlers called their new home "Rhodesia" after Cecil Rhodes.

Rising Tensions and War

However, the company often ignored or twisted agreements with Lobengula and other local leaders, especially about mining rights. The company also told Lobengula to stop his traditional raids on the Mashona people, who lived in areas controlled by the white settlers.

Lobengula was angry about the company's actions. In 1893, he decided to fight back. Matabele warriors began attacking Mashona people near Fort Victoria. A meeting to stop the fighting ended in violence. This marked the start of the First Matabele War.

Early Battles and Lobengula's Retreat

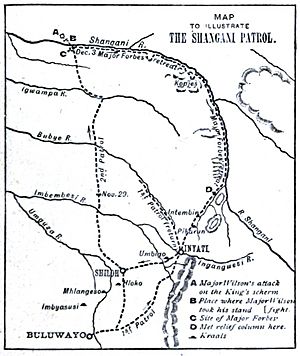

British South Africa Company soldiers marched from Fort Salisbury and Fort Victoria. They met up on 16 October 1893, forming a force of about 700 men. This group was led by Major Patrick Forbes and had five powerful Maxim machine guns.

Forbes's column moved towards Lobengula's capital city, Bulawayo. The Matabele army tried to stop them. On 25 October, 3,500 Matabele warriors attacked near the Shangani River. The Matabele were strong fighters, but the Maxim guns were incredibly powerful. An eyewitness said the guns "mowed them down literally like grass". About 1,500 Matabele were killed, while the company lost only four men.

A week later, on 1 November, 2,000 Matabele riflemen and 4,000 warriors attacked Forbes again at Bembezi. Again, the Maxim guns were too strong. About 2,500 more Matabele were killed.

When Lobengula heard about the defeat at Bembezi, he fled Bulawayo. On 3 November 1893, he and his people burned their royal town as they left. The company soldiers entered the burning city the next day. They put out the fires and began rebuilding Bulawayo as a new white-run city.

The Chase for King Lobengula

Forbes's Pursuit

After taking Bulawayo, the British South Africa Company wanted to capture King Lobengula. Major Forbes led a group of about 470 men to find him. Lobengula was heading north in his wagon, leaving clear tracks. Forbes's men followed closely, finding recently left Matabele camps.

Heavy rain slowed both the king and his pursuers. Forbes decided to split his force, moving ahead with a smaller, faster group of 160 men. On 3 December 1893, he reached the southern bank of the Shangani River. He saw Matabele warriors and cattle crossing the river, showing that the king had just passed.

Forbes sent Major Allan Wilson with 12 men and eight officers to scout ahead across the river. He told Wilson to return by nightfall.

Wilson's Patrol Stays Out

Meanwhile, Forbes set up a defensive camp (called a laager) near the southern bank. He learned from a captured Matabele man that the king was indeed where Wilson had gone. The prisoner said Lobengula was ill and had about 3,000 warriors with him. These warriors were demoralized but determined to protect their king.

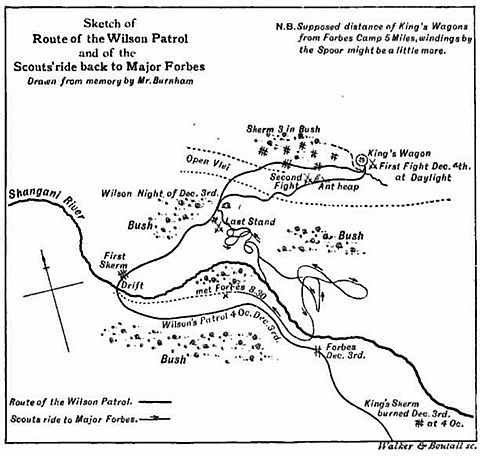

Wilson's men stayed north of the river much longer than expected. They had not returned when darkness fell. Around 9:00 PM, two of Wilson's men arrived at Forbes's camp. They reported that Wilson had found Lobengula's tracks and followed him for about 8 kilometres. Wilson believed he had a good chance of capturing the king alive and planned to stay north of the river overnight. He asked Forbes to send more men and a Maxim gun in the morning.

Reinforcements Arrive

Wilson's patrol continued to move closer to Lobengula's camp. Captain William Napier called out to the king in the Matabele language, but there was no reply. The Matabele leaders stayed hidden, confused by the small number of Company soldiers. They thought it might be a trap.

Wilson sent another message to Forbes around 11:00 PM, repeating that he would stay near the king overnight. He asked Forbes to bring the entire column across the river by 4:00 AM. Forbes thought it was too risky to cross the river at night, fearing his force could be surrounded. But he also knew that calling Wilson back would mean losing Lobengula.

As a compromise, Forbes sent Captain Henry Borrow with 21 men across the river at 1:00 AM on 4 December. Borrow was told to tell Wilson that Forbes's camp was surrounded and expected an attack. When Borrow's men arrived, Wilson and his officers were not happy. There were fewer men than expected, and no Maxim gun. Only 20 of the reinforcements reached Wilson, bringing the patrol's total to 37 men.

The Battle: Wilson's Last Stand

Ambush on Both Sides

Wilson talked with his officers. No one felt very hopeful. One officer said, "This is the end." Despite the danger, Wilson decided to push forward: "Let's ride on Lobengula," he said. Some historians believe this was a very risky choice.

The 37 men moved towards Lobengula's camp. The king's wagon was still there, but he was gone. Suddenly, the soldiers heard rifles being prepared in the woods around them. A Matabele leader stepped out and announced that thousands of Matabele surrounded them. He then fired his rifle, signaling the attack.

A volley of shots came from the Matabele riflemen, but most went too high. Only two of the patrol's horses were hit. Wilson immediately ordered his men to fall back to a thick wood for cover. Three men were wounded during this retreat.

Meanwhile, Forbes heard the shots from across the river and moved towards the southern bank to help Wilson. But Forbes's column was also ambushed by Matabele hidden in the bushes. Five Company soldiers were injured. This fight lasted about an hour. During this time, heavy rains upstream caused the Shangani River to flood badly.

A Desperate Breakout Attempt

Wilson led his men back towards the river, hoping to rejoin Forbes. They moved for about 1.6 kilometres but saw a line of Matabele warriors blocking their way. Wilson refused to leave his wounded men behind. In a desperate move, he sent three of his men—American scouts Frederick Russell Burnham and Pearl "Pete" Ingram, and Australian Trooper William Gooding—to break through the Matabele line, cross the river, and bring back help. Wilson, Borrow, and the rest prepared for a final stand.

Burnham, Ingram, and Gooding managed to get through the Matabele line. The Matabele then closed in on the surrounded patrol, firing from cover and killing several men. After a while, the Matabele leader ordered his men to charge and finish them off. But the Matabele soon pulled back, having lost about 40 men.

Burnham, Ingram, and Gooding reached the Shangani River around 8:00 AM. They saw that the river was now too high for Forbes to cross and help. Realizing they couldn't get help for Wilson, they decided to rejoin Forbes. They crossed the swollen river with great difficulty and rode to where the battle was still going on. Burnham told Forbes, "I think I may say that we are the sole survivors of that party."

The Final Moments

What happened next to the Shangani Patrol is known only from Matabele accounts. These stories were gathered over many years. According to these accounts, the Matabele warriors offered the remaining white soldiers their lives if they surrendered, but Wilson's men refused.

They used their dead horses for cover and fought bravely, killing many more Matabele warriors (estimated around 500). But the overwhelming Matabele force slowly closed in from all sides. The Company soldiers kept fighting even when badly wounded, which amazed the Matabele. One Matabele leader said, "These are not men but magicians."

Late in the afternoon, after hours of fighting, Wilson's men ran out of ammunition. They stood up, shook hands, and sang a song, possibly "God Save the Queen". The Matabele then put down their rifles and charged with assegai spears. According to one Matabele eyewitness, "the white inDuna" (Wilson) was the last to die. He stood still, bleeding from many wounds, until a young warrior killed him with a spear.

The Matabele leader Mjaan ordered that the bodies of the patrol be left untouched. However, the next morning, the whites' clothes and two of their facial skins were collected to show Lobengula proof of the battle's outcome. A Matabele warrior later said, "The amakiwa [whites] were brave men; they were warriors."

Who Were the Shangani Patrol Men?

The Shangani Patrol started with 43 men, including Major Wilson. When the battle began, 37 were present. This number dropped to 34 when Wilson sent Burnham, Ingram, and Gooding to get help. All the men left behind were killed in action.

These soldiers came from different parts of the British Empire and other countries. Most were born in Britain. Major Wilson was Scottish, and Captain Borrow was from Cornwall. Other members came from South Africa, the United States (Burnham and Ingram), India, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Aftermath of the Battle

Forbes's Retreat and Lobengula's Death

After the battle on the southern side of the Shangani, Forbes and his column searched for survivors from Wilson's group. But they couldn't cross the flooded river and saw no signs of life. They correctly guessed that all the men across the river had been killed. They then began a difficult journey back to Bulawayo, with very little food and constant attacks from Matabele raiding parties.

The retreat lasted two weeks. In pouring rain, the soldiers were often on foot, eating horse meat, and wearing makeshift shoes. Forbes felt so ashamed that he let Commandant Piet Raaff take charge of leading the column back. Raaff used his experience to help the tired men survive. He avoided several Matabele ambushes and even set up a fake camp that the Matabele attacked for half a day, wasting their ammunition.

When Forbes's column finally returned to Bulawayo on 18 December 1893, he was met with quiet disapproval. Cecil Rhodes, the Company chief, walked past Forbes without a word. Raaff, however, was publicly praised by Rhodes for bringing the column back safely.

Meanwhile, King Lobengula moved further north-east, away from the company's reach. However, his sickness, which was smallpox, got much worse and he died on 22 or 23 January 1894. With the king dead, Mjaan, the most senior Matabele leader, took command. Mjaan's only son had been killed in the war, and he wanted peace.

In late February 1894, Mjaan and other Matabele leaders met with James Dawson, a trader they knew well. Dawson offered peace on behalf of the company. The Matabele leaders agreed. They also told Dawson what had happened to the Shangani Patrol. They led him to the battle site, where he saw the bodies of the soldiers, which were mostly skeletons. Dawson was the first non-Matabele to learn the full story of the last stand.

Remembering the Shangani Patrol

News of the patrol's fate spread quickly across the British Empire and the world. Newspapers wrote a lot about the battle, calling it a "massacre" and printing stories about Wilson and the other soldiers. Pictures showing the final fight were also published.

The Shangani Patrol became a very important part of Rhodesian identity. Wilson and Borrow were seen as heroes who showed courage against impossible odds. Their last stand became a kind of national legend, similar to the Alamo or Custer's Last Stand in America. In 1895, 4 December was made "Shangani Day", an annual public holiday in Rhodesia.

The bodies of the patrol members were first buried on the battlefield by James Dawson. He carved a cross and the words "To Brave Men" into a Mopane tree there. Later, in 1904, Cecil Rhodes had the patrol's remains reburied next to him at World's View in the Matopos Hills.

A memorial called the Shangani Memorial was also built at World's View in July 1904. It's a tall, granite structure with bronze panels showing members of the patrol. The main inscription reads, "To Brave Men," with a smaller dedication: "To the enduring memory of Allan Wilson and his men whose names are hereon inscribed and who fell in fight against the Matabele on the Shangani River on December the 4th. 1893. There was no survivor."

Legacy and Remembrance

The story of the Shangani Patrol's last stand was even re-enacted at an exhibition in London in 1899. This show, called Savage South Africa, included scenes from the Matabele wars and ended with "Major Wilson's Last Stand." A short film based on this show was also released in 1899. Later, a historical war film called Shangani Patrol was made in 1970.

Today, much of the old heroic stories about the patrol have changed since the country became Zimbabwe in 1980. However, World's View remains a popular tourist attraction. In the 1990s, there was a campaign to remove the monument and graves, but it faced strong opposition. People wanted to keep the site because of the visitors it brings and out of respect for its history.

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |